If, in a nod to surrealism, Chema Madoz (Madrid, 1958) metamorphosed into something from one of his own photographs, it would most likely be a little turtle whose shell harboured a poetic soul. Since his first photographs in the 80's, of superimposed veins branching out over human forearms, his camera has never stopped capturing images of hum-drum, everyday objects as we've never seen them before coins, books, clocks, scales, tin-openers stripped of any and all superfluous connotations, objects whose reality he skews, sets free and offers to our imagination as simple signs, loosed from the chains of meaning. Madoz wants his images to slow us down and halt us in our tracks. He wants them so deeply imbedded in our minds and for so long that they become our very own. He wishes them "to always have something different to say to the person who wakes up with them on their wall every morning.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

If, in a nod to surrealism, Chema Madoz (Madrid, 1958) metamorphosed into something from one of his own photographs, it would most likely be a little turtle whose shell harboured a poetic soul.

Since his first photographs in the 80's, of superimposed veins branching out over human forearms, his camera has never stopped capturing images of hum-drum, everyday objects as we've never seen them before coins, books, clocks, scales, tin-openers stripped of any and all superfluous connotations, objects whose reality he skews, sets free and offers to our imagination as simple signs, loosed from the chains of meaning.

Madoz wants his images to slow us down and halt us in our tracks. He wants them so deeply imbedded in our minds and for so long that they become our very own. He wishes them "to always have something different to say to the person who wakes up with them on their wall every morning. To never wear out". And it was from this poetic wordplay, this expressivity, this expansion of meaning that his exhibition Chema Madoz 2008-2014: The Rules of the Game came into being. But also as a homage to the Renoir film of the same name.

While we wait for Madoz, who is patiently dealing with the media days before its inauguration at Sala Alcalá 31 in Madrid, we have a chat with the event’s organizer Borja Casani who tells us: "Chema's photos are, ultimately, the photographic portrait of an idea".

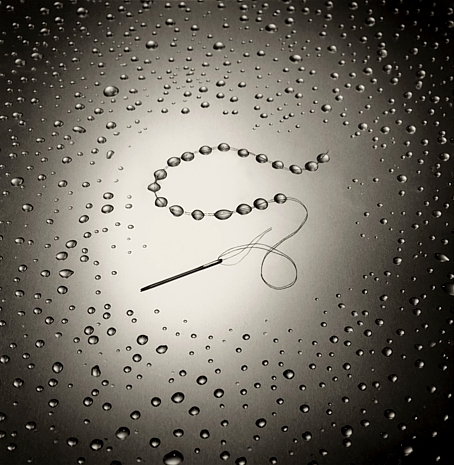

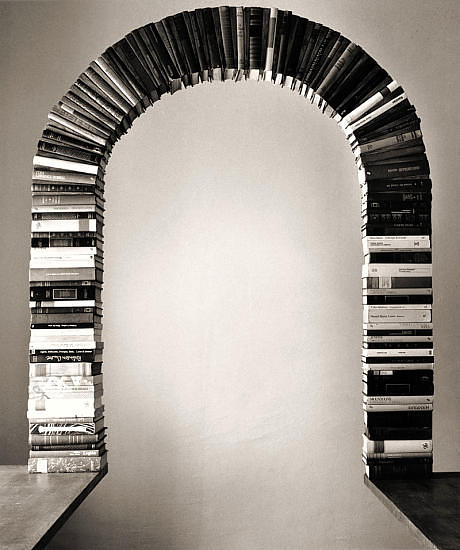

If objects had souls, Madoz would be the one to portray them. He is a seeker of simplicity. He lays all things bare, his aim being to achieve an image that is "austere, almost monastic in its frugality". That's his way of understanding beauty, interpreting it and then offering it to the spectator's imagination, divested of its usual meaning: books built up as the voussoirs and keystones of an arch, water droplets threaded onto a necklace of aqua pearls, a glass watch, an astral card, ... Casani goes on to say: "With Madoz, what you get is a hieroglyph that is already deciphered. He reveals to us a hypothesis and what then happens is that people feel comforted by the fact that they understand it. He presents us with objects we all feel familiar with. They're everyday items to an African, a European or a Latin American. And from this point of view, it's really satisfying to see Chema's success in so many countries. We've exhibited in, for instance, Egypt and people there understood. It's so gratifying, seeing day-to-day objects on display and communicating something to us."

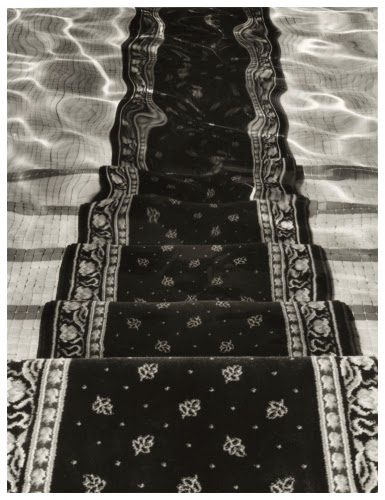

Madoz arrives and what strikes us is his gaze. Shy but scrutinizing at the same time, taking everything in, from top to bottom, fixing on and dissecting whatever grabs the attention of his mind's eye at that moment, lodging itself there, nagging at him until finally it makes its way into one of one of his sketch books in the form of a drawing. And from those pages into an almost surgical transformation on an operating table come carpentry bench where a woodwork square and tools become the sails of a toy boat or the grille bars of an iron door contort themselves into musical notes.

Madoz speaks slowly. He likes a slow rhythm. And silence. These are requisite traits in someone who observes the minute details differently, just as children absorbed in contemplation of an anthill invent a make-believe world around it. "I was an only child and I got used to playing all by myself very early on. I do like people but I need my solitude, too."

Following earlier exhibitions (Reina Sofia Museum, 1999; Telefonica Foundation, 2006) and Spain’s National Photography Prize (2000), the Sala Alcalá 31 exhibit is a compilation of Madoz's work over the previous 6 years, all invariably in black and white, analogue, and on baryta-coated paper, hung side by side under the dome of a basilica-like building that once housed a bank. Curiously, it was Madoz's first ever and much-despised job in a bank that caused the existential crisis that eventually freed him to devote himself full-time to photography.

The harmony of blacks, whites and greys along with the sheer Madrid sunlight flooding the gallery combine to create the very sensation of calm and silence that the artist intended. He would like his audience's attitude to be one of measured serenity, like the reading of a haiku. "This space is wonderful, if a little complicated by so many columns. What Borja and I tried to create here is a simple, elemental setting that "breathes", which I think, happily, we achieved with just the three divisions that permit a certain repose and tranquillity."

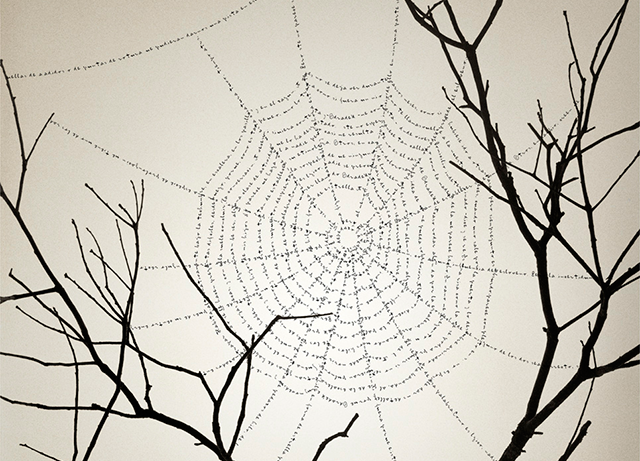

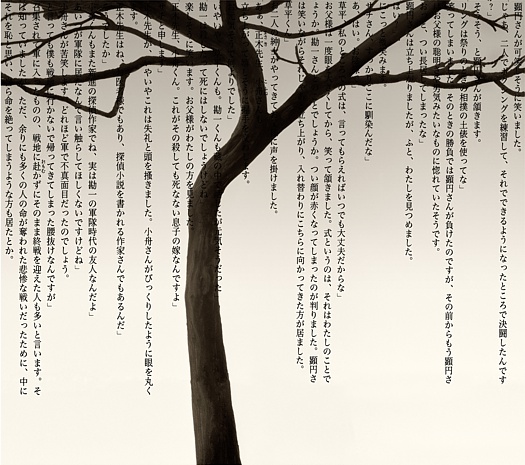

Whilst talking to us, Madoz is drawn to specific photographs and we follow him, observing his choices. There have been a few tangents during his evolution as an artist, albeit subtle ones because the crux of his language has always remained intact: everything hinges on and revolves around the object itself, and always will. However, in this exhibition, he adds or extends some personal obsessions, namely; his passion for calligraphy and the written word; the as yet timid appearance of some pencil drawings; and animal figures. Incidentally, over the course of his trajectory, he has dropped the human portraits from his field of interest due to the fact that, by stripping away their entire identity, their very selves, all he reduced them to in the end was a kind of pretext.

Now, though, he replaces them with mannequins: St Sebastian on a pillar, pierced by arrows that are better known to us as acupuncture needles or the two hollow, wax, pianist-like hands of a woman, their fingers twisting a thread of letters into a geometric puzzle; a reminder of that childhood pastime whereby two friends face to face, and their twenty fingers, manipulate one long piece of taut string into myriad patterns.

This latter photograph serves as the perfect example to ask Madoz about the very many ways his work could be interpreted. Echoing Joseph Beuys’ views on his approach to the creative process : "I've always been interested in creating images that don't 'wear out' even though they're constantly there, visible; images that, despite being viewed on a daily basis, keep enticing you back up close, again and again, making you re-possess them time after time. When you speak of that paused rhythm, that's the rhythm at which I approach the artists who interest me and whose work affects me on a very personal level. To think that your own work might have that effect on someone else is wonderful.” So we talk more about paintings. Madoz admits to a soft spot for Magritte: the clouds, the bowler hats … but also De Chirico and Morandi.

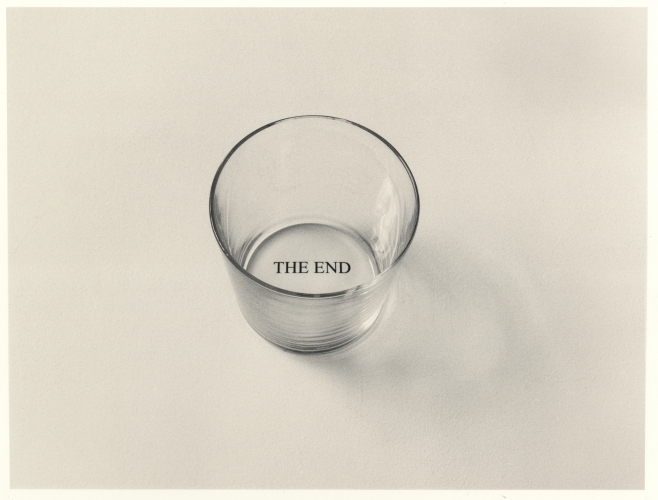

And then he confesses to another partiality: "There's one photo in the exhibition, just an empty glass tumbler on a white background and inside it is written The End. I think it's a lovely photo. The beauty of it and the glow of the glass really move me. And it’s that simplicity that leads, ultimately, to something beautiful. They’re very simple scenarios montages, lit from side on, the object effectively laid bare for us and within our reach. Nevertheless, it isn’t the beauty of a flower that’s being appropriated, or what is generally considered to be beautiful, or whatever represents the idea of beauty."

From painting, we move on to literature: "It's about the ability of verbal language to give us visual images. Gómez de la Serna would be, for instance, an obvious example but also Jorge Luis Borges, Bioy Casares, Boris Vian and Tanizaki. All of them, consummate writers with very personal imaginary worlds."

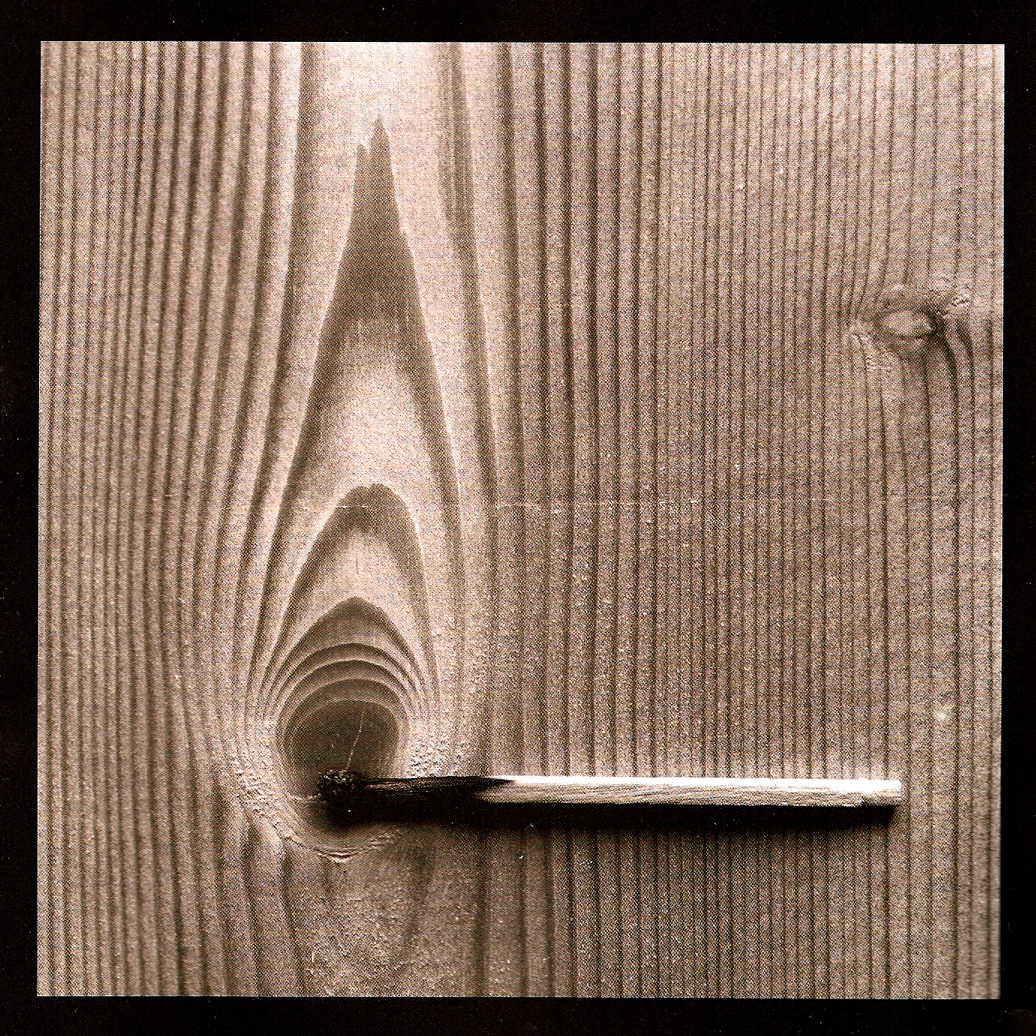

Madoz's studio is a suite of rooms not unlike a treasure trove or Borges’ The Aleph: “a point in space and time that contains all spaces and all time”, his micro cosmos of enough items and ideas to last him an entire lifetime. Out of them all, there's one to which he returns again and again and always will, one that plays on his mind in a never-ending loop: "Books. So simple, so quintessential, that rectangle offering so many possibilities, such varied interpretations and points of view, such depths of semantic richness. That's why you’ll find them so consistently and repeatedly throughout my life’s work. But I always get the sinking feeling that, maybe, one day, I'll run out of ways to use them, not because there are no other uses but because of my own lack of ability. I have my limits but the possibilities of the objects themselves are endless.” We stop now to face a picture of a map in which there appears to be the silhouette of a fish. It's one of his photos that have been heavily influenced by Japanese prints: "It's two negatives, one on top of the other; one is the map lit from above and the other is the fish sketch; and then I projected them both together." They start to resemble animals or animal shadows. Beside this is a picture of the grains and rings of a tree trunk marked out with letters, which confirms the importance of not only the written word but the whole realm of literature to Madoz. He never titles his work: "I have too much respect for writing. I well know a title can give a suggestive dimension to the reading of a piece. I, however, prefer not to give any clues at all and thereby give free rein to the spectator’s interpretative possibilities.”

The art of capturing an object’s essence begins, for Madoz, with the search for it. He is a regular at Madrid’s open-air flea markets where he often finds himself as if overcome by a feeling of stalking the prey that’s been snooping around his subconscious for some time previously. So what causes these “light bulb moments”? "It’s the mystery. I sometimes come across objects that are, essentially, weird. It’s more like them making me feel unsettled and confused. Something tells me to acquire them and make something of them and, generally-speaking, that’s what I end up doing.”

Madoz lives surrounded by the subjects he photographs, as does Kemal, the protagonist of Orhan Pamuk’s novel “The Museum Of Innocence”, who steals everyday household items from the woman he is stubbornly in love with only to make a museum out of them. Madoz, however, is not keen on following in the wake of the trend set in the 1920’s and 30’s by the likes of André Breton and, even more so, Marcel Duchamp during his ‘readymade’ period – a trend whereby the object gets top billing in the art world and has exhibitions to show for it. "I’ve always felt that photography places these objects in a much more attractive and interesting setting. Somewhat like a dream state. Something in your mind or on your mind that’s difficult to put your finger on, intangible. I really like that distance.”

He is well used to living with the objects he’s photographed. They are part and parcel of his predilection: "I’m surrounded by them in my studio. I store them there, often exactly as they were when photographed and sometimes as re-usable material. It’s quite amazing the significance and implications that objects have and how we endow them with powers of evocation. We associate them with life events, moments in time, people and ideas. For me, this was a huge discovery when I first started working with them. I remember once finding a badge I used to wear at school and I was amazed at how it transported me right back to my classmates, even my old desk …”

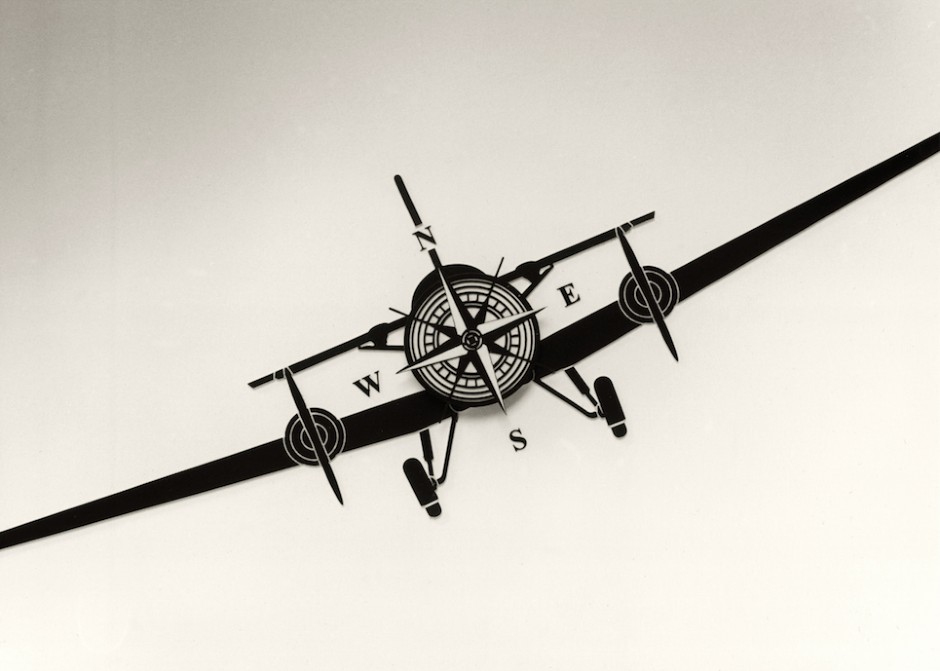

And so we finish our guided tour with the photograph that Madoz considers his most representative. It’s one of a lightplane seemingly made out of a child’s self-assembly cut-outs, black against a white background. Childhood here hinted at as a magical time of creation. On its propellers, Madoz has placed a compass: "At times, I identify with it. It corresponds to my mood; my being always on the move, somewhat disorientated.” And here is where our artist resides, between imagination and contemplation: Chema Madoz, a photographer of few words.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Chema Madoz. A photographer of few words - -Alejandra de Argos -