- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Author: Elena Cué

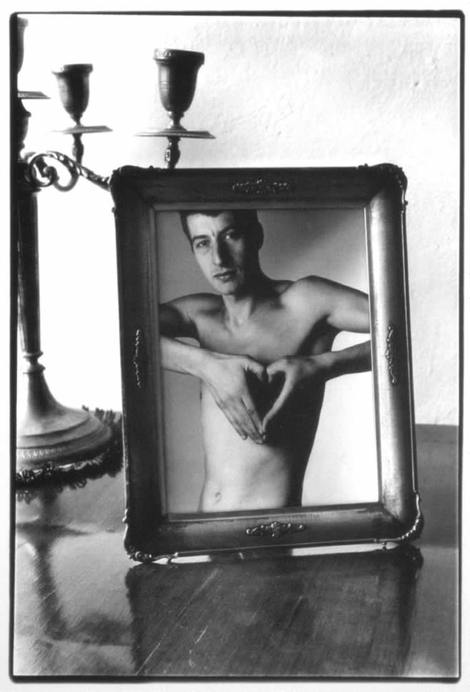

Maurizio Cattelan was born in Padua, Italy in 1960. Internationally, he is considered as the most relevant Italian artist in the contemporary art world. As a self-taught artist, his career began in 1989 with a black and white photograph titled Family Syntax; a framed self-portrait in which he appears forming a heart with his hands over his naked chest. He has previously collaborated with a gallery in Milan working on furniture design.

Elena Cué: Your work is anarchic, irreverent, absurd and provocative to the extreme. It is often a dramatic satirical representation. One could say he is post-Dada who questions all established values; religious authority, our society, materialism and contemporary art itself. His attitude towards established authority, and thus towards its political and religious representatives comes from his school days. His work is cast as a dark comedy so that each individual may develop their own interpretation.

Do you approach your own existence with the same sense of humor?

Maurizio Cattelan: I think humor and irony include tragedy in itself, as if they were two sides of the same coin. In both cases, laughter is a Trojan horse to enter into direct contact with the unconscious, strike the imagination and trigger visceral reactions. If humor of certain works was enough to pull of anger, fear and amazement out of everyone, the psychoanalysts would be in disgrace ... shame is not enough.

Elena Cué: It is difficult to create a concise profile of Maurizio Catellan. How would you define yourself?

Maurizio Cattelan: I think that the world needs to find a provocateur or a scapegoat, from time to time. I just found myself in an odd place in a fancy moment. No matter what they say, I still think to be the most boring person I know.… I would fall asleep trying to define myself!

Elena Cué: The artist's work is simultaneously highly considered, as well as being an extension of what lies latently within their subconscious. This pure kind of thought; dark and impossible to decipher, becomes very symbolic if it reaches the surface through the creative process.

Has art helped you know yourself better? What do you get out of it?

Maurizio Cattelan: You should ask it my psychoanalyst, if only I had one. Probably I never needed one because my job was a kind of therapy: every work I made was a part of me I got rid of while creating it. Happiness is not about gaining something, it’s more about getting rid of the darkness you accumulate. Apparently, since I retired the treatment is over: I’m not sure it worked, but in the meanwhile I produced a lot of crap!

Elena Cué: You've said you don't consider yourself a conceptual artist, that you don't think.

Is that another joke?

Maurizio Cattelan: I feel I’ve never started being an artist, maybe that’s why it was so easy to decide to retire...I constantly question myself and everything I do, this helped not to take myself too seriously. And I’m not very fond of categories, I find words are terribly dangerous, as they seems to be as definitive as tombstones. This could maybe explain why my works are always “untitled”: it is like writing a joke on my own grave.

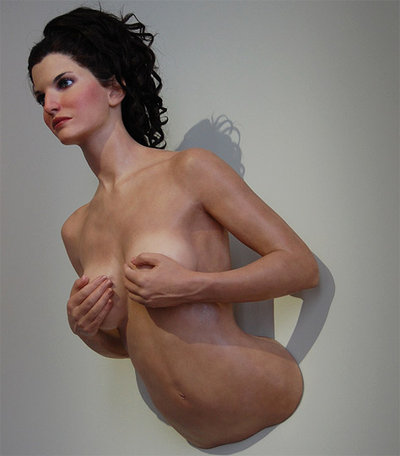

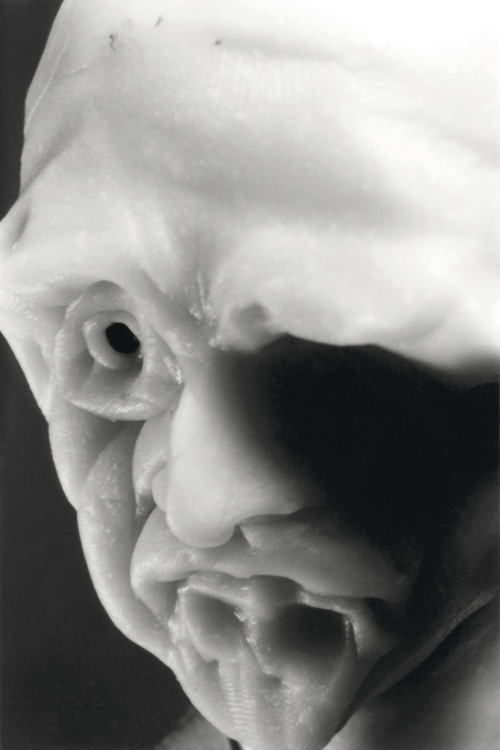

Elena Cué: Meaning and materialization are two fundamental criteria to define a work of art, the subsequent interpretation that each spectator brings to the work can be added as a third criteria (Arthur C. Danto). Given that the materialization of your work is carried out by others, in this case by Daniel Druet, a master in artisan modeling who has created many figures such as Pope John Paul II, Hitler, model Stephanie Seymour and Kennedy.

What importance do you give to the meaning and subsequent interpretation by the viewers?

Maurizio Cattelan: I never asked myself the question in this way, I just searched for images that, in the flood of useless information from which we are overwhelmed everyday, would stir an instictive reaction, from the stomach. Returning to the issue of humor, I think it can be a great way to bring to the surface anger, but without violence. Since the first moment of conception my sculptures were born as images and in that form they continue living in the media. As long as it is a powerful image at first glance, it’ll work.

Elena Cue: Your fondness for using images of iconic personalities holds huge power of communication. Pope John Paul II dying with a suffering expression after being struck by a meteorite in Nona Hora. The image of John Kennedy lying in a coffin with his bare feet in Now. Or Hitler in a smaller than natural size, kneeling in prayer in Him are, for better or worse, all examples of demystification to which you submit personalities who have been political or religious icons for masses of people. You appropriate their power and use it as a weapon at the service of your will.

What do you look for with such provocation and potential irritation that may result in a large proportion of viewers?

Maurizio Cattelan: To me it’s like when you are telling a joke, but no one would laugh: most of the times, provocation lies in the eye of the beholder. I believe there’s nothing wrong with showing people’s vulnerable side, moreover if they’re icons. It might help blur some lines but I don’t think it undermines their status. Quite the contrary, it reinforces their position as well as the belief that they are powerful or sacred icons.

Elena Cue: A very significant work is Bidibidobidiboo, in which your alter-ego is represented by an anxious squirrel in the kitchen where you spent your childhood. It commits suicide with a revolver dropped by its feet. The fact that the name of the exhibition comes from the magical words used by Cinderella to transform her miserable life into a fairy tale add an additional twist to an already surreal situation.

In Untitled 2004, you hung some children figures from a tree with a noose around their necks in Milan. The work lasted less than 24 hours because of the controversy and the anger it raised, which led to such high media coverage that it transformed the work into an iconic piece.

Do you use art as catharsis? Do you think that to affect emotionally, one has to surprise or shock?

Maurizio Cattelan: Someone once said that our heads are round so that our thoughts can fly in any direction: there’s no specific way of interpreting a work, its shape is round such as our heads. People can find a personal path, serious or funny, emotional or shocking, every way is walkable.

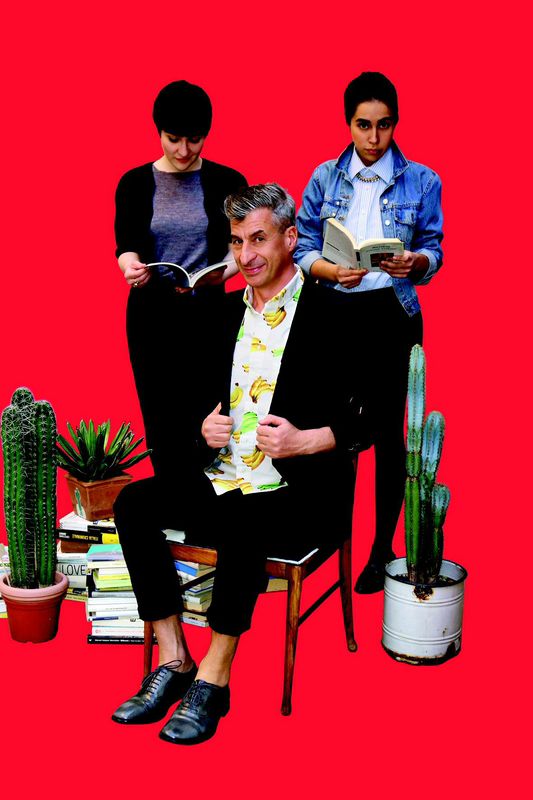

Elena Cué: Sarah Cosulich, the director of the Contemporary Art Fair Artisima has invited you to be a part of the 2014 edition of One Torino. The event will be held at the Palazzo Cavour, and it will open its doors on November the 6th. After abandoning your career as an artist, you will be in charge of commissioning this fair along with the two other young commissioners Marta Papini and Myiram Ben Salah. The name of the exhibition is Shit and Die and it is taken from the installation created in 1984 by Bruce Nauman: One Hundred Live and Die, that included multi-coloured neon phrases on 100 tragic and mundane possibilities to live and die. Shit and Die is one of them. This short declaration encompasses the existentialist worries of the author.

Could you elaborate on the meaning of this exhibition given its bleak name?

Maurizio Cattelan: We thought the combination of declarative ease and uncompromising toughness delves heavily into the universal human experience without imposing a neither fixed or stable meaning. Echoing the title, and echoing the path of life itself, the exhibition is a purposeless journey, simultaneously sad and hopeful, tough and absurd, silly and tragic, slight and profound. In the end, I would synthesize it like this: if you wake up and you’re not in pain, you know you’re dead.

Autorized translation of article, also published by the author in ABC

- Interview with Maurizio Cattelan by Elena Cue - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

One morning in May we arrived at the appartment that Cai shares with Hong Hong Wu, his wife, and their two daughters in New York's Soho district. As he was refurbishing his work studio at the time, we were lucky enough to see his home transformed into a kind of workshop, complete with some of his works lying around on furniture and on the floor. We enjoyed an unforgettable leisurely lunch with the Cai family and some friends, which gave us a great opportunity to observe the artist in his natural habitat: his rhythm, his look, his profound love of music and above all, his way of communicating. Cai Guo-Qiang can be described as one of the world’s most recognized Chinese artists. He was born in 1957 in Quanzhou City, Fujian Province, China, a city known for its cultural openness and religious diversity, due in no small part to its coastal location.

Author: Elena Cué

Cai Guo-Qiang observing one of the sculptures in the Patio during the exhibition I Want to Believe at Bilbao's Guggenheim Museum, 2009

One morning in May we arrived at the appartment that Cai shares with Hong Hong Wu, his wife, and their two daughters in New York's Soho district. As he was refurbishing his work studio at the time, we were lucky enough to see his home transformed into a kind of workshop, complete with some of his works lying around on furniture and on the floor. We enjoyed an unforgettable leisurely lunch with the Cai family and some friends, which gave us a great opportunity to observe the artist in his natural habitat: his rhythm, his look, his profound love of music and above all, his way of communicating.

Cai Guo-Qiang can be described as one of the world’s most recognized Chinese artists. He was born in 1957 in Quanzhou City, Fujian Province, China, a city known for its cultural openness and religious diversity, due in no small part to its coastal location. He moved to New York in 1995, where he began producing, social- and cultural-themed works, but it wasn’t until the end of that decade, coinciding with the sudden breakthrough of Chinese art in the rest of the world due to broader Chinese reform and change within the country, that his work began to be exhibited in the US.

His decision to relocate from East to West has also instilled in him a greater interest in bringing the two cultures closer together. He is passionate about Taoist cosmology, and thus finds himself in a permanent state of profound movement and change. As a conceptual artist, his work recovers cultural memory —via installations, ephemeral ‘explosion events’ and drawings made with gunpowder— in order to tackle ideological issues and historical conflicts with a poetic aesthetic approach. His hometown and cultural roots are always present in his work, evoking an eternal return to a world of nature and spirituality, and a conduit between the world of the visible and the invisible. A recurring theme underpinning Cai’s art is in fact the desire to unite these two worlds; his artworks skillfully and playfully juggle space and time, tradition and contemporaneity, blurring the existing social and cultural limits of any culture, ripping one out of its context and placing it in another to create a new global whole.

Cai Guo-Qiang in front of Odyssey, the permanent installation at the The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2010. Photograph by I-Hua Lee, courtesy of Cai Studio

Youth

His youth coincided with a time of great upheaval and radicalization in China, the decade between 1966 and 1976 (the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution).

Elena Cué: How has the spiritual influence of that kind of upbringing–growing up in an era where the Chinese Communist Party was undergoing a process of ideological affirmation– affected the artist you are today?

Cai Guo-Qiang:The political movements during the Cultural Revolution employed tactics that motivated large crowds. Having witnessed and even taken part in some of the parades during that period, I later applied the same strategies to my art practice. For instance, I often work with large groups of volunteers from local communities to realize my artworks. My goals may be different from the political leaders’, and the ways in which I work with large groups of people may also be different, but it is evident that I am influenced by these experiences from my youth. People of my generation were taught [by Chairman Mao], “to rebel is justified”, and we were told to disregard figures of authority. As a contemporary artist, this gave me the courage to step away from tradition, explore new mediums and new ways of working, and to transform traditional iconographies with my own visual language.

Shining and Solitude, 2010. Gunpowder on paper, vulcanic rock, and 9,000 litres of mescal. From artist's own collection. View of the installation at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, UNAM, Mexico City, 2010. Photograph by Diego Berruecos, courtesy of MUAC

Cai studied stage design at the Shanghai Theatre Academy, and he tried his hand at cinema by participating in two martial arts films. He also dabbled in violin and theatre, and has a wonderful voice that I personally have had the pleasure of hearing. His father, a traditional painter and calligrapher, would paint landscapes on matchboxes, and was a great influence on the artist. “A small space can easily be filled with the corners of the earth”.

E.C: How have all these experiences shaped the person you are today?

C.G.Q: At the Shanghai Theater Academy, the training I received in stage design was different from the art academies at the time. I learned many different approaches to come up with creative ideas: from working freely with different materials, to studying spatial compositions, and these help me create diverse forms of art. The collaborative team spirit and the performance aspect, the emphasis on dramatic effects, the focus on audience interaction or participation in theater, and the temporal nature in artistic expression—all helped shape characteristics of my work.

Refection–A gift from Iwaki, 2004. Remains of a shipwreck and porcelain piece. Size of the boat: 5 x 5.5 x 15 m. Faurschou Collection. View of the installation at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, 2009. Photograph by I-Hua Lee, courtesy C

E.C: In 2008 the Guggenheim Museum organized your retrospective Cai Guo-Qiang: Quiero Creer (I Want to Believe), this exhibition was presented in New York, Beijing and Bilbao, and featured works spanning over two decades of your art production. What does Cai Guo-Qiang want to believe in?

C.G.Q: I Want to Believe is a comprehensive examination of my early works, many of which express a deep-seated curiosity towards the universe and the unseen worlds around us. The exhibition title therefore encompasses all these possibilities, whether they are extraterrestrials, principles of feng shui and Chinese medicine, or metaphysical forces and worlds not visible to the human eye. It expresses an attitude and a sense of anticipation.

Head On, 2006. 99 life-size wolf models and glass wall. Wolves: muslin, resin and skins, various sizes. Deutsche Bank Collection. View of the installation at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, 2009. Photograph ©FMGB Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa, 2009 (Erika Barahona-Ede)

A critical view of mass ideologies is present in Cai’s work, a famous example of which can be seen in the piece Head On, where 99 life-size wolves form a large suspended arch before crashing head-first into a glass wall. The work references the legacy of Nazism on contemporary Germany and that of the Cold War, evidencing the impossibility of learning from our own mistakes (the wolves return to the beginning, starting the cycle once again).

Even works such as Head On, with their solid conceptual baggage, or when dealing with more violent or disturbing subjects, Cai’s works achieve an elegant aesthetic expression: there is harmony in their design and beauty in their form. The artist’s own philosophy is always expressed in an aesthetically pleasing, poetic form.

E.C: What meaning do you ascribe to the Plautus’ phrase “Man is man’s wolf”, popularized by philosopher Thomas Hobbes?

C.G.Q: Growing up, I saw how figurative paintings depicting human subjects—either political leaders or soldiers at war—were used as tools for propaganda, and have thus avoided portraying people in my work. To tell stories, I often use animals as a metaphor for human behaviour. Animals are more natural, more spontaneously expressive than humans, and they can be more easily integrated into exhibition spaces and themes.

Bringing to Venice what Marco Polo Forgot, 1995. Installation which includes a wooden fishing boat from Quanzhou, Chinese herbs, ginseng (100 kg) and other works by the artist. Commissioned by the 46th Venice Biennale. From the Museo Navale di Venezia's collection and private collections. View of the arrival of the boat in Venice. Photo by Yamamoto Tadasu, courtesy of Cai Studio

In 1995, at the 46th Venice Biennale, Cai presented Bringing to Venice what Marco Polo Forgot.

E.C: With your 1995 installation for the Venice Biennale, what did you bring to Venice that Marco Polo had forgotten?

C.G.Q: The year 1995 marked the 700th anniversary of Marco Polo's return to Venice from China after a maritime journey that began in Quanzhou, my hometown, so I decided to make a joke about Marco Polo. He brought back many stories of the East to the West, but he did not tell the West about Eastern thought and philosophy, so I sought to remedy this oversight by bringing Chinese herbal medicine from the East to the West. I brought an old-fashioned fishing boat brought from Quanzhou, and navigated it along Venice's Grand Canal from Piazza San Marco to Palazzo Giustinian Lolin.

The boat docked outside the palazzo, and functioned as a seating area where visitors could savor the medicinal tonics and potions offered inside. Within the palazzo, a modern vending machine was installed on one wall to dispense five varieties of bottled herbal tonics for 10,000 lira each. These drinks were formulated according to the ancient Chinese principle of “five elements,” wherein the five elements of natural phenomena (wood, fire, earth, metal, water) correspond to five tastes (bitter, sweet, sour, spicy, salty) and five organs of the human body (liver, heart, spleen, lung, kidney). The prescriptions posted on one wall enabled participants to select remedies suitable to their needs.

Available along the opposite wall were traditional ginseng soup and ginseng liquor, each contained in a large earthen jar. Visitors used bamboo ladles to pour these potions—formulated to enhance bodily qi, or energy—into porcelain cups.

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Venice Biennale, 100 kilo sacks of ginseng were displayed on a handcart placed near the ginseng service. I applied the idea of healing a living organism and its energy flows to the city and its canals. Inside the entrance of the palazzo, I hung a plastic curtain that was filled with canal water and covered with common acupuncture meridian charts, and symbolically pierced it with acupuncture needles.

Legacy, 2013. 99 life-size animal reproductions, water, sand, dripping mechanism, various sizes. Collection of Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. View of the installation at the Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 2013. Photography by Queensland Art Gallery ׀ Gallery of Modern Art

In 1966, in the first days of the Cultural Revolution, the People’s Liberation Army decided to create a portrait on the mountainside by carving it out in the rock — what Cai describes as his first contact with Land Art. This relationship between man and nature is very present in Cai’s work, something he reflects on in his latest exhibition, Falling Back to Earth, his first solo exhibition at the Gallery of Modern Art in Queensland, Australia.

E.C: Does this fall back to Earth symbolize a need to return back to your roots, to nature?

C.G.Q: The title of the exhibition Falling Back to Earth conjures a sense of yearning for the spirit expressed in Chinese literati paintings of earlier times, when people lived humbly and in harmony with nature, an ideal that stands in opposition to the way in which people interact with nature now.

The Ninth Wave, 2014. The installation includes 99 life-size animal reproductions, wooden fishing boat, white flag, electric fan. Size of the boat: 17x 4.55 x 5.8 m. From artist's own collection. Commissioned by the Power Station of Art, Shanghai. View of The Ninth Wave navigating across the Huangpu River near Bund, Shanghai, 2014. Photography by Wen-You Cai, courtesy of Cai Studio

The ecological and environmental crisis that China is suffering is at the heart of his latest exhibition, The Ninth Wave. It is also the first solo exhibition of a living artist at the Shanghai Power Station of Art. In it, an apocalyptic Noah's Ark - a fishing boat full of dying artificial animals - navigates the Huangpu River as a symbol of the dangerous present-day situation. It is also a recognition of the need to return to nautre and to our spiritual roots.

E.C: Do you believe that Art should serve a moral, social, political, or cultural end... Or should art be the act of expressing our unguarded passion?

C.Q.G: There are many types of artists, and there are no hard and fast rules on how artists should act and behave. Otherwise art will turn into history and become static, rather than constantly improving and changing with the times.

History's footprints: Fireworks project for the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games in Beijing, 2008. The display took place in Beijing on August 8, 2008. Commissioned by The International Olympic Committee and The Beijing Organizing Committee for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad.

Photograph by Hiro Ihara, courtesy of Cai Studio

He lived in Japan between 1986 and 1995, where he got to know and use gunpowder as a tool for art, and which eventually became the art form for which he is globally known. Gunpowder has become an artistic creative source that defines his identity as an artist; this powerful material has been used by the artist as transformative energy to create drawings and ‘explosion events’.

His work includes a number of dichotomies: a mixture of traditional symbols — acupuncture, dragons, powder — and contemporary ones (time), a merging of East and West (space), and the contrast between yin and yang, destruction and creation (opposing forces).

E.C: Your interest in time and space, opposite forces and cosmology are evident in your work. What is your guiding philosophy in life?

C.G.Q: In the I Ching, or the Book of Changes, “I” means “change”, and this is important. There are also two doctrines I embrace in Daoist philosophy: “no law is the law”, and “leveraging others’ power to exert your own strength”. In Confucianism, tolerance is a value that has taught me not to exclude others, and to learn from and work with people of different cultures; it enables me to find new possibilities in art. These underlying principles are the most valuable lessons I have learned from Eastern philosophy, and they are more important to me than superficial symbols (such as dragons), or even gunpowder as a choice of artistic medium.

Tree with Yellow Blossoms. Photo by I-Hua Lee, courtesy Cai Studio

Authorized copy to Alejandra de Argos of article originally published by ABC

- Interview with Cai Guo-Qiang - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Fabrizzio Morales-Angulo

Author: Fabrizzio Morales-Angulo

Olivia Bee: Enveloped in a dream. Bernal Espacio Gallery, Madrid.

We all have memories, all adults have suffered through adolescence, and almost everyone has pictures from that age. Images that take us back to past times of solitude or in the company of those who were special during those years. Images that make us remember friendships already forgotten and sensations that were unique and marvelous in that moment.

Olivia Bee has made all of these moments of her life stay frozen in the images that she has captured, and after being developed, they became something else. Olivia made it so that somehow we can live these moments with her through her photos. During a few seconds we are there with her, we are young again and we run through the snow with her. We accompany her while she looks through the window, or even while she photographs herself in an old printed armchair. Her photographs make us relive our own memories while, at the same time, we want to be part of her own.

A diary in snapshots, composed by micro-stories of one photograph that stimulates our imagination, makes us think of, in a nostalgic way, our lost youth, one that could be, one that really was, and the one we wanted.

Her recent past become oneiric in our retinas. This photographer is like the tiger cub who hunts by instinct, roughness and without any over-thinking. Her way is like a need: it is fed from the innocent moments of her life and the lives of her friends.

Olivia is insultingly young and belongs to a new generation that has been raised, educated, fed, and well-informed with images and videos. Their experiences are immediate, the information is global, the distances are virtual, and the whole world can be reached with a single click. In a new era where social media dominates our lives, where the hurry to catch the moment is more important than to live it, there exists an even bigger hurry to share it. It is a pleasure to stop, not think, rest, and look back, even if we've done it through images of someone else´s life, this time Olivia Bee's.

Fabrizzio Morales: You started to photograph very young, you knew what you loved. Did your parents supported your talent and your passion?

Olivia Bee: My parents have always been incredibly supportive. They always gave me everything that they possibly could. They kind of just let me do my thing but told me when I screwed up. I'm very lucky. My family is amazing.

FM: How important is people's support for you and your work?

OB: I am pretty faithful to myself in terms of art (most of the time). I know how to push myself and am pretty level-headed, but at the same time know that I am capable and that I can and will achieve my dreams (at least I hope!!). I think I would be fine without support because I definitely support myself and am very stubborn, but support definitely helps me a lot. I'm very lucky to have friends and family that love and believe in me and a boyfriend who is the same. I am very blessed.

FM: In your own photographs, you capture beautiful and very intimate moments of you and your friends' life, how do you know when to stop and change from protagonist to an external watcher of your own experiences and photograph them?

OB: This is something I am working on, internally. Knowing when to snap and when to put it down. I don't want to use the camera as protection.

FM: Analog or digital; developing or computer editing; dark room or photoshop - what are your preferences?

OB: I love both. Each comes with its own advantages.

FM: This is the first exhibition in which your pictures will be on sale, and some have already been sold before its opening - how are you finding this new experience?

OB: It's not my first! I had an exhibition in New York this summer called "Kids In Love" that I sold a lot of pieces at too! But it is amazing. But it's also weird to sell pieces that are so close to my heart -- but at the same time I want to be able to share them with other people.

Enlaces de interés:

- Olivia Bee: "Enveloped in a Dream", Bernal Espacio - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marta Gnyp

Autor: Marta Gnyp

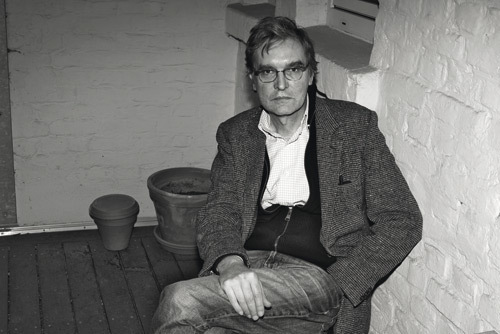

German artist Thomas Schütte has long been one of the most interesting and unpredictable European artists. During the last 30 years, he has built up an impressive oeuvre of visually and intellectually provoking works. This interview is a combination of two conversations which we had, the first one in 2010 and the second one only recently in 2013.

Thomas Schüette

Marta Gnyp: I read somewhere that when you visited Documenta V in 1972, where you saw the works of Sol Lewitt, Blinky Palermo, Daniel Buren you decided to become an artist.

Thomas Schütte: I also saw photorealism, which is completely forgotten now and which was at that time the main public attraction, art brute, landscapes, objects and so on. I was old enough to understand that even at that time, everything was possible. Every thinkable position was simply in this show – actually I went two times in the summer of 1972.

MG: You were interested in art before you went to Documenta?

TS: Yes, but I have never seen any exhibition. I knew paintings and sculpture only from books. In Kassel, I saw for the first time all the variety of possibilities in the art world.

MG: I assume that you used to make art yourself at that time, that you knew that you had a talent?

TS: Talent? I don’t know, but I was interested.

I had a film camera and I made an 8mm film, which by the way I still have. I went to the city library once per week and read everything they had about art.

MG: During the Documenta you discovered that art offers so many possibilities that you decided to be a part of it?

TS: Yes. The other reason was more practical. At that time, there was a boom of students at universities. For all faculties except art and religion, you needed an entrance exam, which I didn’t want to do. So I decided on art. Firstly I applied to the two famous film schools in Berlin and Munich where the important German filmmakers like Wenders and Herzog were working. I discovered that, unfortunately, I would need three years pre-education to enter the film academy, which I was not prepared to do, and they told me, that film is an industry, not for outsiders, who want to do things by themselves.

MG: So fine art was the only option you had?

TS: Actually I had no option; options came later. The word “option” always surprises me. It is a part of the computer language, which hasn’t existed before. 15 years ago, I was discussing with students about art and I remember them talking about options: there is no will, there is no need, but there is an option. Nobody had the energy to do something against all odds. This attitude was so shocking to me that I tried to find out where this “optional” thinking came from and I discovered that the computer is the source of it, since you can work there on many things at the same time.

MG: Could you see an option as a possibility of a conscious choice?

TS: Of course. Our generation was probably the last one without the options; we knew only good and bad, up and down, right and left. 200 kilometers from the place you lived, the world stopped at the Iron Curtain, right next to Kassel actually. There was no option, there was a finish. At the end of the 80s, the unification process and the introduction of computers changed the whole world.

MG: The 70s were for you the formative years. Was it easier?

TS: I think so. If you speak to young students today, they seem pretty confused, but on the other hand my own kids seem to be very structured.

Innocenti, 1994, b/w photo, ed. of 3, 75 × 50 cm, photo: Thomas Schütte

MG: Are you teaching?

TS: No, I don’t want to be responsible for young people. I change my mind too often.

MG: Do you consider working with your hands and materials more honest than the omnipresent quasi-conceptual approach?

TS: I have to know my limits. Some time ago we started a four-meter high figure. I cut the head out of styrofoam, which was one meter high. Someone who helped me went away and I was all alone with the head. It was very hot. After one hour working, my body said, ‘it is enough. I had to sit down and smoke a cigarette. ‘ You have straight limits – either of the material and tools or of your own body, your ideas and concepts. When working with physical materials you always have an enemy.

MG: Are you fighting with the object you are making?

TS: Sometimes I am. The basic idea is, however, that you don’t see the fight at the end. It has to look easy and natural.

MG: Do you have assistants?

TS: I have my own assistants only for the computer work. Everything I’m not interested in I try to keep outside. In the workshop they prepare a sketch or a dummy and then I’m doing the rest. But basically, you need help, especially if a piece is larger than yourself. My workshop is extremely efficient. I do ask a lot of people when the work is half finished what do they think, and I like to work with good craftsmen and try to follow their ideas.

MG: Who are these people? Your gallerists? Your friends?

TS: Critics or people who are doing art, but mainly the fabricators. It is not that I’m completely alone in my studio at 2 in the morning breaking my head about a work. No, I close my shop at 6 or 5 p.m. I stop during the rest of the day; I try to relax because the ideas don’t come when you are stressed.

MG: Since the 80s you have been sporadically involved in the architectural projects. Why did you get interested in the architecture?

TS: There have been 10 or 11 projects so far; I do it like every two years. It is fascinating because the concept is completely different. I like to have a work that is situated in reality, since museums are fictions for a short moment. You cannot take this permanent work to Christie’s either. Besides, if it is for a permanent use it requires a different way of thinking. The buildings address a difference audience in comparison to the thousands of the museum visitors who come and go. It is also different because of its functionality aspect: it has to bear harsh weather conditions, the door has to close, and the window must go open. It has to function but at the same time all these buildings are very surprising.

MG: You are also responsible for the production of the work?

TS: Sometime I build like 3 or 4 models, to find the proportions and so on. I follow production closely, I interfere when it goes wrong, but I’m not the architect, neither I’m responsible for the costs and details of the construction. The architect has all the troubles, and I have all the fun, but sometime I have to compromise, too.

MG: Is it difficult to convince you to make a proposal for a house?

TS: I charge a cup of coffee, a good steak and the taxi to the airport.

MG: So you design it only for people whom you know well?

TS: Good acquaintances. It makes me fun. I make mostly pavilions or teahouses. The translation of the word „pavilion“ means a house of pleasure, a house for fun.

MG: Do you try to escape the pressure coming from art institutions and your galleries?

TS: Nowadays, galleries are working with deadlines. In the 80s, there were workshops in the galleries; you could come whenever you wished, they had equipment and a working space. The moment the computers moved in, suddenly galleries got glass tables, computers, the personnel that consists of mostly perfectly dressed women who don’t even say hello. You cannot make noise or dirt. Today’s galleries look like a shoe shop – not like a workshop. There is only one gallery I have seen during the last 10 years where things were different: when the owner began to paint a wall himself because I found it not gray enough. I was painting my artwork, while he was painting the wall. It was a small gallery in Burgundy called Pietro Sparta, which is in the middle of nowhere, but people know it because the region is famous for its great food and fantastic wine. The Italian owner has been working with artists like Luciano Fabro, Mario Merz, Jannis Kounnelis for 20 years without any art education. For me he even built a 20- meter long house, as a full scale model, just for fun.

MG: Is this an ideal gallery for you?

TS: When I started to work with some gallerists like Philip Nelson, Ruediger Schoettle or Konrad Fischer, we were like a family. They had time for you. It was completely normal to spend evenings with Mario Merz or Gerhard Richter. No money, no pressure, no sales, perhaps one or two works during one show. The gallery consisted of the owner, one secretary and one craftsman, while today’s gallery relies on one boss who is sitting in a plane with two telephones and 20 employees. In the 80s, art became business. The business people came into the art world. You never see them for they buy and sell on the telephone. Since the 90s, art became an industry – they started to produce art works like cars. They can destroy artists by bad press and the merciless pressure to sell. The industry even can produce their own artists. Konrad Fischer used to complain, when the show was sold out: what have we done wrong?

Amuseument, 2002, wood, perspex, elecric light, 194 × 170 × 230 cm, photo: Nic Tenwiggenhorn

MG: Are you are suggesting that in the current art world everything could be constructed?

TS: Yes, this is the reason that sometimes I’m losing my interest in being on art fairs or even big group shows.

MG: Don’t you think that there is still great art being produced?

TS: Once in a year I see a show by a living artist that really touches me. Other works are good but not touching. It is different regarding dead artists. The older you get the more you are interested in old and classical positions.

MG: Your show in the Serpentine Gallery in London referring to the classical subject of the portrait was a great success. Even the English press was very positive.

TS: The London press was pretty enthusiast, which is indeed unusual.

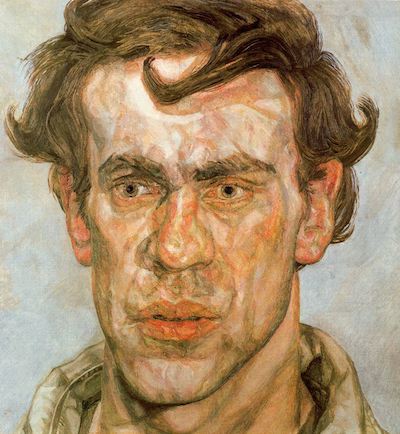

MG: What was the reason that the public was so excited?

TS: I found out after the show has opened that without knowing it we pushed up three right buttons. The first one is the figurative monument. England is one of the few civilized countries in the world – except dictator countries -, which has still a tradition of installing monuments of politicians like Ronald Reagan or other famous people or war heroes, throughout the city. They have a system of commissions of monuments. I also found out that they have a tradition of portraits. They have the National Portrait Gallery with photos of Mick Jagger, sculptures of the Queen, or paintings by Lucien Freud, whereby upstairs in the building there are historical portraits of the last four hundreds years. They have a national prize, the British Petroleum Prize on portraits that generates a lot of attention, there you can see how not to do things. And as the third thing, they have the tradition of watercolors. They have the National Watercolor Society and the Prince is doing watercolors, like many other people.

I touched all the three soft spots of this country without knowing it. I just did it by instinct. That’s why it was so positive reaction.

MG: You showed plenty of works from different periods, mostly from your own storage. How come that your work doesn’t lose on actuality or at least that people see it as actual?

TS: This was the job of the curator Hans Ulrich Obricht who came with the idea of portraits. This was not my idea but I quickly said yes, made a list of works and we could install it in two and half days. Luckily I left the space open, followed the line of the building and I didn’t exhibit too many works. The interest of the public was huge; every day 1500 visitors came to visit the show. I’m happy to see that it is possible to work in England and to have success without the usual scandals.

MG: Are you not amazed yourself that everything you make turns out to be a success in the reception of the public.

TS: I don’t believe it. I don’t read the articles. I look at the headlines, I look at the photos and I read the first and the last sentence, the text between them I don’t. If you start to believe in it you are lost.

MG: Still, why is it now the time for Thomas Schütte? Why does the public want to see you as a great artist?

TS: I don’t know. Possibly because I make less stupid mistakes than the others. I am out of this art fashion industry. I am always trying to do something new, there is no repetition of one product, and I’m not a brand. I want to be an artist and not to be a brand. The brand artists are on the other end of the rainbow.

MG: Are your artworks also surprising for you?

TS: This is exactly why I’m doing it, to entertain myself.

Große Geister, 1996-1998, exhibited at De Pont Foundation for Contemporary Art, Tilburg, Netherlands, 1998, height approx. 250 cm, photo credit: Nic Tenwiggenhorn

MG: Do you see any coherence in art that has been produced in the last 20 to 30 years?

TS: This is a job of the critic to see and explain these processes but during the last 20 years, the critic missed the train. The art industry uses the word of the critic to sell but they never pay them. There is no money for the critics, there is no audience for them, they have no big platform. There was a certain time that the artists wanted to please the critics or the museum directors. This is one of the reasons that you could find the secondhand conceptual art everywhere. I have no idea what survives and what not. It feels very much pornographic – use and abuse.

MG: What became clear to me looking at your works and reading your statements is that freedom and equilibrium are the main concepts of your work: to have as many possibilities as possible and to reach a kind of balance. You don’t like to repeat an idea; you are using elements from architecture and theater, you are using different media. Are you permanently searching for something new or you don’t want to commit yourself to one territory?

TS: It is not always searching for new. There was a moment that I took old objects and transformed them. There was a strange feeling that the vision was suddenly out. For many years, I had a coffee with a cigarette and I immediately had an idea. I wrote it down and I made it. But suddenly everything became a black hole.

MG: When did it happen?

TS: Some years ago. I still have sometimes the problem to get myself motivated so I can start with existing things and work from there.

MG: Why did you lose it?

TS: A breakdown. I made sometimes 15 gallery shows per year. The result was that I had three times a complete burn out, the last 30 years, so serious that I had to go to hospital. So I protect myself now and concentrate on nice things.

MG: I would like to speak with you about a very special work – Grab (1981) – in which you depicted your own grave with the date of your death. Why did you make it?

TS: This is a model for a gravestone. I think everybody in the age between 20 and 30 gets the idea about mortality. I got it out of the blue walking through a graveyard. I went home, I made a drawing, cut out the shape of a family house, I put my name, the date of birth and I couldn’t leave the end empty, so I decided to put the date over 15 years: 25.03.1996. I gave myself 15 years because I thought by then I will be dead anyway. Firstly, because I was smoking, heavily drinking and working much too hard. Many people die at the age of 42, naturally or by suicide. It is a very critical year for a man. Secondly, in the 80s there was no idea to survive the millennium change; anyway the end of the century was the end of the world, very apocalyptic.

MG: Were you not afraid that you were provoking the fate?

TS: When this date came it felt strange. I was surprised how strong this piece is. I keep it for myself like many other old pieces. It is interesting to project the end of all, but nowadays I forget this day.

MG: Also scary?

TS: No, what is scary about the death? At a certain age it can come every day. Death is the idea that keeps you away from all the nonsense. What is really interesting is the shock of mortality when it comes.

MG: Do you experience the shock of mortality sometimes?

TS: Every morning, to get myself motivated, to get dressed and step out of the home.

MG: You chose Seneca’s writings as a part of your catalogue several years ago. According to Seneca, the happy man enjoys personal freedom and autonomy and he can be defined as one who thought the gift of reason has neither desires nor fears. Is this your ideal of a happy life?

TS: If you are lucky.

Mann im Matsch – Der Suchende, 2009,

Composing bronze components at the foundry, photo: Luise Heuter

MG: Would you like to live a life without desires?

TS: I’m not a priest. By the way, they have hard time at this moment. We faced the crisis of communism, capitalism, then banking system, the state system and now the religious system. Only the art system survived and is still getting stronger. It is so strange: the museums are full whatever you show. Works are being sold no matter how deep the crisis seems to be. The art didn’t collapse.

MG: What do you think is the reason?

TS: I don’t know. Maybe because the art has incorporated a self-critical aspect, which other institutions are missing, they forgot how to rethink the subjects. The contemporary or modern art system that has existed since 150 years has a critical system, like a permanent revolution. We learned, even successfully artists don’t believe in what is said, they try to continue.

MG: The demand for your shows must be big.

TS: The best way for not doing shows with the galleries is to ask them to give me an idea. There is no idea, this people have no idea, and they want products. They have a huge system and huge spaces, especially in London. They have only one idea, get the works in and get them out, and to collect huge prizes. So the polite way to say ‚no’ is, if you have an idea I will do it.

Stahlfrau Nr.2 / Steel Woman Nr.2, 2000, steel, 137 × 125 × 250 cm, photo: Nic Tenwiggenhorn

MG: Do the collectors also approach you directly?

TS: Yes, now the collectors hire museum people, build big buildings for their collections and sometimes come to me. I’m not pushing it but if it is interesting to me I do cooperate.

MG: Do you sell your old works?

TS: I basically don’t sell what is in my storage; it is for my 3 kids and myself.

MG: What do you think about the huge sums of money being paid for your works?

TS: 20 years ago I made this model puppets for United Enemies, each evening. Nobody wanted it in the beginning; they were too small, like 40 cm. We showed them, but I had to stop in a certain moment because we couldn’t get the glass tops anymore. The production was stopped in Czechoslovakia. Now the puppets are at auction for 1 million $. To double the price is ok, 10 times the prices is ok, the poor collectors have to earn as well, but to increase the price 100 times? I better keep it for myself. The collectors now are all dealers, somehow. They are buying and selling, only the buying is public and the selling is not publically announced.

So I try not to do more than one gallery show per year.

MG: How does it feel? It must be also very exciting to know that your works achieve such horrendous prices?

TS: When I feel very bad I go to my storage and see 30 steel women on top of each other, in the shelves. It is my life insurance. Even in a bad year I can make good shows. A museum cannot effort to lend 50 sculptures, 50 drawings or 50 photos etc. Every collector asks a fee, the costs of transportations are so huge that only big museums can do complete shows and only the rich artists because you have to bring a lot of money by yourself.

MG: Did you co-finance the Reina Sofia show in 2009-2010 for example?

TS: No, for this exhibition I was completely out. I found it too big for me, especially because the social crisis was already visible 3 years ago. I felt guilty. I was not involved in the installation of the exhibition; my assistant was there. I was completely out of this project.

But for each show, for each book as an artist you have to bring an edition. Sometimes it is easy, sometimes not, but this is the way to collect the money for the many books.

Kardinal, 2005, silicone, steel, blankets, height: 250 cm, photo: Nic Tenwiggenhorn

MG: Do you consider this money-related development of the art world as positive?

TS: It is a big mistake. 1 % of the artists are visible and 99% are considered as losers.

MG: Do you follow what is happening in the art world?

TS: I don’t read art papers. I get a package every three months but I leave in the plastic. I have things to do. Silence is interesting.

MG: You are not afraid that you are doing something exactly the same as someone else?

TS: In my field there are not so many people. I don’t know anybody who put flowers on the table and draw it. Nobody is doing this. It is a very interesting game to make.

I really like to do the things nobody is into. Like flowers, faces, portraits, houses, neglected things, coming from the tradition.

MG: The tradition is for you a part in making art?

TS: You cannot make art, you only can make art happen. This is the only thing you can do, prepare yourself and things will happen. Art happens. For example drawings: you can bring yourself in the mood to make a drawing but you cannot force yourself to create.

MG: How do you prepare yourself for this?

TS: By sleeping, by doing nothing or listening to the music, waiting. Many days nothing happens and than all of the sudden it is there.

Frauen, installation view from De Pont Foundation for Contemporary Art,

Tilburg, Netherlands, 2006, photo: Peter Cox)

- Interview with Thomas Schütte - - Home: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

|

Contributor: Maira Herrero, |

|

German historian and journalist Florian Illies’ 300-page book is a humorous, fleeting look at the main cultural events in Europe just before the Great War.

Illies’ book is neither novel nor essay — it is simply an account of the key creative and cultural happenings in those twelve months of the year and their effects on society and culture, moments before the advent of the bloody massacre that would subsequently rock the very foundations of Western thought.

It’s an attractive read for anyone interested in the artistic avant-garde, the influence of psychoanalysis on later thinking — particularly at the Frankfurt School —, the great literary works and cultural milestones of the time and the shift in perspective that was spreading across Europe, coinciding with the gradual disappearance of the existing lifestyle. Western culture found itself launched to heady new heights thanks to technological, industrial and artistic progress, only to collapse tragically not long after.

The book follows two parallel threads, on the one hand the epistolary relationship between Kafka and his beloved Felice Bauer, and on the other the turbulent relationship between Alma, Mahler’s widow, and Oskar Kokoshka, as told through his well-known painting Bride of the Wind (1913-4).

During the twelve months of 1913 we see the 20th century’s greatest creators come and go: Arnold Schönberg and Igor Stravinsky and radical new musical forms; Freud and C.G. Jung’s civil struggles; the break-up of the Der Blaue Reiter (Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Albert Bloch, Robert Delaunay) and the Die Brücke groups (E. Ludwing Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, etc.); the rawness of George Grosz’s paintings, an example of art as weapon against authority; the innovative architectural styles of Peter Behrens (who just a few years earlier was responible for the turbine hall at the AEG factory), Walter Gropius, Adolf Loos and many others who placed light and symmetry at the centre of their work.

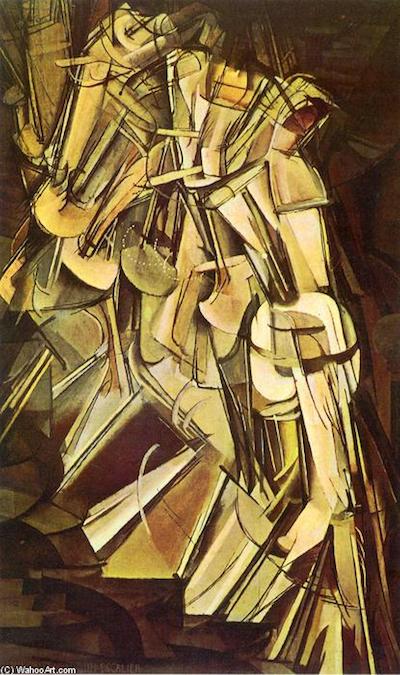

“It was as if the current art exhibition coming from Europe had fallen on us like a bomb”, reported the publication Camera Work on the exhibition running at New York’s Armory Show at the beginning of 1913. American visitors found themselves completely stunned by Marcel Duchamp’s Woman Descending Staircase (1912). In Berlin, a few months later, the legendary art gallery Sturm would host Germany’s First Autumn Salon, a collection of avant-garde works (with the notable exception of the Die Brücke painters). Gertrud Stein was the epicentre of Parisian art, her home a meeting place for established artists such as Picasso, Matisse and Braque. The collector Eduard Arnhold regularly would host regular meetings with Emil Nolde, the great Berlinese patron together with James Simon. Writers, thinkers, editors, merchants were everywhere to be seen.

Paris, Berlin, Zurich, Venice, Vienna, Munich were some of the regular haunts of the progressive class of the time. Cities were gradually transforming into large metropolises; fashion was becoming an integral part of a new kind of lifestyle.

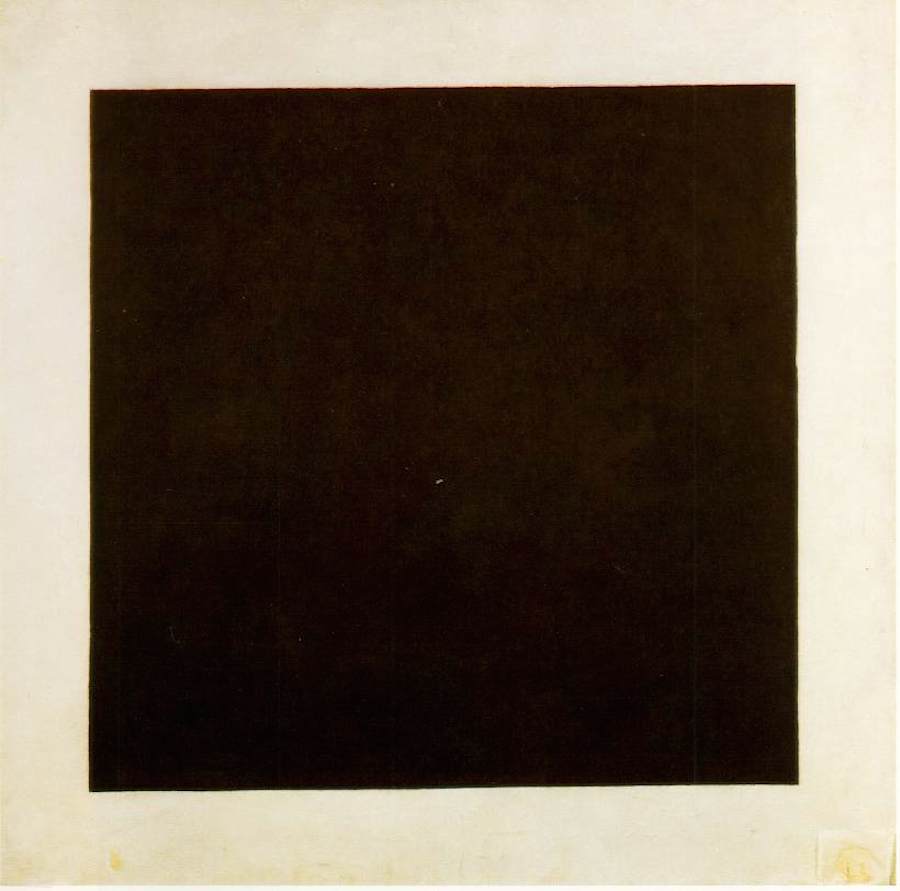

The book thankfully includes numerous comical anecdotes and stories which, although they don’t strictly belong to the year the book focuses on, appropriately adorn the tale. One could almost call 1913: The Year Before the Storm a guide to the fascinating world of exuberant creativity, finally ending with the Suprematist manifiesto and Malevich’s Black Square (1915).

Florian Illies. 1913: The Year Before the Storm. Salamandra, 2013.

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel.

Art Historian

|

|

Chekhov and his wife, actress Olga Knípper.

"Give me a wife who, like the moon, will not appear every day in my sky." (Chekhov)

Throughout 2013, after Alice Munro was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, it was impossible not to hear someone saying that Anton Chekhov (1860-1904) is "the father of modern literature". So a few weeks ago I decided to sit down and re-read "The Steppe", and I found myself once again with a strange, uneasy feeling inside me, as if something had remained there, deep down, undigested.

The 150-page novel is about the journey of a child over the Ukrainian steppe set around 1880. For Chekhov, the Russian soul was something dependent on the unparalleled solitude of the steppe landscape, something he wanted to describe slowly, gradually, as if through canvases, page by page, revealing themselves - a creative process one could describe as written painting.

How many painters, illustrators or film directors have been able to convey a storm as convincingly as Chekhov?

The true protagonists in the book are not people but the vivid descriptions and the landscape. Apart from these standout elements, though, it's a generally slow read with very little action.

So if nothing much happens, how do we explain the impact it has on the contemporary reader?

It's a pertinent question, particularly in an age of immediacy, information overload and expectations of complex, highly elaborate content. In the midst of recent Oscar-winning films about relationships between a man and an operating system, or the full-on anxiety of a space mission gone wrong, what can we hope to get out of a book whose opening lines describe the flight of a bustard? Why are we so impressed by the description of time passing one morning in the countryside, as if it "stretched endlessly, as if it had stopped altogether"? The author makes us excited to see how he unravels the decline of Russian society at the end of the 19th century through the actions of an old priest. "Father Jristofor had never experienced a concern so strong as to tighten his soul like a boa."

Further answers to these questions can be found by making parallels with the world of painting.

When we study Jan Van Eyck's "Man with Red Turban", for instance, we start looking at each and every strand of mink hair on the neck, we study the eye closely, and we even discover a tiny drop of blood in it - it's a similar mental slap to the one we experience when scrutinizing Freud's "Portrait of the Young Painter".

Looking more broadly, it's also similar to the "tornado effect" caused by, say, Chekhov's (or even Thoreau's) letters, or David Forster Wallace's novels.

Perhaps it's merely the fact that all these works of art come from a place of genius. They have all left us with some sort of sting in a corner of our hypothalamus, an intense, uneasy feeling that's difficult to shake off. We're predators of emotions and we recognize our catch.

- Details

- Written by Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca

|

Contributor: Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca, |

|

Art is a pleasing, entertaining, educational trick of the imagination. In and of itself, a piece of art, a creation, is nothing more than the physical outcome of life’s primal creative energy. Ultimately, creating art and living life are one and the same activity, life being the continuous creation of a world of appearances being continually produced and destroyed, playfully, exhilaratingly. Hence, for art to exist, there must be an abundance of force, a personal vital intensity that spreads out into the world creating and destroying forms and objects. That is the essence of art: the drive behind it is nothing but the same creative and destructive energy underlying all action in the world.

So how exactly does this great energy work? By taming a large number of impulses to form a harmonious, beautiful whole. This process happens in the natural world, for instance: every living creature moves according to a certain rhythm, and every living creature naturally generates its own rhythm as part of its life, so much so that we can actually define life as a spontaneous, rhythmic mechanism. This is clear from our own personal experience: we would rather engage in rhythmic than disorderly effort. In sporting practice and other physical activity, by repeating the same movements in equal time intervals we use our muscles efficiently thus saving a great deal of energy and avoiding unnecessary fatigue.

The idea of rhythm underlies life and movement within both the organic world and the inorganic world. There is rhythm wherever there are forces that are not in balance with each other: cold and heat, humidity and dryness, density and expansion, light and darkness. Everything that exists has a natural tendency to fight, and thus rhythm is generated from the counteraction of opposites: the rhythm of the seasons, the cycle of day and night, rainfall and drought, hunger and satiety. As Heraclitus said, all occurrences are in some way connected to rhythm. From this we can conclude that life, existence and evolution are all about creating balance to counteract an underlying unbalance, controlling disorder through regularity and organization, creating a world, an order, from chaos.

Similarly, art is not the boundless unfolding of sentimental longings or wild fantasies, but the successful pairing of content and form, inspiration and technique. And the more the creative force behind the artwork is contained and controlled within the limits of an artistic form, of a rhythm, the more sublime the results will be. So where does this theory take us?

When we listen to good music, we experience this very human desire for depth, infinity and essence; when we look for sublime thoughts in times of calm reflection, we risk upsetting the correct balance between form and content. The best kind of music should content itself with the ways of our world and our lives, and should love them just as they are, as simple appearances, without trying to surpass them by looking for some transcendental meaning. Music, as an interplay of melodies and rhythms, is in some sense a privileged way of thinking about the truth behind appearance, since its very artistic form allows us to understand the world — not in a profound way, but as a tragic-Dionysiacal creation-destruction way. The artist’s rhythms, songs and harmonies, those which inform his work, refer to the Earth and to life, which is nothing more than a swing alternating between birth and death.

What’s interesting is that music doesn’t have to originate from pessimism or asceticism, as Schopenhauer thought. In fact, it could even become the true countermovement of pessimism: “I would only ever believe in a god that could dance”, said Nietzsche. Which is something like asking music to be the art of lightness, of versatility, of subtlety and of pure joie de vivre. What music teaches every human being is to live every moment fully by controlling the chaos, giving life a meaning and imposing a certain order, a rhythm, a shape to its unpredictability and its temporality, giving it a universal shape and directing it towards specific goals. If this process is not followed through, then one will be overcome by chaos, by a multitude of impulses, by the unpredictable, ever-changing determinations that are all around us.

In conclusion, the music that manages to overcome chaos is the type of music which can be said to be life-affirming, that which is in synchrony with human well-being and which is capable of ordering time, rather than passively and nihilistically succumbing to a seductive aural chaos which, while superficially appealing, is harmonically and melodically disorganized. This is how Nietzsche envisioned Dionysical music — on stage, the music should be playing on it own, with no distractions, free to inspire a sense of vitality. The best form of music, therefore, should be absolute music, a representation of both the beauty seen as the form of that which has been overcome, but also as the sublime which continually breaks any form induced by an impulse of a new and profound fullness.

Diego Sánchez Meca