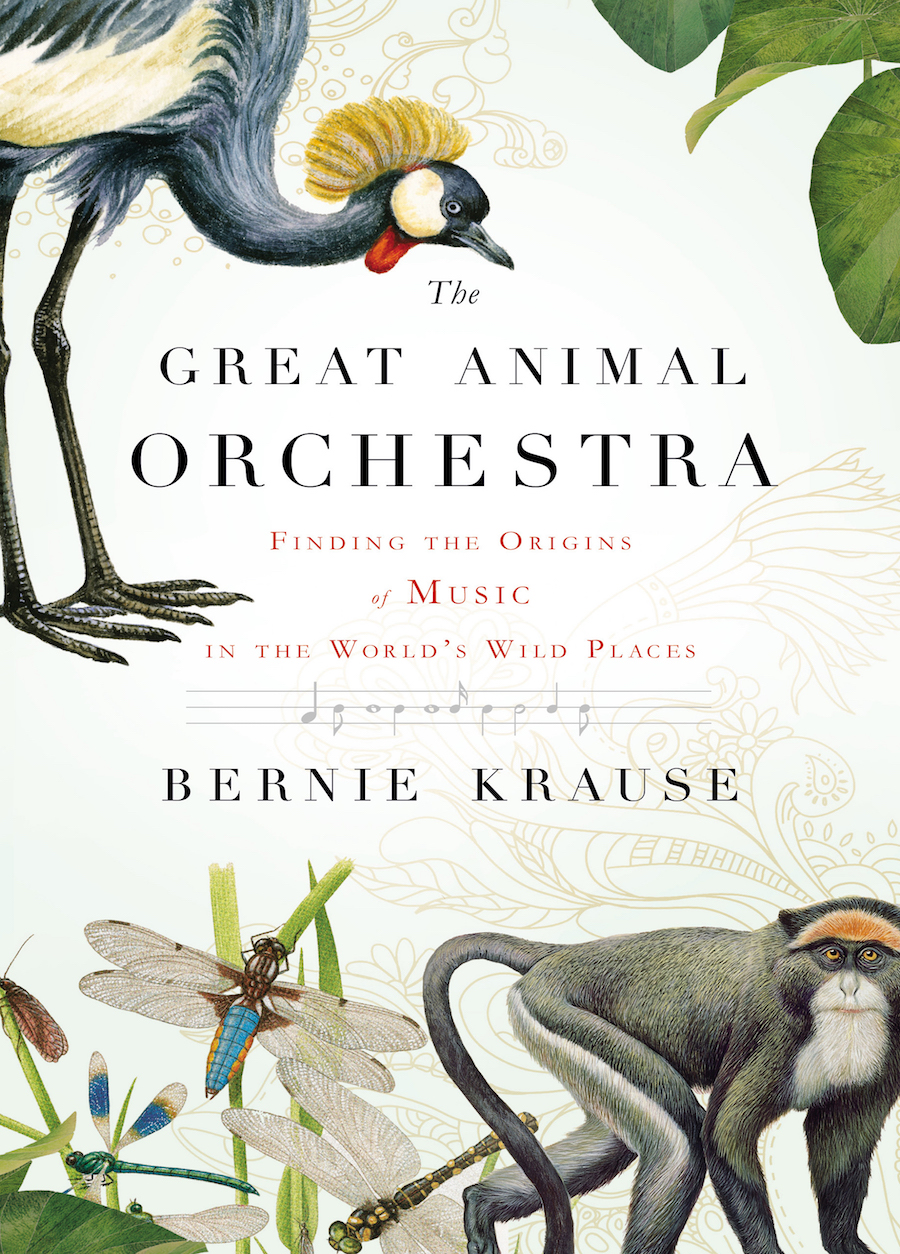

At least that is what the musician, scientist, naturalist and author of the book "The Great Animal Orchestra” (Detroit, Michigan, 1938), Bernie Krause, thinks. He wrote this book to show people that animals taught us to dance and sing and that soundscapes, particularly biophony and geophony, terms coined by the ecologist, have exercised a decisive influence on our culture.mKrause was a member of the famous American folk group The Weavers. When it broke up, he formed the electronic music duo Beaver & Krause. They introduced the synthesizer into pop music in the 1960s, playing in sessions for musicians such as George Harrison, Mick Jagger, Quincy Jones and Barbra Streisand, among others.

Author: Elena Cué

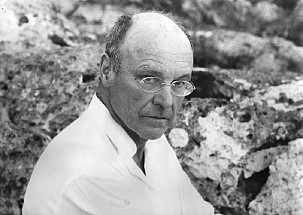

Bernie Krause in St. Vincent’s Island, Florida (2001). By Tim Chapman.

"The truth is the Greek myth got it wrong. It wasn't Orpheus who taught music to the animals, but the reverse". At least that is what the musician, scientist, naturalist and author of the book "The Great Animal Orchestra” (Detroit, Michigan, 1938), Bernie Krause, thinks. He wrote this book to show people that animals taught us to dance and sing and that soundscapes, particularly biophony and geophony, terms coined by the ecologist, have exercised a decisive influence on our culture.

Krause was a member of the famous American folk group The Weavers. When it broke up, he formed the electronic music duo Beaver & Krause. They introduced the synthesizer into pop music in the 1960s, playing in sessions for musicians such as George Harrison, Mick Jagger, Quincy Jones and Barbra Streisand, among others. At the same time, the also worked in film, playing music in over 100 big movies, such as Apocalypse Now and Love Story. For over four decades now, Krause has traveled the world conducting a bio-acoustic study, recording and documenting natural soundscapes. He has archived the sound of over 15,000 species, over half of which have already become extinct on account of man's interference with nature. This material consists of over 5,000 hours of recordings of the sounds of nature.

After a lifetime dedicated to music and sound, what does music mean to you? How would you define it?

Because I don’t see very well, my world has always been informed by what I hear. As a young child, I was first drawn to the sounds of classical violin and composition. In my teens, I switched to guitar and learned all styles. But when I applied to American music schools in the mid-50s with guitar as my major, I was told by the interviewing professors that guitar was not a musical instrument. Shortly after university, I joined, The Weavers. After The Weavers broke up in early 1964. During that period Jac Holzman, then President of Elektra Records, introduced me to Paul Beaver. Together we formed Beaver & Krause. As a duo we introduced the synthesizer to pop music and film on the West Coast and the UK.

Paul and I realized that with the introduction of the synthesizer to musical composition, the standard definition(s) of music had also changed. So we re-defined music as the control of sound. That definition has held true even for the sound design and compositions I and colleagues have rendered since I helped initiate the field of Soundscape Ecology.

Where do you think is the common ground between the sounds of the natural world and music created by Man?

When we lived more closely connected to the natural world, we mimicked the sounds we heard coming from the forests and plains that comprised the environments in which we lived. These expressions included rhythm, melody, harmony, texture, and the structure of sound (composition). By observing the animals move, we copied their journey through space and learned to dance. In North America, there are still Native American tribes that perform a deer dance, or a bear dance, or an eagle dance…all based on an ancient need to show deference to the living world that surrounds and sustains us.

Dian Fossey’s Rwandan research camp (1967), Karisoke. By Nick Nichols, National Geographic

You have recorded more than 5,000 hours of sounds from different habitats, both marine and land, and more than 15,000 animal species. What are the greatest changes you have noticed over these five decades?

Sadly, the greatest change is the overwhelming loss of density and diversity of species almost everywhere I go these days. In some places, like northern California, where I and my wife, Katherine, live, we experienced the first completely silent spring (2015) I can ever remember in the nearly 80 years of my life. There were many birds, but they weren’t singing; it was the fifth year of the historic drought that descended on our section of the continent. The biophony (collective sound produced by all organisms in a particular habitat) returned to some degree this season likely because of the significant amount of rain we had this past winter, extremes of weather that are most likely a direct consequence of a drastically changing climate.

With so many years of experience observing these climate changes...

I should also point out that as a consequence of these climate shifts, resource extraction and land transformation, well over 50% of my natural sound archive, recorded since 1968, comes from habitats that are now either altogether silent, or where the biophonies can no longer be heard in any of their original form. For the past 25 years I have been seeking an academic home for this precious archive. It contains soundscapes most of us will never experience in the wild, again.

Then, do you defend the theory that climate change is caused by human activity or do you think that, despite the consequences of the obvious increase in CO2, the natural climate cycles are more relevant?

Based on the science I’ve read, and the many trips to remote places I’ve visited on the planet, I can imagine no other explanation for what is transpiring everywhere. We are a stubborn, illiterate, selfish, and greedy lot. And as long as we are driven to consume at the rate we do, with no limits on the degree of our avarice, my optimism fades. I’m still hopeful. Just not optimistic.

And, what do you think has contributed more to the disappearance of species: noise, pollution…?

Species disappear mostly because of our unbridled need to exploit the remaining resources of the earth for objects we simply don’t need. It is justified in many quarters by biblical mandates that have always been short-sighted and pathological to begin with. Those unfortunate echoes guide us even and especially today, despite all of the evidence screaming at us to cool it if it is our intent to thrive.

What is our culture losing by distancing itself from natural sounds?

In the end, before the forest echoes die, we may want to listen very carefully to the diminished but remaining voices of our world. We’ll quickly discover that we humans are not separate. Instead, we’re a vital part of one fragile biome.

How many of us will hear the message in time?

The whisper of every leaf and creature implores us to cherish the living world around us – which, indeed, may hold secrets of love for all things, especially our own humanity. This divine music is fast growing dim; the time approaches when we may have to bear witness as the creature spirits return for one final hunt.

What is the sound that has made the greatest impression on you?

It is actually a class of sound called the dawn chorus. Each spring season, in still-healthy regions of the world, birds tend to populate biomes in large numbers, competing not only for physical territory and mates through their extraordinary songs, but also for acoustic turf. The organization of these collective voices, which, by the way, also include insects, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals, is called the biophony. Graphic illustrations of these biophonies are called spectrograms. And when the soundscapes are healthy, the spectrograms look much like a contemporary musical score. The collective voices of these organisms evolve to occupy special niches so that they stay out of each others’ way. Otherwise their voices would be masked. And if their vocal behaviour developed to help these organisms survive, then the signals need to be clearly heard. That, I suppose, is not only my favourite and most important discovery, but it has also made the greatest impression on me. I am amazed every time I visit one of these great places and hear a healthy biophony.

Entonces, segun usted, Are animals able to synchronise their sounds like a large orchestra?

Yes. They have to. Otherwise, there would be bioacoustic chaos. These organisms have evolved to synchronize rhythm, melody, and even arrange their voices in counterpoint. The ways in which their voices coalesce in layers and textures is a form of synchronization. This can be heard in the way chimpanzees and the other great ape species beat out complex rhythms on the buttresses of ficus trees. In the way that frogs and insects synchronize their voices when chorusing.

What would you recommend in order to improve the knowledge and care of the various marine and land habitats?

I guess we need to learn to shut the hell up and get our priorities focused in order to pro-actively protect what remains of life around us.

Through your organization, Wild Sanctuary, you recorded bio-acoustic albums. These recordings have also been used to create interactive environments in museums. Could you explain what this relationship with museums is like?

When I changed careers from music to science in the late 1970s, it soon became clear to me that the publication of scientific papers, alone, meant that only a few people would ever see or hear the results of this work. So, like a few of my valiant colleagues, I decided to reach out to a larger audience through my craft and art.

After the publication of my book, The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World’s Wild Places, in French translation, Hervé Chandes, Director at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art Contemporain in Paris, contacted me in late 2015. After several encouraging exchanges he commissioned me to create a work of sound art that, instead of performing like background music, would serve as the focus of an entire exhibit and where the visual components would be informed by the sound sculptures. This was a very risky enterprise because there was no precedent on that scale and because every component of the exhibition was imagined, designed and realized literally from nothing. The installation, titled Le Grand Orchestre des Animaux, ran from early July, 2016 to January, 2017 and was one of their all-time most popular exhibitions.

You converts music into art sculpture

It is important to note that sound is not taken very seriously in western culture because we’re primarily visually oriented with most everything that informs us predicated on what we see. This exhibition changed that equation for the first time. The shadow sense (sound), is no longer ephemeral. It has finally found a fragile but seminal place in the hierarchy of the senses and thus, the fine arts.

For me, this experience has been utterly exhilarating. I had become profoundly depressed by what has been occurring in my own country, not only a dismissal of the value of the arts, but also the sciences. And I felt a deep sense of despair. With Chandes’ call and commission, and being able to work with such a dedicated and fabulous group of young people at the Fondation, I felt for the first time in a long while, a real sense of hope.

Bernie Krause in St. Vincent’s Island, Florida (2001). By Tim Chapman.

Bernie Krause: The voice of the natural world

- Bernie Krause: We need to learn to shut up and actively protect our environment" - - Alejandra de Argos -