- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

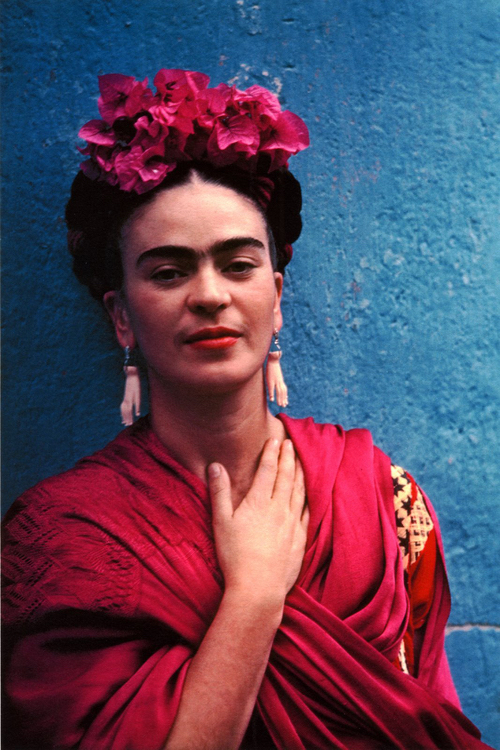

Marina Abramovic (Belgrade, 1946) is one of the greatest representatives of performance art today. Among her next projects are directing the opera Seven Deaths dedicated to Maria Callas in Covent Garden and preparing for her forthcoming exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, becoming the first living artist to exhibit in the prestigious institution after Hockney, Kiefer, Ai WeiWei and Kapoor. With the help of artist Adam Lowe she is creating the pieces for the exhibition. "I am 71 years old, in the latter years of my life and I am very conscious about making this transition. I think when you die you do not go into the darkness but into the light. What we are going to try to create is a way to make me disappear into the light. The artist tells me this before we begin our conversation while I observe some of her works with translucent qualities that allow us a glimpse of life and death at the same time.

Author: Elena Cué

Marina Abramovic. Photo: David Leyes

Marina Abramovic (Belgrade, 1946) is one of the greatest representatives of performance art today. Among her next projects are directing the opera Seven Deaths dedicated to Maria Callas in Covent Garden and preparing for her forthcoming exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, becoming the first living artist to exhibit in the prestigious institution after Hockney, Kiefer, Ai WeiWei and Kapoor. With the help of artist Adam Lowe she is creating the pieces for the exhibition. "I am 71 years old, in the latter years of my life and I am very conscious about making this transition. I think when you die you do not go into the darkness but into the light. What we are going to try to create is a way to make me disappear into the light. The artist tells me this before we begin our conversation while I observe some of her works with translucent qualities that allow us a glimpse of life and death at the same time.

You grew up in Belgrade where your parents occupied important posts in Marshal Tito’s Communist Regime. They were prominent partisans who fought in World War II against the Axis Powers and were later proclaimed as national heroes. How do these particular circumstances manifest themselves in you and in your art?

I have to add one more component, my grandmother. My parents were busy with their careers so they just left me with her. My grandmother hated communism and Tito. She was extremely spiritual so until I was six years old I spent most of my time with her in church. My great-uncle was proclaimed a saint so I had a family that mixed both the orthodox religion and communism which is conflicting in itself. I grew up in that contradiction and my work expresses it best. At that time, I was educated not to think about my personal life. I was taught everything that is important points towards a higher purpose in your life.

What lessons were those?

My mother taught me absolute discipline while from my father I learned about heroism and not to be afraid of anybody or anything. Later on, I needed to rebel against everyone and be myself. I took the heroism, discipline, self-control and spirituality and I started to become interested in Buddhism. A mixture of all these contradictions has been reflected in my work.

In your memoir “Walk through walls” you mention that you grew up in a violent environment due to the complicated marriage of your parents. Is there any relationship between those experiences and many of your performances where violence is present?

I was never actually interested in violence itself. I like to stage painful situations in front of an audience because we are afraid of pain, mortality and suffering in our lives. By understanding pain you free yourself of the fear of pain. This was the idea. In old cultures, every single ceremony involves physical pain as it is the door to elevated consciousness that opens your mind in a different way. Even if I cut myself in the kitchen while cutting an onion, I cry like a baby but in front of an audience the blood becomes the color, the skin becomes the canvas and the knife becomes an instrument. I completely transform it into something else.

Rest Energy (1980).

There is a therapy called "paradoxical intention" that consists of inducing the patient to face his or her fear as a method of healing.

This is absolutely how I see life! We pity ourselves and it is nonsense. We have an incredible energy inside ourselves but we just do not use it. What I do is show the public that if I can do it, they can do it too. I want to be their mirror. We are so much stronger, especially us women, because we have the power to create life. We seem weak but we have that incredible power so if we play the role of being submissive, fragile and servants to men, it is because their love is very important to us. This is why I never say I am a feminist. Why should I? I already have the power.

What differentiates real life from your performances?

It is complicated to explain but when you are in your normal life, you are one person and when you step in front of the public, you use the energy of the audience which you do not normally have. That energy gives you possibilities to transcend fear and do things that you would not have the energy, courage and strength to do otherwise. It can be applied to every performance. An audience of three hundred thousand people creates an enormous amount of energy that goes through you. When the curtain falls, you simply collapse because your own energy is not enough.

How do you channel your energy when you are not creating?

Amazingly! In every molecule of our bodies we have extra energy that we never use. We only use it in a moment of total danger. I learned how to use that type of energy in front of the audience without having any kind of danger. This is the transition you make from an ordinary-self to a super-self.

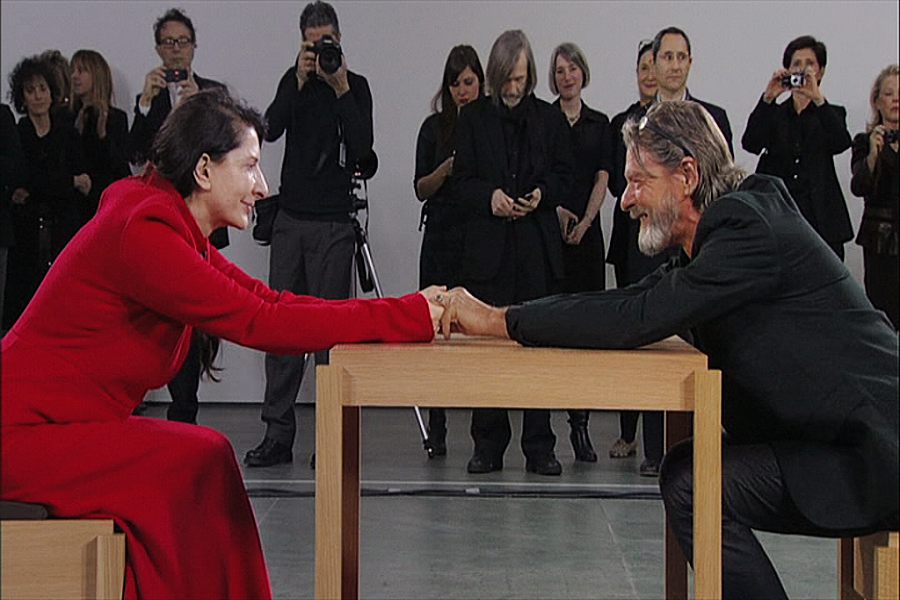

Reencuentro con Ulay en The artist is present (2010)

You discovered that your body was the tool you wanted to use to create art. What meaning do you give to the continuous exposure of your naked body?

The most natural state of the human body is the naked body, look at Adam and Eve. I do not really care about aging. I had a 70s performance in the Guggenheim for seven days. I was naked there and I was 60 at the time. We cannot escape the aging body. I started getting grey hair when I was 25 after the performance of Rhythm 0 when people almost killed me and since then I have decided I do not like gray hair.

What do you think about the concept of being the artist and the piece of art at the same time?

It took 50 years of my career for people to stop asking me why performance is art as it is not conventional. People tell you that you are a masochist, a sadist, an exhibitionist, that it is nonsense, not art. Performance art was only watched by your circle of friends. Now there are hundreds of thousands of people watching. Artist is present was seen by 17 million people on Facebook.

All great things require a lot of suffering and effort.

There is lots of sacrifice, lots of loneliness and lots of hell. You have to wake up every morning with ideas and know that your DNA is artistic. If we look at the history of art, it took El Greco 100 years, for instance, until people recognized him as an artist.

How was the transition from your very strict upbringing in Belgrade to the complete freedom of Amsterdam when you moved there at the age of 29?

It was hell because I was so used to restrictions as my work was built around restrictions and how to break them. In Holland, no one cared if you are naked or not. It was the hippy era and I was terrified as I did not know what to do with all that freedom. I had to construct my own restrictions for my work. It is very hard to sustain a career of 55 years because you always have to be as curious as a child, reinvent yourself and have the spirit of the time you are living in. I hate it when artists from my generation become tired, depressed and complain about art being dead. It is nonsense. Art is intrinsic to the human being, it is impossible for it to die.

What would you tell those artists?

I think that artists have to be erotic and sexual. They have to love food, life, relationships. That is what I love about life.

What about freedom?

Freedom is hard to achieve and you constantly have to recapture it. You have to make mistakes, learn from them and venture into new territories with the risk of getting lost. My favorite story is that of Columbus who discovered America by trying to find a new route to Asia. The fact that he embarked on that journey was more courageous than someone who went to the moon with the help of technology. Every human being should find a new way to discover their own America.

Columbus was going to the Orient but stumbled upon the West. Are you closer to the Western belief of the body-mind duality or to the Eastern belief, in which they form a whole?

Definitely the Eastern. You have to be harmonious. I think the Western approach is quite wrong because we never make an effort to understand what an extra sense of perception means. When we get sick, we just take pills but we don't look into the cause of why we are in that condition. The global view is much more interesting to me because mind and body go together. People either live only in their body and not in their mind or in their mind but not in their body. Western society is disconnected and technology is one of the biggest reasons for this. There is nothing wrong with technology, it is our approach that is wrong. We are addicted. We would spend more time playing video games or looking at computers than communicating with another human being. This is why I created “The Abramovic Method”. I provide the public with sound-blocking headphones and lockers to put their electronics away. Once there was a 12-year old who put the headphones on and told me they are not working. He had never listened to silence.

Marina Abramović y Antony en The Life and Death of Marina Abramović, www.robertwilson.com

What does such a spiritual person like you believe in?

I don't believe in Gods or religion. I really believe in energy, in divine spirit. I believe in the kind of enlightenment where you experience a complete purification of your mind and body and you lift your spirit to another level. I saw it and experienced it myself so I really believe in it.

Your art emits a lot of sexuality. How and to what extent is sexuality present in your art?

There is not just one aspect to my work there are so many layers: a social aspect, an erotic aspect, a disturbing aspect, a political aspect. I think eroticism is so important because the main energy we have in our body is sexual. Then it is up to us how we transform this sexual energy. It can be transformed through violence, war, killing, tenderness, love or spirituality. It depends how we use that energy but the fundamental, raw energy is a sexual one. Sex is as important as food. You have to eat well, have good sex; you have to live life in every single moment.

What about love?

Love has always been important in my life. I always fall in love with the wrong people, I get disappointed then I do it again. Right now I am with someone who is 21 years younger than me and it is so great that I cannot believe it is true. In our society, it is always acceptable for the woman to be younger but not the other way around. My role model is the French president’s wife who is 25 years older than he is. The press cannot accept it so they have to make him look homosexual. Society cannot accept that women can be older. I don't care about these rules. My boyfriend told me he forbids me to die before him. Love makes you so vital, so happy. Women who are 70 think everything is dead which is not true at all. The best erotic life I have had was after the menopause. So yes, sexuality is important. In my 20s, 30s and 40s I was criticized for my art, especially by men. Now in my 60s and 70s I am criticized by women. It is amazing that they think you are not supposed to look good and feel happy when you are 70. It is incredible how much hostility there is. I have always been out of the box and I will always continue to be that way. Although this is not allowed because society wants you to be a certain way.

How do you fight that hostility?

One thing that is really important in a human’s life and an artist’s life is humor. You have to learn to laugh. In order to do that you need to learn to laugh at yourself first. You should not think you are the most important person in the world. You have to put your ego aside and be humble. We are all little grains of dust in the cosmos.

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

One morning in Paris, I meet with one of the great French intellectuals, philosopher and Minister of Education during the years of Jacques Chirac’s presidency of the French Republic, Luc Ferry (1951). Before delving into the transhumanist movement which led him to study biological science for three years and specialize in genome sequencing in order to write his book The Transhumanist Revolution, we begin by talking about his other books: Learning to Live or The Revolution of love, which has more than a purely reflective role; he describes philosophy as a tool in the search for a good life. “The idea has nothing to do with happiness as we generally understand it, but with the problem of making sense of life. The purpose of life in our historic moment is love”, he says. Happiness would therefore be the satisfaction of ethically fulfilling that which gives purpose to our life.

Author: Elena Cué

Luc Ferry

One morning in Paris, I meet with one of the great French intellectuals, philosopher and Minister of Education during the years of Jacques Chirac’s presidency of the French Republic, Luc Ferry (1951). Before delving into the transhumanist movement which led him to study biological science for three years and specialize in genome sequencing in order to write his book The Transhumanist Revolution, we begin by talking about his other books: Learning to Live or The Revolution of love, which has more than a purely reflective role; he describes philosophy as a tool in the search for a good life. “The idea has nothing to do with happiness as we generally understand it, but with the problem of making sense of life. The purpose of life in our historic moment is love”, he says. Happiness would therefore be the satisfaction of ethically fulfilling that which gives purpose to our life. He adds: “Love is both the foundation and at the center of family, it does not only affect our private life but the revolution of love, which is the sacralization of people and transcends to public life. Citizens request that the State protect their private lives because when we help our children, in reality, we are helping the future of humanity."

And now let’s continue by talking about your intellectual journey. Your latest book is titled The Transhumanist Revolution. What is transhumanism?

Transhumanism divides into two different fields: one is to improve and reinforce humankind as much as possible in the fight against old age and death. However, we will remain mortal as long as intelligence is incarnated in a biological body because sooner or later we will die. The other field is directed at posthumanism, the manufacture of a new species, a hybridization of man and machine equipped with a strong intelligence which is autonomous and practically immortal.

So the general concept of transhumanism would be...

It would be the transition from a therapeutic medicine to a medicine which repairs and improves.

What are we improving? What are they fixing?

It is a question of increasing life expectancy, making it possible for people to live longer and in better conditions. Transhumanists want to make people live for a hundred and fifty years, two hundred years, three hundred years, and I think it is great because there are so many women to love, so many books to read, so many languages to learn...To die at the age of one hundred is a premature death. Transhumanism aims to create a humanity that will be young and old at the same time, resulting in a youthful but experienced humanity.

What do you think about a future, like the one radical transhumanists describe, in which natural human inequalities based on genetic causes are eliminated, resulting in the modification of the human genome?

Thanks to biotechnology, the modification of an individual's genetic heritage is advancing. This modification would be one of free choice: “from chance to choice” thus meaning it would aim to correct natural inequalities. In order to correct social and economic inequalities we have created democracy, social protection, welfare and social security, which intend to diminish the differences between rich and poor. Now we have to match the conditions of those who have not been lucky by nature with those who have as they were born with very good natural qualities. In other words, if you have a child who is born with a disability or terrible illness, thanks to the biotechnological advances protected by transhumanism, the child would be able to live longer and in better conditions. Research on transhumanism started with rats at the University of Rochester in the United States and showed that, by modifying their genome, they were able to live longer. Their lifespan increased up to 30%. This proves that the project is possible.

What is your opinion regarding the most extreme type of transhumanism, that being post humanism?

Google’s Singularity University is developing the project of posthumanism by creating strong artificial intelligence. It consists of producing artificial neurons on a carbon-free silicon base. In fact, as the researchers are materialistic in the philosophical sense of the term, they believe that humans are machines, unlike Christians who believe that humans are composed of body and soul. For that reason, one day they will build a non-biological brain as for now it is only a matter of complexity that stands in their way. In doing so, they will create a post-humanity as they produce a technology that is similar to ours, with a conscience, the ability to apply free will, freedom, emotions, anger, fear, jealousy and love. A real brain will have been produced but on an immortal basis as opposed to a biological one. I do not believe in this because in order to have feelings you need to have a body, but post-humanity researchers argue that all feelings are found in the brain.

But how scary, if that were to be the case.

Although I don't believe in posthumanity, Steven Hawking, Bill Gates and Elon Musk do believe it will happen. In July 2015 they signed a petition with eminent scientists and researchers from around the world about the dangers of artificial intelligence becoming too strong. Musk believes it is the greatest threat ever invented by mankind.

I spoke to the most important person in the field, Facebook’s CEO of artificial intelligence, and asked him if he believes we are going to be able to produce this strong artificial intelligence, to which he replied it is only a matter of time.

So for me, there is no reason to fight transhumanism because everyone wants to live longer, have more experiences and a higher level of intelligence. On the other hand, posthumanism will be dangerous to humanity because we will turn into domestic pets, due to the superior capacities these hybrids will possess.

Everything we have discussed from the dangers of genetic manipulation to strong artificial intelligence suggests a need for ethical and political regulation. Are you optimistic in this regard?

I am not a pessimist but we will need regulation which will be difficult for three reasons. Firstly, it is very difficult for politicians to understand due to a lack of scientific knowledge. Secondly, research developments are made too quickly and consistently. And the third reason is globalization. If the regulation is only Spanish, German, French or Italian, it is meaningless as it only prohibits a certain number of things specific to one place and is not applicable to others. For example, insemination with the sperm of a stranger is prohibited in France but permitted in places like Belgium and the UK. This becomes useless and insignificant because it encourages medical tourism, therefore resulting in it being pointless to only restrict it in some countries. In our opinion, regulation should be universal, at least across Europe if not all over the world.

Do you think this research on genetic manipulation is done for altruistic reasons or as a money-making scheme?

Both! Just like the laboratories! I worked with laboratories for a long time and they earn a lot of money. Imagine that instead of an anti-wrinkle cream you can have a pill which destroys what we call senescence or old cells. These cells multiply in our bodies as we reach the age of fifty and cause grey hair, wrinkles and cancer. They make us grow old and get sick. Many biologists are working hard in order to find a way to destroy these senescent cells. Imagine how much money these laboratories and biologists would make if they were to create such a pill!

Absolutely! Instead of buying a cream, millions of women and men would prefer the pill.

It’s true. In addition to generating a lot of money, it will also greatly benefit society. Five years ago the biologist Raymond Schinazi discovered a medicine able cure the worst cases of Hepatitis C with a six-week long treatment with 98% success rate. This treatment was quite expensive and cost about $50,000 but it was wonderful because many people could benefit from it and recover. I believe people still want to live longer and therefore the benefits of investing in biotechnology are enormous. That is the reason why Google invests billions of dollars in biotechnology.

Have you spoken to anyone about the research into cancerous cells in an attempt to make them mortal again?

Yes, of course! It is very interesting. Google's activities are based on the artificial intelligence that deals with the genome or DNA responsible for sequencing cancerous cells. These cells are almost immortal when you try to kill them. Thus, once the DNA of a cancerous cell has been sequenced, it has information about its weaknesses and how to attack them. This method is called precision therapy or personalized therapy. After debating a lot with Google's CEO, he told me that cancer will be defeated in 20 - 30 years’ time thanks to artificial intelligence and advanced technology. Laurent Alexandre also shared that doctors will not be the deciding factor in this fight, but rather the computers. While the human brain takes 40 years to sequence the genome of a cancerous tumor, artificial intelligence does it in a minute. This makes it possible to detect the weaknesses of cancerous cells and attack them using effective medicine. Artificial intelligence has ramifications on collaborative technology and biology as well.

As you said in your book, collaborative economy has been made possible thanks to the infrastructure of the internet and its communication networks, with examples such as Uber, Airbnb, BlaBlaCar... How do you think this new economic organization based on sharing will affect a capitalist system like ours?

This is pure and simple capitalism! The novelty in the collaborative economy is that non-professionals can compete with professionals thanks to the technological infrastructure. It is a question of objects connected within a smartphone by only three things: artificial intelligence, big data and captor. The internet gives non-professionals, non-hoteliers, non-restauranteurs the opportunity to compete with professionals. This is Schumpeterian capitalism! Innovation makes it possible to compete with professionals, like Uber and taxis. In order to understand it further, you have to read Antigone by Sophocles.

What does Sophocles' work teach us about these start-ups?

There is a pattern of conflict between Airbnb and hoteliers, Uber and taxi drivers, or BlablaCar and car rental companies. All conflicts are violent, such as the conflict that confronts Antigone and Creon. Creon, the king of Thebes, says to his niece Antigone: "We cannot have a funeral ceremony for my nephew Polynices, Antigone’s brother, because he betrayed the city.” Antigone replies: "But he is my brother and I love him, so I don't want them to feed him to the dogs or birds, I want a funeral ceremony for him." This is the conflict between Creon and Antígone, who are both right. The Greeks consider this a tragic conflict because it is not between good and evil but between good and good. Airbnb is right! Hotels are right! It is a conflict between equivalent legitimacy. Airbnb's private shareholders say let us put our rooms on the market. While hoteliers say we have more regulations to comply with: security, fire, employees, social charges etc. It is an unfair competition. Both are right, that’s what is interesting.

What do your colleagues think?

French intellectuals are pessimistic regarding transhumanism. They stand against a collaborative economy and the new world that is just around the corner. However, the decrease in poverty in the world was the most notable achievement by the end of the 20th century. The world is much better today than it was before: there are human rights, women’s rights and democracy along with many other things that are improving. However, our intellectuals claim the opposite; they are not in favour of globalization, transhumanism, new technology and anything else in the sector of science and economy. The main objective of philosophy, before being about trying to understand the meaning of life, is in fact to understand the world we live in. There are two things occurring: the first one is globalization and new technology and the second one is revolution; a revolution of love and transhumanism that is changing our world. It is very interesting!

The philosopher Luc Ferry. Photo Elena Cué

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

Classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987, Venice now finds itself at death's door, not drowning in the Adriatic's high tides but suffocated by mass tourism. UNESCO has extended until December 2018 its deadline for Venice to meet twelve criteria, to the letter, that might spare it being added to the World Heritage in Danger List alongside Aleppo, Damascus and the historic centre of Vienna. Around 9.30 in the morning, crossing the Campo Santa Maria Formosa towards San Zaccaria, there is still a real feel of authentic Vienna with children on their way to school, kiosks piled high with bundles of Corriere della Sera and Il Gazzettino and the local dialect of young Venetians stepping off gondolas and vaporettos en route to the Plaza's fresh vegetable stalls piled high with basil, chicory, vine tomatoes and aubergines.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

Grand Canal, Venice

Classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987, Venice now finds itself at death's door, not drowning in the Adriatic's high tides but suffocated by mass tourism. UNESCO has extended until December 2018 its deadline for Venice to meet twelve criteria, to the letter, that might spare it being added to the World Heritage in Danger List alongside Aleppo, Damascus and the historic centre of Vienna.

Around 9.30 in the morning, crossing the Campo Santa Maria Formosa towards San Zaccaria, there is still a real feel of authentic Vienna with children on their way to school, kiosks piled high with bundles of Corriere della Sera and Il Gazzettino and the local dialect of young Venetians stepping off gondolas and vaporettos en route to the Plaza's fresh vegetable stalls piled high with basil, chicory, vine tomatoes and aubergines. A short distance away, a woman in her 70s sticks up for one of the few bookshops still trading: "We are afraid our city will become the Las Vegas of the Adriatic" she says, pointing to a single book that seems to be crying out from the window display ~ If Venice Dies by Salvatore Settis. It's to the voice of this former professor and director of the Getty Centre of Arts in the 90's that Venetians cling. Settis implores and challenges us with the urgent question: "How much longer can La Serenissima survive tourism?"

Campo Santa Maria Formosa, Canaletto (1735)

Three ways to fall

Cities, according to Settis, die in one of three ways. By enemy destruction (see Carthage, razed to the ground by Rome in 146 BC); by an invader force ousting the indigenous people and their gods (see Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, annihilated by the Spanish in 1521); or because the inhabitants of that city gradually lose their memory and their dignity and abandon themselves to a slow amnesia (as happened in Athens). After the glory of the classical polis, that of Pericles, Phidias, Sophocles and Aeschylus, Athens first lost its political autonomy, then its cultural initiative and then, little by little, having sleepwalked through centuries in its marble whiteness, saw itself devoured by darkness until nothing at all remained of its identity. Only in 1827 did it awaken again by dint of a coup of independence.

The facts should mobilise us against such oblivion. Venice hosts 28 million tourists a year. That's four visitors per day per resident. The toll of this has been the systematic depopulation of the city. Only once before has Venice suffered a decline comparable to the current one and that was during the bubonic plague of 1630. The number of inhabitants has gone down from 174,808 in 1951 to 55,000 today. Compare that to the 66,000 tourists per day.

Venetians no longer want to live in Venice. Around 1,000 residents a year leave the city, a city with "the finest parlour in the world" according to Stendhal but which is becoming increasingly wilted and stagnant. Houses have become hotels. The proliferation of AirBnBs has meant a steep rise in rents. WiFi hotspots now outnumber the delicatessens that once sold prosciutto; the trattorias on the lively banks of the Zattere have closed down while young tourists in shorts and a rucksack crowd the bridges eating take-away spaghetti carbonara with chopsticks. Twenty years ago in the Rialto district, Venetians made their living selling each other fresh fish and artichokes. There was also a plethora of workshops making and selling Murano glass and masks to travellers who knew what they were buying and what it was worth. That Venice no longer exists. Nowadays, Chinese merchants sell Venetian masks made in China to Chinese tourists for one euro a pop.

Also now, while tourists queue for hours to go sightseeing at the Doge's Palace, the fascinating gallery exhibitions rekindling the glory of the city sit empty of visitors. John Ruskin's The Stones of Venice (Doge's Palace), Bellini/Mantenga (Querini Stampalia Foundation), Dancing With Myself (Punta della Dorada) and the 16th Architecture Biennial, to name but a few.

Monsters Of Steel

Venice, once the seat of great maritime and trading power, is in grave danger of being inundated by sea monsters weighing over 55,000 tonnes making their way up the Giudecca channel spewing out 1,500,000 passengers each and every year. The MSC Divina cruiser, for instance, is 67 metres high, twice that of the Doge's Palace. Every time one of these floating cities squeezes itself between the river banks, darkness obscures the alleyways and bridges of the Dorsoduro district, as if they were under a total eclipse of the sun. In June, some 25,000 residents took part in a local referendum, albeit without legal import, calling for a ban on these ships entering the waterways. Something quite unthinkable for the powerful lobby group of hotels, shops and rental agencies. In Venice, tourism essentially provides a living to 30,000 Venetians.

The debate has intensified since Prague, Amsterdam, Lisbon, Dubrovnik, Seville and Granada were likewise invaded by hordes of tourists. “Tourism-phobia is a cry of desperation by residents" insists the journalist Pedro Bravo in his 2018 book Excess Baggage. "We assume that the sum total of all tourist expenditure goes straight to the city in question but this is not the case. The tour operators keep between 40% and 50% of the money involved so the destinations hardly benefit at all but it is these latter who, nevertheless, are lumbered with the extra costs of policing, cleaning, hospitals and infrastructures". In the case of Venice, the situation is exacerbated by its island status and its size.

Dorsoduro, Venice

Head-to-head confrontation

The Venetian lagoon is the result of fifteen centuries of human intervention in the search for a balance between its needs and those of nature. It is forced to defend itself against the tides that flood through the three entry points and sink it lower time and time again. Venice has been at times Byzantine, Austrian and Napoleonic. The Doge's betrothals were played out from the sea in a procession of gondolas and sailboats to the Lido on the Feast of the Assumption. He brought the body of St Mark all the way from Alexandria, buried it under the Pala d'Oro of the Basilica and established the lion as state symbol.

View of St Mark's Basilica from the Doge's Palace, Venice

“The city that baffles the world" is an interdependent, organic set of buildings, communication systems and structures. A tapestry of logical threads connecting art, history and tradition and that is how we should view it.

In his famous Plan of Venice of 1500, Jacopo De' Barbari was already mapping the latticework of secrets under the current of canals and the division of the city into six sestieri neighbourhoods, representing the six teeth of the "ferro", the iron fixtures adorning the black prow of gondolas. But La Serenissima is not just synonymous with beauty. Behind the so-called "Glory of Venice", there was a power without which we Europeans would not be the same people we are today. Venice is the syncretism of East and West, it's Marco Polo, it's the island that ignored feudalism, it's commerce, music, the Arsenal heart of the naval industry, the boats and ships, the saviour of the classics since the time of Plato and Aristotle. It's Petrarch, the Marciana Library, the Aldo Manucio press. It's also the Battle of Lepanto, the architecture of the Palladium, the paintings of Carpaccio and of Bellini and Titian, the San Rocco monastery decorated with Tintoretto's most celebrated pictorial cycle of paintings.

And so, Venice appears to us as an insistent set of reflections. Marcel Brion wrote of it ~ "Beauty doesn't make its entrance until that moment when one has nothing left to fear in one's life".

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

The ending of Paolo Sorrentino's film The Great Beauty is one long, slow take over the River Tiber. The aerial camera rolls, at bird's eye height, from one bank to the other, flying over couples out for a summer stroll, or sometimes at one with the channel of water, crossing through the dark eyes underneath bridges or resting on streetlamps lit for a Roman sunrise. The very last scene in this serene finale takes us up close to the Sant’Angelo Bridge. Before the screen fades to black, Sorrentino abandons us on one of the angels that Bernini ideated to decorate this bridge connecting the Vatican with the Tiber. And from there, we call to mind what this city of popes, this epicentre of the 17th century world means for us as we marvel at the works of a unique man with the Eternal City always on his mind.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

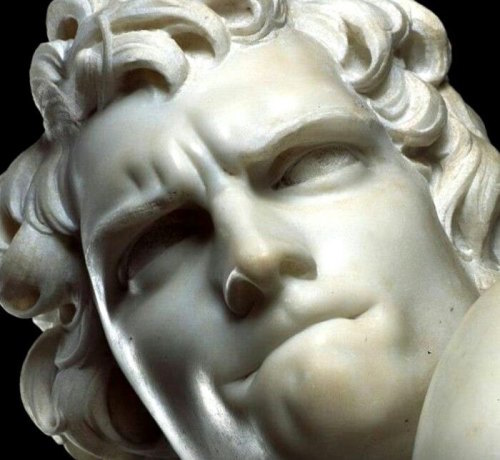

The Rape Of Proserpina (detail), 1621-22, Borghese Gallery, Rome

The ending of Paolo Sorrentino's film The Great Beauty is one long, slow take over the River Tiber. The aerial camera rolls, at bird's eye height, from one bank to the other, flying over couples out for a summer stroll, or sometimes at one with the channel of water, crossing through the dark eyes underneath bridges or resting on streetlamps lit for a Roman sunrise. The very last scene in this serene finale takes us up close to the Sant’Angelo Bridge. Before the screen fades to black, Sorrentino abandons us on one of the angels that Bernini ideated to decorate this bridge connecting the Vatican with the Tiber. And from there, we call to mind what this city of popes, this epicentre of the 17th century world means for us as we marvel at the works of a unique man with the Eternal City always on his mind.

Sant’Angelo Bridge, Rome

Rome is currently celebrating the 20th anniversary of the re-opening of the Borghese Gallery with an exhibition dedicated to Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680), the last of the great, universal masters who made Italy the artistic heart of Europe for over 300 years. Not only was he the greatest sculptor of the 17th century, he was also an arquitect, painter, dramatic author, and, above all, the director general of papal Rome, a Rome that would be required to endure until the present day and to remain the most grandiose show of urbanism ever attempted. Bernini served under eight popes in this most Baroque of cities, a style that grew out of the triumphal catholicism of the Counter-Reformation. By 1600, Italy had already gone through many uneventful centuries when suddenly, in the space of a hundred years, it becomes more active than ever before. But why and how does Italy embody such artistic genius in its most absolute form time and time again? What is the mystery surrounding this small Mediterranean peninsula located between Spain and Turkey? What is its secret recipe for churning out artists of calibre from Giotto to Modigliani? What is the link between politics, the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation?

Let's take a closer look at the ten angels sculpted by Bernini between 1668 and 1669 when his entire oeuvre was dedicated exclusively to works that were full of emotion. The windswept Sant'Angelo Bridge angels are disconsolate between the clouds above and the solid, cylindrical Sant'Angelo Castle, with a black angel at its pinnacle, as a backdrop. In his latter years, Bernini, more than ever before, used the movement of robes such as theirs as a language with which to convey feeling.

The Sant’Angelo Bridge was built to connect the two banks of the River Tiber in the 1st century AD. In the Middle Ages, it gave access to the Vatican City. Since the 17th century, Bernini's sculptures have left the pilgrims crossing it open-mouthed with wonder. It is a matchless means of approach into the oval arms and colonnades of St Peter's Square, the bronze Baldechin ceiling, the spiritually-awakening Roman centurian Saint Longinus who had speared the crucified Jesus, the Throne of St Peter symbolic of the new Ecclesia Triumphans (Church Triumphant) and so on.

St Peter's Basilica and Square, Vatican City, Rome

In the 17th century, the power of Rome and its popes was unbounded. The Catholic Church, despite having lost some of its territories, gained a renewed sense of triumph after saving itself and its dogma from herecy. The new popes converted their desire for power into a spiritual empire, believing themselves the heirs of Roman emperors. St Peter's was their work and Bernini their right-hand master artist for 57 uninterrupted years. When our young sculptor, not yet 30 years of age, received and accepted Pope Urban VIII's commission to complete St Peter's, it was a challenge and a feat that, one could say, surpassed that of replacing the Twin Towers in New York after 9/11.

David (detail), 1623-24, Borghese Gallery, Rome

Bernini at the Borghese Gallery

Adding to Cardinal Scipione Borghese's already unrivalled collection, his eponymous gallery, set amongst gardens, lemon trees and fountains between Popolo Square and Mount Pinzio, is currently exhibiting almost all the paintings ever attributed to Bernini. Also on display and facing each other are his two bronze Crucifixions which are both normally housed outside Italy, one in Madrid's Escorial Palace and the other in Toronto. But, more especially, there are his greatest busts ~ the first and second versions of Scipione Borghese and that of Constanza Bonarelli.

Bust of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, 1632, Borghese Gallery, Rome

Bernini brought about a total transformation in the sculpted portrait, taking it out of Renaissance immortality and breathing new life back into it. He was a prodigious craftsman who learnt the trade from his sculptor father. He never attended school, never studied Latin and, since childhood, had escaped from his chores and work in Santa Maria Maggiore to what was his one true place of learning ~ the Vatican Museums. There, he would study works such as the Belvedere Torso or the Apollo and draw out his first sketches. However, in addition to his talent as a draughtsman and his technical mastery, Bernini's head also harboured the "concetto", the idea or the concept. It did not matter whether it was for an opera set or a village square. One of the "concetti" that obsessed him was to challenge his materials and make them exceed their limitations. To work at the whiteness of the marble until it appeared coloured. To invent unruly manes of hair speckled with shadows or deep beards like foam on the ocean waves, trepanning and chiselling away at his pale materials, the hands of Gods sinking into the flesh of a nymph or tears running down a cheek ... in such a way that he aspired to imbue cold, inert stone with movement and life.

Apollo and Daphne (detail), 1622-25, Borghese Gallery, Rome

Letting the city yield its mysteries

In Alejo Carpentier's preface to Love For the City, he writes: “To roam a city is to retrace it, deconstruct it and look at it until it yields up its mysteries." This exhibition also offers us an exciting second dimension whereby we discover Bernini's signature stamp throughout the rest of Rome via the ecstasies of his sculpted saints in church chapels, in the bronze stolen from the facade of the Pantheon to construct the Baldequin ceiling, in the heraldic bees from the Barberini family's coat of arms that embellish gods of mythology and funeral monuments alike, in his fountains with naked Neptunes stepping out of shells or his elephants carrying obelisks ....

The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, Cornaro Chapel, Santa María della Vittoria Church, Rome

And finally, in the Piazza Navona, still as it ever was today, is the palatial home where Cardinal Giambattista Pamphili was living in 1644 when he was elected Pope Innocent X. There was much commentary at the time about his wish not to move into the Vatican, a remote place on the opposite banks of the Tiber that horrified him with its identikit salons and sacred museums. He wanted to stay here in Rome proper, in this square that had welcomed carriages and horses and the whole Roman spectacle for 16 centuries. The Piazza Navona rose out of the Circus Agonalis, Domitian's stadium built in AD 85 and changed name from Agone, to Navone and eventually Navona. Innocent X decided to advance the prestige of his already powerful family by enlarging their palace and revamping the square. After many a trial, tribulation and false start, Bernini was chosen and began his modelling of the Fountain Of The Four Rivers. Often, when strolling through this piazza by night, one might imagine the Innocent X of Velazquez's portrait, with his critical, calculating eyes looking down from a high window, at the end of the long gallery frescoed by Pietro da Cortona and which, at night, even today, remains lit, as if forcing us to remember him. From here, the pope would supervise Bernini, watching as his work took shape ~ the palm tree bent double by the wind, the Statue of the Moor wrestling with a dolphin, the rock that a stubborn Bernini wanted removing from the ground in order to then somehow drill into it and, as if by magic, make it anchor an obelisk in place. There also, in this night of reminiscences, are Francis Bacon's 40 plus versions of Velazquez's portrait and the video in which Jeremy Iron's inimitable voice reads the Irish-born artist's words: "I feel hungry for life and that hunger has enabled me to live. I eat, I drink ... until the emotion of creation surges. I believe art is an obsession for living."

Dialogue in a Vatican room

It is also said that “Art follows money” so questions about patrons and power are bound to come up. What is happening today in the realms of the art market? Perhaps even asking would be like putting one's foot in the serpentine hair of Bernini's Medusa. While waiting to enter the Vatican Museums, we remember Damien Hirst's 2017 behemoth of an exhibition in Venice that threatened to raise the roof of the Grassi Palace, home of the Pinault Collections. It all left one a little cold. Today, however, Laocoon and His Sons awaits, as do works by Michelangelo and Raphael ... and a room in which we will be mesmerised by Caravaggio's Deposition of Christ, that vertical painting descending from the crown of Mary Magdalen's head in a straight line direct to Jesus' lifeless hand. Under the cornerstone of the tomb there is only darkness and abyss.

A Bernini angel in front of Caravaggio's Deposition of Christ, Vatican Museum, Rome

What is a Masterpiece? wondered Kenneth Clark in his barely 40-page booklet of lecture transcriptions. The answer? It is art that, having entered the mind of a genius in a moment of enlightenment, is capable of giving us either or both butterflies and a punch to the stomach. Caravaggio, from his space on the wall, establishes a dialogue with the Bernini angel in the middle of the room. A kneeling angel, it was once the mold for a Vatican alterpiece and the iron rods that form his wings are exposed to view, having lost the plaster that used to cover them. Likewise, the tightly-packed bundles of straw that shaped his arms under a layer of clay. He is one angel prefiguring another. And a butterfly punch to the stomach.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Bernini's Rome: For Love Of The Eternal City - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

In 2004, 50 years after Frida Kahlo's death (Mexico 1907-1954), thousands of her personal belongings and artefacts saw the light of day again. Photographs, diaries, drawings, books ... along with pillboxes of her painkillers, orthopaedic corsets, hospital gowns, half-used nail varnishes, combs, a bottle of Shalimar - the perfume she wore to try and camouflage "[her] body's smell of dead dog" - clothes, a Revlon eyebrow pencil and pink silk ribbons for her braided up-do hairstyle. Today, all of these dresses and objects, as if characters in her own life story, have left their home (The Blue House in Coyoacan) for the first time ever, en route to the Victoria & Albert Museum in London for the exhibition Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

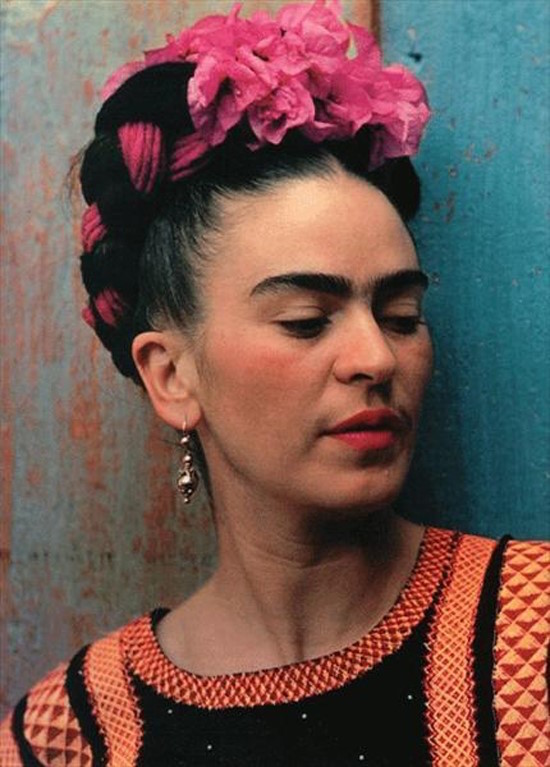

In 2004, 50 years after Frida Kahlo's death (Mexico 1907-1954), thousands of her personal belongings and artefacts saw the light of day again. Photographs, diaries, drawings, books ... along with pillboxes of her painkillers, orthopaedic corsets, hospital gowns, half-used nail varnishes, combs, a bottle of Shalimar - the perfume she wore to try and camouflage "[her] body's smell of dead dog" - clothes, a Revlon eyebrow pencil and pink silk ribbons for her braided up-do hairstyle. Today, all of these dresses and objects, as if characters in her own life story, have left their home (The Blue House in Coyoacan) for the first time ever, en route to the Victoria & Albert Museum in London for the exhibition Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up.

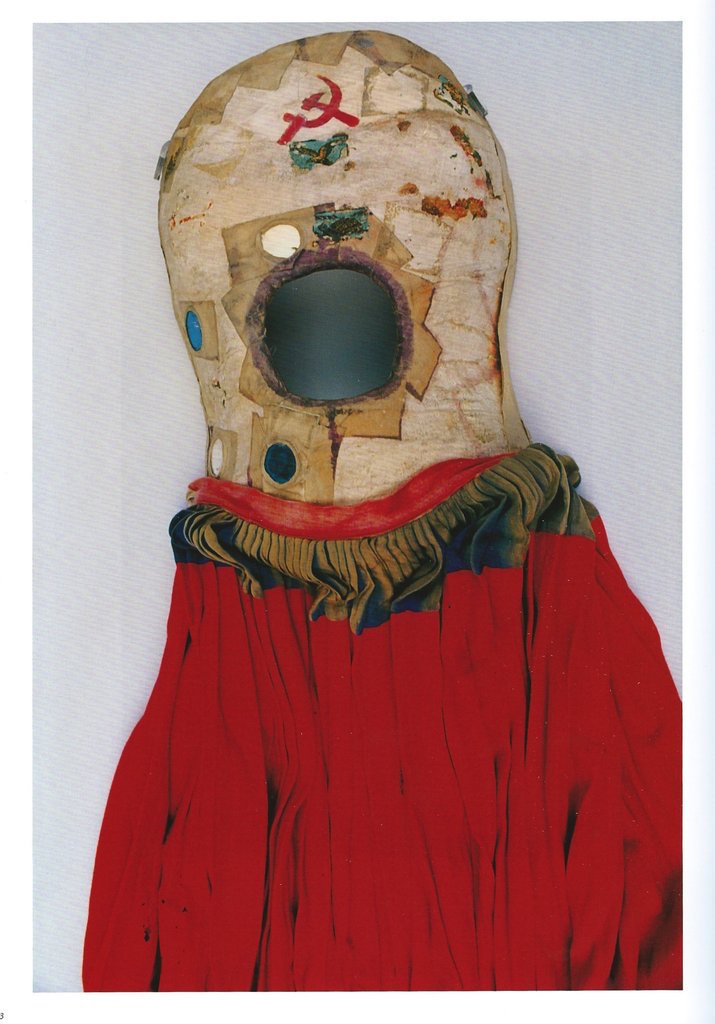

Corset and skirt from Frida Khalo's collection. Photograph from Frida by Ishiuchi (RM Editorial)

It's a story straight out of a Fake News headline. On Frida's death, the painter Diego Rivera, in an attempt to preserve their intimacy as a couple, ordered two rooms in their Blue House home to be sealed with all of possessions and documents locked inside. The moment the little ensuite bathroom adjoining her studio was re-opened and its contents revealed, so too was the message that Frida was transmitting through her clothes. Both Frida and Diego were intense characters, poetically terrible at times and touchingly tender at others. On the centenary of her birth, the press announced the emergence of some 22,105 documents, 5,387 photographs, 168 outfits, 11 corsets, 212 drawings by Diego, 102 by Frida, 3,874 magazines or publications and 2,170 books. These can be found in various compilations, for instance, Frida: Her Photographs and Frida by Ishiuchi (both RM Editorial).

Frida Kahlo's make-up. Photograph from Frida by Ishiuchi (RM Editorial)

The discord in Kahlo's body began when she was just six years old with a bout of polio which left her bed-bound for nine months. Doctors, pain and sedatives made their first appearance in her life. When she recovered, she did so with one atrophied leg and a complex born of being nicknamed "peg-leg" by the neighbourhood children. She, however, enjoyed climbing trees and learned to overcome somewhat but one of her legs remained shorter and thinner than the other. She disguised this by layering pair after pair of thick socks and wearing knee-high boots. From this tender age, she was already beginning to speak through her clothing.

Frida Kahlo's boots. Photograph from Frida by Ishiuchi (RM Editorial)

17th of September 1925: the accident

Frida was 18 that morning she left home with her school books and her boyfriend. “I got on the bus with Alejandro and sat next to the rail with him beside me. A few moments later, the bus crashed into a tram. It was a strange bang, dull rather than violent. The impact sent us flying forward and the rail pierced my body as a sword pierces a bull. A gentleman, seeing my wound bleeding profusely, laid me on a billiard table."

Alejandro described his vision of the incident as: "Frida was left completely naked. Her clothes had been ripped off in the accident. A passenger, no doubt a painter by trade, had got on the bus with a packet of gold-coloured powder. The packet split in half and the gold dust went swirling around her bleeding body." Frida lay there covered with a dew-like sprinkling of gold. The diagnosis: triple fracture to her spinal column, fractured collarbone, fractured third and fourth ribs, dislocated left shoulder, thigh fractured in three places, perforated stomach and vagina, eleven fractures to her right leg, dislocated right foot. The medics of the Red Cross gathered up the pieces of her body under no illusions that she would survive the operating table. Her human capacity to withstand such horrific pain would have seemed impossible to them. As would her indomitable will to live.

On leaving the hospital, her mother settled her in a four-poster bed with a mirror attached above and ordered a custom-made easel. Frida remained locked inside her own world, focused on a mirror the size of a picture portrait. During the day, she read avidly between visits from her schoolmates. Chinese poetry by Li Po, Bergson, Proust, Zola and also articles about the Russian revolution and stamp books by Cranach, Durero, Botticelli and Bronzino. But as night fell, so did the images that devoured her, isolated her and terrified her. “Death dances around me all night long", she wrote to Alejandro.

Diego Rivera recalls how Frida first made her appearance in his life: “One day, I was working on frescos at the Ministry Of Education when I heard a young woman's voice shouting up at me saying, Diego, please come down from there. There's something important I have to talk to you about ... and standing below me was a girl of about 18, nice figure, a bit agitated. She was wearing her hair down and she had these thick, dark eyebrows that met in the middle. They looked like the wings of a blackbird." Rivera ~ then 42, nearly 6 foot tall, 16 stone, already married to Lupe Marín and one of the "Three Great" Mexican muralists of that time ~ accepted the role of Frida's boyfriend. Her family commented that it was "the union of an elephant and a dove".

Diego was her God, her father, her son, her "second accident". Every morning, as if in a ritual, Frida would dress herself up like an idol, designing her costume and jewellery so as to hide the wounds on her body. She adorned herself for him as the women of Tehuana did, seeing in their indigenous clothing a political statement and a vindication of her Mexican heritage. Those outfits comprised 3 pieces: the petticoat, the Huilpil (a square-cut blouse that made her look taller) and her updo of braids and flowers which drew the onlooker's gaze upwards to her head and upper torso and away from the lower part of her body.

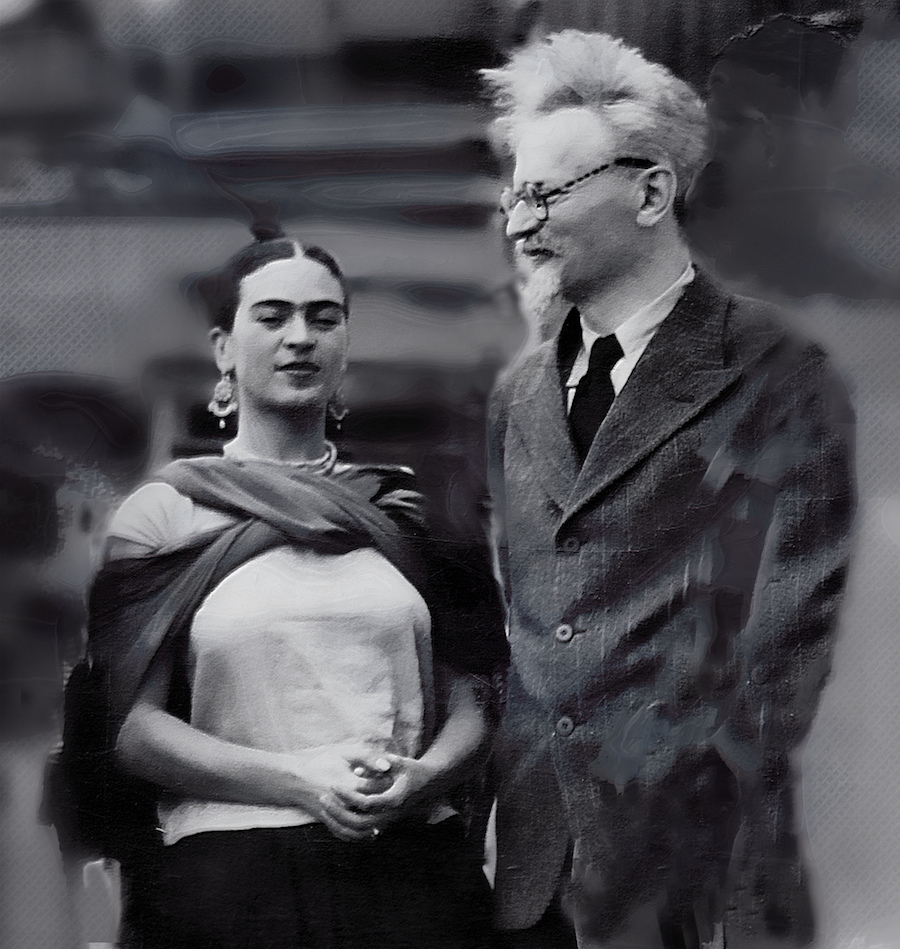

Frida Kahlo with Diego Rivera

The Blue House

The building that today houses the Frida Kahlo Museum was built by her father 3 years before she was born and painted a bright cobalt blue to ward off evil spirits. It was then extended by Diego and decorated by Frida to resemble a microcosm of tropical vegetation with cacti, orange trees and Aztec idols perched on a small pyramid where a coterie of animals held court, all humanised by their names.

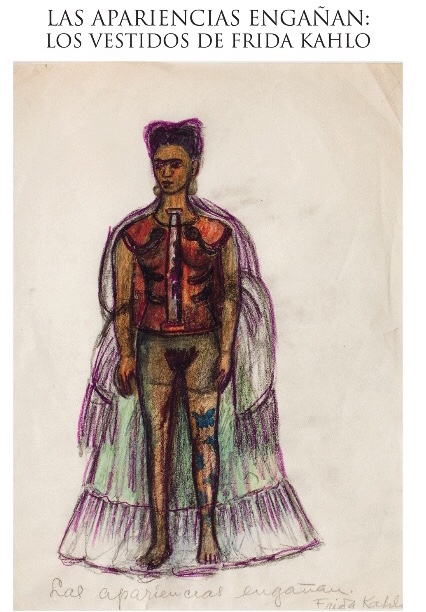

In 2004, one of the most exciting moments at the opening of the sealed rooms was the discovery of a drawing entitled "Appearances can be deceiving". In it, Frida's broken, naked body appears as if X-rayed, with blue butterflies painted over her leg fractures and a slender pillar in place of her spine. She then, in purple pencil, drew a sheer gown over herself leaving her battle-scarred body visible. It is curious in that Kahlo, who would dress in real life with a view to disguising her disabilities, allowed those very disabilities to be viewed under stark scrutiny in this and other paintings.

Poster for the exhibition based on Frida Kahlo's drawing "Appearances can be deceiving", Coyoacan, 2013

In 1937, Leon Trotsky moves into the Blue House and stays there for two years, making it his revolutionary fortress. It didn't take long for the author of The Permanent Revolution to succumb to the charms of his beautiful hostess. They would speak to each other in English, a language Trotsky's wife Natalia couldn't understand, and Frida would pass him love notes she had hidden in her clothes.

Frida Kahlo with Leon Trotsky

Pablo Picasso, too, would adorn Frida. On a visit to Paris, he gifted her a pair of earrings shaped like hands that dangled and twinkled below her braided hair of bougainvillaea and bows. She was forcing us to look at her face. Her lips, painted bright red, always appeared tightly closed in photographs and paintings alike. She never showed her teeth, hiding the invisible jewels that were her gold incisors and which, for special occasions, she would set with little pink diamonds.

Frida Kahlo wearing the earrings Picasso made for her

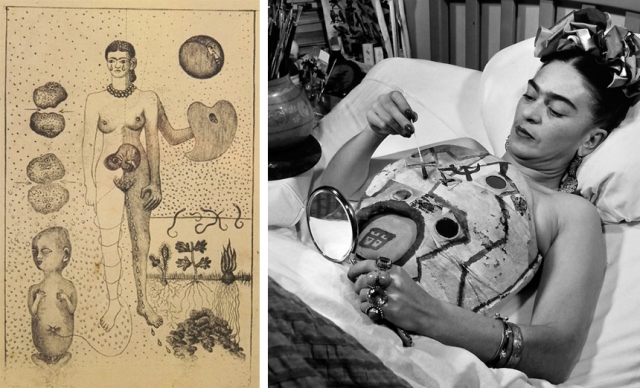

Frida Kahlo painting her corsets

“I am disintegration”

In early 1950, Frida was admitted as an in-patient for a year in Mexico City. Diego moved into the room next to hers and the hospital stay became a party: "I always kept my spirits up. I spent a lot of time painting because they kept me dosed up on Demerol. That substance made me happy."

A year before her death, the gallery owner Lola Alvarez Bravo organised an exhibition. It's now April 1953. Diego arranged the transfer of her 4-poster bed into the middle of the space. Frida made her triumphal entrance accompanied by the wail of ambulance sirens. The guests gathered around her as she persevered with the aid of painkillers. She was the embodiment of triumph over pain. Then after this homage came the verdict on her right leg. It would have to be amputated. Frida wrote in her diary: "I am disintegration."

From then on, Frida devoted herself and her time to fine-tuning the new parts of her broken body. Her red boots, the finishing touch to her false leg, she decorated with Chinese embroidery, gold thread and little bells. These are, without doubt, the most enigmatic of all the objects in this exhibition. As are the corsets she had to wear, a stark reminder of her torture. Her relationship with them was one not just of necessity and support but also of rebellion. From then on, we would only ever again see Frida approaching in her wheelchair, preceded by the murmuring jangle of her jewellery.

Meanwhile, death was inching nearer, on tiptoes. She dressed, now, for days and nights in bed painting and this was how she prepared for her departure from life to heaven. She realised she was killing herself. The drugs and alcohol that gave her relief and release were likewise a death sentence. At the age of 47, Frida is cremated. It is said that, on the exit of her remains from the crematorium, Diego swallowed a handful of her ashes.

Frida Kahlo's orthopaedic boot. Photograph from Frida by Ishiuchi (RM Editorial)

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up

Victoria and Albert Museum

Cromwell Road, London

Curators: Claire Wilcox and Circe Henestrosa

From 16 June until 4 November 2018

(Translated for the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca

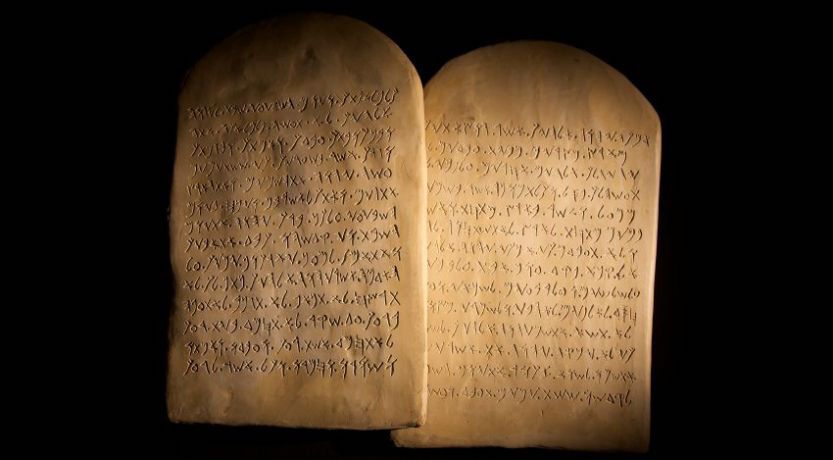

Both among those who, by reason of their religion and culture, consider themselves to be Jews and for those living as Jews whilst also considering themselves an integral part of the secular and cosmoplitan mindset prevalent today, the question of a Jewish identity and the main issues involved in defining it is a recurrent one: for instance, the Jewish take on history and time, Jewish persepectives as regards individuality and collectivity, and, of course, anti-Semitism to name but a few. With the sole aim of contributing to the dialogue this type of reflection invites, I would dare to posit the two-way character, at once ambiguous and conflictual, of the Jewish estate that this conversation, broadly speaking, might well end up concluding.

|

Contributor: Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca, |

|

Both among those who, by reason of their religion and culture, consider themselves to be Jews and for those living as Jews whilst also considering themselves an integral part of the secular and cosmoplitan mindset prevalent today, the question of a Jewish identity and the main issues involved in defining it is a recurrent one: for instance, the Jewish take on history and time, Jewish persepectives as regards individuality and collectivity, and, of course, anti-Semitism to name but a few. With the sole aim of contributing to the dialogue this type of reflection invites, I would dare to posit the two-way character, at once ambiguous and conflictual, of the Jewish estate that this conversation, broadly speaking, might well end up concluding.

I am referring, in particular, to that indeterminate oscillation, as yet unresolved but still so characteristic of the Jewish people, between the temptations of sectarianism and the impulse to participate in the dynamics of society on equal terms with the rest of its members. This seeming duplicity, this conflict or ambiguity in their position would be incomprehensible were we not to take into account the tenets of Judaism as a religion and the vicissitudes of concrete Jewish history up to the present. It will be a lay understanding of the specificity of religious tendencies and the mystical orientations of Judaism - which rewrite Judaistic history from a deep understanding of the reciprocal influences of religious, social and political factors - which can, to a large extent, shed light on the problems surrounding the situation of Jews in today's world.

Gershom Scholem, one of the greatest scholars of Abrahamic spirituality, pointed to messianism and redemption at the core of earliest Jewish belief as its defining elements, albeit as undertood very differently to the Christian view of them. Christianity sees redemption as an event that happens within the spiritual domain, invisible, inside the soul, in an individual's personal universe and one that refers, essentially, to an inner transformation that doesn't necessarily change the course of history, while for Judaism, the coming of the Messiah and the ultimate redemption are, essentially, an historic event that must needs take place both in the public arena and within the bosom of Jewish society. In other words, it is a visible, temporal happening that would be inconceivable without that outward manifestation. An internalised redemption interpretation has always seemed to Judaism a get-out clause, a loophole, an escape from the scrutiny and challenge that Messianism represents in terms of actively hoping for and, therefore, contributing to the restoration of creation to its original perfection.

But this state of active hoping and waiting is often at odds with a centuries-long evolution that spans everything from an optimism that fomented even large-scale socio-political revolutionary movements to an attitude of disillusionment - in no small measure determined by the failure of those very movements - in the midst of which the merely spiritual tends to prevail over the need for social and political action. It is at this moment that "the Hebraic political body stops functioning and its people withdraw from public life and history".

Scholem himself recognised, in this deep disillusionment with messianic hope, one of the major causes of the Jewish community's retreat inside itself, of its tendency to cloister and isolate and limit itself to just the conservation of its threatened identity and, perforce, of its political dismemberment. It is this situation that makes the Jew - and not just in the metaphysical sense of the clichéd "Wandering Jew" - a true symbol of the condition of every modern man and woman, as an individual deprived of community bonds, oblivious to true solidarity and dispossessed of a common homeland, as explained a few years ago by the French scholar and philosopher André Neher. According to Neher, the Jew is a voluntarily disenfranchised pariah who does not consent to being subjected to the worldly conventions that constitute a collective identity, but rather accepts their condition of marginality and becomes a conscientious pariah, even though this means renouncing the advantages of social success.

It is, perhaps, from this point of view of social marginalisation that one might best understand the Jewish approach to history, their exodus, their wandering, displacement and diasphora over the centuries. Judaism, according to Franz Rosenzweig, in so far as it positions itself outside both the course of history and the modern concept of history, imposes itself as the voice advocating the notion of itself as the measure and judge of all things. This does not mean to say that, in order to judge history, one has to be Jewish. However, it is the Jewish people who have demonstrated how it is possible to liberate not only themselves but Gentiles also from the weight of history, in as much as they do not wish to be part of it but, rather, to look at it in its entirety from the outside.

But if social marginalisation can result in an aptitude for historical critique, it can likewise induce behavioural patterns dominated by a desire to distinguish itself or to display qualities that speak to a, supposed or actual, Jewish superiority. This is what led figures such as Benjamin Disraeli to claim it a strategic virtuosity or an almost occult power over non-Jewish society which, both effectively and lamentably, served in its day to reinforce an anti-Jewish sentiment and anti-semitic prejudice. Instead of an objective judgement on the difference between Jew and Gentile, this attitude paved the way for simplistic, mytho-religious counterpositions and a manichaeism of good and evil. According to Hannah Arendt's detailed analysis of the social situation of Jews in pre-Nazi Europe in the first section of her The Origins Of Totalitarianism, it is the apoliticalism of Hebrew communities, together with the depoliticisation of the bourgeois masses, that contributed most to the rise of anti-semitism. Following on from Scholem, Arendt explains this illusory pretension to superiority felt by some emancipated Jews as one of the consequences of the bankruptcy of Messianic hopes and the Jewish secularisation that ensued. Judaism, once its spiritual and religious essence is diluted down, tends to transform itself into the mere fact of ethnic and linguistic belonging. Too "enlightened" to show any religious convictions, the emancipated Jew maintains, nonetheless, their links to the claim of belonging to the "chosen people" which places them outside both Jewish society proper and that of the Gentiles. The condition of this European Jew, within the vanishing framework of a bourgeoisie increasingly distant from its revolutionary origins, becomes almost elusive.

One way or another, the Jewish condition then takes on the aspect of a worldlessness or uprootedness. Lost in the secularised dream of heaven on earth, European Jews allow their political history to depend on external, casual and even sinister factors. And so ... does this not come to confirm the failure of the notion of politics not just in the Jewish world but in the modern world in general? Social particularism, obsession with prestige and the dissociation between citizenry and institutions are taken-as-read characteristics of contemporary Western society. However, all things considered, something positive has also come out of this failure, namely, that the distinction between a community's religious and political practices be built on the defence of a necessary distinction between the private and public spheres. Cultural traditions, ethnic and linguistic belonging or religious faith are what constitute the uniqueness of the actors on the world stage. But the chance for each of them to act freely in this world common to us all, whilst maintaining their differences from it, require an ability to transcend their unicity and singularity.

That is why a nation state like Israel, founded after the Holocaust in order for Jews to have their own political space, may seem regressive in the light of these modern world achievements and to the extent that it is based on strong confessional connotations. Perhaps the right direction to go in is not that of a search for a strictly nationalistic solution but rather, conversely, one that attempts to reconcile the specifically Jewish situation with that of society as a whole, one that tries to unite Jewish aspirations to emancipation with the right of all peoples to self-determination. In order for Jews to be liberated form their status as excluded and persecuted, it is necessary that they be themselves, in any public sphere, and that they be equal to non-Jews, assuming and themselves demanding equality with all others. They will, of course, still need to maintain their own historical, religious and cultural identity. As Emmanuel Levinas rightly observed, Judaism is the face of an exteriority that cannot be engulfed in an undifferentiated entirety. But they must also transcend this identity and move towards a structure of universal relations. Only by acting independently of their ethnic origin or religious faith can Jews acquire the right of access to that common public domain in which the status of plurality becomes reality, or, in other words, where they can live as distinct and unique beings among their equals.

In a nutshell, the Jewish condition, having now become a symbol of modern exile and rootlessness, would then assume the fundamental significance of a struggle for the conquest not just of a physical or a social space but, more importantly, of a political one. A space where the irreductable, entrenched differences between people based on their origins no longer constitute a factor in discrimination but become, rather, the foundation for the equal and pluralistic participation of all in the practice of politics.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- But just who are the Jewish people? - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

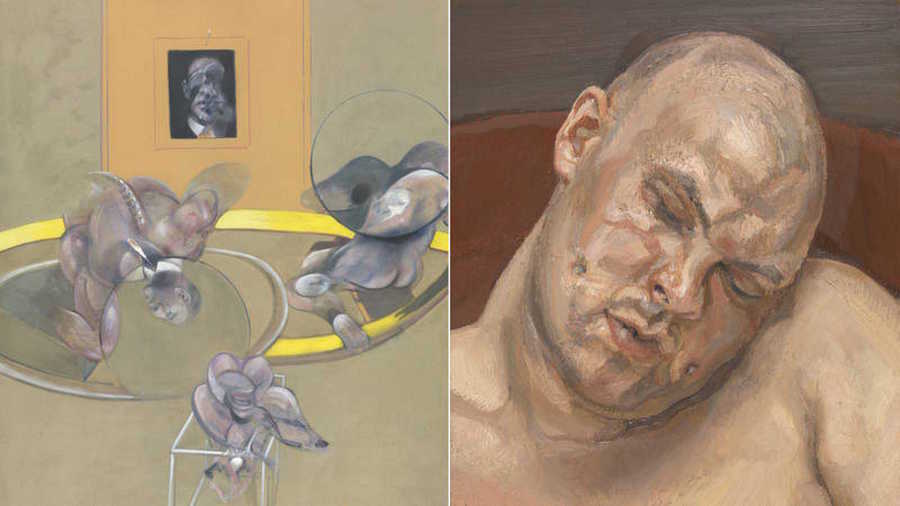

It might seem these days that even the Thames is struggling to keep to its course given the exhibition currently making waves at the Tate Britain sitting on its banks. It tells the story of British art before and after Francis Bacon (1909-1992) and Lucian Freud (1922-2011), welling up from a hot spring of works by Stanley Spencer, Chaïm Soutine, David Bomberg, Walter Sickert and Giacometti, settling in the delta of thirty or so paintings by the eponymous rivals and ending with a small retrospective of contemporary painters such as Slade graduate Paula Rego and Jenny Saville. All too human: Bacon, Freud and a century of painting life is the title borrowed from Nietzche's book by Tate Britain for its exhibit bringing together 20th and 21st century British artists who sought a new way of capturing the physical and psychological essence of human beings through the medium of paint.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

Francis Bacon Three Figures and Portrait, (1975) and Lucian Freud, Leigh Bowery (1991)

It might seem these days that even the Thames is struggling to keep to its course given the exhibition currently making waves at the Tate Britain sitting on its banks. It tells the story of British art before and after Francis Bacon (1909-1992) and Lucian Freud (1922-2011), welling up from a hot spring of works by Stanley Spencer, Chaïm Soutine, David Bomberg, Walter Sickert and Giacometti, settling in the delta of thirty or so paintings by the eponymous rivals and ending with a small retrospective of contemporary painters such as Slade graduate Paula Rego and Jenny Saville.

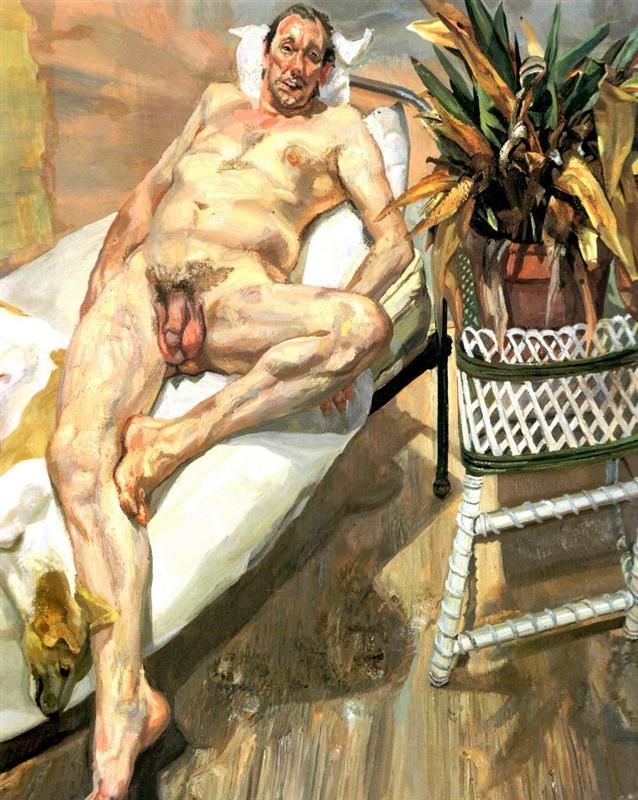

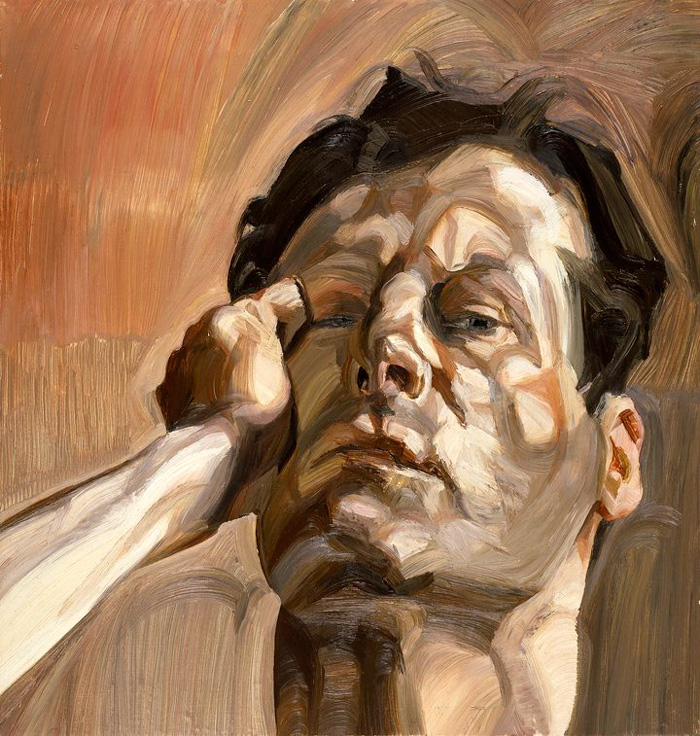

All too human: Bacon, Freud and a century of painting life is the title borrowed from Nietzche's book by Tate Britain for its exhibit bringing together 20th and 21st century British artists who sought a new way of capturing the physical and psychological essence of human beings through the medium of paint. After WWII, British painters made one of their greatest contributions to the art world by reinventing the European tradition of figurative painting. By 1950, Michael Andrews, Frank Auerbach, Freud, R.B. Kitaj, Leon Kosso and Bacon were banded together under the label "London School" at a time in the lives of this group of artists and friends when they all pledged allegiance to past artistic traditions and orthodoxy whilst sharing a rejection of the abstract.

But, how does one paint life? Is it possible to capture the human experience on canvas? These were the questions that concerned and fascinated the artists showcased here with Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, trapped in their world of solitude and torment, as the centrepiece.

Jenny Saville, Reverse (2002-2003)

Two Lucian Freuds?

Until the 1960's, Freud appeared to be painting with a magnifying glass. In an anteroom, separate from the main gallery dedicated to his later work, is Girl with a White Dog (1950). Kitty Garman, his then wife, is depicted sitting with a dog leaning on her legs, her naked body wrapped in a yellow bathrobe left deliberately open to reveal her right breast, the left one covered and her hand cradling it as if feeling for a heartbeat. The detail with which Freud studies the various surfaces is reminiscent of the Flemish Primitives. Kitty's thick, wavy hair as compared to the dog's rough coat, from the fluffy pile of the towelling dressing gown to the tassles that braid its belt. Those were the years of Freud's fascination with Ingres so Kitty's gleaming gold wedding band could even be deemed a dedication to the French Neoclassisist.

Freud had always had an obsession with painting eyes. They seemed to him to be the source of presence and power. They could, and even moreso their movements, express everything from desire to hatred, trust to mistrust and whether they decide to look us back in the eye or not. Pupils and the enigma of their dilation on observing an object of interest or fear intrigued him. Kitty's sad eyes are like two pools full of glints and contained tears. The dog's eyes, however, are the ones that, as if a mirror in a van Eyck painting, reflect the window in Freud's studio.

Lucian Freud, Girl with a White Dog (1950)

Towards the end of the 50's, Freud left drawing behind to focus on painting. He changed paintbrushes, replacing the fine, marten-hair ones with thicker, boar-bristle ones that facilitated his evolution towards those denser and more expressive brushstrokes characteristic of the later stages of his painting and displayed in the next room. There, man and beast return to centre stage in the form of David and Eli (2003-2004), his assistant and his dog exposed on a narrow bed. It is a striking nude study of epic, no-holds-barred proportions. The model in all his rawness, nothing more. It's as if Freud had invented a brand new style of nude and shone a violently bright light on it, subjecting that mysterious layer that is human skin to merciless analysis. Its thickness, its flaccidity and the inherently matte colours of pale skin, inseparable from a painfully lived reality.

Lucian Freud, David and Eli (2003-2004)

Bacon and Freud: not a marriage made in heaven

In his book Man In The Blue Scarf, in which he relates his conversations with Freud while having his portrait painted, Martin Gayford recounts how, one day between poses, they were looking through a book on Van Gogh. Freud chose an Arles landscape saying: "Many people would say this is inspired by Japanese art but I would much rather this one than all Japanese landscapes of the 19th century put together. The most difficult thing is being able to draw well" and, mentioning Bacon: “Francis scribbled away constantly. His best work came solely from his own inspiration, I mean, when it wasn't based on drawing well."

Despite their differences, Bacon and Freud will be together forever in the minds of art historians. Gayford explains that the same thing happens with British artists as with the proverbial London bus delays ~ you wait for hours with no sign of one and then two arrive at the same time. In the 1880's, J.M.W. Turner and John Constable were seen as a pair and then there was nobody else until Bacon and Freud after the Second World War. Like Turner and Constable, Bacon and Freud made a bad marriage of artists, with as much dividing them as uniting them.

Francis Bacon, Study after Velázquez (1950)

Bacon, for his part, was obsessed with painting mouths: terrifying jaws at the end of eel-like necks that suck and swallow nightmares, lovers, pain, boardgames, alcohol, war and screams. It's life as a taut twine between birth, skinned flesh, violence, the great and the deep in human feeling and, ultimately, death. And, simultaneously, the most breathtaking beauty based on his innate taste for the serene monumentality of the Old Masters such as Rembrandt, Velázquez and Goya. But it was Picasso who really kickstarted his career, as did the literature of writers from Aeschylus to T.S. Eliot. This whole palimpsest comprising layer upon layer of Venetian colours, the oranges and pinks absorbed by black he daubed on the walls of his studio, transforming it into a giant 3-D palette, is what enabled him to do something that was only possible after the first Freudian generation ~ to paint trauma.

Rarely did he paint life models, prefering instead to work from photographs and movie stills. His painting came straight from his own imagination, capitalizing on every thought that entered his head "as if they were transparencies". He rejected the image as imitation. For him, it was all about that instantaneous piece of evidence transmitted directly to the brain and without the need for verbal intervention or "what happens in that instant to the nervous system". From there ,and not needing the logic of resemblance, his work would take off from his own aesthetic vision and from the beauty and energy of the strokes that, for him, represented a struggle and an intimate relationship between a painting and its painter.

Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait of Lucian Freud (1964)

Standing in front of Bacon's Study after Velázquez (1950), we are reminded of this Irish-born artist's love of the Prado Museum in Madrid. His frequent visits from 1956 onwards are described by Manuela Mena as his eyes devouring the paintings of Velázquez: “He would study the brushstrokes, which is where it's all at, right up close and with deep concentration". He would go from painting to painting, "observing his subject much like someone examining the skin of their lover." The Prado exhibited Bacon in 2009 which, in its way, forever united him with Spanish painting of the 17th century.

Lucian Freud, detail from Man's Head (Self Portrait 1), (1963)

Finally, the heat in this boxing ring of Tate Britain's creation rises as we approach the face-off between two canvases. In the red corner, Bacon's Study for a Portrait of Lucian Freud (1964), a painting unseen by the public since 1965, and in the blue corner, Freud's self-portrait Man's Head (1963). Freud painted Bacon twice. Bacon painted Freud over 40 times.

Francis Bacon (left) and Lucian Freud photographed by Harry Diamond, 1974

All too human: Bacon, Freud and a century of painting life

Tate Britain

Millbank, London

Curators: Elena Crippa and Laura Castagnini

Until 27 August 2018

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Bacon versus Freud, a battle history - - Alejandra de Argos -