- Details

- Written by Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca

|

Contributor: Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca, |

|

She got out of her car, knees together, showing off her elegant high-heel shoes, her skirt cut and her printed silk blouse with a cleavage that left the smooth skin of her neck in full view. This image of Isabelle merged with the other images that were still in my memory, jumping around and crashing into one another over and over again, obstructing the truth and pulling me towards that world of memories previously alive, idealized or simply made up. It was getting dark outside and I was about to reach Sils Maria, in the Swiss High Engadin, to take part in a congress on Nietzschean philosophy, together with a high-level international group of experts.

Her weightless, ethereal hair in the wind and her big blue eyes were the hallmarks of this free and modern woman, someone who moves with independence and who knows how to get the most out of life. At the same time, though, she enjoyed an elevated philosophical and intellectual reputation which inspired admiration in students and teachers alike. It’s impossible to reach the levels of understanding of the difficult topics she has written about without some kind of rigorous asceticism, and her academic career was a testament to her courage and self-discipline. Nonetheless, and in contrast to this, she was also well-known for her desire for fun, for her girl-about-town attitude, and for her ability to mix smoothly with the shadows of the night where, together with all the luxury and glamour, one also finds touches of the banal, the frivolous and, yes, the obscure.

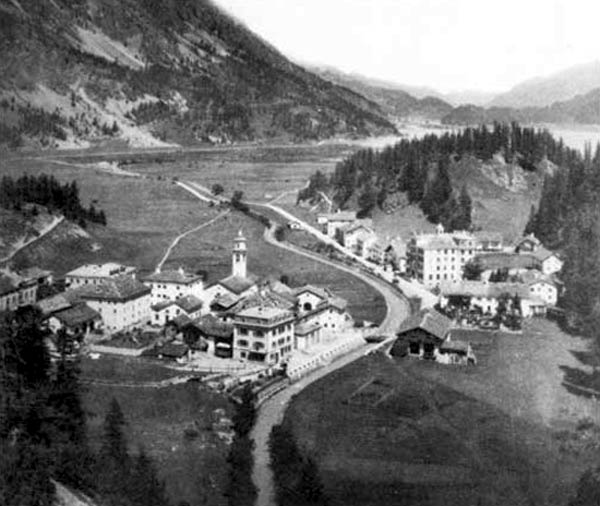

Although this wasn’t the first time she was visiting this incredible location in the Swiss Alps, the landscape of the valley and the sublime mountains made an impression on her once again, to the point where she was naming the peaks to me one by one. On the Northern side, Lagrev and Gravasalna, and to the South, Rosatsch, Corvatsch and Chapütschin. And then of course the lakes: the Campfer, Silvaplana and the Sils, its waters shifting between sapphire blue and turquoise. The colours varied between the light green of the meadows at the base, to the darker green of the great woody masses on the sides of the valley, to the grey of the peaks and the white at the very top, the colours morphing from one to another with magical fluidity: within an hour they would go from the joy of the sunny brightness to the severity of the greyish fog and mist. Among that deep silence, one had the impression of witnessing the birth of the world, since neither the grass nor the earth nor the water seemed to have grown old at all.

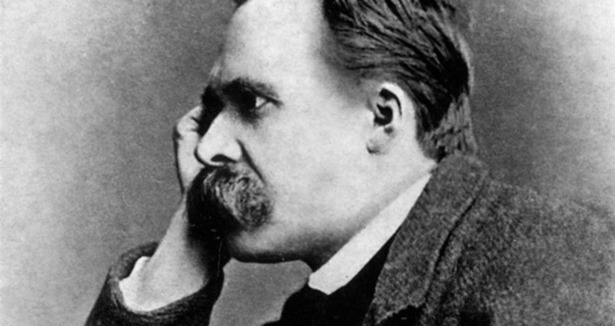

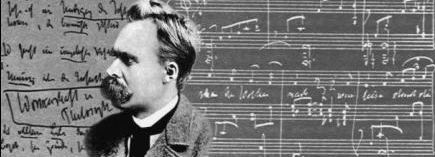

Isabelle remembered that during the summers that Nietzsche spent there, between 1881 and 1888, he lived in a rustic lodging that was part of a small group of houses on the valley-side, with balconies full of flowers. After some time, the original village had become a place of luxury for affluent holiday-makers. “Nietzsche”, she would tell me, “would come here to think and to write. He would work in the mornings, take a stroll during the day, and return in the evening with his notebooks full of notes, only to resume working after dinner until well into the night. According to his journals, the strolls he most enjoyed among the many that he took (through the woods, along the shores of the lakes, in the mountains, etc.) were the ones that took him up towards the lookout point, from where one can contemplate the solitary Surlej, lying among the meadows; or even when he went up until he reached the throat of the Fex from where, to the right of Platta, it is possible to view the entire amphitheatre of peaks. How about we go on these strolls ourselves today?”

The congress’ first talk was given by a veteran Italian professor who read out the content of a letter by Nietzsche to his friend Peter Gast from August 1881, in which he wrote, “Here in Sils Maria the most unexpected thoughts strike me. My dear friend! Sometimes I get this strange feeling that I’m one of these machines that explodes. The depth of my emotions makes me shiver and laugh. Sometimes I can’t leave my bedroom simply because my eyes are all red. Why are they so red? Because the previous day, while I was strolling, I had cried too much, not with sadness but with joy. I was singing, I was talking nonsense, I felt full of life again, a feeling I now treasure in myself as others seem to lack it”. It was obvious, the speaker was adding, that Nietzsche needed solitude. He would arrive here full of work projects, only to find his trunks full of books sent to him by his loyal friend Overbeck from Basilea. Here he read Spinoza,and was surprised by the proximity he felt towards him; he dabbled in mechanics, political economy, cosmology, biology and psychology. A great transformation was growing inside of him, and for it to bear fruits he vitally needed solitude. He was fond of saying that he came here to “disappear forever” (der auf ewig Abhandengekommene). But the most important reason was, in fact, that in Sils Maria he could take long strolls and seek out inspiration, because to him — and so he mentions explicitly on more than occasion — his best ideas would come to him when he was climbing the mountain.

Another speaker referred to the inspiration that Nietzsche confessed to have had in Sils Maria that led to his more decisive thought, his most enigmatic and difficult. While taking a walk near the huge monolithic block of the Surlej, a vision came to him, making him shiver and write in his journal: “This was written at 6,000 feet above the rest of men, and in the present time.” What had he seen in this ecstasy, and what was this note hiding?”, the speaker was wondering. From what he told us later, in Ecce Homo, in this vision that had divinely exalted his soul, he thought that he had suddenly grasped the law of the worlds, their eternal return, in a kind of Heraclitean or Pythagorean reminiscence. A very old thought, suddenly uncovered from its oldest most forgotten recesses, just glimpsed in a kind of trance far beyond our daily experiences and the limits of our senses. Some have been quick to point out, “This is proof of the beginning of his madness”. Nonetheless, ended the professor, Nietzsche converted this intuition into a liberating thought with the power to transform us all into superhuman beings.

By the time it was Isabelle’s turn to speak, there was already much anticipation in the room. She began somewhat abruptly, raising her head rhythmically throughout her talk, and smiling indifferently at the end of each small pause: “Totalitarianism,” she began, “is the most successful figure of the solemnity of our faith in being… We could say that it is the exacerbation of the profoundly human tendency to compensate for the wants of being with an overdose of being. We don’t just see this in totalitarianism, however. The fullness of being is affirmed and reaffirmed in all official debates on politics, art, culture, religion, etc., also in our democratic societies. We need an idealized, idealist world, perhaps deified and adorned by a native happiness. And for this reason, those who have ironically insisted in the system’s discordant aspects have been expelled from the circle that is being closed with the same lively enthusiasm with which one attempts to exorcize the devil’s laughter. Nietzsche, lover of these avenues, inspired by these heights, suffered this exclusion, and is still being excluded to this day.”

She continued developing her argument, referring to an irrepressible fight between things and their meanings, between human beings and themselves, calling it the best definition of reality. “For this reason”, she concluded, “this fight is unleashed, and is always accompanied by the desire for lost, unrecoverable harmony, which is the desire that dominates in that construction of worlds in which the inessential takes on the appearance of the essential, and where a false harmony covers up a reality full of noise, dirt and cruelty. Only when it is transfigured in the beauty of an artistic illusion, wrapped in the dream of a myth and of Apollonian measure, can the absurd and terrible character of existence be contemplated, only then can it seduce one to live it.”

The auditorium, now more full of people than in previous talks, showed its satisfaction at the end of the conference with a resounding applause, and the other speakers made complimentary remarks and thought up various questions that Isabelle answered with brilliance and elegance.

“Take me away from here”, she whispered to me, approaching me when the next talk was about to begin. “I need a drink. It’s a matter of life and death”.

We went to a pub and she asked for a large gin and tonic with Citadelle. I complimented her on her success, although I noted that she wasn’t really enjoying it. She seemed indifferent, quickly changed the subject and began pondering the virtues of the botrytis cinerea, a bitter-tasting fungus used to sweeten Santernes wines. Then she added that what she really fancied for dinner were crépinettes scented with Piedmont truffle and ox carpaccio washed down with a good Burgundy or Moselle. And to end the evening tasting a good Krug Millésimé in an ice-cold glass while we gazed at the stars’ reflections on the surface of the lake. “Oh darling!, there’s no place like Paris to live life to the full, there’s no place like Paris to dream of a full life”.

The waiter returned and served her another round, this time pouring blue Bombay Sapphire in a wide glass full of crushed ice, while I stood there looking at her, intrigued by her mystery, an oracle of the occult that I attempted to decipher to sense what it was that she was hiding behind her face, behind her words.

“In love with Nietzsche, perhaps?”, I asked her.

“It’s difficult to be in love and be productive at the same time”, she answered. Her gaze returned towards an undetermined place, she became quiet and after a pause she added:

“To stand out professionally is difficult. The best thing to do to get attention is to say or do extravagant things.”

The only thing separating us was the glass with ice, which was slowly melting and sticking to the slice of lemon. With a sweet, serene gesture and a look from within, she continued: “The best lovers, if they really are in love, are in a rush to end their torment, and they do everything they can to liberate themselves from it. In order for the relationship to last, one should never swear to be in love. What love does not end up telling itself the little totalitarian story of its harmony, rebuilding a past in line with its aspirations, from which are excluded all doubts, all emptiness, all disappointments and infidelities? I think that, because of this, love — and not knowledge — is where human beings sign their most solemn pact with being. A pact which must be inseparable from parody, because there are no loves in which there is no adaptation to being, in which the misunderstood is not the most important person (the illusion of a full alignment with the other, right there with incommunication, tension and discordance), in which the only existing link is not that of jealousy of compassion, and in which the very idea of love is not continually betrayed by its figures. What I like about Nietzsche’s criticism is that it is still as hurtful and intolerable for many because it unmasks the mystifiers who manipulate and decorate this “reality” with fictions and absolute and totalitarian masks. These impostors don’t care about the truth that all authentic faiths always go hand in hand with doubt, and that the important things in life, like love, are never protected from the erosion of expiration, mistreated because of what we do to them.”

On Saturday, at the end of the congress, we spent a day out to Surlej. The birds flew across the sky at the start of the day while we began our trek up the mountainside. The daylight had a delicate, imperious quality to it, while the lake reflected in its stillness the blue of the sky, a few grey butts that crossed it and the vegetation of its shores. The beauty of the place gave the morning a sort of false euphoria that imposed itself on my imagination, as I remembered the words and conversations with Isabelle. “What beauty!”, she exclaimed, placing the back of her hand on her eyes to cover herself from the sun. Suddenly the sky began to darken and the day started turning into a strange night, bathed in a livid light that seemed to grow from the surface of the lake. An inverted light that was being projected back onto the black butts.

“What inexplicable means is this, do you think”, she said to me, “that converts white into black, the interesting into boring, the risible into essential or the fascinating into fearful? It escapes us. Meaning occupies, and encroaches on, the space of the absurd, the anxious confirmation of nothingness is soon alleviated by the firm weight of what is. This is our most common experience. But then, doubt and skepticism must always remain like the hidden face of our faith and of our original assent to meaning. Nothingness is not the absence of being, but its double interior, its inseparable opposite.”

Once we arrived at the top, the air mixed the fresh outpours of rain with the smells of the woods and the breath of the grass, its humidity quickly evaporating under the sun. From that height, the torsos of the mountains, as if rising up from nothingness, formed delicate, fantastic, imaginary scenes. Small pockets of vegetation floated on the blue mirror of a lake, slightly pushed by the wind, while the trajectory of my butts, reflected on the surface, created the illusion of a world which seems to be endlessly sliding by, but which, in reality, always stays the same, motionless.

- Details

- Written by Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca

|

Contributor: Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca, |

|

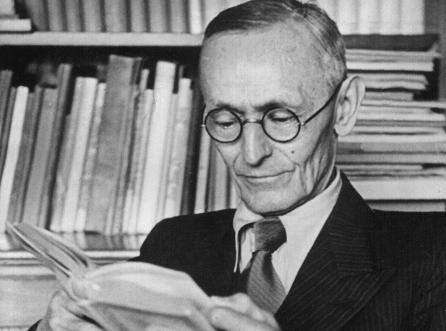

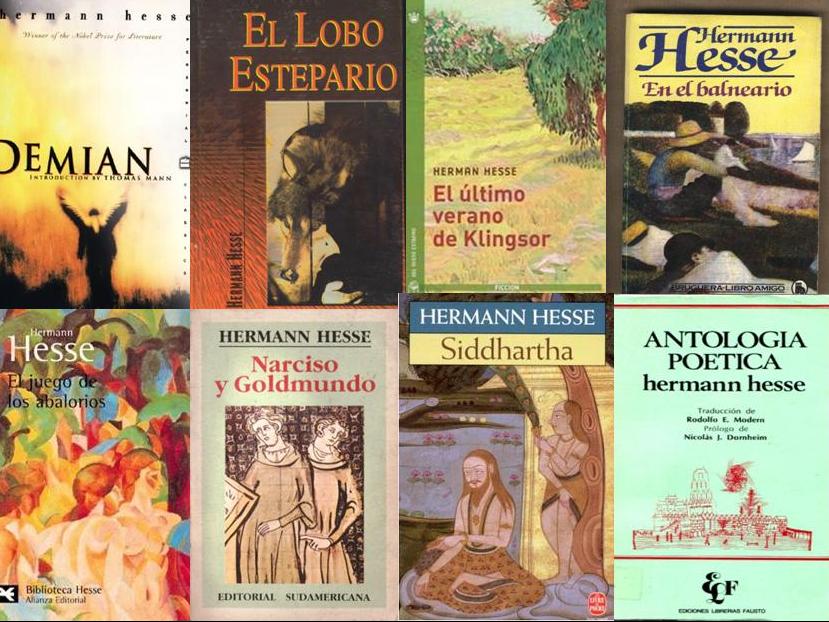

It was Hermann Hesse, together with a few other authors, who showed me from a very early age that literature is the refinement and perfectioning of life that is achieved through the kind of internalization often found in fine art. Internalizing does not mean reducing narratable external events to their minimum; rather, it means combining a series of events with a specific narrative message, within that apparent stopping of time that, again, we often encounter in fine art.

Hesse’s novels and short stories do not simply reconstruct events; they explore a wide range of existential and spiritual meanings through allegorical mediations and myths.

Many of his works show us entire new worlds and periods of time that seem to have never existed. His anti-heroes are symbols of misfortune, thrown out and left to rot in the ignominy of history from where they linger and stare back at us until our eyes hurt. It seems like Hesse wants to escape from the metaphysical-rhetorical optimism of classic European and Western humanism in order to defend the insoluble, inexorable union between pessimism and humanity. The way I see it, this is precisely what many of his allegories try to express — they are aimed at the source of a kind of happiness that is not quite of this world, but only because to achieve it requires a kind of inner transformation that intensifies the experience of the spirit. This is one way of extracting from Hesse’s books the spiritual richness within them, and of interpreting the self-reflexive, expressive mediations of his writings as new ways of understanding and practicing art.

It’s true that, today, many of Hesse’s novels feel rather distanced from our modern sensibilities: they almost feel like symbols whose role is to “represent”, at least in the Schopenhauerian sense of the word. The poetic distance of novels such as Demian, Beneath the Wheel, Narcissus and Goldmund, Rosshalde, Steppenwolf or Siddharta is, in fact, an ironic one, one which expresses a worthy critique of that unquestioned dogma: that there should be no pain in the world of representation.

In other words, the irony that is the anachronism of Hesse in our contemporary world is due to his positioning himself halfway between an allegorical short story about the soul of the modern European and a phenomenology of the disgraced conscience of the generic Human Being, who appeals to the highest, most seductive form of art as a parody secretly turned against itself. In this sense, detailing the exaggeration and the extremism so characteristic of Hesse’s spiritualism, this notion has a long history, because it reflects the intellectual disposition of those who grind their teeth in proud modesty while passionately seeking truth in beauty, as many philosophers and artists have done and will continue doing.

- Details

- Written by Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca

With his face resting on the window, Alessandro looked at the Starry Night who aroused in him an inexplicable craving for remote and beautiful things. The orange trees and magnolias, still blooming, gave off strong aromas at that time. In the background the dark masses of straight olive and acacia trees marked the limit of Beccarisi Villa, the luxurious Sicilian villa of his friend Giulio where they would also spend that summer. Alessandro recalled his previous visit and finding that secret hidden corner at the end of the garden near the greenhouse, where one night he heard hugs and kisses in the dark as the moonlight created the illusion of fantastic figures fluttering behind the glass between whispered sweet words, interspersed with sighs and sudden silence. As the fermentation of the fertile and burning ground, there he also experienced the mysterious sound of the eternally creative and destructive life.

|

Contributor: Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca, |

|

"Pleasure is even deeper than the pain.

The pain says: Pass!

But all joy wants eternity.

It wants deep, profound eternity! "

Nietzsche, Said by Zaratustra

With his face resting on the window, Alessandro looked at the Starry Night who aroused in him an inexplicable craving for remote and beautiful things. The orange trees and magnolias, still blooming, gave off strong aromas at that time. In the background the dark masses of straight olive and acacia trees marked the limit of Beccarisi Villa, the luxurious Sicilian villa of his friend Giulio where they would also spend that summer. Alessandro recalled his previous visit and finding that secret hidden corner at the end of the garden near the greenhouse, where one night he heard hugs and kisses in the dark as the moonlight created the illusion of fantastic figures fluttering behind the glass between whispered sweet words, interspersed with sighs and sudden silence.

As the fermentation of the fertile and burning ground, there he also experienced the mysterious sound of the eternally creative and destructive life, the grandeur and beauty of the pleasure of life that continued even when the lovers parted, his shadow touched hers as in an embrace under the deep blue sky of dawn, which began to dim the stars. The memory of that summer full of light had continued in his soul, more alive than in his tumultuous present.

"The experience of transience and incessant short living", Giulio had said at one point in the conversation over dinner. "To know that we lose ourselves as the wind does, and we flow like the water of a river. The perception of this continuous flow, when you think about it, does it not raise an inevitable resignation and anguish? Time is the instrument of death, the last structure of a lost experience. How many things there are that we will never see or know! "

It seemed he wanted add something else, but he stopped.

"What then is the continuity?” Alessandro had immediately replied, "Is there any point in the thought of eternity (Ewigkeit)? Do you think there is no place or experience where the agitation of change is calmed and we pick up what we have lost? I think it is not a mere illusion of the poet who says:

"I know one thing there isn´t. It's forgetfulness.

I know that eternity endures and burns

the precious and all I have lost

tonight, this moon and this afternoon ".

"However, what place could be that of permanence, even more, of eternity?" Alessandro continued thinking later on. "The days tend to become equal in the memory, although not all the same. And the most common life among men is that of a relentless nightmare, a stubborn routine with a dispensable story, a set time and the wait for obscurity to offer us one last dream without memory. Was Giulio right? Life is nothing but the desire of a dreamt destination longing to become real, a tale told by an idiot in which the protagonist awaits his end at any moment when everything would be about to begin. How to understand time as a mysterious cross over, in each moment, of change and eternity?

The afternoon was burning strangely in the clouds, as if behind them an ocean stirred into flames, a divine fire. Shaken by his own words and thoughts, he left the garden despite the intense heat and walked along a stretch crop towards the city. The grass between the vineyards was dotted with small flowers where above them yellow and white butterflies fluttered. The harvest in the fields was tall. Each stem was bent over the earth bearing fruit. Under the trees, sitting on the grass, a group of peasants rested a moment from the hard work of mowing and greeted him taking off their hats, as he passed by. Further, in the pool, some children were bathing across the sparkling waters, reddened by the sunset colors. They slid along rocking to the rhythm of the gentle breeze, and above the waters the shadows of palm trees also rocked, while on the other side there was a murmur of young voices and laughter. The still air was only occasionally interrupted by the lure of a bird.

"There are many things we will never know", he said to himself. "Maybe that's why it is desirable to even forget what we know, and be content with seeing the world in silence."

He continued his walk absorbed by the landscape, moving from image to image through a tenuous game of ideas and rethinking that which troubled him:

"The certainty of the end encourages seeking solace in the pure present, satisfying the intense enjoyment of the pleasures in life. Thus, the wait has been enriched by the remembrance of the idealised past, reconstructed to suit our most beautiful dreams. In its absence time goes by without thinking. The human soul does not reveal its mysteries. When you ask it, it remains silent."

Without being able to unleash this reflection, again a dull breath disturbed the peace of his rest. He had reached the shore and saw, buried in mournful resignation, the area in which daylight no longer shimmered. The sun had set and it darkened over the city. Everything became quiet and peaceful in that cramped and hot afternoon, where the first indoor lights shone while a big white moon lurked in the sky. He crossed the fishermen neighborhood and as he walked past a tavern, he heard music, songs and the sound of a big party. He entered and went to the bar while the musicians played a light rhythm and a young woman prepared to dance. Her hair glistened with perfumed oils; her body radiated party excitement and the smile of her mouth revealed sensuality of laughter and kisses.

She was dancing barefoot and entranced, as if embracing invisible bodies that no one saw, as if to kiss lips that were parted and bent over hers lustfully, as if caresses were to be spilt all over her body and she would enjoy those invisible bodies in unusual raptures of her dance. Maybe she lifted her mouth towards precious and sweet fruits, and sipped hot wine when throwing back her head and her eyes full of desire edging her head high. And so she continued moving alienated, surrendered to the irresistible power that dominated her.

When the music ended the girl stopped and stood in front of everyone. It was the most vivid expression of pleasure, a beautiful single flower that had just opened while a multitude of eyes looked drunk with wine and sin. And while Alessandro watched, he had an inspiration: Dancing! The relationship of life, whose substance is time, why not knowing what is called eternity is only understandable from the ancestral and Heraclitean ring symbol. The succession of things and worlds is nothing but a dance, the perimeter of a circumference, a wheel that rotates on its axis, a cycle that repeats forever.

"Only art instructs us about this mysterious relationship", he began to reason, "Art simulates stopping time, bringing together the gerund of living and seducing with a look of beauty. If faces go as dances, art sets our face and gives back the image of our own face. This transformation simulates the time in "eternity", and allows man to follow the old Apollonian advice: 'to know oneself'. Our face, being familiar but unknown at the same time, looks at us from the mirror and shows us all of the strangeness in ourselves. It is only prudent to go with what is shown in the mirror and its indefinite multiplication of things."

When he gleefully recounted his discovery to Giulio, he was pensive and after a moment he said:

"Do not be naive Alessandro. But what power does the art have versus the obsolescence of reality and its spectral reflection. It does not answer the philosophical question that leads irresistibly to the connection of time weaving and unravelling. The life of man is the fate of a caged lion repeating its monotonous circular paths without knowing that there are meadows and mountains outside of its path."

"Indeed, Giulio, that's how it is", I replied. But because of knowledge of such a hard fate it would be unbearable. That is why the Gods, pitiful upon us, grant us the grace of oblivion, the consolation of not knowing. What it is an unknown destination? The children´s games of freedom. The novelty fits unpredictability as well as the consequent openness and incompleteness.

The destination is frozen time, and time is a corrosion of that destination. This will, therefore be hereinafter the motto of my life: "Convert the outrage of the years in music, in a rumour, in a symbol ".

Alessandro finally felt rejoice in solitude and calm, and watched for hours and hours for the vibrant sky to clear as he was dominated by inexplicable thoughts. His eyes were intoxicated with the bright colors of the branches on which the rays of sunshine poured. Silence welcomed his dreams in the lonely twilight hours that followed then when the night slipped into his room and stood before the window lost in the shadows. The air was again filled with the intense perfume of orange blossoms and roses protruding from the garden fence, as well as mingled with the scent of jasmine and honeysuckle that climbed hugging the tree trunks.

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

|

Contributor: Maira Herrero, |

|

German historian and journalist Florian Illies’ 300-page book is a humorous, fleeting look at the main cultural events in Europe just before the Great War.

Illies’ book is neither novel nor essay — it is simply an account of the key creative and cultural happenings in those twelve months of the year and their effects on society and culture, moments before the advent of the bloody massacre that would subsequently rock the very foundations of Western thought.

It’s an attractive read for anyone interested in the artistic avant-garde, the influence of psychoanalysis on later thinking — particularly at the Frankfurt School —, the great literary works and cultural milestones of the time and the shift in perspective that was spreading across Europe, coinciding with the gradual disappearance of the existing lifestyle. Western culture found itself launched to heady new heights thanks to technological, industrial and artistic progress, only to collapse tragically not long after.

The book follows two parallel threads, on the one hand the epistolary relationship between Kafka and his beloved Felice Bauer, and on the other the turbulent relationship between Alma, Mahler’s widow, and Oskar Kokoshka, as told through his well-known painting Bride of the Wind (1913-4).

During the twelve months of 1913 we see the 20th century’s greatest creators come and go: Arnold Schönberg and Igor Stravinsky and radical new musical forms; Freud and C.G. Jung’s civil struggles; the break-up of the Der Blaue Reiter (Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Albert Bloch, Robert Delaunay) and the Die Brücke groups (E. Ludwing Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, etc.); the rawness of George Grosz’s paintings, an example of art as weapon against authority; the innovative architectural styles of Peter Behrens (who just a few years earlier was responible for the turbine hall at the AEG factory), Walter Gropius, Adolf Loos and many others who placed light and symmetry at the centre of their work.

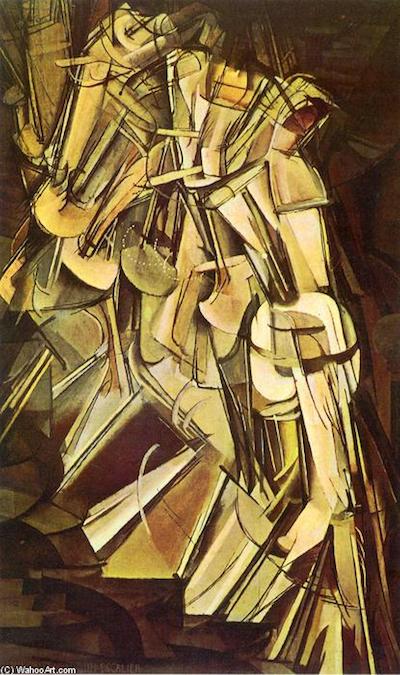

“It was as if the current art exhibition coming from Europe had fallen on us like a bomb”, reported the publication Camera Work on the exhibition running at New York’s Armory Show at the beginning of 1913. American visitors found themselves completely stunned by Marcel Duchamp’s Woman Descending Staircase (1912). In Berlin, a few months later, the legendary art gallery Sturm would host Germany’s First Autumn Salon, a collection of avant-garde works (with the notable exception of the Die Brücke painters). Gertrud Stein was the epicentre of Parisian art, her home a meeting place for established artists such as Picasso, Matisse and Braque. The collector Eduard Arnhold regularly would host regular meetings with Emil Nolde, the great Berlinese patron together with James Simon. Writers, thinkers, editors, merchants were everywhere to be seen.

Paris, Berlin, Zurich, Venice, Vienna, Munich were some of the regular haunts of the progressive class of the time. Cities were gradually transforming into large metropolises; fashion was becoming an integral part of a new kind of lifestyle.

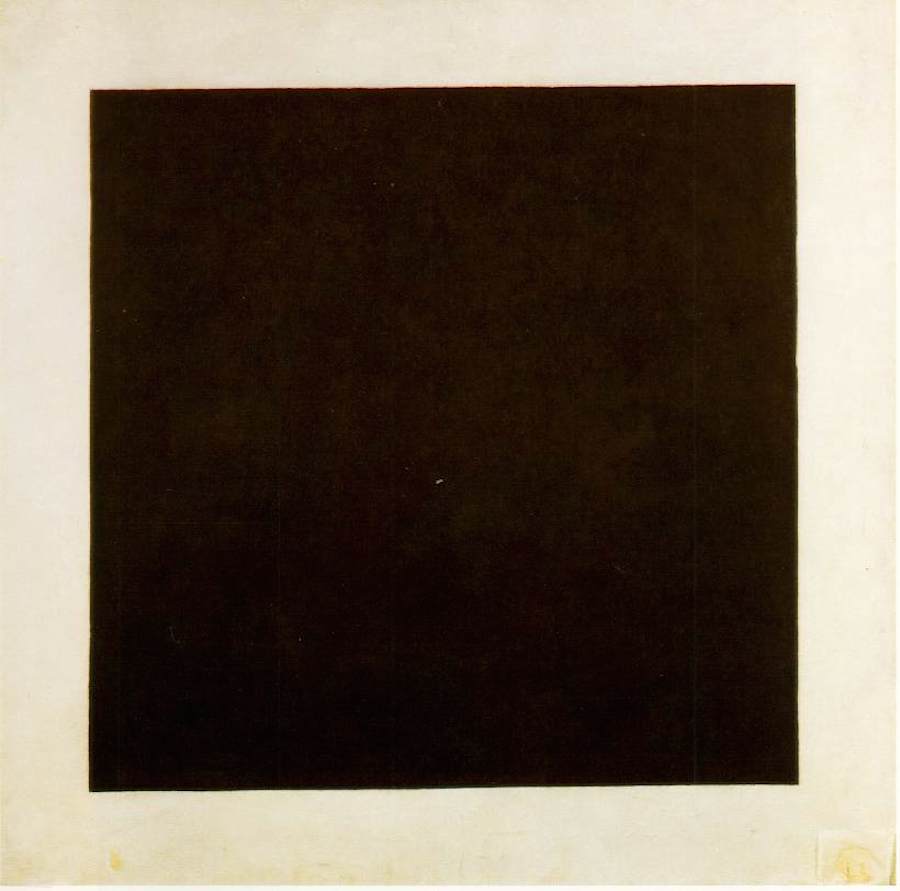

The book thankfully includes numerous comical anecdotes and stories which, although they don’t strictly belong to the year the book focuses on, appropriately adorn the tale. One could almost call 1913: The Year Before the Storm a guide to the fascinating world of exuberant creativity, finally ending with the Suprematist manifiesto and Malevich’s Black Square (1915).

Florian Illies. 1913: The Year Before the Storm. Salamandra, 2013.

- Details

- Written by Marina Valcárcel

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel.

Art Historian

|

|

Chekhov and his wife, actress Olga Knípper.

"Give me a wife who, like the moon, will not appear every day in my sky." (Chekhov)

Throughout 2013, after Alice Munro was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, it was impossible not to hear someone saying that Anton Chekhov (1860-1904) is "the father of modern literature". So a few weeks ago I decided to sit down and re-read "The Steppe", and I found myself once again with a strange, uneasy feeling inside me, as if something had remained there, deep down, undigested.

The 150-page novel is about the journey of a child over the Ukrainian steppe set around 1880. For Chekhov, the Russian soul was something dependent on the unparalleled solitude of the steppe landscape, something he wanted to describe slowly, gradually, as if through canvases, page by page, revealing themselves - a creative process one could describe as written painting.

How many painters, illustrators or film directors have been able to convey a storm as convincingly as Chekhov?

The true protagonists in the book are not people but the vivid descriptions and the landscape. Apart from these standout elements, though, it's a generally slow read with very little action.

So if nothing much happens, how do we explain the impact it has on the contemporary reader?

It's a pertinent question, particularly in an age of immediacy, information overload and expectations of complex, highly elaborate content. In the midst of recent Oscar-winning films about relationships between a man and an operating system, or the full-on anxiety of a space mission gone wrong, what can we hope to get out of a book whose opening lines describe the flight of a bustard? Why are we so impressed by the description of time passing one morning in the countryside, as if it "stretched endlessly, as if it had stopped altogether"? The author makes us excited to see how he unravels the decline of Russian society at the end of the 19th century through the actions of an old priest. "Father Jristofor had never experienced a concern so strong as to tighten his soul like a boa."

Further answers to these questions can be found by making parallels with the world of painting.

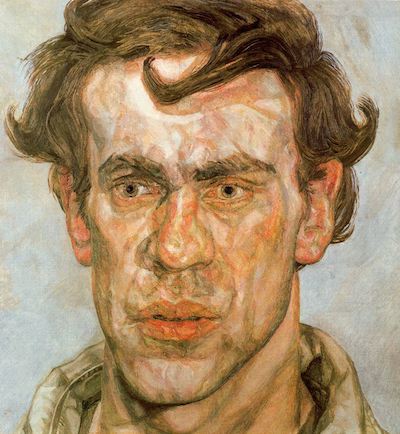

When we study Jan Van Eyck's "Man with Red Turban", for instance, we start looking at each and every strand of mink hair on the neck, we study the eye closely, and we even discover a tiny drop of blood in it - it's a similar mental slap to the one we experience when scrutinizing Freud's "Portrait of the Young Painter".

Looking more broadly, it's also similar to the "tornado effect" caused by, say, Chekhov's (or even Thoreau's) letters, or David Forster Wallace's novels.

Perhaps it's merely the fact that all these works of art come from a place of genius. They have all left us with some sort of sting in a corner of our hypothalamus, an intense, uneasy feeling that's difficult to shake off. We're predators of emotions and we recognize our catch.

- Details

- Written by Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca

|

Contributor: Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca, |

|

Art is a pleasing, entertaining, educational trick of the imagination. In and of itself, a piece of art, a creation, is nothing more than the physical outcome of life’s primal creative energy. Ultimately, creating art and living life are one and the same activity, life being the continuous creation of a world of appearances being continually produced and destroyed, playfully, exhilaratingly. Hence, for art to exist, there must be an abundance of force, a personal vital intensity that spreads out into the world creating and destroying forms and objects. That is the essence of art: the drive behind it is nothing but the same creative and destructive energy underlying all action in the world.

So how exactly does this great energy work? By taming a large number of impulses to form a harmonious, beautiful whole. This process happens in the natural world, for instance: every living creature moves according to a certain rhythm, and every living creature naturally generates its own rhythm as part of its life, so much so that we can actually define life as a spontaneous, rhythmic mechanism. This is clear from our own personal experience: we would rather engage in rhythmic than disorderly effort. In sporting practice and other physical activity, by repeating the same movements in equal time intervals we use our muscles efficiently thus saving a great deal of energy and avoiding unnecessary fatigue.

The idea of rhythm underlies life and movement within both the organic world and the inorganic world. There is rhythm wherever there are forces that are not in balance with each other: cold and heat, humidity and dryness, density and expansion, light and darkness. Everything that exists has a natural tendency to fight, and thus rhythm is generated from the counteraction of opposites: the rhythm of the seasons, the cycle of day and night, rainfall and drought, hunger and satiety. As Heraclitus said, all occurrences are in some way connected to rhythm. From this we can conclude that life, existence and evolution are all about creating balance to counteract an underlying unbalance, controlling disorder through regularity and organization, creating a world, an order, from chaos.

Similarly, art is not the boundless unfolding of sentimental longings or wild fantasies, but the successful pairing of content and form, inspiration and technique. And the more the creative force behind the artwork is contained and controlled within the limits of an artistic form, of a rhythm, the more sublime the results will be. So where does this theory take us?

When we listen to good music, we experience this very human desire for depth, infinity and essence; when we look for sublime thoughts in times of calm reflection, we risk upsetting the correct balance between form and content. The best kind of music should content itself with the ways of our world and our lives, and should love them just as they are, as simple appearances, without trying to surpass them by looking for some transcendental meaning. Music, as an interplay of melodies and rhythms, is in some sense a privileged way of thinking about the truth behind appearance, since its very artistic form allows us to understand the world — not in a profound way, but as a tragic-Dionysiacal creation-destruction way. The artist’s rhythms, songs and harmonies, those which inform his work, refer to the Earth and to life, which is nothing more than a swing alternating between birth and death.

What’s interesting is that music doesn’t have to originate from pessimism or asceticism, as Schopenhauer thought. In fact, it could even become the true countermovement of pessimism: “I would only ever believe in a god that could dance”, said Nietzsche. Which is something like asking music to be the art of lightness, of versatility, of subtlety and of pure joie de vivre. What music teaches every human being is to live every moment fully by controlling the chaos, giving life a meaning and imposing a certain order, a rhythm, a shape to its unpredictability and its temporality, giving it a universal shape and directing it towards specific goals. If this process is not followed through, then one will be overcome by chaos, by a multitude of impulses, by the unpredictable, ever-changing determinations that are all around us.

In conclusion, the music that manages to overcome chaos is the type of music which can be said to be life-affirming, that which is in synchrony with human well-being and which is capable of ordering time, rather than passively and nihilistically succumbing to a seductive aural chaos which, while superficially appealing, is harmonically and melodically disorganized. This is how Nietzsche envisioned Dionysical music — on stage, the music should be playing on it own, with no distractions, free to inspire a sense of vitality. The best form of music, therefore, should be absolute music, a representation of both the beauty seen as the form of that which has been overcome, but also as the sublime which continually breaks any form induced by an impulse of a new and profound fullness.

Diego Sánchez Meca

- Details

- Written by Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca

|

Contributor: Dr. Diego Sánchez Meca, |

|

This article is about the theatrical release in Madrid of "The Name of the Rose".

Jokes, word play, irony and a good sense of humour have always been key elements in human relations. The various forms of comedy performances, or the jokes that find their way into our daily conversations, contribute to our moments of laughter, a mechanism with a clear relaxing and therapeutic function, helping us cope with life's worries, anxieties and struggles.

In all the above situations, laughter and wellbeing are generated by our intelligence, creating a kind of oasis in the desert of seriousness. Or to put it another way: ingenuity, irony, jokes and comedy are all tools that we subconsciously use to take a serious situation lightly, or conversely to take light situations seriously.

On the opposite side of laughter is sadness and rigidity. Laughter is carefree, light, it provides us with feelings of enjoyment and wellbeing. It is our desire to increase and intensify the moments of laughter that incite and stimulate ingenuity, irony and parody, which are nothing more than intelligent forms of criticism. The times when the enjoyment we get from laughter is at its peak are the times when ironic, parodic or humorous criticism towards people, situations or institutions allows us to see their ridiculous side. That's why laughter has such a strong destructive power, and why it represents the most effective weapon against fear and authority, respect for truth, compliance with law or veneration of the sacred.

It's not such a mystery, then, that laughter is the most dangerous tool when it is directed towards the established order. This is valid in politics, science, religion, morality or social relations. It throws down the pretensions of the absolute and the sacred, used to teach us laws, traditions, truths, principles, beliefs and norms. "Laughter kills more than anger", according to Machiavelli.

It's easy to understand, then, why no totalitarian state could ever permit laughter and entertainment. The strategy of political domination is always rooted in fear, and humour is the best weapon to dissolve fear. That's the reflection that one gets from the speech by Jorge de Burgos - the blind monk in Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose - when justifying the killing of all those who had read the second book of Aristotle's Poetics, lost since Antiquity and found again by chance in the library of the old monastery. It was a highly dangerous book, because its plot, developed no less by the greatest and wisest philosopher known since then, was in fact comedy and laughter:

"When the villager laughs, it makes him feel like a master, because laughter has reversed the relationship of domination. Laughter conquers his fear, which in reality is the fear of God. We must destroy this book, which presents comedy as medicine and liberation, because it brings about the overthrow of order which can only be maintained through fear."

There are certain things which weigh down on us and inexorably direct our lives: dogmas, absolutisms, the undisputed: it is only when irony and laughter show us the ridiculous side that they stop imprisoning us with their chains - something which, however, does not come without its high cost... Today, for example, one can still be persecuted and killed for showing irreverance towards the prophet Mohammed. And we are still not permitted to joke with what for some is still sacred, serious, perfect.