|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

This little journey begins on a wall. As dusk falls, so begins a dialogue between that wall and a window, a transparent, vertical frame that reflects in the Swiss meadows outside and surrounding the Beyeler Foundation, all fresh, serene, rose-tinted; set against the electrical charge of a horizontal canvas turned into a muted scream depicting the Wailing Wall. It’s Ernst Beyeler and Renzo Piano in the company of Marlene Dumas. One of those rare moments for meditation: architecture resting its hand on the small of the painting’s back to guide it through a perfectly synchronised, beautifully choreographed dance.

Ernst Beyeler was one of the greatest ever art dealers, In 1970, along with Trudl Bruckner and Balz Hilt, he created the Art Basel fair. He and his wife Hildy aquired a world-class collection of masterpieces and commissioned the architect Renzo Piano to design an exquisitely beautiful museum in which to house them. It opened in 1997 not only to exhibit the Beyeler’s own private collection but also to showcase the world's most important contemporary art exhibitions.

Until 6th September 2015, the Beyeler Foundation museum was the venue for Marlene Dumas’ The Image As Burden, a retrospective of 40 years worth of work comprising over a hundred pieces.

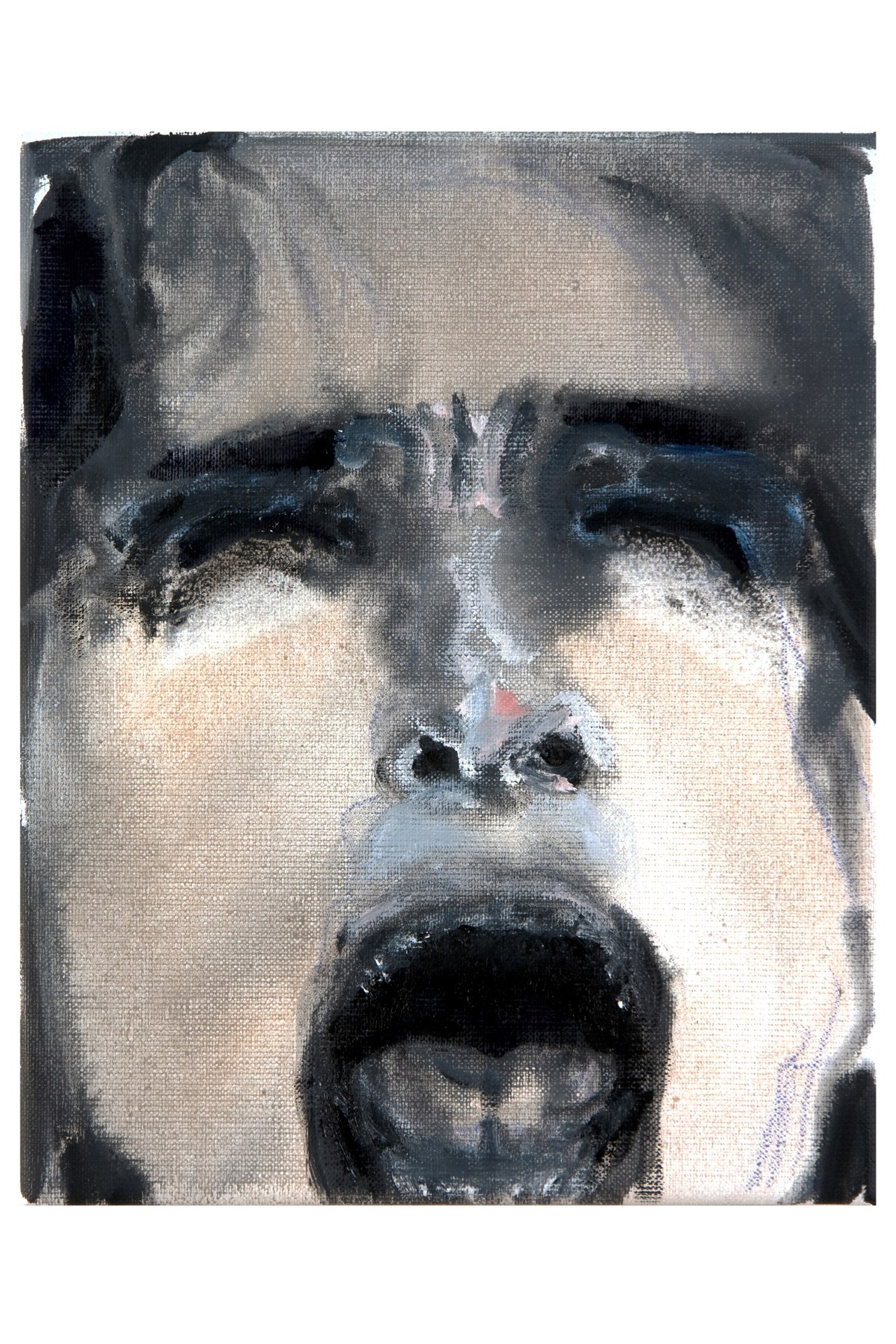

Broken White, 2006.

The Burden of Apartheid

Marlene Dumas (Cape Town, 1953) is an artist who sails deep through the swell of waves and dense, eclectic backdrop that is her work, and very much at odds with her physical appearance it is, too. She is slight of build, bubbly, with playfully expressive pale blue eyes, a booming laugh and a fresh-seeming joie de vivre

But behind that facade, Dumas is a tireless worker and avid collector of postcards since early childhood and still, even today, in her untidily tidy Amsterdam studio, she has everything filed, ordered and catalogued. Dumas, whose figurative style centres the human face and the human body, never works from a live model. She invariably works from a flat, printed, two-dimentional image. Her sources are the hundreds of thousands of photographs cut from newspapers, magazines, some of them pornographic, books on the mentally ill, the “lunatics”: a word she says she likes because of its association with the moon’s influence on our states of mind, catwalk models, “I cannot conceive of a trip without Time magazine”, pamphlets, art postcards and, most of all, her own polaroids. “One could say that South Africa is my content and Holland my form. And I think, as well, that the images I use are universal, known to everyone. I deal in second-hand images and first-hand experiences. My models have already been moulded and posed previously by somebody else. There are no virgins here.” she insists.

Mamá Roma, 2012.

Dumas paints from a place of condensed reality. Hers is painting that questions. Or targets with the precision of a dart. Expression, mystery, the connection between public and private, dreams and reality. Take that portrait in blue of Amy Winehouse. Isolated figures, usually with no background, abandoned in the solitude of a canvas and its sadness.

Dumas is fully aware of the power of the photography and films she has been addicted to her whole life. It was from celluloid, and the looks to camera of its actors, that she learned the rules of imagination. She knows she must surpass the magic of photography and magnify the power of the filmed image in order to justify painting them. This is the motive behind her characteristic focus: the zoom button here, a close-up there, chopping and cropping into strange dimensions. See her paintings of gigantic babies. “I’ve never had the first clue about the actual size of a head. Anatomy never interested me.” she says.

Amy-Blue, 2011.

Her themes are extreme and recurrent: death in multiple aspects and facets. Paintings such as The Kiss (2003), Lucy, Stern and Alfa (2004) are large canvases of dead, apparently serene, women. They are oil on canvas but have a strange, aqueous, veil-like consistency, as if the contours and the colours of these heads were seen through the filter of a memory, dream or nightmare. Violent deaths: Dead Marilyn (2008) or Dead Girl (2002), the head of a young Palestinian girl falling down lifeless, killed. The death of the Dutch film director Theo van Gogh or a dead swan, its sinewy neck and unfurled wing white against a black background.

The Swan, 2005.

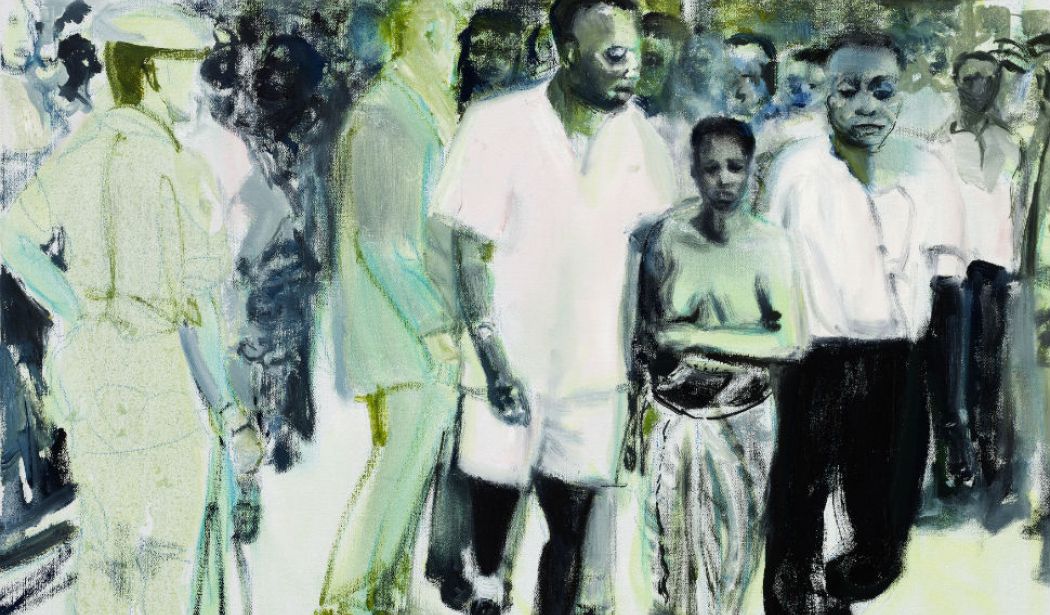

And then there is race, above all else, race: its message, its meaning, Dumas’ use of the colour black. Racism that stretches from Apartheid to the Wailing Wall of Jerusalem. The Wall (2009), The Widow (2013). Dumas inherited from Gerhard Richter an interest in “series” painting and also, by the same token, an interest in hanging pictures in such a way as for them to be grouped together in rooms by theme. She is able to fill whole spaces with hundreds of drawings of little tiny heads in black and white, each one unique and distinguishable if only from its expression. There have been multiple series sets since Models (1994) up to and including her latest and as yet unfinished Great Men (2014).

Models, 1994.

At a time in Madrid when the memory of Zurbarán’s Christ and Van der Weyden’s recent departure are still fresh in our minds, the two series of Crucifictions and the portraits of Christ in Dumas’ The Perfect Lover are akin to questions. Van der Weyden’s St John, desolate at the foot of the cross in the 3 metre high Calvary, was powerful but were there ever any Christs as abandoned to their solitude as Dumas’ Gravitá (2012), or Solo the year before?

Gravitá (detail) 2012.

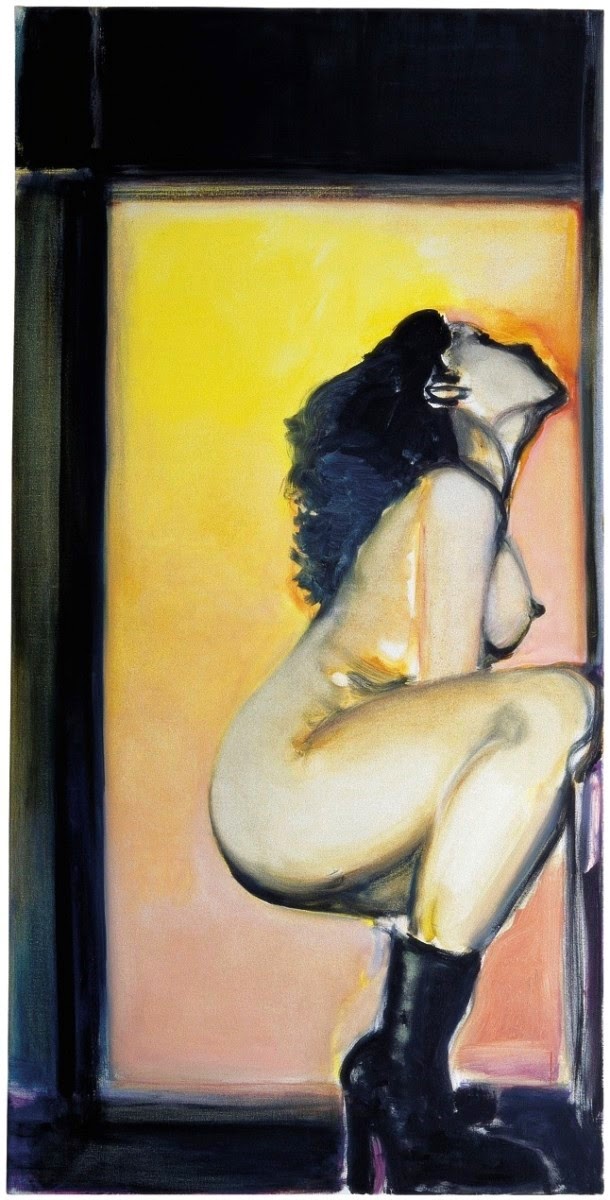

And at the other extreme, her pornography series: strippers, nightlife, neon lights, young men in explicit poses, young girls midway between innocence and abuse, leather boots, black stockings ...

"I paint because I’m a woman” she says. “I’ve always wondered why the great themes of life and love must be conceeded to film directors, authors or pop stars. I want to paint all of that, too.” And her pictures became ever and even more intense. Peter Schjeldahl, in the New Yorker, said that Dumas’ pictures are loaded with such weight that it’s a mystery how they don’t fall from the wall and break the floor.

Leather Boots, 2000.

A farm in Africa

Like Karen Blixen, Marlene Dumas also had a farm in Africa. Of Boer descent, her roots were forged by the essence of rural Afrikaaners: a solid, conservative milieu, strong religious principles but also openness and tolerance. Her childhood in Kuilsrivier (a Cape Town suburb) was a quiet, happy one, with a close-knit extended family of three grandparents and her Dutch mother, a woman wholly devoted to flowers, her three children and her vineyard. Marlene drew in the sand and learned from illustrated books and bibles. She enjoyed open-air cinema on Saturday afternoons. She had two brothers, one a viticulturist and the other a theologian from whom she learnt what it is to have a certain moral maturity and, more importantly, what it means to have a vocation. They were a close family, appearing not to need anything from outside their insular world. In 1976 she won a scholarship to study in Amsterdam where she still lives today: "My homeland is South Africa, my maternal language is Africaans, my surname is French .. I sometimes think I’m not a true artist because my heart is too divided up. My studio is my house. I think I’m like a snail, always carrying its life and homeland on its back.

The Blindfolded Man, 2007.

Marlene Dumas’ studio has no natural light. It’s small, white-walled, cement-floored, spattered by decades of work and paint. Almost everything is on the ground, photographs, brushes on paint pot lids and a small wooden brick she only very occasionally steps on to observe the results of her work. Now 62, Dumas often paints on the floor, on all fours, on a stretch of paper much larger than she is. She paints very fast, spasmodically, like an image captured in an instant on her retina, like water coming into contact with a black paint stain. From here emerge the fine black brush strokes that trace the eyes of a young nude. The water and the paint move around the paper leaving an abstract marking somewhat reminiscent of Bacon, of rivers or of a face reflected in the water at the bottom of a well.

"I’d love my paintings to be like poems. Verse is like naked words that have undressed themselves.” she says. Everything to do with Marlene Dumas aquires a literary density. She writes with her paint and she writes without making books, essays and poetry redundant. She also sometimes writes short phrases in some of her pictures. She likes to write her own exhibit material and press releases as she doesn’t see why or how anyone else should or could define what her art is trying to say. She has always considered herself a descendant of Alexandre Dumas and, for that reason, a “musketeer”, a warrior armed with both pen and paintbrush, too.

The Widow, 2013.

It is also Dumas behind the suggestive titles of her series or exhibiitions: The Eyes of The Night Creatures, Measuring Your Own Grave or her latest, The Image as Burden, yet one more example of the sheer quantity of layers, meanings and nuances in everything Dumas does. This last title comes from one of her small oil paintings of the same name. In it a man, posed Pieta fashion, holds a woman, the image, lifeless, in his arms. He looks at her tenderly and supports the weight of her body with no small effort. Dumas explains that the origin of that pose was a scene from George Cukor’s film, Camille, in which Robert Taylor carries Greta Garbo’s white-clothed body. Dumas’ scene emerges from a black background, two outlined profiles, almost African mask-like, are painted in Dumas’ smudged, discoloured tones, as if with dirty brushes: from black and deep blue to white. Black paint in an old kitchen tin thrown onto the floor of her studio is, perhaps, what Apartheid meant for Dumas.

The Image as Burden, 1993.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Marlene Dumas at the Beyeler Foundation - - Alejandra de Argos -