- Details

- Written by Marta Sánchez

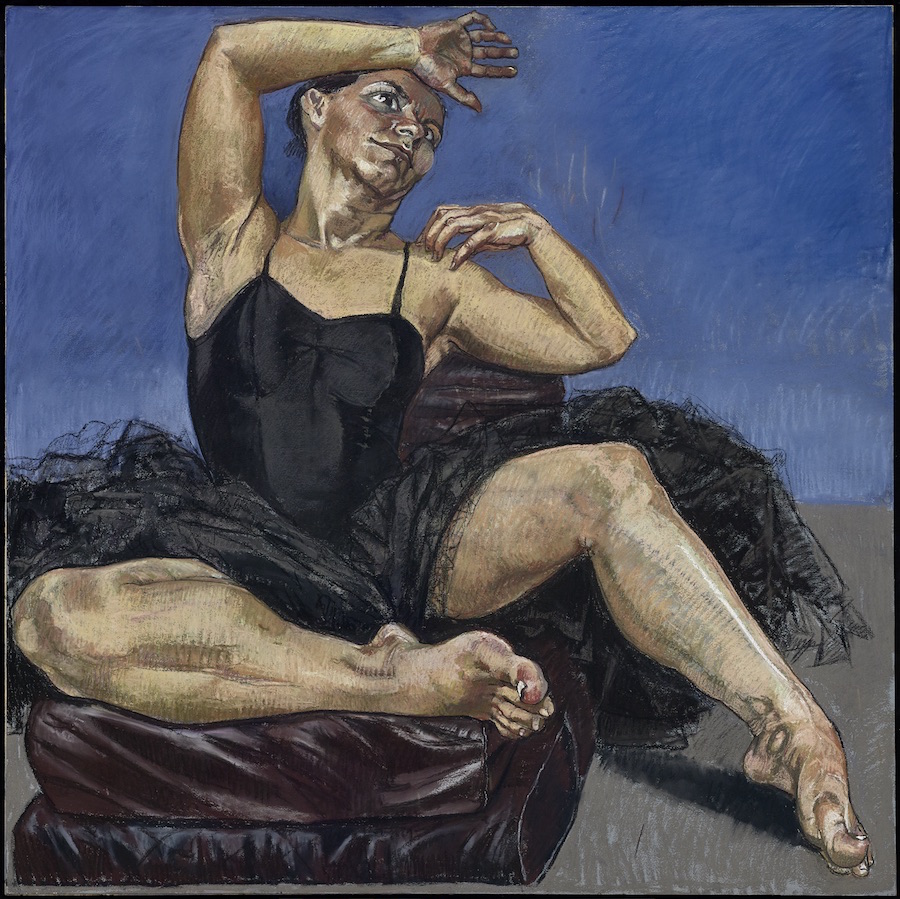

“Art is the guarantee of sanity. Pain is the ransom of formalism. That's the most important thing I have to say." These words couldn't be a truer reflection of what the artist Louise Bourgeois experienced during her lifetime. Considered one of the most influential, powerful and profound creators of the 20th and 21st centuries, Bourgeois (1911 - 2010) persevered in the exercise of her very particular artistic imagination until the day of her death at the age of 98.

Louise Bourgeois: Art From The Heart

Louise Bourgeois as the "mother of spiders". Photo © Peter Bellamy @ www.crystalbridges.com

“Art is the guarantee of sanity. Pain is the ransom of formalism. That's the most important thing I have to say." These words couldn't be a truer reflection of what the artist Louise Bourgeois experienced during her lifetime. Considered one of the most influential, powerful and profound creators of the 20th and 21st centuries, Bourgeois (1911 - 2010) persevered in the exercise of her very particular artistic imagination until the day of her death at the age of 98. Heavily influenced by her lived experience, her childhood and her family environment, her work displays a creative core of the highest order covering hundreds of stylistic bases, formats, materials and narratives. Her works are neither mere plastic nor empty spectacle. They are personal accounts that extend out and relate to the whole collective of human beings, wearing her heart and innermost feelings on her sleeve, shamelessly, in order to reach that same profundity in her spectators. Her unmistakable spider sculptures, her unsettling "Cells", her poetic yet disturbing engravings constitute a vast, unique and fascinating trajectory that transcends the edges of reason and cultural boundaries to plumb the intimate depths of whoever contemplates or engages with her work.

Arch of Hysteria (1993). Museum of Modern Art, New York @ www.moma.org

A childhood woven around her family

Louise Joséphine Bourgeois was born in Paris in 1911 into a family with close ties to the textile industry. Her parents owned a gallery and a restoration workshop with looms where they would weave their own, repair and sell tapestries. This circumstance was to leave a lasting mark on the work of Bourgeois who, throughout the rest of her life, would include fabric, cord, wool and net in a large part of her creations. While her family situation was a comfortable, nurturing and protective one, it was also somewhat unstable with her mother Joséphine contracting a severe case of Spanish flu in 1921 when Louise was just ten. A year later, the family hires an English governess by the name of Sadie Gordon Richmond who becomes a lover to Louise's adulterer father and spends inordinate lengths of time living in the family home as such. This complicated living environment would have a profound effect on Louise's character and she was to experience deep feelings of abandonment and an intense dread of the loss of her loved ones for the remainder of her life.

Saint Germain (1938). Lithograph on paper @ www.moma.org

At 12, Bourgeois' father asks her to collaborate in the family business by contributing her own drawings and patterns. Our budding artist combines this with both her education and the large amounts of time she spends caring for her invalid mother who would suffer repeated relapses and die in 1932 when Louise was 21. That same year, Bourgeois graduated with a first class BA (Honours) in Philosophy although her mother's death plunged her into a deep depression from which she would eventually decide to extricate herself by means of her art. She abandons her studies and seeks out the many workshops that Montparnasse and Montmartre were abuzz with at that time. In 1938, she studies with Fernand Léger, cuts all ties with the family business and opens her own art gallery. This is also the year she marries the art historian Robert Goldwater and moves with him to New York.

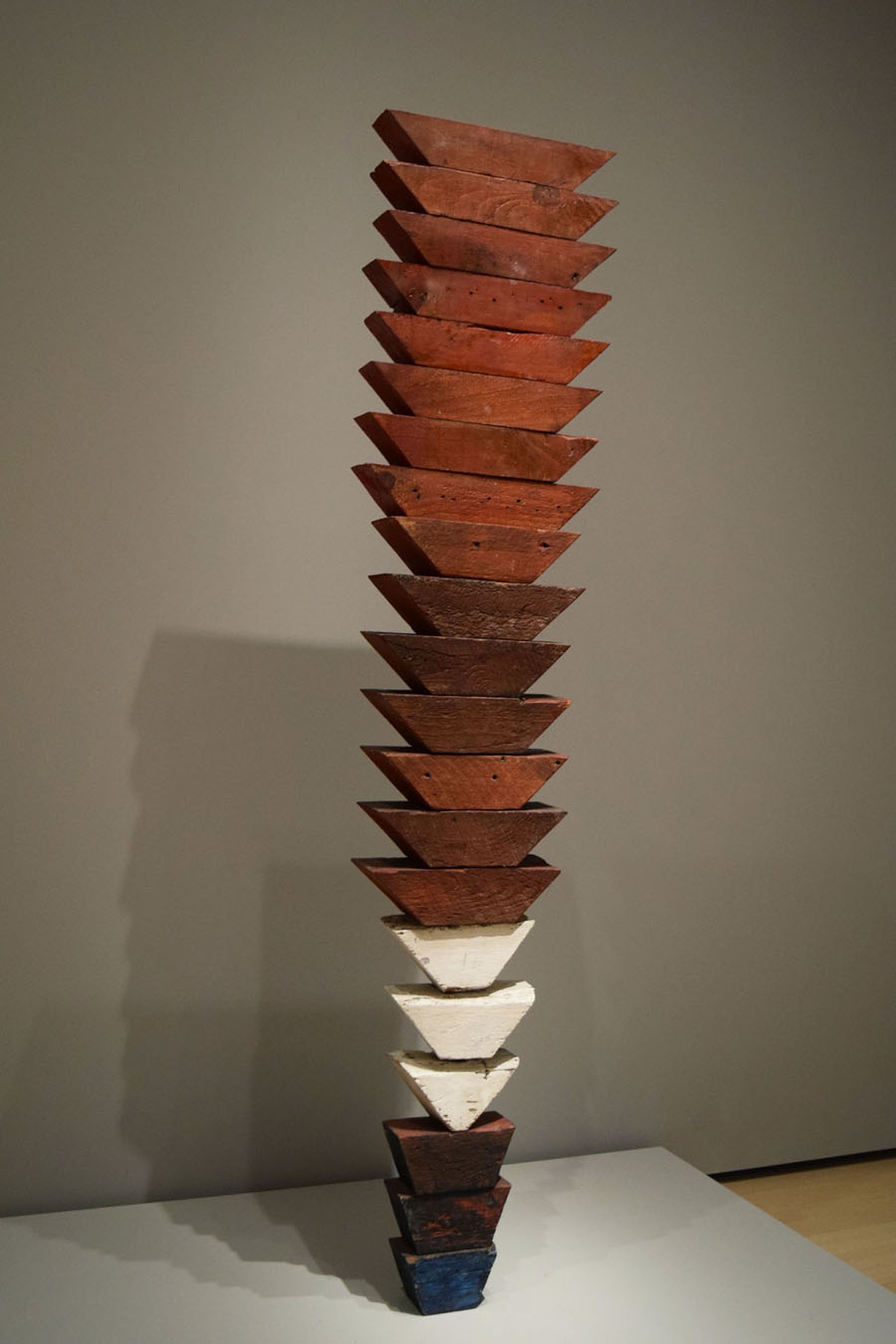

Untitled (The Wedges) (1950). Photo @ www.hyperallergic.com

The artist in New York. The dawn of sculpture.

Now in New York, Bourgeois wastes no time enrolling at the Art Students League and becomes interested in engraving, a technique that would remain in her repertoire til the end of her life. During this time, she researches tri-dimensionality in art and by the mid 1940's has created her first series of wood sculptures, totem poles of highly stylised yet disturbing shapes. 1945 sees the inauguration of her first ever solo exhibition, hosted by the prestigious Bertha Schaeffer Gallery in New York. These are the years when Abstract Impessionism reigned supreme and Bourgeois exhibits alongside its prime movers such as Rothko, de Kooning and Pollock. Nevertheless, her work keeps its distance from the accepted strictures of abstractionism and rather portrays a universe that is far more carnal, explicit and perplexing. Bourgeois' imagination was to remain always on the periphery of schools and tendencies, transcending them with a body of work that was intimate and beguiling.

Following her father's sudden death in 1951, Bourgeois again suffers a deep depression during which she begins to develop her all-encompassing installations that spoke intimately of her memories, lived experiences and traumas. This is also when she starts to attend sessions with a psychoanalyst, coinciding with a period of self-imposed seclusion. In 1964, she comes out of isolation and organises her first solo exhibition for 11 years in which she showcases her latest work both plastic and organic and, for the first time, includes the concept of "lairs", the precursor to her subsequent and spell-binding "Cells".

Destruction and confrontation: facing up to life

The destruction of the father (1974). Photo @ www.historia-arte.com

Bourgeois's artistic trajectory would appear to broaden and flourish from 1973 onwards. These early years see the first of her installations which revolve around the concept of “lairs” and which she uses as a tool to face up to her personal demons. After her husband's death, she decides to take advantage of the pain and resentment she had been harbouring to create works that bare her all, literally. This is the case with "The destruction of the father" (1974), an impactful installation that seems to show the insides of a vital organ whilst at the same time mimicking a sinister dinner party. The setting, with deliberately arranged organic shapes bathed in red light, is the essence of depredation and even "digestion". It is a direct confrontation with her memory of the relationship she had with a father who forced his family to live with his lover Sadie, the tutor much loved by Bourgeois, and even tried to marry Louise off to one of his friends, something which led to her first suicide attempt.

In her book "Destruction of the father/Reconstruction of the father: writings and interviews (1923-1997)", Bourgeois describes the painful process involved in the installation's creation: "With Destruction of the father, the memories it evoked were so powerful and the job of projecting them outwards so hard that [...] I felt as if it had actually happened. It transformed me, really."

On Confrontation (1978), the performance piece A Banquet: A Fashion Show of Body Parts (1978) and various aspects of the work of Louise Bourgeois

Lairs, cells and spiders. A return from the subconscious

The years of psychoanalysis undertaken by Bourgeois can be seen reflected in much of her output but it is only after 1986 that she starts to create specific pieces, namely "The Cells", to expose the essence of her relationship with social contracts, her lived experiences and the subconscious. These were enclosed installations, each telling its own story and communicating that experience to the minds of whoever enters in. The original one, "Articulated Lair" (1986), was to be the first in a series of some 60 works created using theatrical elements, staging, interactive spaces and, as ever, the presence of emotions. Bourgeois created these scene-settings to connect her work with certain traumatic life events, using them for liberation from them. When the spectator enters inside and experiences the artist's subconscious world, they too come to share her nightmares.

CELL XXVI (2003). Photo @ www.champ-magazine.com

In the mid 1990s, Bourgeois begins to explore another of her obsessions, namely the spider as mother, predator and weaver. Reverting back to her childhood references (spiders and the sick but protective mother), and by now in her eighties, Bourgeois begins to sculpt designs in the form of spiders that are equally terrible and fragile, both victim and destructive force. For her, the spider represented "intelligence, productivity and protection." She creates monumental sculptures (for instance, the famous "Maman" of 1999, on display outside the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao) and diminutive ones ~ beings who appear almost mythological and whose mission is to reconstruct and restore. “I come from a family of restorers.”, she once said. “The spider is a repairer. If you bash into the web of a spider, she doesn't get mad. She weaves and repairs it."

Maman (1999). Photo @ www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus

Louise Bourgeois died in 2010 at the age of 98, never having stopped working or researching until the very last days of her life. Her oeuvre, vast and nuanced, is fundamental to our understanding of artistic evolution in the 20th and 21st centuries.

EXHIBITIONS

Bourgeois saw the inauguration of her first solo exhibition in 1945. From then on, her work was exhibited in many galleries and museums throughout the USA until she finally achieved universal recognition. For decades, her exhibitions have travelled the whole world and attracted thousands of visitors. Still today, they continue to arouse enormous interest, as much amongst specialist critics and art historians as the public.

"Louise Bourgeois" at the Tate Modern, London (2007-2008)

In 2007, London's Tate Modern organised a comprehensive Bourgeois retrospective in collaboration with the Georges Pompidou Centre, Paris. The exhibition then moved on to various museums in the USA.

"HONNI soit QUI mal y pense" at La Casa Encendida, Madrid (2013)

HONNI soit QUI mal y pense (Shame on him who thinks ill of it, referring to her indifference to people's perception and judgement of her work) is the title of a drawing by Bourgeois used to name an exhibition organised by Madrid's La Casa Encendida in 2013. The show focused primarily on the artist's output during the last ten years of her life.

Exhibition curator Danielle Tilkin (in Spanish) describes Bourgeois' work as autobiographical, intensely retrospective, wholly independent of all other schools and movements, engaged in social discourse at any given time, full of black humour, critical distance, internal conflict and reflection on the past and present, reproduction, time and the constant cycles of life.

Bourgeois' assistant Jerry Gorovoy (in English) gives his intimate, in-depth analysis.

Louise Bourgeois (in French) ~ "You have to look at yourself truthfully. Only when you look and like yourself and accept yourself does the silence dissipate and you can then enter into a dialogue. Things don't have to be black or white. Things are much more interesting if they're grey. And if they're subtle. Me, I want to invent something new. I want to invent a sculpture, a script, signs. History is of no interest to me. I'm sick to death of history and tradition."

"Louise Bourgeois. Structures of Existence: The Cells" at the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao (2016)

In collaboration with the BBVA Foundation, Bilbao's Guggenheim Museum organised a large exhibition of the artist's famous "Cells" (28 installations in total) and of the build-up that lead to her developing these pieces that were so full of her own personal imaginings.

BOOKS

He disappeared in complete silence (1947)

This essential publication compiles the imaginings of a young Louise Bourgeois, both in the plastic and artistic as well as the literary sense. It was created just before her transition to sculpture, a discipline she arrived at via her idiosyncratic wooden "totem poles" and the book's illustrations reflect the research she did prior to this transition. The text, brief and intense, derived from the artist's efforts to disseminate her work and make it better-known on an international level. Although not a success at the time, the book has since come to be considered a reference point fundamental to understanding her work, even though the book wasn't eventually completed until several decades later.

Louis Bourgeois: Destruction of the Father / Reconstruction of the Father (Writings and Interviews, 1923-1997)

“Every day, you have to abandon your past or accept it, and then, if you cannot accept it, you become a sculptor.” This is just one of the many reflections appearing in this fascinating book, which brings together the thoughts and texts Bourgeois collated over seven decades. The volume also includes several interviews she gave that detail her concept of art and and give clues as to the origins of much of her work. One will also find in its pages some of her "pen-thoughts", illustrations that combine text with drawings. It is, without a doubt, essential reading in order to understand Bourgeois's vast and rich body of work.

Structures of existence: The Cells. Louise Bourgeois (2016)

The catalogue for the Guggenheim Bilbao's magnificent exhibition of "The Cells" is an exhaustive study of this suite of sculptures, fundamental pieces in the artist's work. The study includes the complete catalogisation of every installation, as well as keys to the creative process by which Bourgeois came to design and realize each of them. We can also find in its pages a thorough analysis of the concepts that form the basis of her work, namely space and memory, conscious and subconscious thinking, the body and architecture.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Louise Bourgeois: biografía, obras y exposiciones - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

2019: The Year of Rembrandt. Amsterdam kicks off Holland's 350th anniversary celebrations for the Old Master with its exhibition "All The Rembrandts of the Rijksmuseum" which will then make its way to Madrid's Prado as "Vélazquez, Rembrandt, Vermeer ~ Artistic Likenesses from the Spanish and Dutch schools". One would be forgiven for thinking the central gallery of the Rijksmuseum was less than sixty metres long because, on opening its panelled doors of leaded glass, our eyes are immediately drawn to the illuminated hand held out towards us by Captain Frans Banninck Cocq. It beckons us from that distance away, making us want to step into the canvas with him as he gives the order for his company to begin their night watch through the streets of Amsterdam.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

2019: The Year of Rembrandt

Amsterdam kicks off Holland's 350th anniversary celebrations for the Old Master with its exhibition "All The Rembrandts of the Rijksmuseum" which will then make its way to Madrid's Prado as "Vélazquez, Rembrandt, Vermeer ~ Artistic Likenesses from the Spanish and Dutch schools".

One would be forgiven for thinking the central gallery of the Rijksmuseum was less than sixty metres long because, on opening its panelled doors of leaded glass, our eyes are immediately drawn to the illuminated hand held out towards us by Captain Frans Banninck Cocq. It beckons us from that distance away, making us want to step into the canvas with him as he gives the order for his company to begin their night watch through the streets of Amsterdam.

The central gallery of this neo-Gothic museum somewhat resembles the stem of a basil plant, with its lateral chapels branching off either side of the central aisle and housing the world's largest collection of Dutch Golden Age paintings. The visitor is thus forced to zig-zag between them while, at the very end, in the apse, as if an alterpiece, hangs Rembrandt's "The Night Watch", his controversial, secular, colossal painting of 1642.

From the very start of this visit, we are already getting a sense of something quite different from the mythological, religious and military scenes usually found in other collections of 17th century Dutch, Spanish and Italian paintings. Where are the heavens opening to reveal the glory of God, the Depositions of Christ, the Flights from Egypt or the Epiphanies? Where are Apollo and Daphne, Danae, Proserpine?

Even before arriving at the Rembrandt gallery, several other pictures, oddly small in format, showcase another style of painting. Theirs saw the establishment of a brand-new genre of painting, one that is striking not just for its relentless verism but also for its never-before-seen themes. Domestic scenes portraying an urban, bourgeois life and families inside their homes of oak furnishings, Delft tiles and kitchens bathed in light. And their world of scenarios that are essentially feminine and intimate in nature ~ women standing alone, reading a letter or playing the harpsichord, cradling a baby, sweeping a room or putting on a pearl necklace, their faces lit by daylight from an open window. Scenes that almost seem to be happening on a lazy day off.

Vermeer, Woman Reading A Letter (1663-64), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Staggering numbers

There has been, perhaps, no other country ever where so many paintings have been produced in such a short period of time. It is estimated that between 1600 and 1700, up to 10 million paintings were produced in the Netherlands. Between 1650 and 1675, both Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) and Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) were active as well as at least half a dozen other top-notch painters such as Carel Fabritius, Gerard Dou, Gerard ter Borch, Frans Van Mieris, Jan Steen, Pieter de Hooch and Gabriël Metsu.

What made such prolific artistic production possible? What led the United Provinces to write a fundamental chapter in the history of art? An art which, incidentally, was at once so very localised yet so eternal?

From a technical point of view, the theorist Karel van Mander, echoing Giorgio Vasari, confirms that Golden Age Dutch painting derived from 15th century Flemish painting, from the preciosity of Jan van Eyck's, Robert Campin's and Roger van der Weyden's paintings, still under the guise of religious scenes but also depicting the interior of contemporary homes, their fireplaces, chancellors' bibles, saints' clogs, the damask and fur of their garments and the lilies of archangels.

The artists' lives were, coincidentally, punctuated by highly dramatic, military and political events that did not, however, seem to have left any mark on their work. The 17th century was one of the bloodiest in history, its wars notorious for their long duration. The Netherlands, divided by Civil War into Calvinists and Catholics, fought the Spanish Crown in the same way it fought the sea which inundated its plains time and time again, filling its landscapes with windmills, dykes, canals and bridges. They were Master Naval engineers whose fleets managed to achieve dominance over most of the world's commerce. Until the 1640's, the Dutch empire extended from Brazil to Africa and from Indonesia or Japan to the east coast of North America, establishing its capital there as New Amsterdam, now known as Manhattan.

In 1602, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was founded, its 160 ships sailing the oceans transporting and unloading extraordinary cargo ~ tonnes of blue and white Chinese porcelain, wood and grain from the Baltics, Persian rugs, sugar from Brazil, fruit from the West Indies, spices and pepper from Java, Sumatra and Borneo. Turkish sultans sent tulips and with them came 'tulipmania' which, in the 1620's, almost caused riots due to a price rise. A few absurd sales receipts still exist ~ luxury mansions paid out in exchange for a single bulb. It was the first speculation bubble in history.

Amsterdam and its port thus became the greatest trade centre in the north of Europe. A Stock Exchange was established there and is considered, after that of Antwerp in 1460, the oldest in the world. Founded in 1602 by the VOC, and the first to function like the modern stock market, its aim was to create funding for future commercial shipping.

This global trade network created an elite clientele with abundant amounts of money with which to adorn their houses. The decorative arts flourished, as did the quest for luxury items and, above all, paintings which were to become the new status symbols. Gone the patronage of aristocracy and Church, it would be the bourgeoisie from now on paying the piper and calling the tune on the subject matter to be painted. And they wanted to see a reflection of their own lives, their hardships and dreams in those paintings. They wanted to feel recognised. Dutch art, artists, buyers and dealers were the catalyst for the future international art market, such as we know it today.

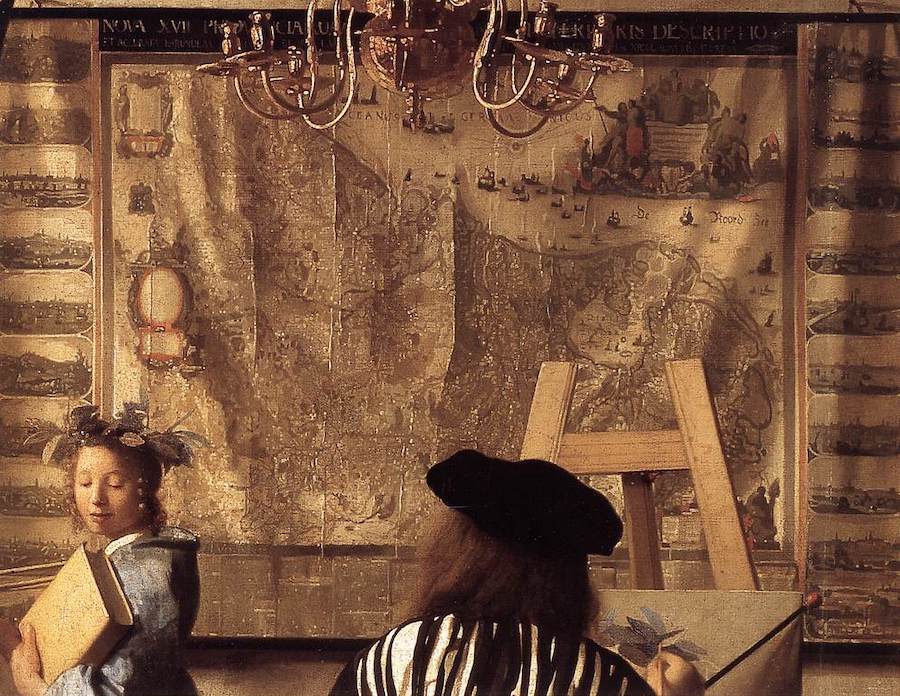

Vermeer, The Art Of Painting (1666), detail showing a map of the United Provinces, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Leapfrogs and bounds

This is script being written and informing our progress through the galleries, providing context and background against which Vermeer in Delft and Rembrandt in Amsterdam showcase their own particular way of painting. In the case of Vermeer, it would appear to be a natural progression from the mentality of his time. For Rembrandt, it was a giant leap forward.

On a wall near "The Night Watch" hang three tiny paintings that signal, from the outset, an ethereal calm in space and time. These are all three Vermeer paintings owned by the Rijksmuseum. "The Little Street" (1658) measures little more than fifty centimetres and is so lifelike it appears not to exist at all. It is as if there were a hole in the museum wall through which a real street scene in Delft can be glimpsed. Perhaps for this reason, it is said of Vermeer's art that it predates the realism of photography, the only artform to, centuries later, attempt to portray the very air surrounding figures in this way.

Vermeer, The Little Street (1658), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

"The Milkmaid" (1659) is dressed in Vermeer's favourite colours of yellow and ultramarine, intently pouring a fine stream of milk into a clay bowl. She looks as if she is not to be disturbed. The still life on the table with its crusty bread and specks of sunlight, the wicker basket and, most noticeably, the wall behind her bathed in light creating a shadow under the nail, the different colourations of whites marking a stain or, as in the corner, the ochre variations of damp combine to form an intense reality, small but perfectly-formed, vast and magical. The precision of tone is remarkable. An artist must, in short, have the gift of seeing everyday things in a different way to us. Creativity has to entail something like how to illuminate these ordinary things with a brighter light, with more concentrated attention, with a distinctly powerful charge. When Rembrandt paints a glass of wine, it ceases to retain its natural state of being a glass of wine and becomes, rather, part of an action. He beams theatrical light onto it, he sets it on a stage. Vermeer, on the other hand, isolates it, wanting a light just for this one glass, he grants it the virtue of being itself, unique, material and independent, in a moment of time that is motionless. Vermeer paints the time that flies between things.

Vermeer, The Milkmaid (1659), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In the years when Rembrandt and Vermeer were active, the world was engaged in a scientific revolution. New ideas were being touted about what it meant to 'see'. People had started to believe Nature was hiding a world invisible to the naked eye and that science should focus on researching it and finding out. There was a wave of empirical thought needing to back itself up with instruments able to measure Nature and allow us to see parts of the world that had been hitherto invisible. Hence, the 17th century saw the invention of the thermometer, the barometer, the telescope and the microscope. And its painters, determined to discover Nature and to paint it using an array of optical effects, went back to relying heavily on lenses and camara obscura devices. We do not know whether Vermeer used such techniques in his painting or not but what is certain is that he was familiar with the effects they produced and how light influenced how we see the world. He reproduced how it accentuates colour tonalities until they appear jewel-like, how it blurs or sharpens the outlines of figures, how it highlights where the touches of light brighten and polish whichever reflective surface the sun falls on.

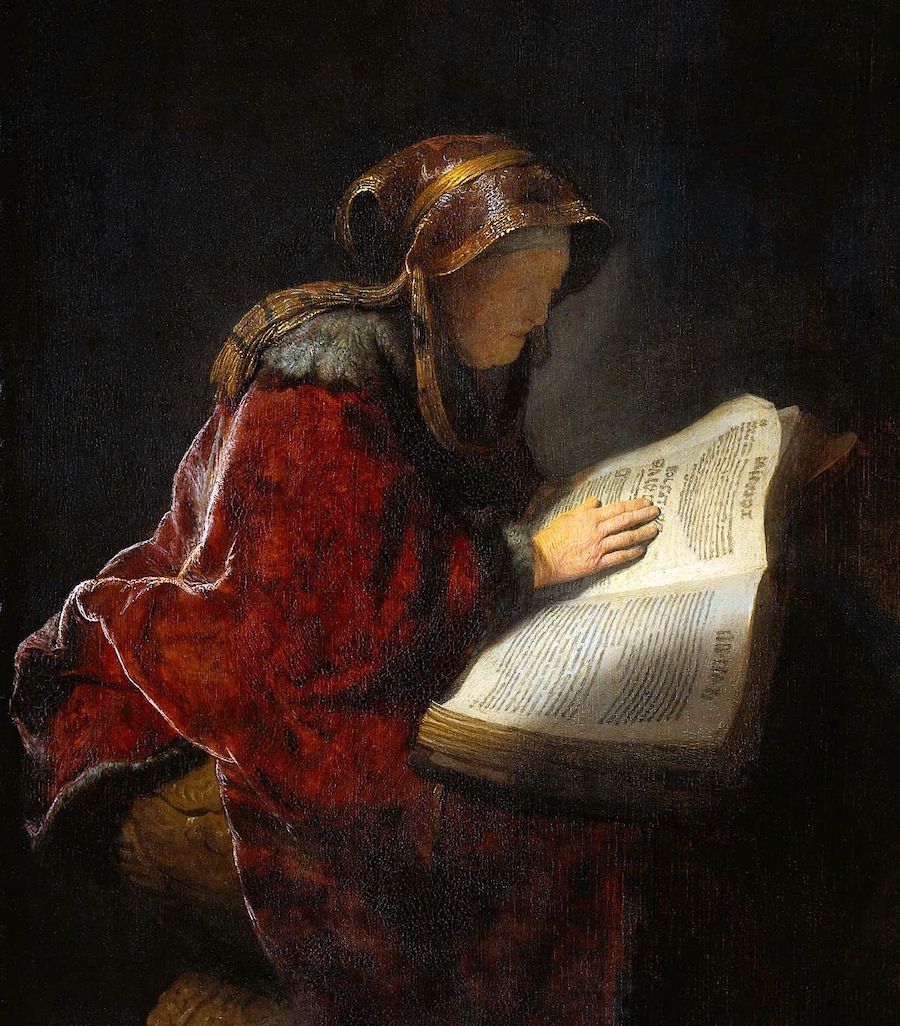

Vermeer painted "The Milkmaid" some 16 years after Rembrandt started work on "The Night Watch". Both paintings were a pictorial revolution but they were poles apart. To simplify Svetlana Alpers' study of 17th century Dutch painting, one might say that Vermeer represents the pinnacle of descriptive painting and its debt to observation whilst Rembrandt uses narration and historical themes as a pretext for injecting a certain wildness into his painting as the key to expression, action, gesture and the innermost recesses of the soul. His studies of light and matter are merely a means by which to paint the depths of pain, loneliness, failure, power, blindness or life just before death.

Rembrandt, The Prophetess Anna (Rembrandt's Mother) (1631), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Ten years, ten days

In a documentary about the last years of Rembrandt's life, Simon Schama describes a scene. It is 1885 and a young artist visiting the Rijksmuseum stops dead before a painting, his eyes transfixed, breaking into a feverish sweat as he gazes at the adored work. "I would give ten years of my life if I could simply sit and meditate, with a dry crust of bread, for ten days looking at it." So what was it about "The Jewish Bride" that so mesmerised the young Van Gogh? Days later, he would write that Rembrandt had painted it with "a hand of fire". Schama interprets the impact on Van Gogh as that of any masterpiece ~ it takes aim directly and viscerally. Van Gogh was another painter who took brushstrokes to their most physical extreme and this final work of Rembrandt's left him spellbound. In it, the Old Master, by now penniless and at death's door, depicts the physical incarnation of love. Its whole meaning is that of touch and caress. "The Jewish Bride" is a symphony of four hands, those of a couple. A man's hand on his wife's heart, the woman's hand touching this hand, a man's hand protectively around his wife's shoulder ...

Rembrandt rushes this final painting with the rage of his materials. The sleeve he paints here is not easily explained and one would need to be standing, as Van Gogh did, right in front of it. The sleeve is a physical crust in dozens of shades of gold, a mass of pictorial density that has a whole world of matter embedded in it: pieces of egg shell, crushed glass, mud, silica, ... The Old Master is acting on the painting the way the likes of Pollock, Freud and Kiefer would act on theirs centuries later ~ painting emotions with their materials.

Rembrandt, The Jewish Bride (1662), Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

"The Jewish Bride" features in the exhibition, as does "The Night Watch" with its outstretched hand, along with the whole astounding collection - the world's largest - of Rembrandt's canvases, drawings and etchings owned by the museum. Nevertheless, what makes this exhibit unique is something else. It is, essentially, about finding oneself in the presence, just a few feet apart, of two genius but contrasting artists. In and out of Rembrandt, on to Vermeer, retrace our steps back to Rembrandt and ..... start all over again. As Simon Schama said about them: Vermeer versus Rembrandt ~ crystallization versus emotion.

Rembrandt, The Night Watch (1642), Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

All the Rembrandts at the Rijksmuseum

Rijksmuseum

1070 DN Amsterdam

Curator: Jonathan Bikker

15 February ~ 10 June 2019

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

Leïla Slimani, born in 1981, is a French-Morrocan author and the 2016 winner of France's most prestigious award for literature, The Goncourt Prize, for her second novel, "Lullaby". In a distinctly French style, with a tone reminiscent of her compatriot Emmanuel Carrère, Slimani narrates, with both lightning rhythm and a sluggishness typical of day-to-day routine, a dizzying plot that leaves the reader in the uncomfortable position of being able to identify with these easily-relatable incidents. The reading of the novel is accelerated by the flow of her narrative in its search for what is hidden behind what we know to be fact from page one.

|

Contributing Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

Leïla Slimani. Photo @ Heike Huslage-Koch

Leïla Slimani, born in 1981, is a French-Morrocan author and the 2016 winner of France's most prestigious award for literature, The Goncourt Prize, for her second novel, "Lullaby". In a distinctly French style, with a tone reminiscent of her compatriot Emmanuel Carrère, Slimani narrates, with both lightning rhythm and a sluggishness typical of day-to-day routine, a dizzying plot that leaves the reader in the uncomfortable position of being able to identify with these easily-relatable incidents. The reading of the novel is accelerated by the flow of her narrative in its search for what is hidden behind what we know to be fact from page one. Fiction and non-fiction intermingle in such a way that it becomes difficult to distinguish one from the other. The characters dance around the protagonist, a strange and unfathomable woman who lets only parts of her personality show so that the reader only forms an idea of her character gradually as the book progresses. Nothing is left to chance here. The characters are all intertwined up until their phobias and weaknesses are seen or perceived by others. With painstaking precision, she describes the atmosphere in the house, where most of the action develops, as if it were a discomfited witness to the suffocating reality within it.

Although having nothing in common with each other, the novel's "perfect nanny" Louise does bring to mind the figure of Vivian Maier, widely known as The Nanny Photographer - an enigmatic and solitary figure who spent her adolescence in France, returning to her American birthplace in the 50's, first New York and later Chicago, to work in childcare but never forgetting her true vocation - photography - and whose body of work, today internationally renowned, went undiscovered until after her death in 2009. She managed to the find a source of inspiration and gratification in the mundanity of her daily life, which she captured in thousands of photographic images that also served to alleviate whatever frustration she may have felt in an otherwise unrewarding job. The streets, with or without people, the children she took care of and her many ingenious self-portraits were captured in over 100,000 negatives, almost all of them recovered by the collector John Maloof. Some Super-8 films were also found along with audio recordings, all of which made Vivian Maier an exceptional chronicler of two American metropolises.

This digression helps us understand how little we know about the human condition and what remains hidden behind seemingly normal gestures and acts. Slimani shows us the enigma that underlies our subconscious and how, when one least expects it, it leaps ferociously into the wrong scenarios, thereby provoking incompehensible actions and reactions. The narrative manages to confuse the reader who is trying to make sense of what is irrational, what simple appearances don't reveal, what escapes our observation, the small details that describe to perfection the atmosphere breathed inside and outside the place of events. And it's a book that is hard to recommend to those mothers obliged to leave their children in a stranger's hands for many hours without really knowing what is going on in their home.

The novel pulls no punches when dealing with issues such as the female condition and the debate around motherhood versus career. The dilemma that exists between child-rearing and/or a professional life highlights the complexity of that choice. Parents justifying themselves and their dereliction of duty or priorities at any given time reflects the difficulty in deciding how to confront the situations we often find ourselves caught up in.

The novel was inspired by real-life events that took place in New York City in 2012.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Leïla Slimani: Lullaby (Chanson Douce) - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

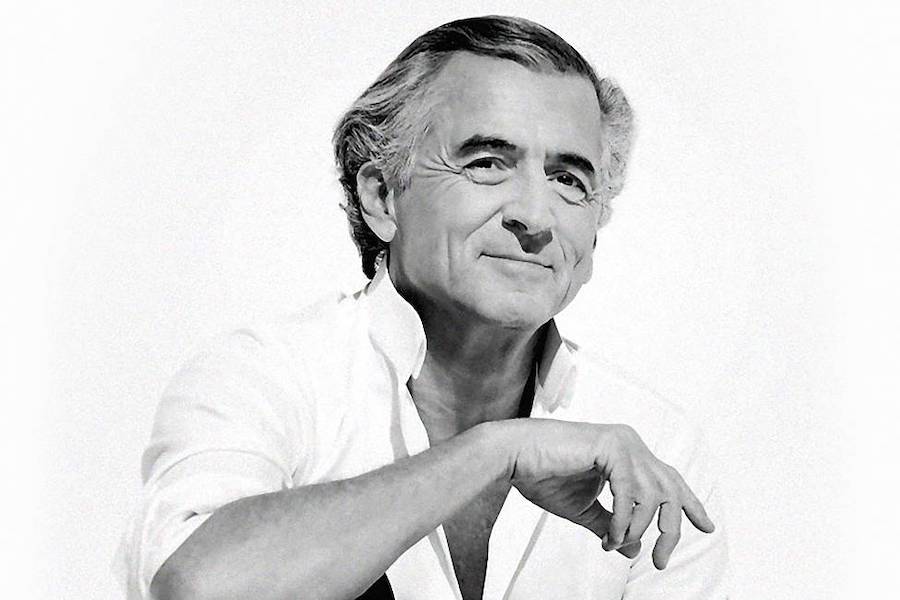

One of the great thinkers and intellectuals of our time, Bernard-Henri Lévy (Algeria, 1948) has successfully launched a theatrical tour around Europe with his work Looking for Europe. It premieres in Spain next Wednesday, at the Teatro Olympia in Valencia, then goes to Barcelona and Madrid. In his monologue he defends democratic and liberal values from the threat of populism. He has also just published his book The Empire and the Five Kings, (Henry Holt & Company Inc) that explores the loss of global leadership in the United States and how the five powers, the ancient Empires: Russia, China, Turkey, Iran, and Sunni radical Islamism are weakening the values that have distinguished our western civilisation.

Author: Elena Cué

Bernard Henri-Levy (Ali Mahdavi)

One of the great thinkers and intellectuals of our time, Bernard-Henri Lévy (Algeria, 1948) has successfully launched a theatrical tour around Europe with his work Looking for Europe. It premieres in Spain next Wednesday, at the Teatro Olympia in Valencia, then goes to Barcelona and Madrid. In his monologue he defends democratic and liberal values from the threat of populism. He has also just published his book The Empire and the Five Kings, (Henry Holt & Company Inc) that explores the loss of global leadership in the United States and how the five powers, the ancient Empires: Russia, China, Turkey, Iran, and Sunni radical Islamism are weakening the values that have distinguished our western civilisation.

With this geopolitical analysis of the current global situation, what do you think will happen to Europe?

The first possibility would be for it to disappear from the world map and convert itself into a battlefield between Americans, who are losing their power, and the five new empires trying to defeat them. We may end up being a middle ground, where some will try to overthrow others. The solution would be for Europe to take advantage of this situation, to wake up and become a new superpower. But what is certain is that, in the new configuration of the world, the American umbrella no longer works. Donald Trump has said it very clearly, but Obama had already said it before.

Indeed, the debilitation began before Trump.

Yes, Trump is the epiphenomenon, not the main phenomenon. The main phenomenon is the fact that Europe and America are disconnected, and that happened before Trump.

In reference to the five powers, who you state want to end Europe, what would be their greatest benefit to come from this downturn?

For the forgotten and unfortunate populations, for example, the women of Saudi Arabia, democratic dissidents of China, or the youth of Iran, Europe is an example, a reference and above all, a symbol of hope. Europe is the light at the end of the tunnel. The main interest of these five powers would be to put out that light, to ensure their communities stop dreaming about Europe and that Europe cease to be a symbol of hope for them. As long as Europe exists and is strong, it poses a danger, not only from a geostrategic point of view, but above all from an ideological and spiritual stance. Because for all its people, Europe represents the image of a different future, as opposed to the harsh reality of what they currently are.

It seems that Russia would benefit most from Europe’s current weakness as it would further their geostrategic objectives.

China and Russia share their roles. China has the strength and Putin the intelligence. The money comes from China or the Arabic world, while reflection and strategy come from Putin.

Last year you created the play Last exit before Brexit performed in London. What do you think will happen in Europe without Great Britain?

What we are currently witnessing is that it is not so easy to leave Europe. The Brexit supporters defended their right to control their future, yet three years later, they have not obtained any positive result but they have lost control of the situation. The United Kingdom is out of control, although they are still in time to wake up from this nightmare.

Are you optimistic?

Rather realistic. Without Europe, the United Kingdom is going to collapse, and without the United Kingdom, Europe will suffer serious damage to its spirit and heart. Democratic liberalism and the merger of the political and economic is an English contribution; it was their great understanding of the best system for society, which the English devised in the XVIII and XIX centuries.

You also objected to the way Cameron used the referendum. Why is that?

Because you cannot respond with a "Yes" or "No" to such complex political issues. I'm not saying that people cannot have an opinion on such matters, on the contrary, it is exactly what democracy is about. However, it was a very broad issue which implied centuries of history, memory and ties between the United Kingdom and the rest of the world. The referendum should be seen as last resort after the other democratic possibilities for political decision-making have already been exhausted. The difficult thing about democracy is that it requires deliberation and commitment. When we are about to answer with a "Yes" or "No", you have to ask, are we in a plebiscitary or a Caesar-like regime? Or are we in a regime where democracy serves as an alibi for tyrants?

In Looking for Europe, you intend to influence the next European elections by drawing attention to the threat posed by populism. How do you think Europe can fight populism?

Populism is a threat to ideas, intelligence and beauty. It is also a threat to the complexity of things and to coexistence. Democrats and Liberals have to wake up and start fighting. They are too timid. I call for an awakening, which is the meaning of this work. It is not just a cry for attention. As liberal Europeans we do not want the simple solutions populism and the independence movement offer, and for that reason we have to wake up and speak up, bringing together the true power of speech and accept our opinions. If you are pro-Europe and pro-capitalism, you say it but in a very quiet voice. For example, the war against the elites is a disgrace and a suicide for Western democratic societies. We need to say all that before it is too late.

All of this is present in your work?

I speak of the "yellow vests" and of the outraged, of this whole movement which in my opinion, under the guise of democracy, is actually undemocratic. They are going to drag along our societies, just like at the fall of the Roman Empire or the end of classical Athens. I do not want that, which is why I have fought in places as far away as Afghanistan, Pakistan, or Kurdistan throughout my whole life. Now, I am convinced that the fire is in my house. And my house is France, Spain, Italy... That is why I have written this play, to return home and confront the war that has been declared by the populists.

Is the neoliberal ideology that caused the 2008 crisis not another equally dangerous threat against democratic and liberal values?

Yes, but it is a threat that can be controlled. Liberal capitalism has many flaws, but it has one virtue: it is constantly in the process of auto correction. It goes from crisis to crisis and it is the only economic regime in history to survive and overcome them. It is not the perfect correction, we know that there are bankers who have not understood the lessons of 2008, but capitalism is a machine that integrates the lessons of the past. It always has been. In this sense, yes, it is a threat, but a controlled one.

In 1976, you promoted the movement of the so-called new French philosophers, one of which was Alain Finkielkraut, who has just become the target of an anti-Semitic attack lead by a part of the yellow vests. The acts against Jews increased by 74% in France last year. Why do you think this is happening?

The real problem is not only that one group has insulted Finkielkraut, but that all those surrounding groups, such as the "yellow vests" in Paris and other cities, have not stood up in protest and said: "Not in our name!" Journalists in France say it is a small group. But why has the big group not condemned this aggression?

It is worrying.

We are experiencing the third great period of anti-Semitism in France and Europe. The first one was at the end of the XIX century, the second one during the 1930s and the third one is today. We know how the first two periods ended: in the worst possible way, in the form of suicide for European societies. What we can expect from this third period is that at least we have learnt the lessons from the past.

"Anti-Zionism is one of the modern forms of anti-Semitism." Do you agree with these words by President Emmanuel Macron?

I do not think that is the point. You can be a Zionist or not, you can love Netanyahu or hate him. The point is that nowadays, if you want to create and see an anti-Semitic movement grow, the only way you could do it is to be an anti-Zionist at the same time. It is a matter of political mechanics.

Why?

Because what an anti-Semite needs is to convince people that there are good reasons to hate Jews. What are they going to say today? That the Jews have a different chromosome? That they have killed Christ? No, of course, that does not work anymore. The only way anti-Semitism could work today is to say that Jews are friends of a State that is very bad and possibly fascist in dealing with another group, the Palestinians. If you manage to develop this notion, then you can create a real anti-Semitic movement in Europe. In terms of mechanics, ideology and politics, that is the only way. I am Jewish, but not Zionist. If I were a Zionist I would live in Israel and believe that this is the fate of the Jews.

What is the solution for Palestine?

Two states, one next to the other.

In your book, you also speak about the betrayal of the Kurds. They are courageously carrying out their duty fighting against the Islamic State. The Kurdish people are very grateful to you for your support with this book and your documentaries. As an opponent of nationalism, why do you defend the Kurds' pursuit to form their own nation in this case?

The difference is that they are being massacred by Erdogan, by the Iranians, and by Bashar al-Ásad. If the Barcelona separatists were faced with a dictator who killed them, I would be in favour of their independence. But they have a democracy, which is the exact opposite. For more than a century the Kurds have been annihilated by the powers that control them. In this case, independence is the only way out of death. Therefore, I am not in favour of their independence for nationalist reasons. I have never been a nationalist. I am interested in human rights and the rights of the body, meaning the right that the body is not martyred, tortured or end up assassinated.

It also shows that the Kurds profess a more moderate Islamism.

That is the second reason. It is something I mention a lot in the theatre performance. In Europe, we are desperately looking for the ideal Islam, one that is compatible with democracy, human rights, secularism, etc. An Islam that has the ability to overcome Islamic Jihadism and the terror we have of it. We had it in Bosnia and we have it in Kurdistan and in both cases we can observe the tragic paradox of Europe. This is one of the main themes of my play: when we have them, we let them fall. This is a spiritual, metaphysical, political and moral error.

The Muslim population in the West is increasing, particularly in France. You wrote the book Public Enemies with Houellebecq. Do you think it would be possible to have an Islamist government in France, as you write in your book Submission?

No, because Europe's liberal civilisation is much stronger than Houellebecq realises. It has the capability to integrate elements from other parts of the world, including Islam, but not to be devoured by Islam, that is not going to happen. I believe that the European civilisation is very strong; the only empire to survive all its crisis’ is the European Empire. "Empire", not to be understood in the sense of imperialism, but looking at Europe as a civilisation which, beginning with the Roman Republic, has continuously survived its looming death in order to revive. It is a unique case as with the other empires, when they die, they die. Europe may seem to die, but it comes back. In my work, I say that Europe, the West, is the only empire where its grave is always a cradle.

In your book The Genius of Judaism, you state that in Judaism the focus is not necessarily on believing in God, but more importantly on the study and understanding of God. Continuous questioning and reinterpreting.

That is what the Jews are asked to do. It is not so much about believing, but is about studying. Understanding, working and introducing more complexity in the world, or at least interpreting the complexity that occurs in the world and avoiding simplification.

You have mentioned that your way of thinking would not be the same without Foucault and teachers like Althusser or Derrida. From this multiplicity, how would you pinpoint your philosophical thought?

My way of thinking has roots, but the product comes from me. At my quite advanced age, I really believe this. I am not anyone's son. I was a good son, first to my parents and then to my teachers. I believe that today I think at my own risk and from a perspective that is mine. Indeed, the roots come from French structuralism, Jewish thought and Albert Camus. Those are the three great pillars.

A big feminist demonstration has taken place recently. In your book Women and Men written with Françoise Giroud it seemed that your thought was closer to the feminine while Giroud's was closer to the masculine. What do you think?

The relationships between men and women, and in particular my relationships with women were, and still are, one of the great subjects of my life. Secondly, and it may not be very politically correct, I think that for a man women are a mysterious, unknown, foreign continent. Thirdly, I support all the claims of neo-feminism, because to say that it is a distant and mysterious continent does not imply that equality has already been achieved or that there are no wrongdoings. For example, I have always thought that if I were a woman, sexual harassment would drive me crazy. Today there is an awakening in society to say 'enough is enough '. Women have the power and the right to say 'yes ' or 'no' or 'maybe '. That is a revolution.

Bernard Henri-Levy during the interview.

- Interview with Bernard Henri-Levy - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

that God granted the world ten measures of beauty (yofi), nine for Jerusalem and just one for the rest of the world. The Holy City has no rivers, no sea view, no gardens. It is, rather, an ochre-hued stoney plateau set amongst valleys and dry riverbeds in the mountains of Judea. So what then is Jerusalem? Is it a concept, a wound, a state of mind? Jerusalem is two rocks and a wall. It's the custodian of the three symbolic stones of the three religions that derive from the same book: the Wailing Wall for Jews, the Holy Sepulchre for Christians and the Dome of the Rock for Muslims. One could say that its power resides in its promise of the cosmic, or its being the epicentre of stories about creation. According to Enrich Klein's 2005 account, Jerusalem has been destroyed 12 times, sieged 23 times, captured 52 times and recaptured 44 times. It is the only city in the world where history is both the past and also the future. Whatever our particular faith or whether we even have one or not, here is where its chaotic, propulsive energy is to be found.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

It says in the Talmud that God granted the world ten measures of beauty (yofi), nine for Jerusalem and just one for the rest of the world. The Holy City has no rivers, no sea view, no gardens. It is, rather, an ochre-hued stoney plateau set amongst valleys and dry riverbeds in the mountains of Judea. So what then is Jerusalem? Is it a concept, a wound, a state of mind? Jerusalem is two rocks and a wall. It's the custodian of the three symbolic stones of the three religions that derive from the same book: the Wailing Wall for Jews, the Holy Sepulchre for Christians and the Dome of the Rock for Muslims. One could say that its power resides in its promise of the cosmic, or its being the epicentre of stories about creation. According to Enrich Klein's 2005 account, Jerusalem has been destroyed 12 times, sieged 23 times, captured 52 times and recaptured 44 times. It is the only city in the world where history is both the past and also the future. Whatever our particular faith or whether we even have one or not, here is where its chaotic, propulsive energy is to be found.

Throughout history, a number of places have been venerated for their holiness: the Ganges and its passage through Benares in India, the Valley Of The Kings in Egypt or the tomb of the poet Hajez in Iran. They are all realities. Nobody is denying this. But Jerusalem poses myriad questions. Was it the Garden of Eden? Was it the cornerstone on which the Arc of the Covenant would be built? According to Hebrew legend, the temple was erected on the exact spot where the waters of the Great Flood sprang. The rock was called Ebhen Shetiyyah, the Foundation Stone, and the first solid body in Creation as God separated the Earth from the primitive bodies of water. It may have been here where King David watched Bethsheba as she bathed, which led to him marrying her. David's mortal works and personal failings left God with no choice but to instruct him to not build the temple himself but leave the task to Solomon, his son with Bethsheba. In the Book of Chronicles, David confesses: “God told me: You will not build a house in my name because you are a man of war." The Wailing Wall, where Jews still pray to this day, is believed to have formed part of the temple wall.

Jewish Cemetery, as seen from the Kidron Valley

Awaiting The Redemption

The future can be guessed at by looking down on the city from the top of Kidron Valley or Josafat where the 3,000 year-old and largest Jewish cemetery in the world stretches out below. There is precious little space left among the 150,000 tombstones for new burials. For this reason, the last remaining outer rows have long been bought up, at unimaginable prices, by grand Jewish banking families now living in Manhattan. They want to be assured of their future place for the day when, according to the prophets, God will initiate the Redemption there. All are buried with their feet towards Temple Mount, in identical 120cm plots. On Judgement Day, God must find them all facing the right way.

Kidron Valley spreads beneath the cemetery and seperates the city from the three hills to the west of Mount Scopus, seat of Hebrew University, the Mount of Olives and Mount Scandal. Inside its walls, commissioned by King Soloman the Magnificent of his arquitect Mimar Sinan, the same architect who festooned Istambul with its most beautiful mosques, the Old Town is divided into four sections: Armenian, Jewish, Christian and Muslim. Four separate worlds sharing the same sun and the same God. Each one of them smells different - cardamom coffee, hookah tobacco, sweet breads, dried lamb's blood. From the Damascus Gate, one can see women laying out spinach leaves on rags in the street; flags with the Star of David (Palestinian never, they're banned); young girls selling peaches and cherries from wooden carts; monks calling the faithful to prayer at the nearby Al-Aqsa mosque; young women wearing veils; nuns in blue and white habits, priests in black, Orthodox Jews in kaftans and black hats, Israeli soldiers with their UZI rifles cocked, stray dogs. And rubbish. A lot of rubbish. Shells exploding, ambulances wailing, remnants of barbed wire.

The rest of the Old Town encompasses a constellation of holy places. Stringent visiting restrictions at the two most significant non-Jewish monuments, namely the Dome of the Rock and the Holy Sepulchre, were introduced in 2017, perhaps in anticipation of the tension about to escalate around them.

Restoration work

At the time of writing (January 2018), King Abdullah of Jordan is on a visit to the Vatican. He calls the Pope “My dear friend and brother” and gifts him a painting representing Rome, the Eternal City. The Hashemite dynasty are custodians of Jerusalem's holy Muslim sites. Also happening around this time is the culmination of seven years' restoration work on the 1,525 square metres of mosaics at the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa mosque. Out on the esplanade, Jordanian and Palestinian restorers worked away in silence, at a time when rage was making its comeback. The restored mosaics, which decorate the walls and vault of this famous octagonal building, consist of over 2 million coloured glass tiles with gold, silver and mother-of-pearl. Contained within the gilt ones, in their crystal soul, is a fine layer of real gold.

The Dome of the Rock is the oldest Muslim building in the world. It guards the stone of Mohammed who, because of his affinity with the Jewish faith, also held Jerusalem as the Holy City. According to a tradition heavily steeped in poetry, Mohammed received here the first of his revelations from the Angel Gabriel, who told him he was to be Allah's messenger. Years later, Gabriel was to appear again, bringing the white horse, Buraq, which carried Mohammed at lightening speed to a sacred rock on the top of Mount Moriah. This was a key place in Hebraic faith for being the stone upon which Abraham offered his son Isaac to God as a sacrifice. From there, Mohammed ascended a staircase of bright light to the Seventh Heaven where he was proclaimed superior to the Old Testament prophets. This journey to heaven is remembered in Sura 17 of the Koran entitled: "The Children of Israel". When Caliph Omar arrived in Jerusalem in 638 AD CE, six years after Mohammed's death, he built a wooden mosque that would later become Al-Aqsa. Mohammed's heirs established their capital in Damascus and decided to make Jerusalem a place of pilgrimage as important as Mecca and Medina. They confided in Byzantine, Greek and Egyptian architects to build a stone cupola for over the sacred rock of Mount Moria; an octagon with with twelve interior columns and four piers supporting the golden hemisphere. These were the sacred shapes and numbers of Eastern religions. The smaller Al-Aqsa mosque, at the extreme southern end of the platform, was given a silver dome and gold and silver doors. These two sanctified structures were to become magnets for the faithful.

Interior of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Renovation of the Holy Sepulchre, which was completed in March 2018, freed the edicule from its corset of iron girders, a scaffolding that had constricted it since 1934. It can now be seen exactly as it was conceived in 1810. A team, led by the Athenian Antonia Moropolou, are unanimous in describing the most exciting moment of the nine months the restoration work lasted, as the removal of the marble cladding protecting the rock bench where Christian tradition believes the body of Jesus Christ lay. Through a tiny door in the Chapel of the Angel, antechamber to the tomb, a glass panel covers the marble slab, leaving the original rock of the tomb inside exposed.

The "Day of Rage”, December 2017. Streets of Ramallah.

The "Day of Rage"

The front pages of newspapers across the world went with various different analyses of the same photograph. A young man hurls a stone with his sling as a battle rages on around him. These were the streets of Ramallah on the "Day of Rage", so named by Hamas in order to fire up Palestinians against Trump's decision, the previous December 6th, to recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and his decision to move the US embassy there from Tel Aviv. The young man in the photo has his face covered by the keffiyeh of a new intifada and his gesture is one of hate. He's the present-day Discobolus, a discus thrower of the Instagram era. The expansive curve of his stone throw is already turning into a spiral of violence. Neither side wants to lose their children again.

Seventy years ago, the United Nations agreed a plan to partition Palestine, which had been under British mandate since the end of the First World War. A little over half the territory was assigned to the Jewish state, as proclaimed officially in May of 1948, and the remainder was envisioned for a future Arab state. Jerusalem would be accorded corpus separatum status, a separate entity under international jurisdiction. But the war waged between the Jewish forces and Arab countries, until the armistice of July 1949 was signed, put paid to the UN's plans. The west of the city was occupied by Israel, establishing its capital there, and the east remained under Jordanian jurisdiction, as well as the West Bank. The Green Line of ceasefire dividing the city with barbed wire and barricades lasted until Israel's victory in the Six Day War of 1967. Since then, even her closest allies have maintained their embassies at a distance of 70 km.

Jerusalem is simultaneously glory and sin. Many are the writers who have left their mark on the palimpsest that is Jerusalem. From the 16th century travel guides, now decorating the display cases of the National Library in its Urbs Beata Hierusalem exhibition, to the words of Chateaubriand; "I stood, staring at Jerusalem, measuring the heights of its walls, memories from history all the while coming to me ..... Even if I lived to be a thousand years, never could I forget this desert that seems still to breathe the greatness of Jehovah and the terrors of death".

Measures of sorrow

However, claims The Economist, that aforementioned distribution of measures of beauty (yofi) from the Talmud might at times seem erroneous. And what if it were instead measures of sorrow that God gave the world? Nine for Jerusalem and one for the rest?

There are two instances of this in the city today. Yad Vashem is one of the most impressive museums in the world. Its objects, photographs and videos underline Man's capacity for creating destruction among his counterparts. One is Jerusalem's Holocaust Museum, 180 square metres of passageways and galleries charting the history of the extermination of six million Jews during WWII. Located on the Hill Of Remembrance, Yad Vashem was founded in 1953 by an act of the Israeli parliament. Moshe Safdie's building is astounding. A triangular prism seen to penetrate one side of the mountain and come out the other. The visual sensation is unique: a base in almost darkness but a sky lightly illuminated. Physical death but also spiritual life. "And to them will I give in my house and within my walls a memorial (Yad) and a name (Shem) that will never be cut off." Isaiah 56:5. Yad Vashem won the Prince of Asturias Award for Concord in 2007.

Yad Vashem Museum

A few metres away, and as if a continuation of the message, is Hadassah Hospital housing the world's largest skin bank. It has existed since the days of the years-long Second Intifada when the casualty figures screamed nearly a hundred suicide bombers, 5,000 dead and tens of thousands wounded, many of them burns victims. Here are kept, frozen in liquid nitrogen, 170 square metres of human skin, which is enough to treat about 100 people with 50% burns to their body. Jerusalem is all divisory lines, Vias Dolorosas, border posts and walls ~ much like Doris Salcedo's Shibboleth, a 546 foot-long crack in the cement floor of the Tate Modern, its 'scar' still visible today.

And its writers

Finally, Jerusalem today is also its writers. Amos Oz, A.B. Yehoshua, books such as To The End Of The Land and real lived experiences, too. The eulogy that David Grossman read out at the funeral for his son Uri, 21, killed in combat by friendly fire in August 2006 when his jeep got hit by a Hezbollah missile, explains one way of living with a kind of severe serenity when surrounded by a sea of enemies. "For three days, every thought began with: "He/we won't". He won't come, we won't talk, we won't laugh ... Israel will have its own reckoning ... and we will act against the gravity of grief."

View from inside Yad Vashem Museum

Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

On the occasion of the Madrid Book Fair, Mario Vargas Llosa talks about his latest publication, "The Call of the Tribe", an intellectual and political essay on the philosophers and authors who have shaped his thinking. Which book from current Spanish literature would you most highly recommend? Out of all I've read lately, perhaps the most interesting would be Javier Cercados' "The Impostor".

Autor: Elena Cué

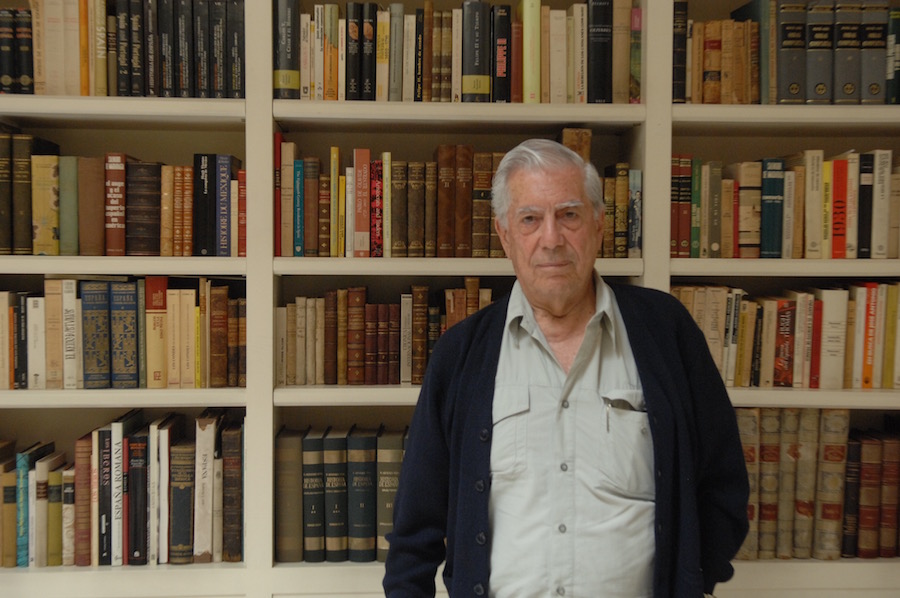

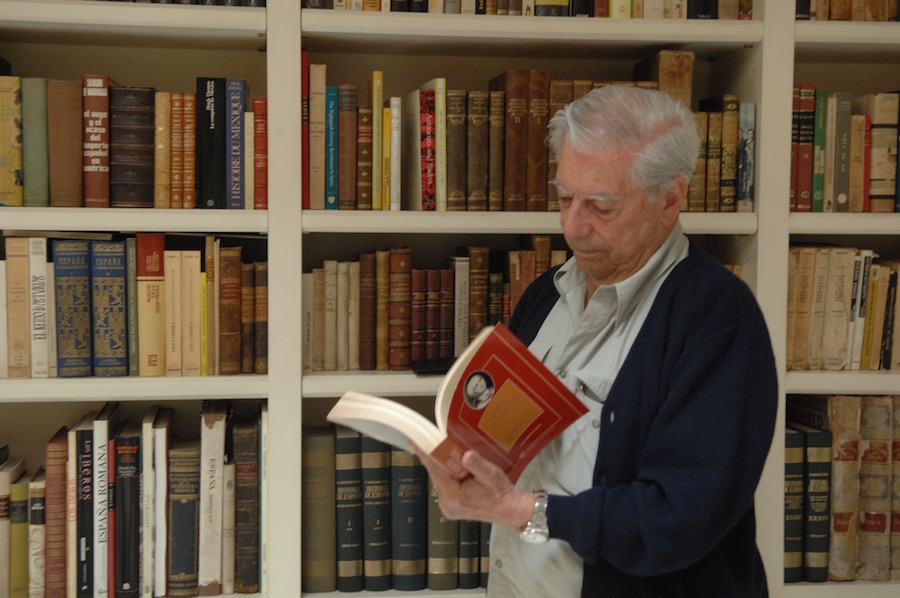

Mario Vargas Llosa. Photo by Elena Cué

On the occasion of the Madrid Book Fair, Mario Vargas Llosa talks about his latest publication, "The Call of the Tribe", an intellectual and political essay on the philosophers and authors who have shaped his thinking.

Which book from current Spanish literature would you most highly recommend?

Out of all I've read lately, perhaps the most interesting would be Javier Cercados' "The Impostor". It's a wonderful book in that it is both a report that reads like a novel, whilst at the same time having as protagonist a character one would find hard to believe was real. It's a very entertaining and fun read.

In your latest book, "The Call of the Tribe", you present a staunch defence of liberal doctrine. With regards to the media today, how does one reconcile freedom of expression with fake news?

I think that is one of the biggest problems of our time. We're seeing a real revolution in the field of communications but this, instead of spreading the truth about what is happening in the world, has allowed fiction to infiltrate the media making it now very difficult to know what is true and what is seemingly true, but false. These are the famous post-truths of our time.

Elon Musk said recently that he wants to create a service - something like a qualification agency - in order for readers to be able to ascertain the journalistic rigour of any writer or media outlet. How would you feel about that?

I wish there were a reliable, valid way to reference and rate the media in terms of their truthfulness or falsehoods. As human beings, we are totally confused as regards the media today. They're pulling the wool over our eyes with the greatest of ease. Nevertheless, what's even worse is that there are nation-states with technology whose sole purpose is the dissemination of lies masquerading as truths. And this conspires tremendously against the very existence of democratic societies. Democracy is based on truth prevailing over lies so, if the boundary between these two becomes increasingly obscured and vague, it is democratic society itself that is threatened by this exaltation of those infamous post-truths.

So we are being played.

Freedom would disappear and people - come voting time - would often be basing their choices on facts that are completely false, exaggerated, distorted or, quite simply, blatant lies.

In your book, you talk about how you were an enthusiastic proponent of Marxism in your youth, but that you ended up distancing yourself from that ideology after witnessing, during visits to Cuba and the Soviet Union, how those ideas actually pan out materially. Do you believe that Liberalism helps more than Marxism to improve the lot of society's lower echelons?

Absolutely. One only thas to look at countries whose politics have been most effective in combating or eradicating misery and poverty, those who have created the best living conditions for all of its citizens. There isn't a single Marxist country among them. The countries that have attained the highest standards of living are democratic ones that apply liberal-style policies, as is the case with the Nordics, for instance, or Switzerland, etc. In Asia, the most developed countries are already democracies or ones that have been leaving authoritarianism behind and increasingly approaching what are now liberal and democratic societies.

Marxist countries, on the other hand, have been disintegrating and disappearing one after another and not because of any external intervention but because of the absolute inability of their institutions to meet the most basic needs, desires and illusions of any society.

Why did the Soviet Union fall?

The Soviet Union fell not because it was attacked. It collapsed because of its own inability to create a modern, efficient society offering full employment and an acceptable standard of living.

Why did Communist China suddenly become a Capitalist country?

That also happened because of China's collective and state inability to create employment and acceptable living conditions for all of its citizens. I think this is the most conclusive and definitive proof that Socialism, of the Communist variety, doesn't work.

Adam Smith, Popper, Hayek, Ortega y Gasset, Raymond Aron, Isaiah Berlin and Revel are the seven liberal thinkers who feature in your book. Is there something they all have in common?

Their tolerant attitude, their admission that, rather than being invariably self-evident and obvious, the truth is often vague and obscure and that, therefore, many mistakes can be made. Also, that what must always be fought against in the field of politics is dogmatism or the authoritarian imposition of specific principles or particular methods. In this field, I believe Liberalism has always been a doctrine of absolute tolerance and this tolerance is its best defence against violence.

Does Hayek's Neoliberalism have anything to do with the modern, more radical version?

Hayek has been on the receiving end of much criticism for having, shall we say, such an unshakeable faith that the free market would solve practically every problem and he is attacked as an extremist for it. There is some truth to that. He would often exaggerate his beliefs and even held some that I found to be absolutely false, such as that there was more liberty in Chile under Pinochet than under Allende. I think that was an outrageous comment for which he was roundly and rightly criticised. To think that a dictatorship that kills people or enforces press censorship can be more free than a democratic society, albeit an extremist one like Allende's, seems patently wrong to me.

Where would Liberalism fit in?

There are tendencies at the moment that come very close to Liberalism. Social Democracy, for instance, often verges on it. But then there are aspects of Conservatism that also border on it. Actually, I quote the case of Thatcher and Reagan who were both conservative leaders but who nevertheless made unreservedly and deeply liberal economic reforms which brought numerous benefits to their respective countries. So I think Liberalism is made up of many different nuances, all of them with laws and reforms that are open to criticism, fostering the potential improvements and systematic refinements that Popper called permanent reformism. Ultimately, this is the doctrine that has allowed countries to achieve the best methods for economic and social development, as well as democratic tolerance.

Do you agree with Hayek that intellectuals are the enemies of liberty because they are so detached from industry and commerce?

Unfortunately, twentieth-century intellectuals have demonstrated an extraordinary level of political blindness. First and foremost for not seeing how reality was so far removed from the grand illusions of Marxist socialism and, lastly, because they have contributed more than anyone else to devaluing democratic principles and presenting democracy as the mask of exploitation and colonialism, etc, something that democracy has never been. That is precisely why the attempt at attaining paradise, as proposed by Marxism, led, ultimately, to the creation of sheer hell on earth. By contrast, democracy doesn't aspire to build a heaven on earth but rather it hopes to create a system with the potential for near-perfection via periodic reforms to improve progress towards combating major issues like unemployment and health with ever greater efficiency. And this is a reality that is borne out by facts because the most advanced, least imperfect societies are democratic or, in other words, liberal ones. It's true that democracy isn't perfect. There's been corruption at its heart, without a doubt, and that's the reality. But the most imperfect democracies are still preferable to the most perfect dictatorships, always.

In a world where wealth production has become the principal value, what do you think is the function of the intellectual today? Should intellectuals play an active part in society and politics?

I think participation is a basic democratic principle. If you don't take part in public debate then you have no right to complain, not even if you're only doing it in writing. There's nothing that destroys language as much as politics does because politics is about soundbites, set phrases, sayings that don't express truth or reality. In this area, intellectuals have a really important role to play. Also, on another level, I think a society without ideas is one that is condemned to die.

Where should these ideas come from?

Ideas come out of culture which is the great source, the supplier. So, in that sense, intellectuals should be like the seven thinkers in my book who have contributed, in such a decisive way, to the refinement of democratic doctrine and its institutions. Although, having said that, the ideal would be for intellectuals to differentiate between fact and fiction. There is a reality that can be perfect and that is the reality we create through painting, poetry, literature, etc. In that sphere, yes, perfection is achievable. Where it is not achievable is in the realm of politics or society. It's impossible for the whole of society to share the exact same values or to agree on what defines beauty or true pleasure or what the greatest achievements are. These things vary enormously depending on the idiosyncracies and personality of each individual. In this sphere, what's fundamental is that there should be great freedom for every individual to organise their life according to their own values and without compromising, damaging or erasing those of others.

In that respect, intellectuals shoulder great responsibility?

I believe so, yes. Take Sartre, for example. I was an avid reader and follower of his yet he ended up defending the Chinese Cultural Revolution which resulted in twenty million dead. On the other hand, the one thing I found compelling about Sartre was his stance on anti-colonialism. But then he went on to defend the Soviet Union and the Chinese Cultural Revolution which was one of the worst atrocities imaginable.

In your book, you don't just talk about Sartre ...

No, not only Sartre. How many other illustrious French intellectuals, like Roland Barthes, went to China? What was a sublime purist like him doing defending the killings and the horrific violence? The whole Tel Quel group went to China to pay homage to Mao and his Little Red Book. There's a contradiction there that's difficult for us to understand but I think it's that they were under the illusion that Communism would guarantee this perfect society and it would be like a great work of art, a masterpiece, a symphony. And, in the end, what did Communism do? It created hell on earth.

What do you think of the economic measures taken by Trump as regards bank deregulation, tax cuts and increased trade tariffs?

To a liberal, any decrease in taxation seems like a good move. But Trump's policies are completely contradictory because, on the one hand, they might well seem liberal but, on the other, they couldn't be further from liberalism, as in the case of border control and immigration. If you notice, this is very much at odds with the great American tradition of open borders. The USA is a nation of immigrants, a country whose grandeur arose from having opened its arms to the whole world and welcomed immigrants from practically every culture on earth and, thanks to what Americans call the "melting pot", integrating them into a society that really was the driving force for progress. I think Trump's policies go against that great, American, liberal tradition.

Moreover, it's really difficult to find either political - nationally and internationally - or economic coherence because of this constant contradiction. It's systematic confusion. For example, I think his anti-immigration policy is in direct conflict with every single liberal, democratic principal there is. Separating children from their parents is cruel, it's inhumane and it's in direct opposition to the spirit of democracy.

I would never have imagined that America, a seemingly advanced society, could choose a character like Trump, who is basically a populist. He's an unpredictable person.

Mario Vargas Llosa. Photo by Elena Cué

Three of the seven thinkers who appear in your book are Jewish and of those, Isaiah Berlin is in favour of Zionism and Popper is against. With regards to the current Israeli-Palestinian conflict, what are your thoughts?

What seemed to be the best solution was the two-state one. That had UN endorsement and there was a practically universal consensus that such a partition of the territory between Palestine and Israel should take place. At least half of the Israeli population agreed and there was this extraordinary movement called "Peace Now".

However, I think the critical moment was when Israel agreed to return 95% of the occupied territories and to accept Jerusalem as the capital of both Israel and Palestine. That Arafat rejected the offer was, I think, a very serious error of judgement.

Why?

Because since then, Israeli society has come to the conclusion - as hammered home by Sharon - that it isn't possible to reach an agreement with the Palestinians. This has made Israeli society increasingly reactionary and conservative while the pacifist movement shrinks day by day. In this sense, the tradition initiated by Sharon has been further radicalised by Netanyahu.

It's a situation that benefits no-one.

Absolutely. This state of affairs suits neither Palestine nor, to an even lesser extent, Israel. Israel is a country living in permanent danger, with constant military mobilisation and surrounded by enemies. It's also a country that's become very hardened, very violent and very militarised so it's become really difficult to defend Israel today after so many massacres. Granted, the country is very strong but you can't live in conditions like that. You can't live by requiring young people to do three years of military service. What kind of life is that

Reciprocal intolerance increases on a daily basis because, of course, on the Palestinian side the most radicalised forces are the prevalent ones. There's no solution in sight but what is clear is that this situation cannot continue indefinitely.

How would you rate Macron's first year as President of the French Republic?

I have a lot of time for Macron. I think he has liberated France from the clutches of fascist, extreme right factions such as the Front National and he has given French democracy back the youthfulness, idealism and dynamism it had lost. And not just French but European unity as a whole because he ran a campaign that benefited not only France but the European Union, also, which has since undergone an extraordinary revitalisation thanks to him. What's more, he's managed to bring people, who were otherwise absolutely estranged and fed up, back to politics. That's added a breadth and generosity to his politics. In a way, Macron has been the salvation of France at the time of crisis it found itself in, without a doubt.

In your book, you talk about "spontaneous orders", meaning those not personally determined by an individual but the ones that emerge spontaneously over time like, for instance, language, private property, commerce, markets. What would you say were the spontaneous orders of today?

Hayek believed in something quite fantastical - that the institutions which really prevail are not the ones created from power but the ones we carry along with us from the past. In other words, the ones that have survived the passage of time and new experiences, the ones that have demonstrated their ability to transform themselves over time and with time and tradition. These "spontaneous orders" are the best guarantee of prosperity a society can have. I think Hayek was totally spot-on about this.

Could women's rights, such as they are now, be among them?

Without a shadow of a doubt. Right now, we're seeing how this movement has gained traction and I think it's going to be a compelling one that will ultimately prevail on all levels, everywhere. Why? Because it's a matter of essential justice. Women, for the mere fact of being women, have been conditioned throughout history to be discriminated against, to be marginalised, and the time has come in humankind's evolution for this to no longer be tolerated. And it's not just intolerable for women. It's intolerable for any person with even a modicum of culture and sensitivity. This recent mobilisation towards gender equality is a magnificent example of a spontaneous order.

We complain about dumbed-down culture yet, at this moment in time, museums are full, tourism is massive, millions of books are published every year ... Is that another spontaneous order of our day?