- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

Rarely have spectacles been the protagonists of an execution. But those of Khaled al Assad had seen too much. Worn for over four decades by the Head of Antiquities for the ancient city of Palmyra, they had overseen the care and upkeep of every pillar of the great colonnade and every sphinx at the temple of Bel. In the spring of 2015, Al Assad was living a peaceful life in retirement but still fully committed to 'his' ruins. At the beginning of the Syrian conflict, Palmyra had seemed safe behind combat lines. However, in May of that year, ISIS militants were drawing closer. While the entire city emptied of its inhabitants and its resident Syrian army fled, the 82 year old Khaled al Assad came up with a plan.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

The execution of 25 Syrian soldiers by ISIS, Amphitheatre at Palmyra, July 2015

Palmyra after ISIS: The destruction of World Heritage sites and other forms of terror

Rarely have spectacles been the protagonists of an execution. But those of Khaled al Assad had seen too much. Worn for over four decades by the Head of Antiquities for the ancient city of Palmyra, they had overseen the care and upkeep of every pillar of the great colonnade and every sphinx at the temple of Bel.

In the spring of 2015, Al Assad was living a peaceful life in retirement but still fully committed to 'his' ruins. At the beginning of the Syrian conflict, Palmyra had seemed safe behind combat lines. However, in May of that year, ISIS militants were drawing closer. While the entire city emptied of its inhabitants and its resident Syrian army fled, the 82 year old Khaled al Assad came up with a plan. Mere hours before Jihadists entered the city, he summoned his son, Walid, and his son-in-law and together they selected 900 of Palmyra museum's most valuable pieces and organised their evacuation to Damascus by lorry. These are immediately followed behind by Walid and Assad's son-in-law, married to Assad's daughter whose birth coincided with the setting up of Palmyra's sentinel and who was named Xenobia after the Great Queen of the "pearl of the desert" herself.

The rest of the story is well-documented. Jihadists take the city, explosions are heard coming from beneath the temples of Bel and Baalshamim as well as the Arch of Triumph and the funeral buildings are riddled with mines. Images flood the newsreels and internet. Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO, calls the events a war crime. With the amphitheatre behind them, 25 beaten and bloodied Syrian soldiers are shot at point-blank range by the 25 sons of Jihad fanatics standing behind them, the oldest of whom appeared to be around 12 years of age. The backdrop is a huge black Caliphate flag. ISIS mobs waste no time getting into the museum where, to their astonishment, they find the walls bare and the showcases and pedestals empty. All that is left is an elderly man, in his office, waiting patiently for them. Al Assad is arrested and tortured daily for a month. On the 18th of August, his body appears in the city square, hung from a lampost by the wrists, a placard around his waist listing "the sins of he who directed the site of idols". At his feet is his severed head with the black-rimmed glasses put carefully back in place. The most macabre of images.

The Koran contains various verses dealing with decapitation: “When you encounter an infidel, direct your blows at his neck until death occurs." [47:4]. We are by now well familiar with the idea that for a Muslim this is the most humiliating way to die. Resurrection, or an afterlife, is not possible if the victim's head has been forcibly removed.

This brutal story is barely 2 years old yet only a week ago, the Director-General of the Ministry of Antiquities for Syria confirmed: “Since then, we have buried 15 civil servants here: four were decapitated by ISIS and the rest were killed by either snipers or explosions." Extremist executioners are creating a new category of Syrian cultural heritage hero.

Palmyra before May 2015

In a small Italian city

Recently, in the sleepy Italian city of Aquilea 90 km east of Venice, there was a notable little exhibition: Portraits of Palmyra in Aquilea that deserves mention. It was the first ever in Europe dedicated to the ancient Syrian site since its destruction. Some 30 sculptures, photographs and mosaics were on display with a view to underlining and spreading the importance of a cultural heritage that is in danger. And all of it, from the inscription at the entrance to the walls painted the same shade of blue as Palmyra museum's, is in homage to Professor Al Assad. Aquilea, known as "the mother of Venice", could be said to have hosted, in its own right, an exhibition showcasing the 'Venice of the Desert'. Two cities, both declared World Heritage sites by UNESCO, who interact with each other despite geographical distances via these masterpieces of art. Perhaps this should be the mirror through which other projects or start-ups or groundswells should see themselves in a Europe that, for some time, has been losing and then refinding itself incessantly. Art as a unifying influence. Or a sticking plaster.

Tomb bas-relief with portraits of Batmalkû and Hairan, Palmiya, 3rd Century AD

Irreplaceable Treasure

Resonating amongst the works on display at the exhibition could be heard two intersecting voices: that of Paul Veyne and the 127 pages of voyage into the past in his Palmyra: The Irreplaceable Treasure (Ed. Ariel, 2017) followed by the muted voice of Al Assad: “The oasis of Palmyra - he wrote - appears in the distance, protected on the west and north sides by a mountain range with Jebel Haian as its summit. In the east and south, the city opens out into infinity. A garden of half a million olive, palm and pomegranate trees surround the ruins like a crown of laurel leaves. Golden columns, tombs and, especially, the imposing mass of the sanctuary of Bel ..." This city, whose arquaeological richness is comparable only to that of Pompeii or Epheseus, was a settlement from 2000 BC onwards and a melting pot for many civilisations before being annexed to the Roman Empire in the 1st century AD. It later reached its maximum expansion during the reign of the great Queen Xenobia. Palmyra was the crossroads on the old Silk Route. In the second century AD, Aramaic and Greek were spoken by merchants, travelling or resident, as commerce thrived ~ the Romans bought incense, pepper, ivory pearls and silks from Persia, India and Arabia in exchange for wheat, wine and oil. And it was certainly the case when examining the faces engraved on the tombs of Palmyra's most powerful families that there existed a certain analogy with other parts of the Roman Empire, as well as shades of the Oriental. A modernity similar to the eclecticism we see today on any Manhatten or Barcelona street, the one Veyne called "faces of the citizens of the world".

Explosions in Palmyra, May 2015 - March 2016

Palmyra, that fertile queen of the desert, represents everything the fanatics hate: openness, cultural interchange, the notion of a patrimony for all humankind ... With its eternal beauty, it challenged the dark ages of brutality and ignorance. It was in the hands of ISIS between May 2015 and March 2016. The Spanish artist Goya had already painted the destruction of art in a series drawing from 1814. Captioned "He knows not what he does", it shows an absurd-looking, bare-chested man, arrogant, his eyes closed, brick hammer in hand. He has just smashed a statue to pieces. It could be a contemporary image. Although iconoclasm has always existed, from Byzantium to the Reformation, from the Russian Revolution to Nazi Entartete Kunst 'degenerate art', we are nevertheless now witnessing a new type of terrorism. Jihad by media. The Taliban produced images whose global impact had been exceeded only by footage of planes hitting the Twin Towers. Since then, there has been no let-up in the internet spread of Islamic propoganda which goes to show just how difficult it is to control what is posted and the impact of electronic images such as the destruction of ancient manuscripts in Mali, heritage sites in Jorsabad, the Great Mosque Of Damascus and the Krak des Chevaliers in Syria, not to mention the van attack on the Ramblas in Barcelona and the threats concerning the Sagrada Familia cathedral there. Some days ago, leaders from the UK, France and Italy spearheaded a proposal that internet giants remove extremist ISIS content in less than 2 hours. Urgent measures are required. As Veyne so rightly said: "To know only one culture, one's own, means condemning oneself to living just one life, isolated form the world that surrounds us."

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

With a warm welcome, one of the most renowned painters of the American artistic scene opens the door of his house to us in New York’s West Village. Frank Stella (Massachusetts, USA, 1936), precursor of minimalism at the time when abstract expressionism led the artistic panorama, shows me the layout of the rooms in the museum where 300 of his works, dating from the end of the 50s until today, will comprise his next exhibition. Whilst holding dear the memory of the great retrospective through which the Whitney Museum of New York paid homage to him, today it is the NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale in Florida that will inaugurate, this November 12th, the exhibition which covers 60 years of his career. The artist invites me to take the elevator to the second floor, where after preparing a coffee, we evoke his life and trajectory.

Author: Elena Cué

Frank Stella en su casa del West Village, Manhattan. Photo: Elena Cué

With a warm welcome, one of the most renowned painters of the American artistic scene opens the door of his house to us in New York’s West Village. Frank Stella (Massachusetts, USA, 1936), precursor of minimalism at the time when abstract expressionism led the artistic panorama, shows me the layout of the rooms in the museum where 300 of his works, dating from the end of the 50s until today, will comprise his next exhibition. Whilst holding dear the memory of the great retrospective through which the Whitney Museum of New York paid homage to him, today it is the NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale in Florida that will inaugurate, this November 12th, the exhibition which covers 60 years of his career. The artist invites me to take the elevator to the second floor, where after preparing a coffee, we evoke his life and trajectory.

You were born between two World Wars, to a family of Italian inmigrants. What memories do you have from that time?

I have some strong memories due to of the war but mainly I remember right after it, when it was all about the destruction and rebuilding of Europe and America. It was a very fast-moving and dynamic period. There was a lot of real growth and an incredible optimism that nobody has seen since; it was amazing. In a way it was a very happy time, everybody was so glad the war was over that it created a kind of momentum to go on.

What was the start of your artistic life in the 50s when the scene was dominated by Jackson Pollock, Nauman, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschemberg...?

It was very active but at the same time very relaxed. There was a big change, not just in the art world but in general. I was just one of many young artists. I think partly because of the war, a lot of the European artists came to the US in the late 30’s and the American artists who were here benefited from that but the abstract expressionists were slightly older. Then there was a whole generation of younger artists who were supported, in a funny way, by the government because of the GI Bill. Americans could study in Europe funded by the government which created a bunch of artists. It lead to a combination of European artists coming here and Americans going to Europe and then coming back. There was a lot of activity and a lot of it was quite relaxed because people just made do with what they had in terms of money. It was possible for almost anyone to get a working space and to have enough work on the side in order to keep creating art. Everybody was working and exhibiting. There were exhibition opportunities, which means showing your work, and that’s what artists really care about. They like to get paid for their work but what really bothers them is to not have it seen.

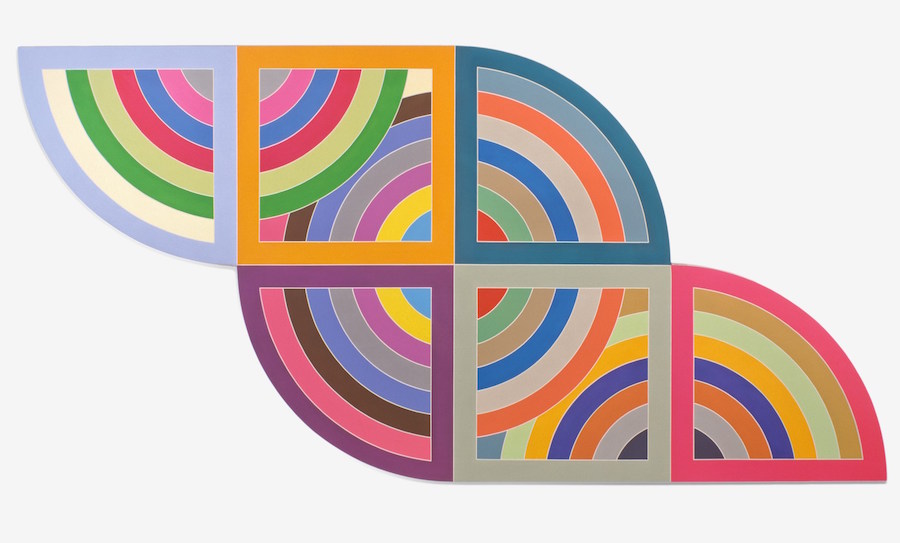

Frank Stella. Harran II

In this decade, when abstract expressionism, which profoundly shows the emotional dominated the artistic sphere, you opted for a more formalist art...

I think there is a slight misunderstanding. They said my paintings were less emotional but they were just trying to create a sense of organization, to build a structure that you feel you can work from, but I like the chaos. In a way, it was trying to find out what was under the chaos because the chaos of abstract expression is so powerful. I think to a certain extent it’s easy to see that underneath the painting that seemed so wild in America, was the structure of painting in Europe up until the late 30s, which was basically Cubism and Surrealism.

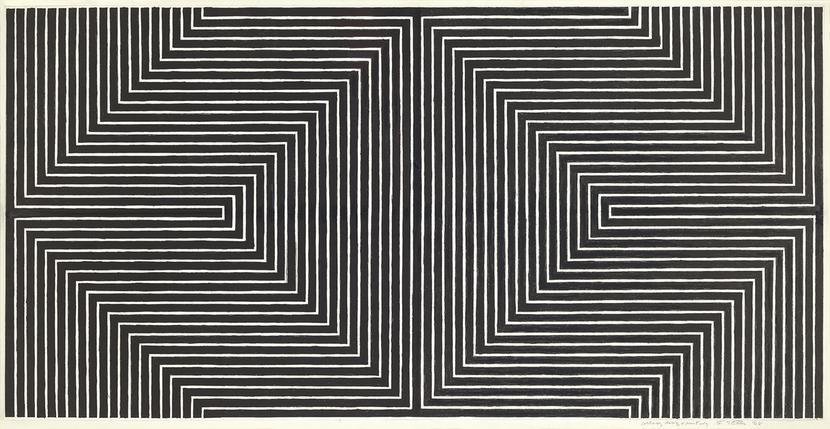

When you look back to where you began, to your Black Paintings from the 50s, what do you see?

I see two things, two paintings. The paintings just before the black ones which are kind of black and a lot of different things. And then I see that something happened and I decided to make it a little bit more symmetrical and organized. There are basically two parts to it: the part that is very much a version of abstract expressionism and then the part that is firmer and more organized.

Frank Stella (1968) Black Study

You started making black paintings in the 50s and in the 60s you introduced color, even florescent color...

I think it was inevitable. My father was the first one to say, “color sells”. You can get the same advice from almost every art dealer in the world. The critics are sometimes even more childish than the artists with ideas like “there is nowhere to go now, it’s all black”. I maybe repeat this too often but I think if you played my career backwards, so if we started from now as the beginning, played it back and ended with the black paintings, I think people would be a lot happier.

Your Irregular Polygons series (in the 60s) marked a turning point in your work. Can you explain why it was so important?

Like everything, there is always a large part created by accident. In general, abstract painting, which is what I wanted to do, is largely expressed in terms of what started with Mondrian and Malevich which is basically a form of geometric painting. The basic idea was that you had a flat surface and you made a geometric pattern, but usually the geometric patterns were dividing the space. I was looking for something that would still be a kind of geometry, but a geometry that was more dynamic or fluid and then something happened by accident. I focused on a Malevich painting that caught my attention, a well-known painting. It was a white ground, a black rectangle and there was simply a blue triangle laying on top of that black rectangle. I was thinking about it and then suddenly it struck me that what was interesting was that what most geometric paintings did was put one thing on top of another. And what I was looking for was making the triangle penetrate the rectangle so that you went around it and made a shaped canvas. It was as though you took the background away from the Mondrian and let the triangle and the black rectangle exist on the same plane. So it was a slightly different way of looking at the geometry but to me it actually seemed more dynamic and exciting and offered a lot of possibilities. It’s all Malevich’s fault.

Frank Stella. Irregular Polygons: “Ossipee II” (1966), “Chocorua IV” (1966), “Effingham IV” (1966) y “Moultonville I”I (1966)

In 1970, at 33 years old, the MoMA exhibited a retrospective of your work and your latest achievement was to receive the National Medal of Arts by President Barack Obama. How does this recognition affect your life and your work?

We talk about age and I’ve been lucky to live a long time. I was young when that happened and, if I were to explain with metaphor from the sports world I’d say, when you’re playing the game and you're in it, you don't really think much about it because you have to react to what’s going on and you just do the best you can. So in a way I didn’t really think too much about it. It was very exciting but I was just one of many artists who were relatively young and were experiencing really successful and exciting careers. We were all working so much, there were a lot of ideas around, a lot of things happening. After all, at the same time I had that exhibition you had color field painting, pop art, second generation abstract expressionism and that’s not to mention what was happening in sculpture with people like Michael Heizer, Richard Serra and Chamberlain. So there was so much going on that I never felt separated, I felt part of it. Before that retrospective, one of your black paintings was exhibited in the MoMA . There’s an interesting story about how they bought it. The head curator Alfred Barr liked it but he knew that it wasn't going to be popular with the board of trustees or the other curators. But Alfred Barr had a fund and was allowed to buy anything he wanted for the museum that was under one thousand dollars. I remember that Leo Castelli called me up and said that he was going to sell the painting “Marriage of Reason and Squalor” and we had agreed at the time for one thousand two hundred dollars but he was going to sell it to the museum for nine hundred. I said “I don’t want to do that, that's crazy. Why are we doing that?” To which he said “Frank, get it together, it's the Museum of Modern Art”. There was no way it would have gone there for any price except for the price that Alfred was able to buy it under his own stipend. It didn't just happen because they loved it so much.

Your Moby Dick series appears to be a obsession given that you dedicated, on and off, 10 years to it. What was it about Melville’s book that impacted you so much?

In some ways, I was reluctant to do it, but it had such an appeal to me for one main reason. Above and beyond the power and the beauty of the story and the incredible language of Melville, it is really a story of going around the world, about traveling and there was something about that, that to me, seemed to allow you an incredible kind of freedom. You can take plenty of time and it didn't all have to be the same. It allowed for the introduction of different ideas and different ways of thinking about things. It was really very open ended while at the same time it gave you a structure or outline to work with.

“And may God hunt us all if we do not hunt Moby Dick to the death!”. What do you consider to have been your impossible battle? Maybe with God...

I don't think I’ve had one. In modern times, the artists see themselves as having an incredible struggle against the difficulty of making art but that wasn’t always true. I grew up in a very straight forward way, in a Catholic American-Italian family and never worried about God. In fact, as I grew older I liked God because he had very good taste in art, at least in Italy. I found him to be a kindred figure.

Frank Stella, The Grand Armada (IRS-6, 1X), 1989. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen / Basel, Beyeler Collection. © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

You have used painting as an object. What does continuing to paint mean to you? Why don’t you do installations, performances, conceptual art…?

I make objects and I like to paint on them, one way or another. Actually, the problem with the printer and 3D works is that they get so complicated that it’s quite hard to paint them. I mean literally, in the sense that if you don’t tangle your fingers, it's hard to get in there and paint them. They do have spray paint so in the end you can get in there one way or another. It's a different way of working which for me changed with the Polish village paintings. They became constructions, an enlargement of collage in 3D. When they were made, I realized I was going to start building my paintings and then paint them. That's how it changed and now I just think that way. It’s not a new idea, a lot of people, such as Ron Davis, were doing things like that. I think in a way the shaped canvas lead to that. Once you gave up the regular rectangle, it was a little difficult to build the shape so there was more emphasis on the construction of what you were going to paint on.

At one point in your career your interest in architecture and sculpture grew, was this to the detriment of painting?

It’s not exactly to the detriment of painting. Using the Renaissance as a reference point, almost everybody that made art (at least during the Renaissance, and maybe even at all time) could do architecture and sculpture as well. I mean you can write music and you can also play the piano or the saxophone. But I must say that architecture did have an effect on me when I was younger. Frank Lloyd Wright was a big influence, I went to see his work and it was great. We had a very good library in the town that I grew up in by a famous 19th century American architect H.H. Richardson who had evolved a kind of Romanesque style in America.

Frank Stella. Project: K.304. Location: New York, USA. 2014

Where did your baroque style come from over the last few years?

I guess it is a change. For a while, it was minimalism and then maximalism. As the expression says, you throw in everything but the kitchen sink. It’s easier to add the ingredients but it’s not very programmatic. It’s about how things relate to each other and what the idea suggests. Sometimes, it is a problem for me and I do better when I take things away than when I add more.

How has art changed since Chauvet, Lascaux, or Altamira?

It has changed but I like the early art because it was very straight forward. The big idea was that you made what you saw, it was about observation. There is a lot of talk about the magic and the mystery but I think that is actually wrong. They didn’t have an idea about the development of art, they were trying to picture and live with what they saw. They could have made a lot of pictures of plants or trees for example, but instead they made them of animals because that was a big part of their life.

How do you see the art world now?

It’s an interesting version of what happened in the 60’s. It’s a little bit tricky because there are more artists and opportunities now than ever before. If you take a not-so-positive view of it you can say it has expanded, but is there better art? I don't know if it’s just loyalty to my generation or the way I grew up but I don’t see that the quality of art has expanded dramatically.

Frank Stella. Foto: Elena Cué

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

A few years ago, Bill Viola found himself with mental block as to how to portray an image of the Virgin Mary. This New York born artist, currently on exhibition in Bilbao, admitted: "I just couldn't figure it out. It flummoxed me ..." Despite his agnosticism and his knack of coming up with new ways to render other religious themes, the prospect of doing so with the Mother of God, and the weight of her infinite representations in art throughout history, shortcircuited the thinking of the artist who, nevertheless, did inaugurate his video-installation 'Mary' in the North Quire of St Paul's Cathedral, London in September 2016. Reflecting on Bill Viola has brought us to Lisbon's National Museum of Ancient Art, where the exhibition 'Madonna: Treasures of the Vatican Museums' reviews the iconography of Mary with over 70 works on display.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

Vitale da Bologna, Virgin of the Flagellants (1350), Vatican Pinacoteca

A few years ago, Bill Viola found himself with mental block as to how to portray an image of the Virgin Mary. This New York born artist, currently on exhibition in Bilbao, admitted: "I just couldn't figure it out. It flummoxed me ..." Despite his agnosticism and his knack of coming up with new ways to render other religious themes, the prospect of doing so with the Mother of God, and the weight of her infinite representations in art throughout history, shortcircuited the thinking of the artist who, nevertheless, did inaugurate his video-installation 'Mary' in the North Quire of St Paul's Cathedral, London in September 2016.

Reflecting on Bill Viola has brought us to Lisbon's National Museum of Ancient Art, where the exhibition 'Madonna: Treasures of the Vatican Museums' reviews the iconography of Mary with over 70 works on display. Divided into 8 rooms, all painted blue in honour of Fra Angelico's skies, these paintings, sculptures, drawings and tapestries taken from various Vatican Museums allow us to travel in time from the 4th century to the 20th. We are accompanied by José Alberto Seabra Carvalho, the exhibit's curator, who stops us in the first room to point out two marble low reliefs from the tomb of a child found near St Peter's in Rome. It was one of the earliest burials in the old basilica, built over the tomb of the eponymous apostle, in the epoque of Constantine. Despite its antiquity, approximately dated the year 325, the Virgin Mary's iconography appears clearly and precisely, in an Epiphany scene.

Although the cult of Mary precedes the Council of Ephesus and even the Edict of Milan (313), the representations of Mary in the catacombs prove that her image did not become widespread until the Church's hierarchy was consolidated by Theodosius and Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire towards the end of the 4th century. In this work, Mary is already depicted seated on a throne, as were the empresses before her, and this iconography would later reappear during the Byzantine Empire and later still in Royal European courts. Nevertheless, the relation between maternity and government was known 2,000 years before Christ, when in ancient Egypt, Isis was depicted ruling with her son Orus.

The proliferation of icons of divine maternity was promoted by both emperors and the clergy alike. And to this cult was also added a calender: in the 7th century, Mary's four liturgical Solemnities had already been established and continue to this day.

Fra Angelico, Virgin and Child with Saints Dominic and Catherine of Alexandria (1435), Vatican Museums

Room 2 is a display of the dialogue between 14th century Sienese painting - with its Byzantian leftovers and Madonnas dressed in gold-leaf - and the 20th. Chagall's Crucifixion (1943) confirms the core axis from Duccio to Dalí, as regards the depiction of the Virgin Mary. “All of the collections of European art are inevitably great collections of Christian art: after classical antiquity, Christianity has since then been the patron of European culture", concluded Gabriele Finaldi in the catalogue The Image of Christ (2000).

As well as this affirmation and the massive bibliography compiled over centuries, we would do well to imagine the complexities faced by Christian artists on trying to represent Mary. Deciding who or what she looked like when no testimony as to her physical appearance exist; how to portray the episodes of her life; how to convey her suffering. These abstract concepts are difficult enough, almost impossible even, to figure out in words, let alone in image form.

Orazio Gentileschi, Virgin With Child (1603), National Gallery of Ancient Art, Rome

There is a strange little Italian tablet in the exhibition entitled The Assumption of the Virgin, painted on black poplar wood around 1410 by the Siennese artist Taddeo di Bartolo. The scene takes place on Mount Zion where the apostles are crying over the flower-strewn tomb of Mary. Christ descends majestically from the clouds to kiss the hand of his mother and guide her on her journey's end to heaven. It's a wonderful, protective gesture full of tenderness and in sharp contrast to the syncretism of the rest of the scene. The most surprising thing, however, is the depiction of the physical separation happening between Mary's body and soul ~ the latter, behind her golden robe, painted as a monochrome silhouette with blue wings. What an odd and somewhat scary iconography. If the details surrounding these biblical events are unfamiliar to, say, non-Christian tourists viewing them, then what astonished reading might they give them? Moreover, according to the Apocryphal Gospels, Mary's immaculate body did not die but slept for three days before her ascent to heaven. And so we reflect again on the huge gaps in the teaching of our culture. What do the youth of Spain, untouched by these themes, think on seeing the Easter processions with weeping Virgin Mary statues paraded through the streets, their hearts pierced by swords. Or when, at the height of summer, all the shopping malls close in celebration of the Assumption of Our Lady. Perhaps it's similar to the frustration some of us feel when trying to decipher the reliefs on the walls of Angkor Wat or the Kufic caligraphy on the medallions at Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.

Rafael, Presentation In The Temple (1503), Predela del Retablo de los Oddi

The exhibition continues with great works by artists from Pinturicchio and Rafael to Van Dyck. Then to the Roman collection is added an extra treat ~ a final room, this time painted red, dedicated to some Italian works from Portuguese collections. Here are some very important pieces such as a Leonardo da Vinci drawing and an Adoration of the Magi by Tintoretto, of a similar calibre to those of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco.

Jacobo Tintoretto, Adoration of the Magi (1580-1590), Santo Tirso, Monastery of St Bento of Singeverga

Oriental Carpets And The Life Of The Virgin Mary

There is a secondary, though no less interesting, dimension to this exhibition. A singular look revisiting the world of thread- weaving: the textiles, fabrics, rugs, silks and tapestries that symbolise an exchange between East and West as well as between the decorative arts and their reflection in painting.

There are several fragments of 8th and 9th century silk brocade of, perhaps, Syrian origin on display. The link between these fabrics and their later Coptic versions signal an affinity between these five-thread silks and Near Eastern Christianity.

Nevertheless, it is the appearance of Oriental rugs in the Renaissance portrayals of the Virgin Mary or in scenes of her life that piques our interest here.

Gentile da Fabriano, Annunciation, (1425), Vatican Museums

Venice and its lakes were, in the 15th century, the gateway to the Orient. Its strong commercial ties with Constantinople prolonged an Eastern influence which lasted much longer there than in the rest of Italy. Also, luxury items such as hand-woven rugs (from Cairo and Damascus - controlled by the Mamelukes - Ottoman Turkey, Persia and India) were a great bargaining tool, 60 examples of which were gifted to Cardinal Wolsey in exchange for a license allowing Venetian merchants to export wine into England.

From the 13th century on, when Marco Polo declared those from Anatolia to be the world's finest, Oriental rugs were already in huge demand. So much so that they soon made their appearance in European painting. Their vivid colours and manifold, elaborate patterns were like a magnet for artists' paintbrushes. For a long time, and in the absence of any originals, these rugs were only seen through their depiction in paintings. Consequently, the better-known designs, with their medallions, arabesques and Boteh motifs were named after the artists who painted them: Lotto, Bellini, Crivelli, Membling and Holbein.

In his famous The Visitation (1504), Vittore Carpaccio sets the embrace between Mary and her cousin Elizabeth in an idealised version of his natal Venice, a Venice festooned for a Feast Day, its balconies and marble palaces draped with Oriental rugs. Only those rich enough to afford them displayed them as decoration outside their homes. A fact that, also, demonstrates the 'melting pot' that was Venice at the time: a city whose patron, St Mark, had been "stolen" from the Middle East; a city whose great Arsenal went by the Arabic name "dar sina'a" meaning 'House of Manufacture; and a city where, notably, Muslim prayer mats were painted on the ground beneath the feet of Christian divinities.

Vittore Carpaccio, Visitation (1504), Ca' d'Oro, Venice

We continue on our "thread trail" with more paintings. In his The Virgin of Humility (1435), Stefano di Giovanni - called Il Sassetta - paints his Madonna seated on a rug of the "Lotto" style and this fabric is clearly marking out a sacred space. Also, Gentile da Fabriano's Annunciation (1425) and Sano di Pietro's Scenes From The Life Of The Virgin (1438). At that time, with the exception of rare examples such as Jan van Eyck's The Arnolfini Portrait, these rugs were never placed on the floor since only the feet of a saint or a king could aspire to tread on them.

Stefano di Giovanni - called Il Sassetta - Virgin of Humility (1435), Vatican Museums

Now at the end of our double tour of the Madonnas on display, we make our way to the gardens of this 17th century palace on the river Tagus. On leaving, an image from the museum's permanent collection catches our eye, namely the imposing Saint Augustine by Piero della Francesca (1460-70). This bishop of the Church, with his austere, blank stare and his white gloved and bejewelled hands holding a crystal quartz crozier, wears a chasuble that is richly embroidered with scenes from the life of Mary. Again, a Nativity scene, the flight from Egypt ... and again, what on earth must the Vietnamese tourist beside us be thinking? His eyes are fixed on the Annunciation scene where a winged being holding a flower branch faces a kneeling woman whose abdomen is traversed by a beam of light? Wasn't it Marc Chagall, of Belarusian descent, who said: "The Bible is the greatest source of poetry of all time".

Marc Chagall, The Crucifix (Between God and the Devil), 1943, Vatican Museums

Madonna: Treasures of the Vatican Museums

National Museum of Ancient Art

Rua das Janelas Verdes 1249, Lisboa

Curators: José Alberto Seabra Carvalho & Alessandra Rodolfo

May - September 2017

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

This is the story of a 21st century Iranian woman and a 19th century Spanish man meeting together in the Prado Museum, Madrid. The East/West frontier and the 200 years that separate them dissolve through the use of imagery, a means of expression first used by Goya and then by Farideh Lashai so as to denounce the dramas surrounding them: fratricidal wars, the cruelty of and between men, torture. Goya initiated the road towards modernity with a new but eternal message challenging injustice and Farideh, in re-envisioning his "Disasters of War", makes that message her own. Along with the recent anniversary celebration of Picasso's "Guernica" in Madrid, the works of both Goya and Farideh would seem to join their voices to his in a communal scream.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

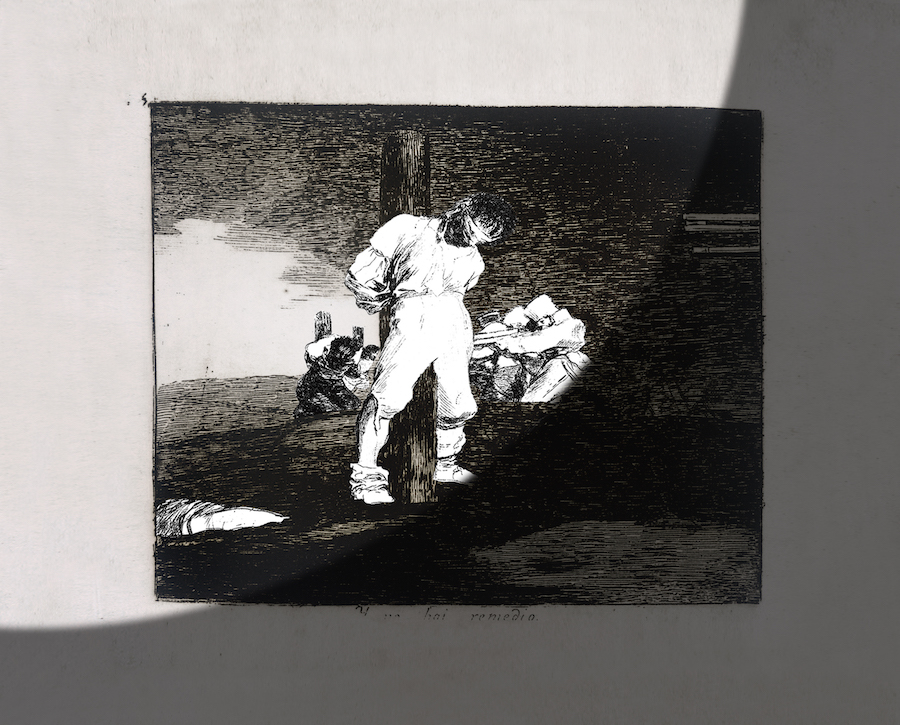

Detail: "And there's nothing to be done" from When I count, there are only you ... but when I look, there is only a shadow. Farideh Lashai. British Museum, London

This is the story of a 21st century Iranian woman and a 19th century Spanish man meeting together in the Prado Museum, Madrid. The East/West frontier and the 200 years that separate them dissolve through the use of imagery, a means of expression first used by Goya and then by Farideh Lashai so as to denounce the dramas surrounding them: fratricidal wars, the cruelty of and between men, torture. Goya initiated the road towards modernity with a new but eternal message challenging injustice and Farideh, in re-envisioning his "Disasters of War", makes that message her own. Along with the recent anniversary celebration of Picasso's "Guernica" in Madrid, the works of both Goya and Farideh would seem to join their voices to his in a communal scream. The lives of Goya y Farideh are entwined by several parallels: Goya lived through the Napoleonic invasion of Spain while Farideh was witness to events in modern Iranian history; from the arrival of Mohamed Mosaddeq, to that of Shah Reza Pahlevi, as well as the Iran - Iraq war. Both suffered voluntary exile and both sought refuge in art during illness and introspection at the end of their lives. This is, essentially, the story of an obsession ~ that of Farideh with the works of Goya.

Some of Chopin's "Nocturnes" should only ever be played senza tempo, allowing the melody, as if it were an anxious human voice unable to escape, to flow around us in waves that encircle and imbue us. Farideh Lashai's Nocturne emits from the piece it accompanies and lodges in the walls and floors of this little room in the Prado, forcing us to view Goya's "Black Paintings", the "Executions Of The 3rd Of May 1808" and "The Charge of the Mamelukes" on either side of it, in a completely different light. And it is here in this little room between them that Farideh Lashai has been invited to exhibit her "When I count, there are only you ... but when I look, there is only a shadow", an exhibition sponsored by the Friends of the Museum Foundation. The work, previously on show in the Museum of Ghant and continuing on later to the British Museum which is its current owner, will never again experience such an exceptional setting. Goya's "Black Paintings" will never leave Spain. For this reason, before leaving for Bilbao Fine Arts Museum, the Prado's director Miguel Zugaza thought it only proper for Farideh's work to be positioned here in amongst them, endowing them with a sense of the far-off and at the same time, embellishing them with a light different to that of the lantern illuminating the white shirt of the man about to be shot in "The 3rd Of May".

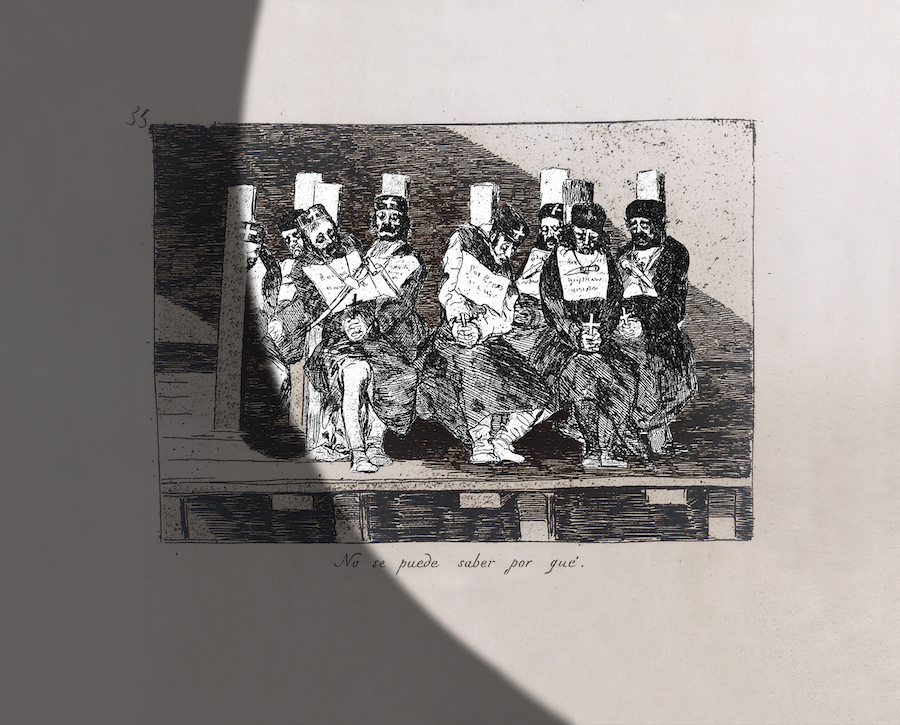

Detail: "Against the common good" from When I count, there are only you ... but when I look, there is only a shadow. Farideh Lashai. British Museum, London

"When I count ..." (2012-13), based on a T. S. Eliot poem, is the title of Farideh's latest work. Not at all surprising in that poetry is known as the bride of Persian literature, or that gardens were said to have grown on the Zagros mountains in the Iranian plateau, and lyrical poetry was a way of life for Farideh(1944-2013), one of Iran's most important contemporary artists. For this alchemist of sculpture, painting and stained glass design, writing was her backbone: "I lived in the city of Rasht until I was six. Those first few years left a strange mark on me. In the end, the place someone's born is like their mother: we're united by a primordial bond", she says in her autobiography "Shal Bamu". Whilst still a young woman, she travelled to Germany and studied at Frankfurt University where she found herself profoundly influenced by the works of Bertolt Brecht, at least six of whose books she translated into Farsi, as well as other works by Ginzburg. On her return to Tehran, she was arrested and imprisoned for three years in Qasr jail. Farideh knew no rules.

The exquisite text of the catalogue written by Ana Martínez de Aguilar, who curates the exhibition and who also translated the artist's autobiography from Farsi to Spanish, is entitled "I guard everything within myself". This phrase sums up the character and life of a nomadic woman who travelled to and from Persia from the rest of the world. In her book, written as a stream of consciousness, Farideh allows jumbled memories to flow from her childhood, surrounded by an earthly paradise of forest, sea and mountain ranges, through mystical Iranian poetry and on to political chaos. These leaps into the void mingle with her own memories, those of her mother and those of her grandmother. It's a matrilineal story in a patrilineal context that reflects personal and political life in the Iran of the 20th and early 21st centuries. All this pieced together with written words, painted words, layers of paint, and more words because as Farideh always said: "The joy that writing gave me was enough. To be able to capture a moment in words. To write meant images emerging like in a painting. In fact, I painted moments in time ... a dash of colour here followed by another there, or overlayed, in the same way that images follow one after the other from the written word. The synthesis of my work now turns out to be in the form of a collage."

This way of painting in layers came to fruition 7 years before her death when, already diagnosed with cancer, she began to use video-installations. This was her way of both avoiding the smell of oil paint whilst, at the same time, formulating a more complete message: to a still canvas she added movement, music and narration.

Detail: "Impossible to know why" from When I count, there are only you ... but when I look, there is only a shadow. Farideh Lashai. British Museum, London

For "When I count ...", Farideh takes Goya's "Disasters of War" series and manipulates it by removing every character from every scene. Men, women and children disappear, leaving only empty scenery, as in "A heap of broken images, where the sun beats" from Eliot's "The Waste Land". The original prints are no longer recognisable. They are now something else, something transformed into what could be the nondescript background to any other scene of desolation. There only remain ruins, scorched trees and lonely hills. It was Bertolt Brecht who first remarked on Goya's empty landscapes and this resonated strongly with Farideh who returned to the theme when, in the very last days of her life, she sees photographs and film of the outbreak of the Arab Spring.

Farideh scanned the figures and transferred them to digital film. The new photogravures are arranged in a rectangular pattern comprising 80 of the 82 prints from Goya's original series. The empty landscapes come to life as a moving beam of light, much like a theatre spotlight, is projected over each "Disaster", adding in the figures and animating them for a couple of seconds. The effect is magical and the influence, once again, of Brecht is palpable, as is that of Chinese and Iranian theatre, albeit from further away.

Detail: "And they too are fierce" from When I count, there are only you ... but when I look, there is only a shadow. Farideh Lashai. British Museum, London

Farideh's entire oeuvre is loaded with subtlety, including time lapses: the mere 2 seconds that each print is illuminated is long enough to have impact while still allowing us to blink and put the horror we are seeing into some kind of context. The beam illuminates the cruelty which then disappears into shadow while the spotlight continues on to the next scene. This less frenetic rhythm, this more intermittent repetition comes, perhaps, from Persia where the appearance and disappearance of history's most terrible moments forms part of its culture. In western cultures, our forced saturation in violent images by the media has anaesthetised our ability to take in the true horror of a car bomb in Kabul or the effect of shrapnel on a child's body, as happened in Manchester. Thanks to this distinct rhythm, Farideh re-educates our vision, makes us ask ourselves questions and insists on leaving us to ourselves, even when the light goes out: "Video meant a bridge to literature and offered me enormous scope for expressing myself. It brings something unexpected to my painting and creates a sensation of surprise. Also, when the video stops, the nature of the painting will have acquired a different meaning." And this sensation is so real that, after contemplating her work for a while, we walk to Goya's "Black Paintings" where the late Farideh's intentions are fulfilled. In "Fight To The Death With Clubs", our eyes don't just remain transfixed by the fight between two men, rather they travel down to the mud covering them up to their knees and the sky, ominous with clouds.

Among all her early travels, Farideh Lashai felt the need to be in Spain and pay a visit to the Royal Chapel of St Anthony of La Florida. This is what she wrote of it: "Goya's tomb was simple, seemly and sad - a rectangular slab of stone and a bunch of flowers beneath the dome of frescoes he himself painted. One of Franco's soldiers stood guard at the iron railings and I thought about who was resting in peace under that cold stone, about the man who was part of a revolution."

{youtube}PE8gx3om_SY|900|600{/youtube}

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

Farideh Lashai

When I count, there are only you ... but when I look, there is only shadow

A work invited to the Prado Museum

Paseo del Prado

Curator: Ana Martínez de Aguilar

Until 10 September 2017

Farideh Lashai

Between the motion And the act Falls the Shadow

Edward Tyler Nahem Fine Art

Calle Sánchez Bustillo 7, Madrid

Curator: Paloma Martín Llopis

23 June - 13 July 2017

- Broken Images: Goya and Farideh Lashai - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

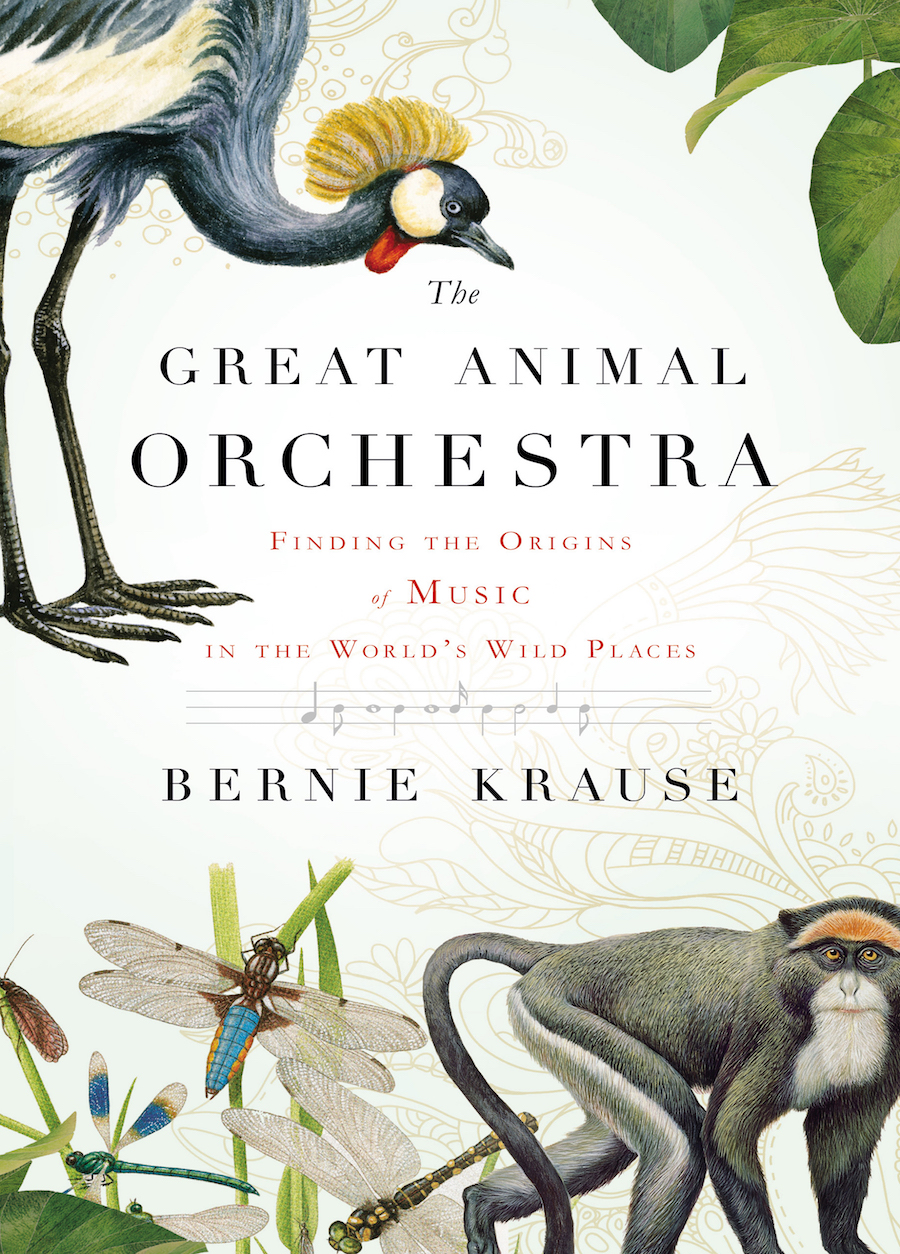

At least that is what the musician, scientist, naturalist and author of the book "The Great Animal Orchestra” (Detroit, Michigan, 1938), Bernie Krause, thinks. He wrote this book to show people that animals taught us to dance and sing and that soundscapes, particularly biophony and geophony, terms coined by the ecologist, have exercised a decisive influence on our culture.mKrause was a member of the famous American folk group The Weavers. When it broke up, he formed the electronic music duo Beaver & Krause. They introduced the synthesizer into pop music in the 1960s, playing in sessions for musicians such as George Harrison, Mick Jagger, Quincy Jones and Barbra Streisand, among others.

Author: Elena Cué

Bernie Krause in St. Vincent’s Island, Florida (2001). By Tim Chapman.

"The truth is the Greek myth got it wrong. It wasn't Orpheus who taught music to the animals, but the reverse". At least that is what the musician, scientist, naturalist and author of the book "The Great Animal Orchestra” (Detroit, Michigan, 1938), Bernie Krause, thinks. He wrote this book to show people that animals taught us to dance and sing and that soundscapes, particularly biophony and geophony, terms coined by the ecologist, have exercised a decisive influence on our culture.

Krause was a member of the famous American folk group The Weavers. When it broke up, he formed the electronic music duo Beaver & Krause. They introduced the synthesizer into pop music in the 1960s, playing in sessions for musicians such as George Harrison, Mick Jagger, Quincy Jones and Barbra Streisand, among others. At the same time, the also worked in film, playing music in over 100 big movies, such as Apocalypse Now and Love Story. For over four decades now, Krause has traveled the world conducting a bio-acoustic study, recording and documenting natural soundscapes. He has archived the sound of over 15,000 species, over half of which have already become extinct on account of man's interference with nature. This material consists of over 5,000 hours of recordings of the sounds of nature.

After a lifetime dedicated to music and sound, what does music mean to you? How would you define it?

Because I don’t see very well, my world has always been informed by what I hear. As a young child, I was first drawn to the sounds of classical violin and composition. In my teens, I switched to guitar and learned all styles. But when I applied to American music schools in the mid-50s with guitar as my major, I was told by the interviewing professors that guitar was not a musical instrument. Shortly after university, I joined, The Weavers. After The Weavers broke up in early 1964. During that period Jac Holzman, then President of Elektra Records, introduced me to Paul Beaver. Together we formed Beaver & Krause. As a duo we introduced the synthesizer to pop music and film on the West Coast and the UK.

Paul and I realized that with the introduction of the synthesizer to musical composition, the standard definition(s) of music had also changed. So we re-defined music as the control of sound. That definition has held true even for the sound design and compositions I and colleagues have rendered since I helped initiate the field of Soundscape Ecology.

Where do you think is the common ground between the sounds of the natural world and music created by Man?

When we lived more closely connected to the natural world, we mimicked the sounds we heard coming from the forests and plains that comprised the environments in which we lived. These expressions included rhythm, melody, harmony, texture, and the structure of sound (composition). By observing the animals move, we copied their journey through space and learned to dance. In North America, there are still Native American tribes that perform a deer dance, or a bear dance, or an eagle dance…all based on an ancient need to show deference to the living world that surrounds and sustains us.

Dian Fossey’s Rwandan research camp (1967), Karisoke. By Nick Nichols, National Geographic

You have recorded more than 5,000 hours of sounds from different habitats, both marine and land, and more than 15,000 animal species. What are the greatest changes you have noticed over these five decades?

Sadly, the greatest change is the overwhelming loss of density and diversity of species almost everywhere I go these days. In some places, like northern California, where I and my wife, Katherine, live, we experienced the first completely silent spring (2015) I can ever remember in the nearly 80 years of my life. There were many birds, but they weren’t singing; it was the fifth year of the historic drought that descended on our section of the continent. The biophony (collective sound produced by all organisms in a particular habitat) returned to some degree this season likely because of the significant amount of rain we had this past winter, extremes of weather that are most likely a direct consequence of a drastically changing climate.

With so many years of experience observing these climate changes...

I should also point out that as a consequence of these climate shifts, resource extraction and land transformation, well over 50% of my natural sound archive, recorded since 1968, comes from habitats that are now either altogether silent, or where the biophonies can no longer be heard in any of their original form. For the past 25 years I have been seeking an academic home for this precious archive. It contains soundscapes most of us will never experience in the wild, again.

Then, do you defend the theory that climate change is caused by human activity or do you think that, despite the consequences of the obvious increase in CO2, the natural climate cycles are more relevant?

Based on the science I’ve read, and the many trips to remote places I’ve visited on the planet, I can imagine no other explanation for what is transpiring everywhere. We are a stubborn, illiterate, selfish, and greedy lot. And as long as we are driven to consume at the rate we do, with no limits on the degree of our avarice, my optimism fades. I’m still hopeful. Just not optimistic.

And, what do you think has contributed more to the disappearance of species: noise, pollution…?

Species disappear mostly because of our unbridled need to exploit the remaining resources of the earth for objects we simply don’t need. It is justified in many quarters by biblical mandates that have always been short-sighted and pathological to begin with. Those unfortunate echoes guide us even and especially today, despite all of the evidence screaming at us to cool it if it is our intent to thrive.

What is our culture losing by distancing itself from natural sounds?

In the end, before the forest echoes die, we may want to listen very carefully to the diminished but remaining voices of our world. We’ll quickly discover that we humans are not separate. Instead, we’re a vital part of one fragile biome.

How many of us will hear the message in time?

The whisper of every leaf and creature implores us to cherish the living world around us – which, indeed, may hold secrets of love for all things, especially our own humanity. This divine music is fast growing dim; the time approaches when we may have to bear witness as the creature spirits return for one final hunt.

What is the sound that has made the greatest impression on you?

It is actually a class of sound called the dawn chorus. Each spring season, in still-healthy regions of the world, birds tend to populate biomes in large numbers, competing not only for physical territory and mates through their extraordinary songs, but also for acoustic turf. The organization of these collective voices, which, by the way, also include insects, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals, is called the biophony. Graphic illustrations of these biophonies are called spectrograms. And when the soundscapes are healthy, the spectrograms look much like a contemporary musical score. The collective voices of these organisms evolve to occupy special niches so that they stay out of each others’ way. Otherwise their voices would be masked. And if their vocal behaviour developed to help these organisms survive, then the signals need to be clearly heard. That, I suppose, is not only my favourite and most important discovery, but it has also made the greatest impression on me. I am amazed every time I visit one of these great places and hear a healthy biophony.

Entonces, segun usted, Are animals able to synchronise their sounds like a large orchestra?

Yes. They have to. Otherwise, there would be bioacoustic chaos. These organisms have evolved to synchronize rhythm, melody, and even arrange their voices in counterpoint. The ways in which their voices coalesce in layers and textures is a form of synchronization. This can be heard in the way chimpanzees and the other great ape species beat out complex rhythms on the buttresses of ficus trees. In the way that frogs and insects synchronize their voices when chorusing.

What would you recommend in order to improve the knowledge and care of the various marine and land habitats?

I guess we need to learn to shut the hell up and get our priorities focused in order to pro-actively protect what remains of life around us.

Through your organization, Wild Sanctuary, you recorded bio-acoustic albums. These recordings have also been used to create interactive environments in museums. Could you explain what this relationship with museums is like?

When I changed careers from music to science in the late 1970s, it soon became clear to me that the publication of scientific papers, alone, meant that only a few people would ever see or hear the results of this work. So, like a few of my valiant colleagues, I decided to reach out to a larger audience through my craft and art.

After the publication of my book, The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World’s Wild Places, in French translation, Hervé Chandes, Director at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art Contemporain in Paris, contacted me in late 2015. After several encouraging exchanges he commissioned me to create a work of sound art that, instead of performing like background music, would serve as the focus of an entire exhibit and where the visual components would be informed by the sound sculptures. This was a very risky enterprise because there was no precedent on that scale and because every component of the exhibition was imagined, designed and realized literally from nothing. The installation, titled Le Grand Orchestre des Animaux, ran from early July, 2016 to January, 2017 and was one of their all-time most popular exhibitions.

You converts music into art sculpture

It is important to note that sound is not taken very seriously in western culture because we’re primarily visually oriented with most everything that informs us predicated on what we see. This exhibition changed that equation for the first time. The shadow sense (sound), is no longer ephemeral. It has finally found a fragile but seminal place in the hierarchy of the senses and thus, the fine arts.

For me, this experience has been utterly exhilarating. I had become profoundly depressed by what has been occurring in my own country, not only a dismissal of the value of the arts, but also the sciences. And I felt a deep sense of despair. With Chandes’ call and commission, and being able to work with such a dedicated and fabulous group of young people at the Fondation, I felt for the first time in a long while, a real sense of hope.

Bernie Krause in St. Vincent’s Island, Florida (2001). By Tim Chapman.

Bernie Krause: The voice of the natural world

- Bernie Krause: We need to learn to shut up and actively protect our environment" - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

This may not be art criticism as such, coming as it does in the final days of an exhibition, but it may rather be the question: What will remain after its close? What mark will it leave behind? The Anselm Kiefer retrospective at the Pompidou Centre in Paris will end in a few weeks and all that will be left of the 150 monumental paintings and 40 glass display cases is the question: What happens after Kiefer? It will not be easy for the artistic panorama of the next few years to match the impact of this exhibition. The density of his ashy, cloudy paint remains suspended, living, floating above the Parisian skyline on the sixth floor of the museum. It would seem almost as if the walls of various galleries in the Pompidou have had to be specially reinforced to accommodate the sheer size of these colossal paintings.

|

Autor Colaborador: Marina Valcárcel

Licenciada en historia del Arte

|

|

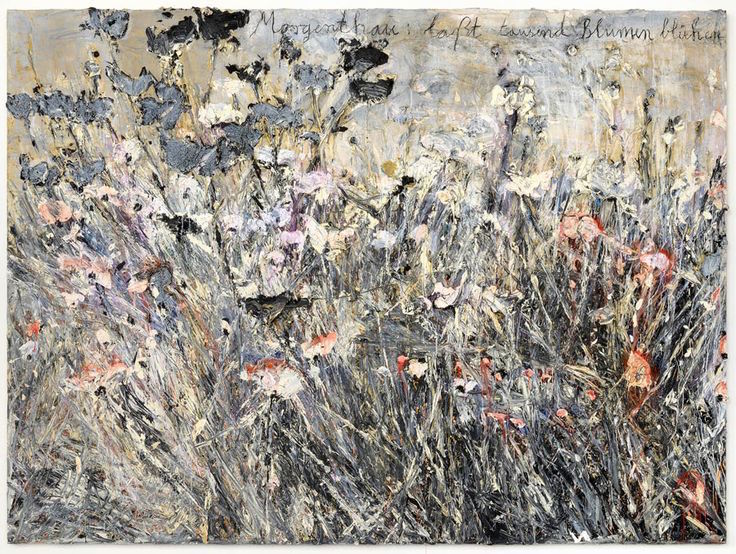

Der Morgenthau Plan (The Morgenthau Plan), 2014

This may not be art criticism as such, coming as it does in the final days of an exhibition, but it may rather be the question: What will remain after its close? What mark will it leave behind?

The Anselm Kiefer retrospective at the Pompidou Centre in Paris will end in a few weeks and all that will be left of the 150 monumental paintings and 40 glass display cases is the question: What happens after Kiefer? It will not be easy for the artistic panorama of the next few years to match the impact of this exhibition. The density of his ashy, cloudy paint remains suspended, living, floating above the Parisian skyline on the sixth floor of the museum.

It would seem almost as if the walls of various galleries in the Pompidou have had to be specially reinforced to accommodate the sheer size of these colossal paintings. Some are of the insides of claustrophobic, totalitarian architectures; some are of snow-covered, bloodstained forests; some are of serpent-strewn pathways named after battles such as Teutoburgo, Varus ... And then there are Kiefer's landscapes: arid, divvied up into motley wrinkles as if they were traintracks leading to cremation ovens, converging into a one-dimensional escape route towards a flattened horizon and a sky that doesn't exist. These are the denunciations of a German artist seeking to make some noise in a world of silence.

Varus, 1976

Anselm Kiefer was born in May 1945 in Donaueschingen, a part of the future Federal Republic of Germany, and belongs to that second generation of Germans who grew up without reference to or memories of the Nazi regime. Those were years in which the country's authorities anaesthetised the entire population in an attempt to avoid any sense of responsibility or culpability for the Holocaust and when a layer of charcoal was thrown over the whole of German tradition and its Nazi past to destroy any recollection thereof. Kiefer was born after Auschwitz but wants to live alongside Auschwitz. This is why, after 1970, his work becomes what Daniel Arasse calls "a theatre for memory": to rescue, restructure and represent German identity. From that moment on, Kiefer's mental imaginings become wholly dedicated to the creation of a contemporary version of historical painting.

At this moment, the Pompidou's white ceiling appears lower than is customary, drawn down and diminished by the sheer height of Kiefer's paintings and by the concrete flooring that makes the uniquely artificial light shine like steel. Even the gallery housing the glass display cases is somewhat suffocating, each one squeezed beside the next as if in a dusty old Natural Sciences museum. These object displays are the fruit of Kiefer's accumulation of what he calls the catacombs of his Barjac studio: objects waiting to be converted into messages: pieces of clay, spools of charred film, old typewriters, fossils, twisted lamps and dried flowers. Nothing is thrown away, every material thing has a life, everything is recycled within or into another painting or another sculpture.

Saturn-Zeit (The Time Of Saturn), 2015

Kiefer excites our sensorial curiosity. And he does so with his pictorial technique: from his choice of materials to the stratification in layer upon layer of them onto a picture painted over what could be any length of time: "My paintings might be compared with the Talmud, with their commentary on commentary, their sedimentation on siltation. If one made a hole in the canvas, the whole history of the painting would be visible, vertically", says Kiefer, who challenges us through the materials, the colours and the condition of his paintings. From the 90's onwards, his works, encrusted with paint, have been much more than just an image. They are, rather, a journey over deep, rough and uneven terrain that invite us and our puzzled senses to familiarise ourselves with them, to touch the unknown, to feel, to scratch, to smell them almost.

Anselm Kiefer's paintings are not easily approachable, the spectator having to put distance between himself and them by moving away and thereby finding himself looking at completely different dimensions. Kiefer's works since 1980 have aquired titanic proportions perhaps because history is a construction that can't easily be assimilated. All of Kiefer's art impacts us. And this initial impact is to do with the world of sensations, not just that of dimensions. It is an arbitrary division of aesthetic philosophy, Kiefer belonging more to the realm of the sublime than the realm of beauty. Kiefer's work seizes the spectator, obliges her to steel herself, infects her with anxiety and perplexity but also with curiosity. In this sense, Kiefer puts up the same barriers as a German Romantic would. We feel the immensity and vastness of Wagner's Ring Cycle and its tragedy. It also takes us towards solitude, doubt and the same question asked by Caspar David Friedrich's subject, the man wearing a black dress-coat leaning on his walking stick, his back to us facing faraway mountains: The Wanderer Above A Sea Of Fog (1818).

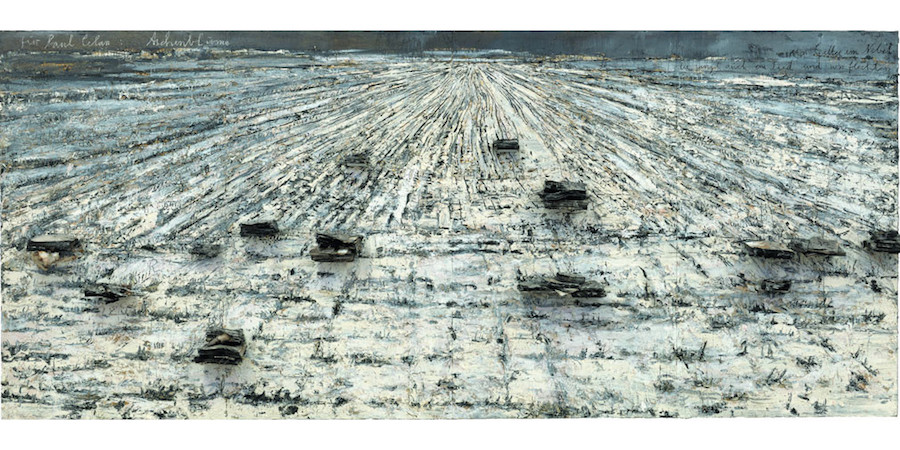

Anselm Kiefer is an all-round artist: painter, sculptor and creator of installation spaces but also, and especially, he is an artisan: blacksmith, miner, carpinter and a landscaper artist living with an intense interior discourse: "My biography is the biography of Germany" he says, but it is also the history of the Jews, Shoah, Kabbala, The Song of Songs, Germanic myths, alchemy and the cosmic vision of Robert Fludd: every heavenly body has its counterpart in a flower. And books, his library: Heidegger, Walter Benjamin, Hölderlin, then Ingeborg Bachmann and after her, Paul Celan. And after Paul Celan, more Paul Celan. Paul Celan has been deeply imbedded in Kiefer's paintings since 1980 . The latter is a German painter who takes on his country's past by unearthing the Holocaust and who always wanted to be a poet, the former a renowned Jewish-Romanian poet of the latter half of the 20th century who chose to write the poetry that burned inside him in German, the language of his tormentors.

Is it possible to write poetry after Auschwitz? asks Theodor Adorno. Perhaps there's only room for silence. But if one chooses the route of not being silent, if one wants to continue to denounce in German, it then becomes necessary to refound that language. For this reason, Celan uses language somewhat secretively. And so, from this union between painter and poet, come entire verses written in Kiefer's looping, joined-up letters, words emerging from black skies to live on in the paintings. And their titles: "For Paul Celan: Ash Flower", because flowers and Celan come together many times in Kiefer's work.

Für Paul Celan: Aschenblume (For Paul Celan: Ash Flower), 2006

"Your Golden Hair, Margarethe" is a 1981 painting inspired by Celan's poem "Death Fugue". Kiefer paints, sticks and scratches strange flower-like blades of straw that emerge from the black ground like rays of light tipped with a pink flame. These are Margarethe, representing the German nation with her long golden hair and Shulamith with her burnt, ashen hair representing the Jewish people. These icons of Celan's poetry are represented also in the materials used: straw, ash, hair, sand ... As if the written words themselves had melted onto the surface of the paint.

Your Golden Hair, Margarethe, 1981

We continue on through the Pompidou. Suddenly and unexpectedly, we enter a different room altogether that is bright, light and flooded with sun and colour. And, we think, cheeriness. There are only four large-scale paintings of flowers here. Why is Kiefer painting flowers? Why has he started planting field-fulls of sunflowers in Barjac where he has his studio? Why are sunflowers gradually invading his paintings and sculptures? Kiefer is once again using painting to challenge and question history. Towards 2010, Kiefer turns to something that happened in the final days of the Second World War ~ The Morgenthau Plan. In order to prevent a post-war Germany from developing a programme of heavy industry and to thwart the threat of her re-arming, the US Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenenthau, proposed a radical plan to the international authorities which involved converting Germany into a primarily agricultural and pastoral country. Kiefer imagined the enforcement of this plan by painting pictures bulging with carpets of colourful blooms, lets himself get carried away by their beauty, covers his canvases in thick layers of acrylic paint from which emerge soft multi-hued shapes which remind us of Kiefer's devotion to Van Gogh's painting. He called it "The Morgenthau Plan".

Der Morgenthau Plan (The Morgenthau Plan), 2014.

On the opposite wall is "Lilith" (1987 - 1990). Since his visit to Israel in 1984, Kiefer's paintings have been heavily influenced by the Kabbalah (developed in the 16th century by Isaac Louria), the Bible and various rabbinic texts. Lilith was Adam's first wife before Eve in Jewish mythology and she personifies envy, jealousy and the desire for revenge. She is the serpent in the Garden of Eden. The painting, inspired by Kiefer's visit to Sao Paulo in Brazil, shows an apocalyptical city covered in ash. In the centre hangs a long lock of black hair that symbolizes Lilith. The rest of the painting appears studded with dried poppy stalks that leap out of the canvas at us. Again and again there is reference to Paul Celan, one of whose earliest poetry collections was entitled "Poppy and Memory", poppies being the symbol of both forgetting and remembrance.

Lilith, 1987-1990.

According to the Scriptures, all who are buried in Israeli soil return to life. The scholars of Judaism say that the land of Israel has the power to expiate, to forgive sins. Paul Celan committed suicide aged 48 by drowning in the Seine, Paris. He is buried in the unassuming Thiais cementery on the outskirts of Paris. His plain tombstone is grey, identical to most of the others but covered in little stones. This is how Jews leave a sign that they have visited their dead loved ones. Because flowers belong to life.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Anselm Kiefer, las flores y la poesía de Paul Celan - - Página principal: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

As we approach the High Altar of St Paul's Cathedral in London, sunlight floods through the two great windows on either side. The glass is neither stained nor tinted, just crystal clear. We walk slowly here, amazed by the pomp and colossal size of Wren's cathedral, perhaps a little disoriented by its resemblance to St Peter's Basilica in the Vatican City with its baldachin, its Solomon's Temple-like columns, its sheer dimensions and its profusion of marble. But here there is an electricity distinct from that of Rome. Nelson is buried beneath our feet, as is Wellington. There are flags from old military campaigns, memorials and, more importantly, there is contemporary art. Staggering present-day pieces that speak to us of current conflicts and originate from all over the world.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

As we approach the High Altar of St Paul's Cathedral in London, sunlight floods through the two great windows on either side. The glass is neither stained nor tinted, just crystal clear. We walk slowly here, amazed by the pomp and colossal size of Wren's cathedral, perhaps a little disoriented by its resemblance to St Peter's Basilica in the Vatican City with its baldachin, its Solomon's Temple-like columns, its sheer dimensions and its profusion of marble. But here there is an electricity distinct from that of Rome. Nelson is buried beneath our feet, as is Wellington. There are flags from old military campaigns, memorials and, more importantly, there is contemporary art. Staggering present-day pieces that speak to us of current conflicts and originate from all over the world. There is a Virgin Mary in a refugee camp by the graffiti artist CBloxx, two gigantic white crosses by the Indian artist Gerry Judah hanging from the central nave ... Different languages in a powerful crossover between the Baroque and the ultra-contemporary. My companion and I think of Spain. We expect something with a bit more rage to it, something more challenging, something to be overcome. We think of Burgos, Leon, Toledo and others, with their cathedral choir stalls, their altar railings. Bill Viola began working in Gothic churches to reflect their sound, that opaque silence that scales their pillars to the heavens ...

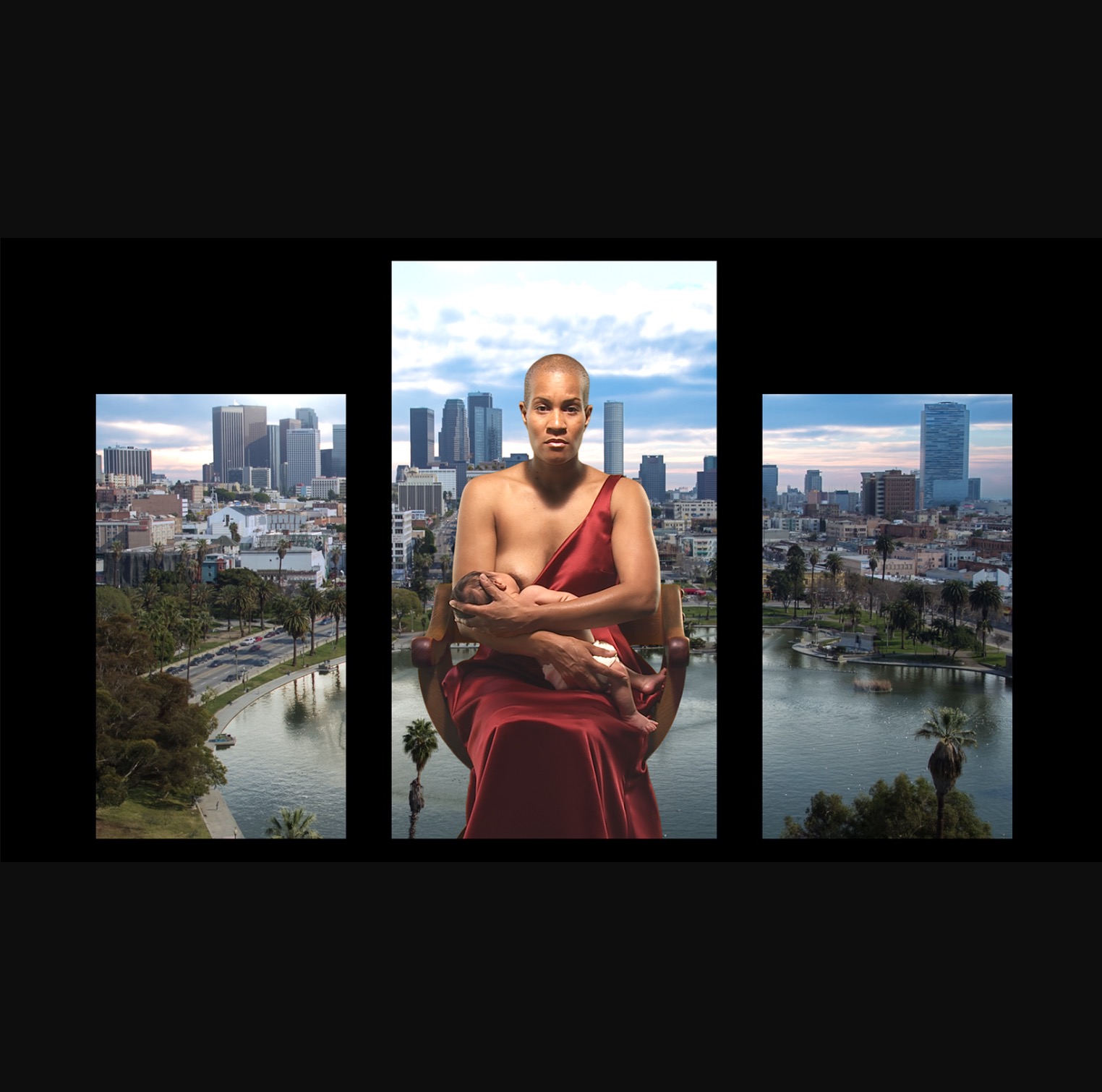

We wander further and pass Henry Moore's sculpture "Mother and Child: Hood" in the apse. A little further and we find ourselves in the North Quire aisle to the left of the High Altar. There, where our cultural references would lead us to expect a Baroque altarpiece with painted, gold-leafed wooden figures, we find instead a nun of quite masculine appearance, cassock, dog collar and boyish haircut. She is pointing at three plasma screens with a remote control. And then begins a fascinating experience for Christians like us, in the year 2016, in an Anglican cathedral rebuilt after the Great Fire of London in 1666. This modern-day triptych lights up to show a shaven-headed, dark-skinned woman of indeterminate race. She wears a saffron-coloured tunic whose colours call to mind the Buddhist monks of Cambodia. Her right breast is bared as she breastfeeds the baby boy in her lap. Behind her, the speeded-up lights of the Los Angeles horizon change from morning pinks, to evening , to nightfall over an extended length of time while she, all slow motion, doesn't take her gaze off ours. The scene is emotionally powerful, wrapped in the mystery between modernity and intemporality, between the most advanced technology and the purity of the miracle of sustaining life by means of warmth and a mother's milk.

FRAGMENT OF LIFE

The screen then fragments, much like a pradella of reliefs on a Baroque altar, into a series of other scenes depicting Mary's life. There is the visit to her cousin Elizabeth, arriving alone through meadows and embracing another pregnant woman, dead fish on a riverbank, a weeping deer filmed in black and white, blackberry bushes teeming with thorns. Seven minutes shot from the Zion National Park in Utah to the desert surrounding the Salton Sea in California and places in between.

The final scene is, however, one of classic beauty. A Michaelangelo-like Pietà with Mary this time light-skinned, in a blue veil, rosy complexioned and holding the marble-like body of her son, just crucified, in her lap. She doesn't cry. She just looks back at us, sorrow-stricken and unable to understand the physical reality before her eyes. She then looks down at her son's body, raises his lifeless hand and kisses it. The scene ends with the screen turning black.

We attempt to think of this level of restraint in any other examples in painting or cinema. We also trawl our literary references til we come up with those comments of Colm Tóibín's on writing his "The Testament of Mary": “I lived in the epicentre of Mary's pain. I would never like to return there." But the gaze of Viola's Mary is unlike anything else. We are too used to the fixed image of paintings and photographs or the moving image of film. In these recordings, as in all of Viola's works that lack narrative discourse, the slow camera maximises our chances of really seeing and feeling the sentiment expressed.

Mary. Bill Viola. St Paul's Cathedral, London

MARY: HOW THE WORK COME ABOUT

Bill Viola's works can be found in some of the world's greatest museums but this is the first time in 2,000 years that a sacred moving image, on video, has ever substituted painting or sculpture in a grand temple of Christianity.

Bill Viola (New York, 1951) took 13 years to conclude these two works for St Paul's. It was in May 2014 that the first video, Martyrs, arrived in the South Quire aisle, to the right of the High Altar, Mary being installed to the left on the 8th of September 2016. Both videos are on permanent loan from the Tate Modern and his wife, Kira Perov, collaborated on both.

Viola admits to long-term 'artist's block' about the figure of Mary and confesses: "She nearly killed us." The theme of both installations was suggested by the cathedral itself: "Until the middle of the 20th century, there were other paintings in the Quires based on Mary and the martyrs. They intimated to me that it wasn't necessary to repeat those themes but, effectively, they were setting me a challenge given that the fundamental thing about them is - for what reason and for whom would you be willing to lay down your life. And that is a devastating question."

Bill Viola believes that there is a universal chain that links human beings: his parents continue to live inside him and he will continue to live inside his son after his death. From a very young age, he has felt drawn to Buddhism and its vision of the world, the idea of eternal rebirth - a principle rather more complex than the life - death - resurrection cycle of Christianity.

In all of Viola's work, silence reigns. It is as if each of the four elements that saturate his characters come straight from the noise in the depths of the universe. The silence in his videos is the equivalent of those areas left deliberately blank by painters, the ones we have to fill in ourselves with our own imaginations or emotions. It is precisely there, in that emptiness, that one finds the greatest of painters, musicians and poets. What Viola aims to do with his videos is to sculpt time: extend it, stretch it, slow it down, wind it in on itself in order to show us all its lines, shapes and ellipses. Somewhat similar to the practice of meditation, fixing the present moment, concentrating one's gaze so as to delve deeper into one's perception of a subject. And channelling the internal question: "What do I see?"

The artist transforms his camera into a second eye to teach us how to look at things the way he believes we should, namely, through introspection and seeing beyond external appearances. He invites us to share in the journey he himself has been on for forty years, one pertaining to three fundamental, metaphysical questions: Who am I? Where am I? Where am I going? Not to look for answers per se but simply to confront the question. He sums it up as: "The men of antiquity called them the mysteries. There are no answers to life or death. I think mystery is the most important aspect of my work. That moment when we open a door and close it without knowing where we're going. To be lost is among the most important things."

Viola is a 'painter' who invented a new palette of technological, numerical colours and created moving pictures that adhere to a new understanding of art. It is a crossover with the great masters of old - Giotto, Bosch, Pontormo or Goya from whom he takes not just themes but also an aesthetic. Nevertheless, far from being a link that prolongs the chain of art, he explains: "I'm not interested in appropriating these images. Rather, it's a case of penetrating into their interior, bringing them to life, inhabiting them, feeling them breathe. What interests me is their spiritual dimension, not their visual form."

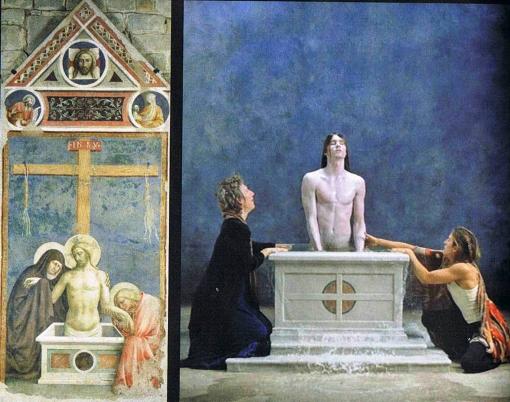

Left: Pietà, Tomaso Masolino da Pinicale (1383-1447). Right: Emergence, Bill Viola (2002)

THE APPEARANCE OF ZEN

When Viola was studying at the The Getty Institute in 1998, the painting that he couldn't stop looking at was Dieric Bouts' (1445) Annunciation: "I fell in love with its austerity and zen-like appearance. The Annunciation is one of those unique moments when, through the figures of the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin Mary, some news is transmitted before words, before language is spoken. The intimate knowledge by which a woman knows she is with child has nothing to do with verbalization. The conversation that is about to be held in this painting is of another dimension. That is its magic - the silence, the stillness ... all of it comes from a very profound place" he says.

But Viola also focuses on the aesthetic language of the classics and transcends it: "In this picture, I would point out the ambiguity of Mary's hands - raised, her palms open and facing each other. One doesn't know if this is in order to receive or to then close as a sign of prayer. The Archangel, however, has his index finger raised. This language of the hands is charged with symbolic meaning. Many of Christ's gestures, for instance joining his thumb and index finger together as a blessing, are also made by Buddhas. In the Hindu tradition, every hand gesture has a very specific meaning."

Annunciation (1445) Dieric Bouts