- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

Vienna is this year commemorating the centenary of the deaths of Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Otto Wagner and Koloman Moser. The celebrations kick off with a Schiele retrospective at the Leopold Museum: oils, watercolours, drawings and gouaches alongside photographs and poems. In all, over 200 breathtaking works of art divided up by theme. Egon Schiele died at the age of 28. The Leopold Museum in Vienna, which houses the largest collection of his work in the world, is now honouring the 100th anniversay of his death with an unforgettable exhibition. In one glass display case, there is a photograph of the artist, lying on his deathbed in a white shirt, his left arm bent lazily to support his head. He would look every bit the young man snoozing in the sun were it not for the wild flowers scattered over his body.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

Egon Schiele, Seated Woman with Bent Knee, 1917. Narodni Gallery, Prague

Vienna is this year commemorating the centenary of the deaths of Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Otto Wagner and Koloman Moser. The celebrations kick off with a Schiele retrospective at the Leopold Museum: oils, watercolours, drawings and gouaches alongside photographs and poems. In all, over 200 breathtaking works of art divided up by theme.

Egon Schiele died at the age of 28. The Leopold Museum in Vienna, which houses the largest collection of his work in the world, is now honouring the 100th anniversay of his death with an unforgettable exhibition. In one glass display case, there is a photograph of the artist, lying on his deathbed in a white shirt, his left arm bent lazily to support his head. He would look every bit the young man snoozing in the sun were it not for the wild flowers scattered over his body. Just a few hours earlier, Schiele had finished a sketch of his wife as he watched her from this bed. Edith, pregnant with their child, has her heavy head resting on a pillow, her eyelids drooping. None of them would live. Edith was to die of Spanish flu, whilst being painted by her husband, on the 18th of October 1918. Schiele, who had also already contracted the disease, would die three days later.

Marta Fein, Egon Schiele's Deathbed, 1918. Leopold Museum, Vienna

As a child, Schiele (born 1890) started out drawing the trains he watched in Tulln, a small city on the Danube, where his father was station master. He entered the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts at 16 and from then on, he remained inseparably tied to Austria's capital. Between 1898 and 1918, Vienna was both the finale and the prelude to many things. During the second half of the 19th century, this opulent hub of the Austro-Hungarian Empire saw the building of the Ring Road palaces while life pulsed and revolved around the operas and infectious waltzes of Johann Strauss II. At cafe tables all over the city, people read and wrote about themselves, much like characters out of a Joseph Roth novel, in the twilight of their empire. And still, slowly, Vienna was declining and falling all around them.

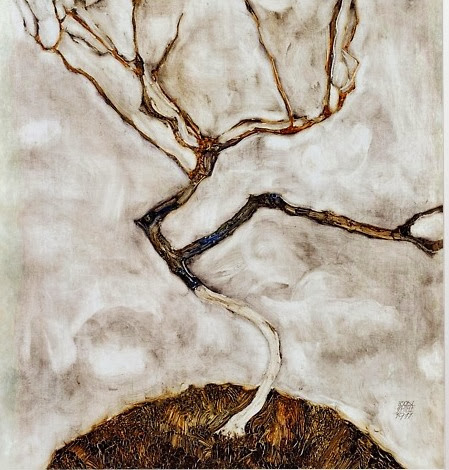

Egon Schiele, Small Tree In Autumn, 1911. Leopold Museum, Vienna

Sex and death

It was against this backdrop of an empire on the verge of collapse that the precursor to a new century was ushered in. It entailed an explosive surge in intellectual pursuit and artistic creativity throughout all fields. See the architecture of Otto Wagner, Josef Hoffmann and Adolf Loos. Hear Mahler's symphonies seemingly marking out the rhythm of a different spiritual beat. It was the time of writers like Kraus, Trakl and Schönberg and of philosophers like Wittgenstein. As regards painting, Gustav Klimt, the first president of the Secession movement, had started out as a conventional history painter but was now on the lookout for new horizons. Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele were to represent the second generation of this artistic renovation and become the exponents of Austrian Expressionism.

Egon Schiele, Sitting Semi Nude With Blue Hairband, 1914. Leopold Museum, Vienna

The decadence of 1900's Vienna was an emotive catalyst that veered between two obsessions: sex and death. Old Austria was not just a void but a constancy that dissimulated the void. Nihilism made way for a new state of mind and a new bravado. Sigmund Freud discovered that pain created specific problems and conflicts that would not resolve themselves. He wrote The Interpretation Of Dreams and Studies On Hysteria which Schiele became obsessed with. Exploration of the "I" and sexual identity were all that interested him and this spilled over onto his canvasses.

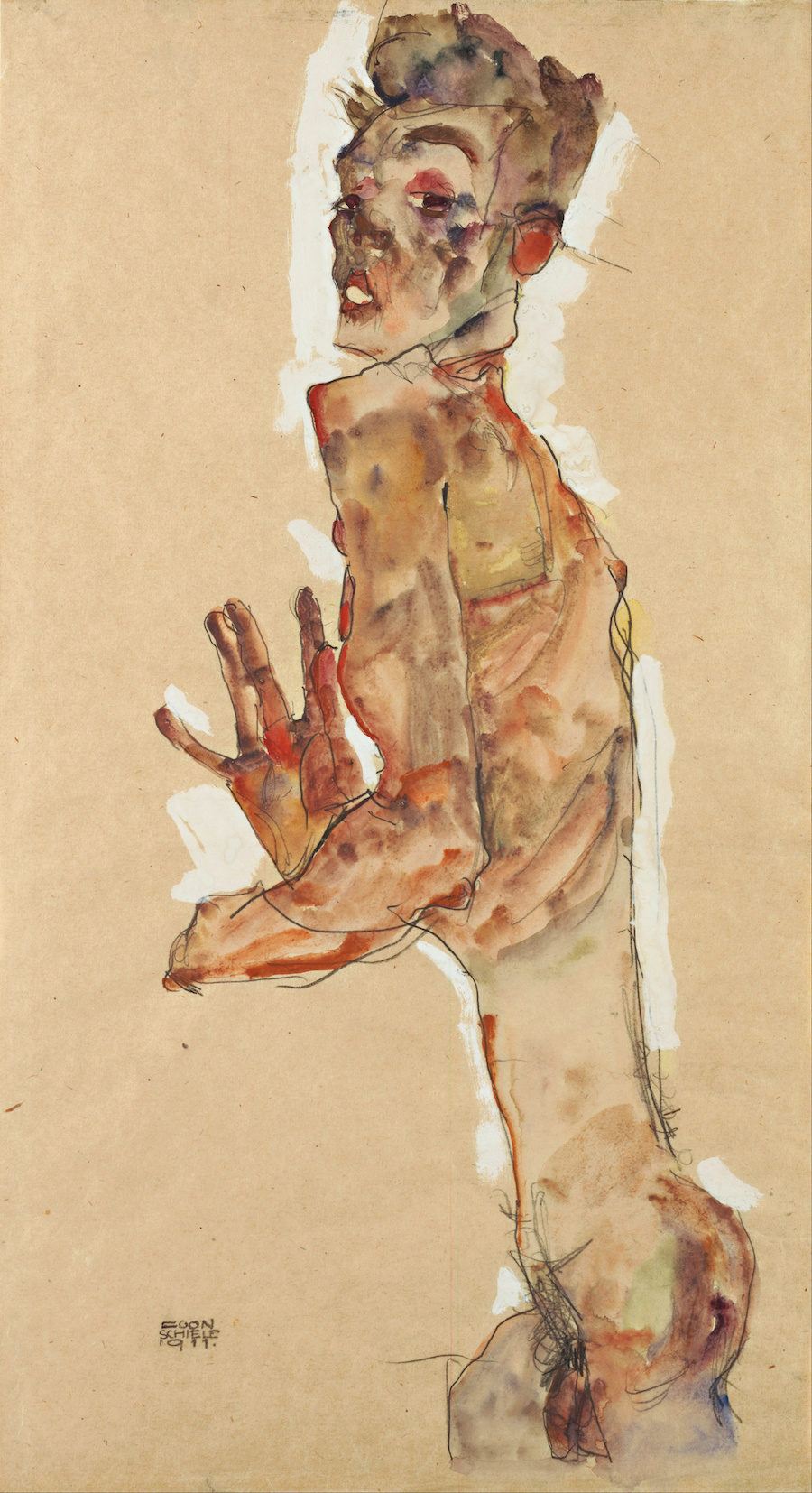

Between 1910 and 1918, Schiele addressed various psychological topics. He left traditional portraiture behind, having pushed it to its absolute limits and, as Richard Avedon said, " he broke the mould and turned up the volume to scream pitch". Schiele's scream came from inside haggard, twisted, satanic bodies that terrified the society of his day. He was often his own model, gesticulating, mouthing words, his hair bristling and a menacing look in his eye, painting hands sharpened like spiders and which rarely depicted a thumb. He cut off his compositions to look almost mutilated, pushing the bodies of his subjects right into the corners of the canvas. His approach was radiacally "flat", like American art of the 1940's. Backgrounds didn't exist and bodies were suspended in the void, alone. Even the paper he used, from 1910 onwards, had something of the past-its-sell-by-date about it, a high concentration of lignin giving it a particular pale brown quality that could not withstand exposure to light. He sometimes outlined them with a white border, as if they had an aura around them. For Schiele, bodies emanated light: "I draw the light that comes from bodies."

Egon Schiele, Self-portrait With Splayed Fingers, 1911. Leopold Museum, Vienna

Egon Schiele was all but forgotten during the 1930's but not so much so that the Nazi regime would neglect to include him on their list of degenerate artists. He was, however, rediscovered after WWII as a fundamental figure in modern art. His mutant, narcissistic persona would go on to attract other like-minded egos while later contemporary personalities such as James Dean and David Bowie would fall under his spell.

Egon Schiele, Self-portrait, 1912. Leopold Museum, Vienna

In the vast majority of his over 2000 drawings and 300 paintings, Schiele transforms the body - particularly the female one - into a chilling merchandise of desire. Skirts wide open, exposed genitals, prostitutes, his 14 year old sister, lesbian couples, priests, nuns, postures and bodies as if from an extermination camp. None of them has a real face. They are, rather, stunned masks with a look of the lost about them.

Egon Schiele, Lovemaking, 1915. Leopold Museum, Vienna

The aesthetics of the grotesque

One might say that Schiele was a master of the aesthetics of the grotesque. Up until then, in works such as Courbet's The Origin Of The World (1866) or Japanese prints, sex had never been treated in such a sordid manner. Why then do Schiele's paintings move us with their beauty? Why do his stray faces, enraptured gestures and anxious hands seem, at times, to possess the serenity of a Russian ballerina frozen mid-performance?

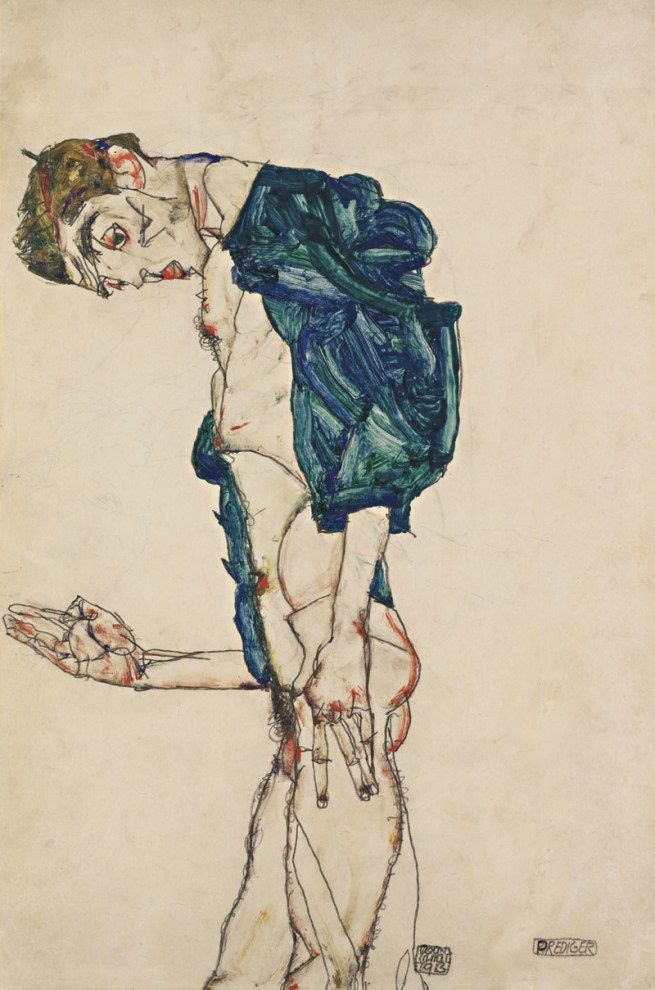

Egon Schiele, Preacher (Nude With Teal Shirt), 1913. Leopold Museum, Vienna.

The answer lies, arguably, in the virtuosity of Schiele's technique. Few artists have managed to convey so much with just one stroke, or even at times, a scribbled line. They ranged from sharp to caressing and from tense to delicate, whether hastily sketched or profoundly deliberate, broken or fluid. But above all, Schiele was prodigious in his use of colours, wholly independent of Nature's own. He used greens and purples, lilac, mauve and reds for human skin. His bodies looked ill but the colourways were sublime.

Albrecht Durer, Wing Of A European Roller, 1512. Albertina Museum, Vienna.

A short distance away from this exhibition in the Museums District is the Hofburg Palace with its still snow-covered gardens, Habsburg library and imperial steel filigree glasshouse and so we arrive at the Albertina Museum. In the rooms containing this collection, Albrecht Durer's watercolours rub shoulders on the walls with those of Schiele. 400 years may separate them but, regardless, they are both stitched from the same cloth of infinite blues, oranges or greens and the same mastery of line that edges each feather on the wing of Durer's birds or the body of Schiele's figures. In these days of strange and seemingly random censorship when photographs of prisoners are taken down at a Madrid art fair or posters for Schiele exhibitions are banned for obscenity in London, Cologne and Hamburg, it's well worth coming to Vienna. Sometimes, it takes raw, naked beauty to make sense of things. As Schiele himself wrote at the bottom of one of his watercolours, "I don't think there's such a thing as modern art. It's just art and it's eternal."

Egon Schiele, The Embrace (Lovers II), 1917. Belvedere Gallery, Vienna

EGON SCHIELE ~ The Jubilee Show

Leopold Museum

Museumsplatz 1, Vienna

Curator: Diethard Leopold

Until 4 November 2018

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Egon Schiele, beauty and the chasm between - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

In the winter of 1910, Amedeo Modigliani was accompanied by Anna Akhmatova on his strolls around Paris where, together, they discovered the Louvre's Greek and Egyptian art collections, moulds from Angkor in the Trocadero's Indochinese pavillion and black masks brought from the Ivory Coast. Modigliani would later draw Akhmatova's Slavic silhouette with sparse outlines borrowing on the Egyption art he so wanted to immerse himself in. The sketch portrays her as solemn, serene, regal even, her posture only softened by a slight inclination of the head. Later still, this pair of young expat lovers in pre-WWII Paris, would recite Verlaine's poetry together duet-style. Akhmatova described their relationship thus in 1911: “We both read Mallarmé and Baudelaire.

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

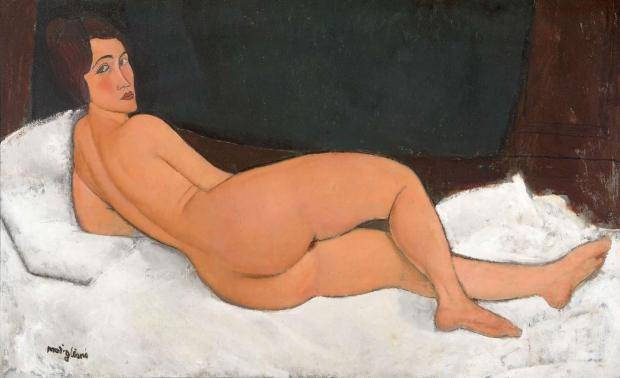

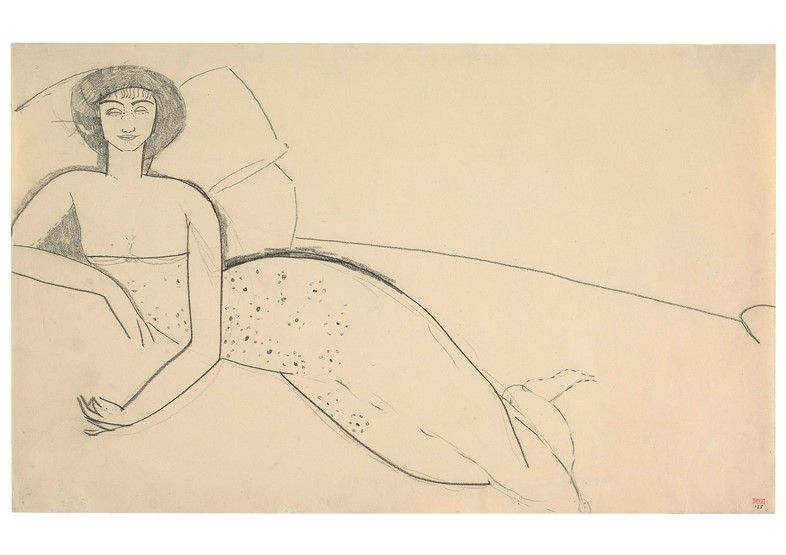

Nude, 1917

In the winter of 1910, Amedeo Modigliani was accompanied by Anna Akhmatova on his strolls around Paris where, together, they discovered the Louvre's Greek and Egyptian art collections, moulds from Angkor in the Trocadero's Indochinese pavillion and black masks brought from the Ivory Coast. Modigliani would later draw Akhmatova's Slavic silhouette with sparse outlines borrowing on the Egyption art he so wanted to immerse himself in. The sketch portrays her as solemn, serene, regal even, her posture only softened by a slight inclination of the head.

Later still, this pair of young expat lovers in pre-WWII Paris, would recite Verlaine's poetry together duet-style. Akhmatova described their relationship thus in 1911: “We both read Mallarmé and Baudelaire. But he never read me Dante because at that time I couldn't speak Italian”. She was 21 and just starting to write her very first poems in Russian. He was a 26 year old Bohemian artist and still a complete unknown. Modigliani is often remembered as an addict of alcohol and marijuana but, almost never, as a poetry or bookaholic.

Woman reclining on a bed (Akhmatova), 1911

Born in Livorno in 1884, he had been steeped, during his study years in Florence and Venice, in Classical Art and this immersion left an indelible mark on him. He arrived in Paris in 1906 and devoted what remained of his life to art. In Montmartre, he was just another immigrant along with the likes of Apollinaire, Picasso, Derain and Diego Rivera but, in his case, an Italian Jew suffering from tuberculosis and an exotic pariah amongst many other pariahs in that small, cosmopolitan republic of artists and writers. He may have been living in Paris but he was Italian through and through: in his dress (corduroy or velvet suits with knotted scarves), in his seduction techniques, in his understanding of beauty, in his wandering freely ... in his reading and reciting of Dante's Divine Comedy and Inferno until the day he died.

In the early years and similarly to other young geniuses like Picasso or Braque, he began painting in the style of Cézanne. But while Picasso and Braque would retain the Post-Impressionist's simplification in volumes, Modigliani, also heavily influenced by Toulouse-Lautrec and Whistler, focused on portraits but still made use of Cézanne's concept, brushstrokes and very nearly monochrome palette.

Head, 1911-1912

But it was in 1909 on meeting Brancusi that Modigliani left painting behind and between 1910 and 1914 he identified as a "sculptor". Together, he and Brancusi would scour the outskirts of Paris for materials to steal and bring back to the rented apartment they shared in Montparnasse. He began to chisel female heads directly from blocks of pilfered stone. He wanted to liberate sculpture from the dead end down which Rodin had lead him: so much modelling, so much clay. He thought chiselling should be done "live" the way the Ancient Greeks had done it, by breaking into a slab of stone in order to draw from it deities with African or Cambodian features. In the evenings, he would illuminate these heads with candles, turning his studio into a sort of primitive temple of the occult. In the Tate's current Retrospective, there is one room dedicated solely to his sculptures and it is a room that takes your breath away. In it, nine of his 29 sculpted heads rise like totem poles enclosed in their glass cases and arranged in a slantwise dance. The last time these heads were displayed together was at the 1912 Autumn Salon and Modigliani was then still alive. Lipchitz said of them: "He conceived them as a whole and set them up one in front of the other like the pipes of an organ in order that they produce exactly the music he wanted to convey."

The influence of non-Western sculpture in the Paris of Modigliani's day was radical. In 1906, Gaugin's Retrospective at the Autumn Salon shocked the Parisian avant-garde, especially the wood reliefs carved during his latter years in Polynesia, with their marked primitive and feral imprint. That same year, artists such as Derain, Vlaminck, Matisse and Picasso started to buy African art. All of this signified a turning point in Modigliani's career and, around 1914, he suddenly stopped sculpting. The dust particles released into the air he inhaled while chiselling were only exacerbating his disease and perhaps, also, it was occasioned by war being declared that year and his permanently dire financial straits.

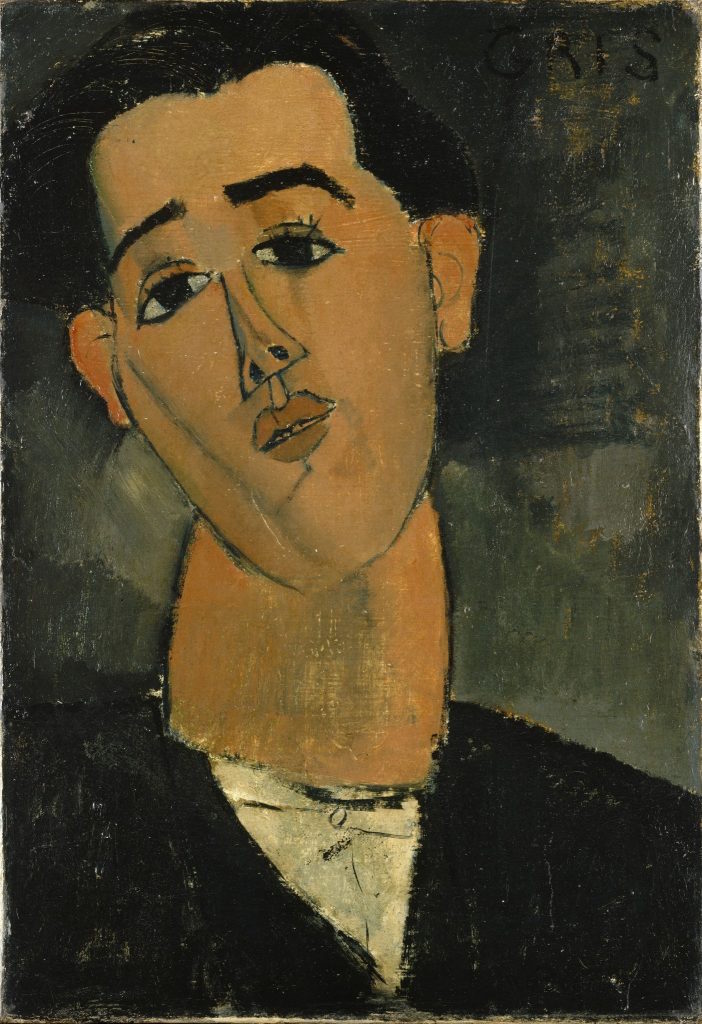

Juan Gris, 1915

Painter of artists' portraits

Between 1914 and 1920, the year of his death, Modigliano did only paintings and he did so profusely. In cafés such as La Rotonde, Le Dôme and La Cloiserie des Lilas he chose artists and writers as his models. This is also the time of his complex and serious relationship with the South African journalist Beatrice Hastings. Both were great readers, travellers and socialites. Both shared an addiction to alcohol - whiskey for her, red wine for him - and to hash. At the beginning of the 20th century, Montparnasse had become a ghetto for artists on the fringe of many things and beyond the reach, perhaps, even of the war that was wreaking profound changes on Parisian life. Choosing to be a painter in the artistic community of Paris was his way of trying to integrate his own lifestyle into his art.

This body of portraits, among which are those of Juan Gris, Celso Lagar, Picasso, Diego Rivera, Chaïm Soutine, Derain, Matisse, Cocteau and Max Jacob has many common denominators: subject matter tight to the frame, face-frontal poses and a fixed gaze. Nothing about them allows the spectator to escape the stare of those eyes except, perhaps, their recurrent lack of irises and pupils. Léopold Survage asked, on viewing the portrait that Modigliani had just finished of him: “Why did you only give me one eye?" Modigliano replied: “Because we look at the world with one eye and with the other, we look inside ourselves."

Marie, 1918

With Cubism now an emerging new art movement, Modigliani tried to create a "synthetic" image of the human being: outlined faces with the bridge of the nose and the eyebrows accentuated. The palette was dense but limited and the surfaces luminous. It was painting that came from some spiritual and intimate place and also from a commitment to integrating multicultural sources. Jean Cocteau summed it up perfectly: “First, everything took shape in his heart. The way he drew us around a table at La Rotonde, incessantly: the way he judged us, sensed us, loved us, discussed and argued with us. His drawing was a silent conversation. A dialogue between his sketch and us."

Scandalous nudes

Modigliani worked furiously, with no let-up, no holds barred. He painted by instinct, as dictated by his Italian genetic makeup and all whilst spitting out blood. Three years before his death, he painted his famous female nudes which were banned for indecency in 1917 - now a century ago - at the inauguration of the only solo exhibition of his work during his lifetime, at the Berthe Weill Gallery. They are, perhaps, the highlight of this Tate exhibit but why so? What produces this magnetic pull? Is it Modigliani's deep aesthetic imprint mixed with a blatant eagerness to provoke desire in the onlooker or was it the £113 million his "Reclining Nude" sold for at Christie's in 2015?

By now, Modigliani was no longer portraying a distant, ideal kind of beauty but a concrete woman: prostitutes, lovers or women who earned their living by posing for him. His models now were modern women with short haircuts, fashionable jewelery and makeup mimicking that of the cinema starlets of the day; women who look at the viewer and accuse him of voyeurism. The distance that existed in the canvases of yesteryear - from Giorgione to Manet's Olympia - disappears. Their bodies are firmly in the foreground, giving the impression of intimacy, as if they would allow us to touch them.

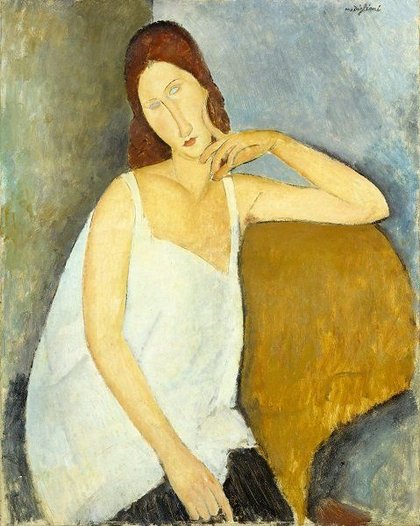

Jeannette Hébuterne, 1919

And after this sublime room, the exhibition closes with soft colours, pale light and the sweetest of subjects. These are the paintings of the time Modigliano spent in Nice and Paris with Jeanne Hébuterne, his common-law wife and young mother of his daughter, who was with him throughout his final demise. Shut away in their workshop, surrounded by sardine cans and bottles of wine, Jeanne painted Modigliani while he was dying. He was 35. She was 21. In the last room there is a portrait of Jeanne wearing an ample smock blouse flowing over her nearly full-term pregnancy. It has an air of Parmigianino's Madonna With The Long Neck but nothing about it hints that, just a few weeks later, she would throw herself and her unborn child off the balcony of her parents' apartment. She could not bear to go on after Modigliano's death, her lover with the christian name Amedeo from the House of Savoy and who, the previous day, had been buried with all the honours of a prince by an entourage of painters, writers, actors and musicians in Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

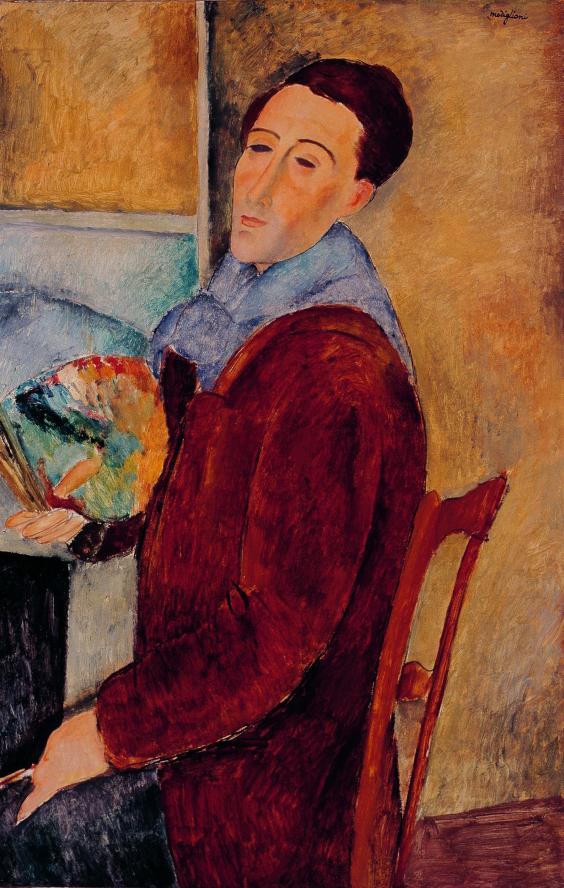

Self Portrait, 1919

Modigliani

Tate Modern

Curators: Emma Lewis and Nancy Ireson

Bankside, London

Until 2nd April 2018

Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne being viewed by an exhibition visitor. Modigliani, Tate Gallery

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Modigliani, a painter with one eye looking inwards - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Marta Sánchez

As well as being one of today's most highly regarded artists (something that, incidentally, would have greatly annoyed him), Sigmar Polke is the personification of the versatile, nonconformist artist creator. His work runs the gamut of all the styles present in contemporary art, from Realism to Pop Art and from Arte Povera to pieces in whose creation a deliberate happenchance intervenes. However, what makes Polke one of the most interesting artists of the last four decades is that he never limited himself to just one single material or product (oil, acrylic, collage ....) on whichever mount or frame he chose to display them. In his workshop, he was given not only to mixing it up with all kinds of media but also to combining many of the components of 20th century culture.

As well as being one of today's most highly regarded artists (something that, incidentally, would have greatly annoyed him), Sigmar Polke is the personification of the versatile, nonconformist artist creator. His work runs the gamut of all the styles present in contemporary art, from Realism to Pop Art and from Arte Povera to pieces in whose creation a deliberate happenchance intervenes.

Sigmar Polke. Fredrik Von Erichsen—dpa/Landov - Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

However, what makes Polke one of the most interesting artists of the last four decades is that he never limited himself to just one single material or product (oil, acrylic, collage ....) on whichever mount or frame he chose to display them. In his workshop, he was given not only to mixing it up with all kinds of media but also to combining many of the components of 20th century culture. As a result, his work is full of nuances, and oftentimes poetry as an added ingredient, along with his very firm commitment to social commentary verging on whistleblowing.

From stained glass window apprenticeship to the Düsseldorf Arts Academy

Stained glass window by Sigmar Polke. Grossmünster Church. Photo: Roland zh

Polke was born in Silesia, now part of Poland, in 1941. His family were forced to flee to East Germany after his homeland's defeat in World War II and again in 1953, this time into neighbouring West Germany. With his family now settled in Düsseldorf, Polke began his artistic career learning the techniques of staining glass windows but soon exchanged this for Fine Arts studies at the Düsseldorf Arts Academy. Sometimes it's of the essence to find yourself in just the right place at just the right time which is precisely what happened in Polke's case as he was able to forge his talent under the tutorship, and influence, of professors such as Joseph Beuys, Karl Otto Götz and Gerhard Hoehme.

By 1963, Polke had already allied himself with several classmates and friends, amongst them none other than Gerhard Richter, to launch his first ever collective exhibition in one of the city's empty slaughterhouses. It was the starting point for both their careers and they would soon conceptualize something that would from then on be definitively linked to their art: Capital Realism.

Capital Realism, alquemy and provocation

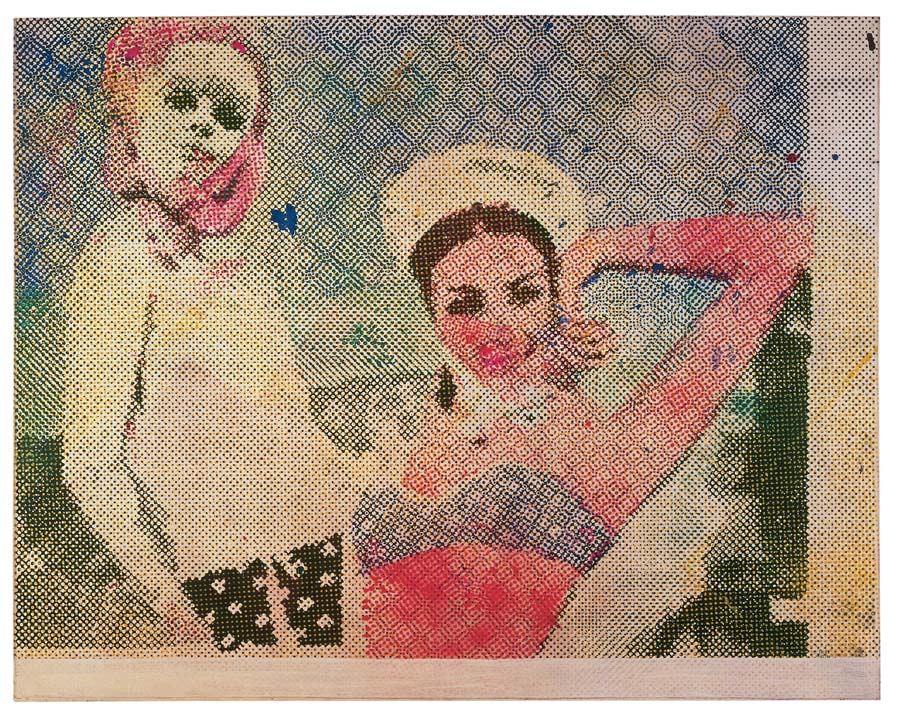

Freundinnen (Friends) 1964-65 © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. www.alexkittle.com

Capitalist Realism was inspired by Socialist Realism, the "official" art movement of Lenin's USSR and Mao's China. During these years, Polke intelligently mixed parameters inherited from New American art (heavily influenced by Warhol and Lichtenstein) with a stale realism riddled with stereotypes and symbols, like the swastika that was then banned in Germany. The result was a series of works denouncing not only Germany's absorption into a consumerist and capitalist maelstrom but also the stagnation, totalitarianism and omnipresence of the governments ruling the Communist bloc. This period is marked by iconic works such as "Freundinnen" (Friends) from 1965.

Polke was also known as the alquemist. In his studio, he mixed materials, media and products to give new meaning to reality and to art. These works, with formats ranging in scale from the smallest to the most monumental, differ according to who is looking at them, from which angle or distance and even the mood they happen to be in at the time. But Polke's alchemist zeal was not limited to just the purely technical field. As well as blending seemingly impossible products with pigments, from the 60's on he began to merge political and critical elements into his creative output, these layered with the German sarcastic tradition inherited from artists like George Grosz.

Buyer, I dare you

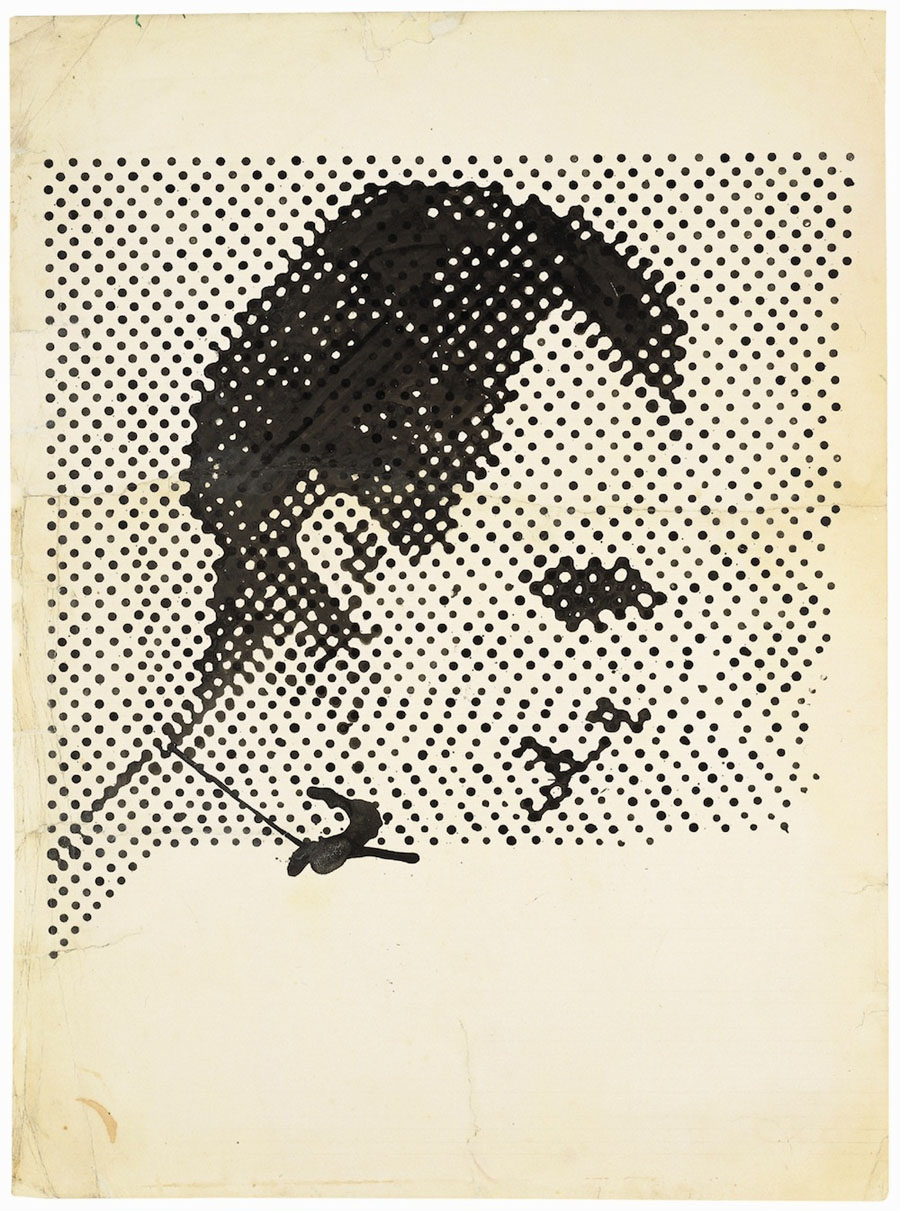

Sigmar Polke Raster Drawing (Portrait of Lee Harvey Oswald) 1963 © The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Tate UK

This type of experimentation gave rise to pieces full of political intent. During this time, Polke produced such provocative works as his famous portrait of Lee Harvey Oswald, painted in 1963. After seeing Warhol's well-known prints of the multiplied faces of Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy, Polke decided to do the same with one of the then most hated people in America: the alleged murderer of President Kennedy. His attitude was akin to a challenge to society, a way of saying to the world: "Here you are then. Buy it if you dare".

The LSD years

Sigmar Polke. Alice im Wunderland, 1972. Private Collection. Photo: Wolfgang Morell

© The Estate of Sigmar Polke by SIAE 2016. Eigth Art Projects.

The 70's were for Polke, as for so many other artists, a decade of experimentation. He went to live on a farm commune where he dabbled in drugs like LSD and magic mushrooms, in addition to contributing to the creation of collective artworks. They are fruitful years in terms of his creativity. Polke produces some quite powerful works based on mixing and overlapping new materials. And at this time, they also match the artist's photographs that he was manipulating using chemical agents in a seeming attempt to portray the human mind as altered by drugs.

In 1972, Polke takes part in the iconic documenta 5 in Kassel, Germany and from that moment on, his work achieved a worldwide popularity that continues to this day. The 70's also see him travelling extensively to the likes of Afghanistan and the Lebanon where his camera captured moments that he would later transform into works of art.

{youtube}Coia8F64KjI|900|506{/youtube}

The journalist Sarfraz Manzoor conducts an exhaustive review of the retrospective exhibition Alibis: Sigmar Polke (1963-2010) at the Tate Modern, London

Rupture and rebirth: Art as a reflection of a society in turmoil

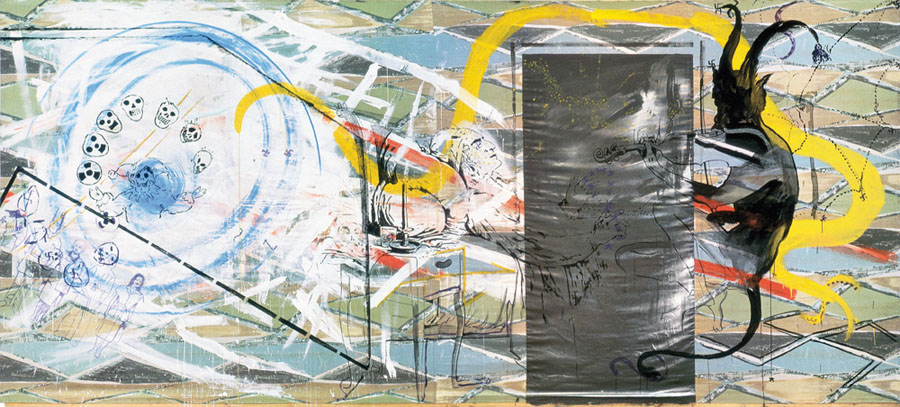

Sigmar Polke. This is how you sit correctly (after Goya), 1982. Private collection, Baden Baden. Image viewable at www.artchive.com.

Already by now a world-renowned artist, at the start of the 80's Polke is rethinking his art and decides to break with all that went before in order to start again from scratch. The experimentation in his art becomes more troubling, explosive and radical. Over this period, he uses disturbing and even dangerous products to carry out his works: meteorite dust, arsenic-based toxic paint, uranium, ..... Polke draws on artists of the past who portrayed the horrors of war and human behaviour. Among them, Goya's work exerts a particular attraction and the Spanish artist's imagery appears in works like "This is how you sit correctly (after Goya)" from 1982.

Meanwhile, against the backdrop of the Cold War and the tense relations between world superpowers, the unstable political scene was giving much cause for alarm. This state of affairs can be seen reflected in Polke's work depicting a changing, nightmarish world during these years.

Paganini, 1982. Saatchi Gallery, London

In his later decades, Polke's work continued to evolve along these same lines. Without ever abandoning his references to Germany's past, evident in his portraits of young Nazis or the swastikas hidden in works such as "Paganini" from 1982, his continuous experiments with products, materials, transparencies, projections and graphics generated dozens of masterpieces, works that now constitute one of the most compact, coherent, shocking and provocative artistic trajectories of 20th century art history.

Notable exhibitions

Following the 1972 documenta 5 exposure that catapulted him to fame, Polke began a frequent chain of joint and individual exhibitions. Initially, his work was exhibited in German galleries (and later museums) which then moved on to cities such as Paris, New York, Washington and London. Polke died in 2010 but the world's greatest museums still continue to mount exhibitions to showcase the magnitude and diversity of his oeuvre.

- New Works - Sigmar Polke. Museum of Modern Art of the Ville de París, 1988. One of the first exhibitions outside Germany which marked the beginning of a worldwide dissemination of his work.

- The Three Lies of Painting - Sigmar Polke. Art and Exhibition Hall, Bonn, 1997. This exhibition subsequently moved to the Berlin National Gallery for Contemporary Art at Hamburger Bahnhof (1997-1998). It was based on a work of the same name from 1994.

- Retrospective. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMoMA), 1990. This was Polke's first ever retrospective in the Unites States. The exhibition subsequently moved to the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution (Washington), the Museum of Contemporary Art (Chicago) and the Brooklyn Museum (New York).

- Sigmar Polke - Photoworks. When Pictures Vanish. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (1995). This exhibition was a compilation of the artist's photographs taken between 1960 and 1995.

- Retrospective - Sigmar Polke. Museum Frieder Burda - Baden Baden (Germany), 2007.

{youtube}_m4eHWc28io&t=65s|900|506{/youtube}

- Alibis - Sigmar Polke: 1963 – 2010. MoMA (New York). Later, Tate Modern (London), 2014-15.

{youtube}F_jEzpQJygw&t=261s|900|550{/youtube}

- Sigmar Polke - Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 2016.

{youtube}lb9k5EBccsE|900|506{/youtube}

- Sigmar Polke - Music from an Unknown Source. Museum of Modern Art, Mexico, 2017.

{youtube}LbA4MlDhdZg|900|506{/youtube}

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Sigmar Polke: Biography, Works and Exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca

It is highly likely that, for many people, philosophy ultimately amounts to nothing more than an ambiguous word, used as it is in very varied contexts to refer to different things. As a common linguistic expression, the word "philosophy" doesn't have a precise substance to it and nor does it allow for a generally accepted or acceptable brief definition. We hear repeatedly about the philosophy of an electoral programme in politics or the philosophy of a marketing strategy for a product in the fields of commerce or industry. We also hear it said, in our everyday language, that it is best to look at life philosophically or that each person has their own philosophy on life. Lastly, it is said that philosophy is also a type of knowledge, somewhat vague or even obscure for some, engaged in or indulged in by certain individuals not unknown for a certain smugness and distinguishable by their aura of esotericism and mystery.

|

Contributor: Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca, |

|

It is highly likely that, for many people, philosophy ultimately amounts to nothing more than an ambiguous word, used as it is in very varied contexts to refer to different things. As a common linguistic expression, the word "philosophy" doesn't have a precise substance to it and nor does it allow for a generally accepted or acceptable brief definition. We hear repeatedly about the philosophy of an electoral programme in politics or the philosophy of a marketing strategy for a product in the fields of commerce or industry. We also hear it said, in our everyday language, that it is best to look at life philosophically or that each person has their own philosophy on life. Lastly, it is said that philosophy is also a type of knowledge, somewhat vague or even obscure for some, engaged in or indulged in by certain individuals not unknown for a certain smugness and distinguishable by their aura of esotericism and mystery.

The fact of the matter is, especially for those who have not yet taken a serious, personal interest in philosophy as an intellectual discipline, that whatever common denominator, if any, there might be amongst the multiplicity of applications of the term "philosophy" and its concepts, this has not made itself widely known. Even granting that differentiating between philosophy as a vital attitude and philosophy as theoretical knowledge, let me focus, for now, on the latter meaning whilst acknowledging that the complexity and difficulties in reaching a clear and precise concept of what philosophy actually is will persist. One might be able to see things more clearly by making a comparison.

If we ask ourselves what biology, mathematics and history are as intellectual disciplines and what they are used for or why they exist, defining them is not an insoluble problem. Thus, biology is essentially the study of living matter and organic phenomena, using the observational method. Its results are useful in the fields of medicine, industry, agriculture, etc. There is no special difficulty in answering the question "What is biology?" But is it the same in the case of philosophy, even when understood as just an intellectual discipline? Even after 27 centuries in existence, anyone would be hard pushed to provide such a clear answer to the questions: "What is the purpose of philosophy?" or "What is the reasoning behind this age-old intellectual pursuit?"

Perhaps someone reading this might be expecting me to reveal the "right" concept of what philosophy is, to resolve all the confusion and to provide a magical answer that would eliminate any doubt. Forgive me for telling you that I don't intend to even try. And not just on the hackneyed pretext that it's not possible to solve such a complex and thorny issue in the short space of an article but because I consider myself highly unlikely to succeed at an endeavour where many illustrious teachers have failed before me.

Given the changes that the concept of philosophy has undergone throughout history, along with the breadth and variety of cultural products that have designated themselves "philosophy", it becomes very difficult and risky to construct or to coin a univocal, definitive and universal concept of what philosophy is. The formulation of its tasks and objectives has been modified according to historical circumstances and as each particular science has appeared and evolved. Which is why, from a systematic point of view, it isn't entirely possible to determine philosophy's scope of study, objectives and methods with any set know-how or science and in the established way, from the word go. The defining characteristic of philosophy as an intellectual discipline is, therefore, going to be the crux of its task in having to "critically" justify itself in the selfsame way that reason develops in its attempt to understand the world.

In very general terms, the vast majority of the great philosophers of the past constructed their philosophies from a specific "modus operandi", or rather from a certain "method" that distinguished philosophy from other fields of knowledge, particularly the sciences. Thus, while each individual science was concerned with one given and fixed objective or with the one specific problem that constituted its speciality, be it organic phenomena in the case of biology for instance, or the study of fossils in that of paleontology, or atmospheric phenomena in that of meteorology, philosophy's "speciality" was, one could say, "the totality of what is", or in other words, the sense of the whole, the being of the universe, taking universe to mean the whole, integral ensemble of everything that is, of the universals that exist within it and their mutual relationships.

Methodologically, our philosopher was not (strictly speaking) interested as such in each and every object or problem that makes up the universe in themselves, in their separateness and specificity but rather in the sense of their interrelationships, what each thing "is" together with or in opposition to the rest, its position, role and rank in the grand scheme of things and what each thing represents in the entirety of universal existence. The scientist, bound by the self-imposed constraints of his method, has always positioned himself within the universe, marking off a portion of it with what he has made the object of his study. But, in so doing, he automatically broke the web of interdependencies in which every object cannot help but find itself, blocking out the integrity of our lived world as it appears to us inside our natural and spontaneous mindset. This is precisely what the philosopher was therefore looking for: a totality, an idea, an all-encompassing conception of the whole or of this innately-sensed universe in which we go about our daily lives, not as a jumbled, bitty mess of things but as something complete and unified.

Perhaps at first glance, these aspirations and attempts by past philosophers to think of the sense of the whole as a systematic and unified conception of all reality might seem, to those of us in the 21st century, to have something of the megalomaniac about them. In fact, these days, such an undertaking is still considered to be an illusory task of impossible and unbridled pretensions even though, granted that it seeks to find a sense of the whole of the universe and of life, philosophy is just a discipline that is neither more nor less modest than any other. Because that Whole, so sought-after by philosophy, was not thought of as a numerical set of existing things, nor was it made up of the sum of all knowledge from all the sciences. Rather, it would confine itself to pursuing the universal in each and every thing, its essence, the factor that makes every object connect with and fit into a totality, thus acquiring a fullness of meaning.

Hegel - surely the last of the great systematic and metaphysical philosophers - said that only philosophy made us see the world as it is, as a whole, and not illusively as the separate things that might appear in it; isolated, autonomous, unrelated, meaningless. As opposed to the sciences, philosophy would thus have a role of the highest order to fulfil and that would be none other than to offer a concept of the whole, a "metaphysical" notion of the beingness of the world and the meaning of life.

One of the arguments put forward by contemporary critics of this metaphysical philosophy of the past has been that, if the validity of a knowledge is measured by the effective results obtained in whatever subject it addresses, then philosophy's progress over its 27 centuries of existence and endeavour does not seem to have achieved anything at all effective and almost nothing close to what it claimed to be researching. Because, where is this progress? Who today possesses this unified and universal concept of the sense of the whole of the Universe that is more or less commonly accepted? What is this concept of the world itself that philosophy presents to humanity today? What are the core values that philosophy proposes in order to morally orient the actions and lives of men and women today?

The answers to these questions do not allow for any one consensus of opinion on the systematic achievements of past philosophers regarding philosophy as the "science of knowledge", or an intellectual discipline. For precisely this reason, the only possible answer today to the question "What is philosophy" should start with a refusal to distinguish philosophy as intellectual discipline from philosophy as an attitude to life. Philosophy is and remains, first and foremost, that - an attitude, an outlook, man's way of existing as he confronts the world. But it is an attitude that takes the form of aspiration, desire, restlessness, anxiety, and a "desire to know", to understand, to appropriate wisdom. And this is precisely what the term "philosophy" means in ancient Greek - "the love of knowledge". However, as a quest for a general sense of the world and for reasons that guide our behaviour and our expectations, it cannot, strictly-speaking, claim any definitive theory of anything. Instead, it probes and analyses in an exhausting search for itself and in the continual pursuit of the multiple, changing meanings of things. And even more so given that the world, society, human behaviour and life taken altogether are not static. They are, rather, living entities in a progressive and integral state of flux covering an infinity of dynamic interrelations.

Even so, there will still be someone asking, and they would be perfectly in keeping with the pragmatic and utilitarian spirit of our times: "What is philosophy for?"; "Which of our needs does it satisfy?"; "Why all this searching for meanings and the value of phenomena and processes that the sciences are already dealing with better and more rigorously?"; "Why not just do what the vast majority of people do which is just live their lives in peace, ignoring all the vagueness and ambiguity that philosophers tell us about?"; or "Perhaps there's more to all that searching than just a subtle way of complicating our lives and most definitely everyone else's as well?"

Kant said that whoever philosophises does so at the insistence of his own reasoning's dynamism. In other words, his mind will not be pacified with any old explanation, aspiring, rather, onwards and upwards in search of supreme syntheses and the most penetrating, all-encompassing meanings. Aristotle, for his part, thought that every human being, in one way or other, is a philosopher by nature because, in his view, every human being wants to know. And Plato asserted that when this desire for knowledge and this love of wisdom (which are the essences of philosophy) happen to someone, stirring and awakening in them, then it is usually as a result of that person's painful, prior realisation that they don't know, that they don't understand and that they "need" to know in order to be. It would, therefore, be in that perception of one's own ignorance and "lackingness" that the root of knowledge, and hence philosophy, lies.

And it is because of this deficiency and fundamental powerlessness that every man and woman, in order to be a human being, is forced into repeated attempts to ascend from their innate ignorance towards wisdom, an effort that can only be beneficial and productive when it is as a result of a love of knowing. Or, put differently, when it comes from an outlook on life that can be described unequivocally as philosophy, a probing attitude arising from the human need to understand and express itself. It can thus be seen how this vital attitude underlying philosophical activity comes to symbolise and essencialize its educational and autodidactic function since, due to its methodological stance, philosophy insists on the absolute requirement to always go above and beyond the mere accumulation and superimposing of specialised, partial or disjointed information, like that provided by each of the individual sciences. In other words, it advocates, as its most defining feature, the need to arrive at a meaning that somehow includes the interrelationships between and the places that different partial and specialised knowledges should occupy in an ideal universal synthesis, something that would be neither attainable nor formulatable in a closed system, of the type of knowing that would reflect, in an achievable way, the totality of all that it is possible to know.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

This year’s Berggruen Prize for Philosophy & Culture, endowed with $1,000,000, has been awarded to Onora O’Neill, Baroness O’Neill of Bengarve. In addition to her teaching work at Columbia and Cambridge Universities, O’Neill is a member of the House of Lords, a member of the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission, a former Chair of the British Academy, a member of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics and a member of the Human Genetics Advisory Committee. O'Neill's work has centered on the ethical and moral tradition of Kant, building on freedom governed by individual duty, where duty takes precedence over individual rights in the quest for a more moral, autonomous society. A day before she received the prize, I spoke with Onora O’Neill in the bustling lobby of her New York hotel.

Author: Elena Cué

This year’s Berggruen Prize for Philosophy & Culture, endowed with $1,000,000, has been awarded to Onora O’Neill, Baroness O’Neill of Bengarve. In addition to her teaching work at Columbia and Cambridge Universities, O’Neill is a member of the House of Lords, a member of the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission, a former Chair of the British Academy, a member of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics and a member of the Human Genetics Advisory Committee.

O'Neill's work has centered on the ethical and moral tradition of Kant, building on freedom governed by individual duty, where duty takes precedence over individual rights in the quest for a more moral, autonomous society. A day before she received the prize, I spoke with Onora O’Neill in the bustling lobby of her New York hotel.

I would like to start by talking about the significance of the Berggruen Philosophy Prize you have just been awarded.

There have not been big prizes in the humanities and social sciences. I think the prize reflects the foundation’s leadership role in the realization that nowadays to say science is science and nothing else is needed is an obsolete statement. Take a topic like the ethics of data use, a very hot topic today; you cannot approach it merely on the basis of having the best computer scientists and technologies. We also have to take into account ethics, politics, what can and should be regulated. My experience is that Berggruen are absolutely up there with this movement who think we must take the normative, that is the ethical and political questions, and the legal questions just as seriously as we take the scientific questions.

What is it about Kant that makes him such a key reference for you?

In the twentieth century, particularly since the 1930’s, currents of thought such as logical positivism claimed that ethics, together with metaphysics, religion or aesthetics, were literally meaningless. They consist of a mere set of statements that cannot be justified. This way of thinking spread to many universities, from Argentina to Canada, to Australia, USA and the United Kingdom. There was a public response to that nihilism, the Human Rights Movement, The Universal Declaration in 1948 and the European Convention in 1950. The institutions responsible for the fulfillment of these rights were created. The issue was that this impulse to restore an account of justice had abandoned ethics. It was thought that ethics are personal, subjective. Some spoke of personal values, chosen by each person, which in turn created a need for a public debate on common ethical criteria. That is where Kant can provide his arguments. My questions were “Does he have the arguments?” and “Are they good?” That is what I have spent all these years trying to work out. Because Kant does not think that the individuals who act are isolated, but that there are common reasons that a plurality of people can adopt.

Yes, but it is difficult to follow Kant ethics.

Indeed. If I want to have a reason that can become a reason for everybody, for example, an ethical claim, a political claim or a claim about justice, I have to make sure what I give as the reason can be acceptable for everyone. They do not necessarily all have to agree with it, but they all have to be able to understand it as a reasonable way of acting. That to me is the way in which Kant is interesting.

As you well said, trust is one of the foundations of society. What do you believe to be the reason we have reached such a general widespread lack of trust today?

The empirical evidence for the lack of trust is much worse than people think. When we actually look at the polls, we find variations in different countries, but the polling evidence in the UK, for example, shows trust in certain people, such as politicians and journalists, was very low 25 years ago and remains low to this day.

What is your opinion on the lack of respect for the deontological codes in some public institutions?

In the UK people continue to trust in professionals such as judges and nurses. But it is true that some parts of the media behave very badly. I was astonished by the New York Times these past few days and their campaign against President Trump, perhaps with good reasons but what a campaign nonetheless. In regards to trust in general, we have to talk about trustworthiness instead, because we only trust people or institutions that are trustworthy. If they are not, we mistrust them.

Is this a legal problem or a moral problem?

I think it is a mistake to emphasize rights so much without integrating them with duties. The heroes and saints of the past thought about what they ought to do, not what they ought to get. Because what we ought to do is a basic question. For example, in World War I there was emphasis on patriotic duty, the idea of duty to serve king and country. Then when the war proved to be so terrible and disastrous, people turned against patriotic duty. However, duty should not be something related to subjective and personal values. We have to share values in order to live in a society and we need a certain explanation of why these values can be universal.

On the basis that you cannot be a moral individual unless you are free, how do you perceive freedom?

We should not fall for the misconception of freedom and autonomy. Human freedom can be used for moral purposes or not. But it is used for moral purposes only when in action we adopt principles that are valid for everyone. Kant never talked about autonomous persons, because it is not the person that is autonomous, it is the principle. If autonomy were to correspond to the person, moral acts would only be individuals’ arbitrary decisions, as advocated by existentialism. Certainly, I can use my freedom to adopt morally important principles such as not enslaving people or I can use it to coerce other people when it suits me.

Yes, the use of it as a medium and not as an end is frequent...

We live in a world where people are using the metric of consumer benefit for everything, even for information and communication, or in the use of social media to send messages and content to certain audiences and not others, depending on what suits them.

What do you think about the use of lies in the rise of false news on social media?

Not deceiving is one of the fundamental duties. When I think about technology, I wonder whether we will have democracy in 20 years because if we cannot find ways to solve this problem, we will not. People are receiving messages and content which is distributed by robots, not by other human beings, let alone by other fellow citizens. It is frightening.

Internet is a problem for us because we can’t keep up with all the changes and create appropriate legislation.

Even if we were to regulate the part of the internet most people access, it would be very difficult do so. Firstly, because of the multiple jurisdictions and secondly, because it is technically very hard to demand that social media websites and internet service providers operate as publishers. If the information is posted with a proper ID, then the individual is responsible for the content, but if it is anonymous, the internet service provider would have to assume responsibility. We are living in dangerous times. The misuse of the public channels of communication is so polluting and so powerful that it undercuts the basis of proper democratic politics. Perhaps we will be pushed to do what the Chinese have done and use censorship.

Society has progressed astoundingly yet it does not seem like this progress is making people happier. Depression is the most widespread mental illness and in Spain, for instance, suicide is the main cause of unnatural death each year.

It is extremely frightening and it is very hard to know what is actually happening. Each tragedy is an individual one, but it is not uncommon for people to feel that nobody loves them, that everybody hates them and that they are worthless. Sometimes, within schools children gang up on one particular child. We read stories about parents having to move their children to a different school. It is crucial to keep good communication with one’s child because once they hide away it becomes an enormous problem. My son and his wife, for instance, make sure their son has a great deal of sports, music and activities at a school. When I was young, I didn't think that was so important. Now, it is proven that if a school organizes sports, not just for the sporting elite but for all children, it is demonstrably much better. It is the same case with all other activities and social competitions.

There is a great distrust amongst people in the way biotechnological advances in food and medicine affect health. In which ways are bioethics committees useful?

One of the most important things is to try to teach people from an early stage of life to look for the evidence and respect it. We should also teach our children to distinguish those who deceive people. We had a problem in the UK with the MMR vaccination. A tiny group led by doctor Andrew Wakefield claimed that the vaccination caused autism upon which a large number of parents decided not to vaccinate their children. It was only good fortune that we did not have a major measles epidemic as it is a killer disease that can seriously damage children. The doctor has since been forbidden to practice medicine in the UK because he was using scientifically disreputable evidence as he chose his examples from children who already had autism. Meanwhile, there were about a thousand studies funded out of public money in order to see if there was any truth in his claims. It was statistical incompetence, a malicious activity that led to this and we have had other similar examples. Thus, we have to learn how to use evidence. We have now got another charity called “Evidence matters”, currently spreading to other countries, which is trying to teach people to be responsible about using evidence. What is the evidence? Where did this evidence come from? Is it good evidence? Is there a conflict of interest with the people who are publishing this evidence? Another example is the term “natural remedy”. What do people mean by “natural”? Chemicals are natural. People don’t want any chemicals in their food but even if plants are grown without any fertilizers they would still have a certain chemical makeup.

To conclude, I would like to know your opinion on whether climate change is also an ethical problem.

Yes, of course it is. If climate change is happening in a way that is anthropogenic, meaning man-made, then we can do something about it. What one has to do is try to read the evidence and see to what extent it is anthropogenic. I think the consensus is that it is, in part, man-made but of course, there are other sources of climate change but the evidence amounts.

Onora O'Neill. photo: Elena Cué

Onora O'Neill: What we don't understand about trust

- Details

- Written by Marta Sánchez

At the tender age of 10, a Japanese girl called Yayoi Kusama encountered the worlds of colour, sculpture and the modelling arts for the very first time. Enamoured ever since with polka dots, she began creating works of art in which fantasy and reality coexisted in settings where nothing was what it seemed: portraits of her mother obliterated by dots, for instance. These were works intended to reflect the disturbing hallucinations that her own mind was producing. They were the solution Kusama came up with to counteract the effects of her mental disorder. She simply painted what she saw. That same little girl, Yayoi Kusama, is still alive and well in her Infinite Rooms, in those ever-present polka dots and in those flowers on the borderline between heaven and hell.

At the tender age of 10, a Japanese girl called Yayoi Kusama encountered the worlds of colour, sculpture and the modelling arts for the very first time. Enamoured ever since with polka dots, she began creating works of art in which fantasy and reality coexisted in settings where nothing was what it seemed: portraits of her mother obliterated by dots, for instance. These were works intended to reflect the disturbing hallucinations that her own mind was producing. They were the solution Kusama came up with to counteract the effects of her mental disorder. She simply painted what she saw.

That same little girl, Yayoi Kusama, is still alive and well in her Infinite Rooms, in those ever-present polka dots and in those flowers on the borderline between heaven and hell. The artistic world of one of our most fascinating contemporary artists has its origin in the nightmares that have plagued her all her life. But as she matured into adulthood, she found the means by which to portray and display them beautifully to an adoring audience.

Yayoi Kusama at work. Photo: Vagner Carvalheiro

"My art is an expression of my life, particularly my mental illness." Yayoi Kusama

Born in Matsumoto (Japan) in 1929, her formative years were played out in a misogynistic society where women had little or no say and even less so in the complex field of the arts. In 1957, at the age of 28, she moved to New York to seek out a new way to express the artistic maelstrom that nestled in her mind and spirit. Neither the overwhelmingly robust American artistic world nor its male bias prevented her from becoming one of the most 'bubbly', innovative and active art creators of her time (and the times that would follow). In the form of installations, "happenings", oversize canvasses and performances, the work of Yayoi Kusama since then has displayed a diversity and an anxious curiosity that knows no barriers and no bounds.

New York (1957-1973)

All the eternal love I have for the pumpkins (2016) – Dallas Museum of Art

In New York, she rubs shoulders with artists of renown such as Andy Warhol and Donald Judd. She becomes part of the Pop Art explosion and the unfettered creativity of the '60s and '70s with its hugely 'influencing' installations of light, colour and curves. This is also the time of her "soft sculptures", montages of colourfully-dotted, stuffed or quilted fabrics that reveal her deep-seated fear (as she herself attested) of sexuality and penetration.

By the end of the '60s, a powerful socio-cultural movement dominating the whole American art scene becomes just too much for Kusama's spirit and wellbeing. She abandons it in favour of instead creating artworks as 'happenings', anti-war demonstrations and fashion. She also begins to make films, somewhere in between cinematography, self-portraiture and art, amongst which "Kusama's Self-Obliteration" (1967) stands out. The film won numerous awards and was a giant step towards worldwide recognition for an artist as innovative as she is fascinating.

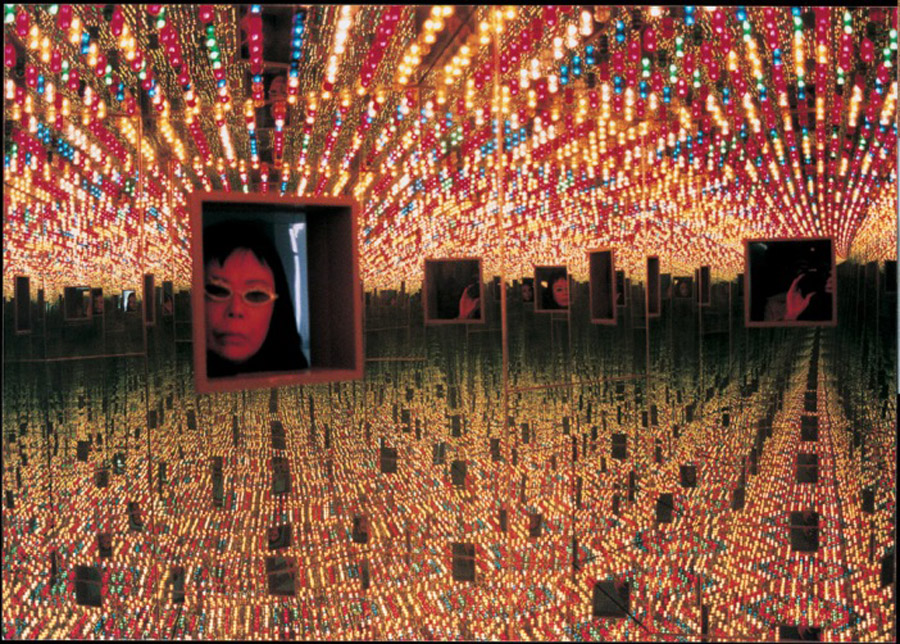

Infinity Mirrored Room – Love Forever 1996. Photo: Le Consortium, Dijon © André Morin and © Yayoi Kusama . Tate Modern, London

1973 is the year of Kusama's return to her native Japan. Her talent then truly reveals itself in all its multiple facets: from the already established plastic arts to the newly discovered literary ones. In 1983, her novel "The Hustler's Grotto of Christopher Street" wins the 10th Yasei Jidai Literary Award for First-Time Authors. The '80s see her first major exhibitions worldwide, including the Museum of Fine Arts in Calais (France), as well as New York and London. These exhibits culminate in her presence at the 1993 Venice Biennale where "Narcissus Garden" (heavily influenced and promoted by the artist Lucio Fontana) spoke to the spectator of the self-proclaimed and lifelong history of narcissism of its creator using as language her passion for flowers, mirrors and infinite, spherical shapes.

Venice Biennale. Narcissus Garden.

Yayoi Kusama in her Narcissus Garden installation, created for the 1993 Venice Biennale. Photo © Khan Academy

Although Kusama was not officially invited to exhibit, the moral and financial support afforded her by Lucio Fontana (as well as permission from the chairman of the Biennale Committee himself) meant she could stage her installation on the lawn outside the Italian Pavilion. It consisted of 1500 mirrored globes the size of crystal balls, tightly arranged to reflect only the viewer's image. Kusama placed two signs beside it: “Narcissus Garden, Kusama” and “Your Narcissium (sic) For Sale”. Wearing a gold kimono with silver sash, she sold off the mirror balls to passers-by for a dollar a piece, and each was accompanied by a flyer with flattering comments about her work. In this way, the work revealed itself to be a steely criticism of the commercialisation of art and its status as merchandise. After this, Kusama began further work on the creation of outdoor installations and sculptures.

Yayoi Kusama with recent works, Hirshorn Museum, 2016. Photo: Tomoaki Makino. Courtesy of the artist © Yayoi Kusama.

Now a world-renowned artist whose work has been recreated and exhibited internationally in the most prestigious museums and galleries, Yayoi Kusama currently lives in a private mental health facility of her own free will. She continues to work from her nearby studio and continues to dialogue with her old nightmares, the primal origin of her ever-restless and always dynamic work. Then, in September 2017, and as a fitting culmination to her career, The Kusama Museum (Tokyo) opened its doors and its five floors entirely dedicated to the oeuvre of this fascinating creator.

{youtube}rRZR3nsiIeA|900|506{/youtube}

Yayoi Kusama talks about her life and her work in this feature from Tate Youtube channel

A quirky, troubled, coherent oeuvre

If anything were to characterise the work of Kusama, it would undoubtedly be its intensity. This prolific and innovative artist could almost be said to imbue her creations with 'suffering'. Since her very first pieces, when a kind of mental hallucination was already both palpable and inseparable from the aesthetic, Kusama's works have captured the spectator and propelled them into a stream of passions.

Accumulation Sculptures. Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid Museo Reina Sofía

Accumulation Sculptures

In addition to the celebrated New York performances and "happenings" of the 60s and 70s, Kusama was at the same time creating her famous Accumulation Sculptures in which she abandoned paint as her only medium, instead merging it with three-dimensional shapes. Titled “Soft Sculptures”, they had clear phallic and sexual overtones that became emblematic of her work.

Infinity Mirrored Room – Phalli's Field (1965), Hirshorn Museum. Photo © Yayoi Kusama.

Infinity Mirrored Rooms. But if anything about the artist's work still incites passion (and one has only to remember the Spring 2017 exhibition at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington that broke all-time visitor records), it is her Infinity Mirrored Rooms. Kusama began work on this series in the 60s, a series made up of different rooms, each with floor-to-ceiling mirrored walls, shapes and lights creating an ambience intended to transmit certain sensations and feelings. They were places of peace but also of anxiety. Of colour but also austerity. Of welcome and of terror. And this because all of the sensations that form part of Kusama's life become ours, too, as we literally enter into her works.

Yayoi Kusama, a legend in contemporary art, is still today painting the stuff of her dreams and, of course, her nightmares: as awful, as awesome and as fascinating as all of ours.

Further reading:

- Yayoi Kusama. Infinity Mirrors

- Infinity Net: The Autobiography of Yayoi Kusama

- Yayoi Kusama. Revised And Expanded Edition

- Women In Art. 50 Fearless Creatives Who Inspired the World

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Yayoi Kusama: Biography, Works and Exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

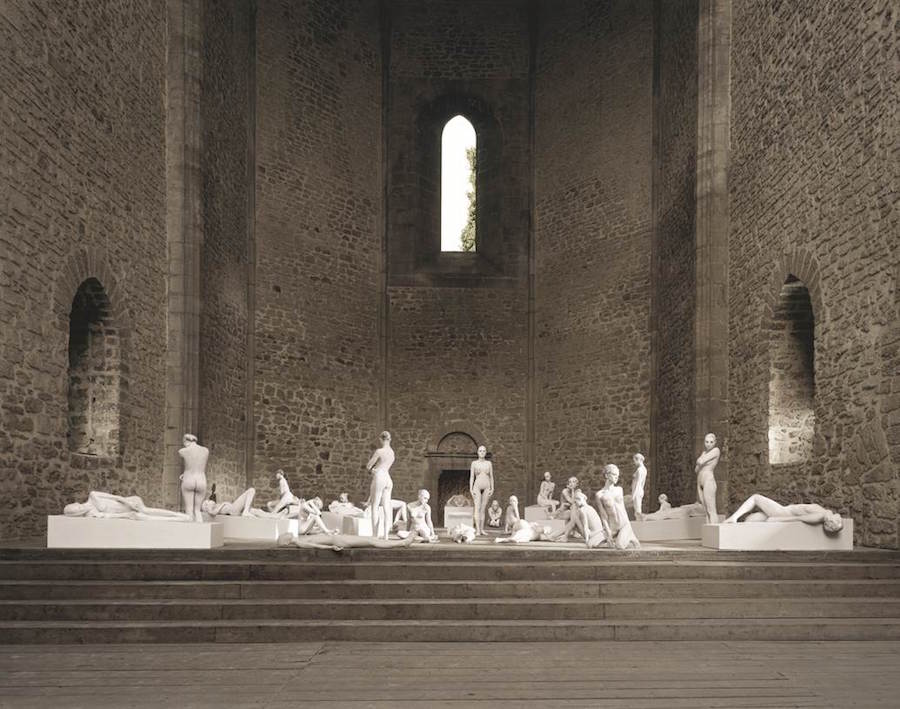

The new space created for large art exhibitions Pio Pico in Los Angeles, founded by Federico Spadoni, opens its doors to the public for the first time and until March, will host an exhibition based on the notions of classical sculpture by the multidisciplinary artist Vanessa Beecroft (Genoa, 1969). She is internationally known for her iconic conceptual performances which often include historical, political or social references associated with the place where they are made. Subsequently filmed and photographed, these solemn groups of hieratic naked or half-naked women coexist in a form of sociable unsociability. Beecroft suffered from eating disorders since the age of 12. This obsession with food led her to write a diary of all the foods she consumed for ten years: «The Book of food».

Author: Elena Cué

Portrait of Vanessa Beecroft 2015 polaroid. Pico Studio, Los Angeles photograhed by © Federico Spadoni, 2017.

The new space created for large art exhibitions Pio Pico in Los Angeles, founded by Federico Spadoni, opens its doors to the public for the first time and until March, will host an exhibition based on the notions of classical sculpture by the multidisciplinary artist Vanessa Beecroft (Genoa, 1969). She is internationally known for her iconic conceptual performances which often include historical, political or social references associated with the place where they are made. Subsequently filmed and photographed, these solemn groups of hieratic naked or half-naked women coexist in a form of sociable unsociability.

Beecroft suffered from eating disorders since the age of 12. This obsession with food led her to write a diary of all the foods she consumed for ten years: «The Book of food». This diary was the center of her first performance in Milan in 1993 where she made herself known to the world of art. The presentation also included the «living sculptures» of 30 women with eating disorders, wearing their own clothes and moving through the space where the demonstration took place.

It could look like the other side of the mirror...What is autobiographical about your performances?

The emotional impact, narrative and certain traits of women. The relationship with the public which is confrontational or, as Dave Hickey defines it, there is a separation, a use, in addition to governing rules that do not apply to us.

You said “The day I decided to use The Book of Food as art was the day I stopped”. Does art heal?

Art does not heal. It transforms aspects of life into an iconic and permanent form. It translates pain into something universal that transcends life in its immediacy.

vb52.002.nt. Castello di Rivoli, Turin, Italy, 2003. © 2017 Vanessa Beecroft

As an Italian, you will have grown up surrounded by the history of art, in a natural way. Which sources provide the artistic inspiration for the aesthetics of your performances and photographs?

In Italy, as a child, culture became a landscape and an immediate background. Instead of a flower you’d see a Laurana head or a Pollaiolo painting. You were raised not seeing the difference between a girl, a Piero della Francesca portrait, and a random religious painting on a fresco on your walk to school. The sources of my inspiration became the paintings and sculptures of the 15th and 17th century, and the architecture of any era.

What type of beauty does your art convey?

A beauty that is equally particular and universal, that tends to be idealized but comes from the street. A beauty connected to the human form, the female form in its artistic, cultural and social representation. I use beauty to relay other hidden messages.

Vanessa Beecroft. vb62.018.nt, 2008, Spasimo, Palermo, Italy. Photo Nic Tenwiggenhorn, Courtesy of the artist

That mystery makes your work open to different interpretations which creates a lot of controversy. How do you perceive the women you represent? Why collective and not individual?

The women are often there as a physical equivalent of what I am going through. She is not alone because she is speaking for a group, for more than one person and because a group is stronger and more convincing than an individual. The women have similar aspects but there are also differences between them. They are organized in a hierarchical formation in which there are privileges and unbalance, symmetries and color-schemes.

You have been defined as a feminist. What does feminism mean to you?

The fight of women to survive in a society built by men, mostly white men. Feminism today cannot be the same as it was in the past. The new feminism is stronger because women accept their womanhood, their body and their maternal power, while before they were forced to deny their identity as a female since it tied them to so many bad memories.

Vanessa Beecroft. vb48.006.dr, 2001, Palazzo Ducale, Genoa, Italy. Photo Dusan Reljin, Courtesy of the artist

You have collaborated with the rapper and designer Kanye West over ten times. Your presentation of his new clothing line Yeezy Season 3 and his album The Life of Pablo in Madison Square Garden became the most-viewed performance art in history, with over 20 million viewers. How has this collaboration influenced you?

We dealt with a larger audience than the one of the art world and a general audience that had to perceive a message in a more direct way. The social impact was greater and the artistic value could be less subtle. Kanye’s work intended to go beyond its artistic value, to the point it affected his own life. I was influenced on a human level and after the experience, I longed to be in the artist’s studio.

What is it about your relationship with Africans that makes you feel autobiographical when you work together?

I only work on matters I can identify with.

Installation view, untitled (tableau) 2017 pio pico, Los Angeles courtesy of the artist © Vanessa Beecroft

Your iconographic framework has always involved the human figure, almost exclusively the female one. What is the meaning of the body as an instrument in your art?

It’s the most direct way of talking about humankind, in this instance of a woman, my own experience, and a shortcut to use forms, lines and colors on the subject closer to me: myself. However, I do not consider the body to be something physical. The body is there to express intellectual thoughts, emotions and formal solutions.

Your new sculptural work, for Pio Pico’s inaugural exhibition in Los Angeles, is inspired by notions of classical sculpture. What can you tell us about this series?

The sculptures have been molded by hand in clay, from the source material I could find in LA. I molded them without a plan just as when I sketch. Then they were fired in various colors’ clay. Some survived the kiln, but many didn’t. I assembled them in a performance-like group using materials like wood and beeswax as support and as a way to add a bit of coloring. There is also a large mural which represents the body imprint of a group of women, mostly African-American. The imprint was made on clay and a positive in plaster is exhibited. I wanted to realize a negative in ceramic but it was too difficult to achieve an optimal result for this exhibition.

There are also bodies…

Yes, classically inspired large sculptures of clay. One of them has exploded tonight. The other one is put together roughly by beams of wood. I don’t think of sculpture as a category. I think of all disciplines as a way to relay my story.

Untitled (gray body), 2017, digital c-print with diasec © Vanessa Beecroft, 2017