- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

One morning in Paris, I meet with one of the great French intellectuals, philosopher and Minister of Education during the years of Jacques Chirac’s presidency of the French Republic, Luc Ferry (1951). Before delving into the transhumanist movement which led him to study biological science for three years and specialize in genome sequencing in order to write his book The Transhumanist Revolution, we begin by talking about his other books: Learning to Live or The Revolution of love, which has more than a purely reflective role; he describes philosophy as a tool in the search for a good life. “The idea has nothing to do with happiness as we generally understand it, but with the problem of making sense of life. The purpose of life in our historic moment is love”, he says. Happiness would therefore be the satisfaction of ethically fulfilling that which gives purpose to our life.

Author: Elena Cué

Luc Ferry

One morning in Paris, I meet with one of the great French intellectuals, philosopher and Minister of Education during the years of Jacques Chirac’s presidency of the French Republic, Luc Ferry (1951). Before delving into the transhumanist movement which led him to study biological science for three years and specialize in genome sequencing in order to write his book The Transhumanist Revolution, we begin by talking about his other books: Learning to Live or The Revolution of love, which has more than a purely reflective role; he describes philosophy as a tool in the search for a good life. “The idea has nothing to do with happiness as we generally understand it, but with the problem of making sense of life. The purpose of life in our historic moment is love”, he says. Happiness would therefore be the satisfaction of ethically fulfilling that which gives purpose to our life. He adds: “Love is both the foundation and at the center of family, it does not only affect our private life but the revolution of love, which is the sacralization of people and transcends to public life. Citizens request that the State protect their private lives because when we help our children, in reality, we are helping the future of humanity."

And now let’s continue by talking about your intellectual journey. Your latest book is titled The Transhumanist Revolution. What is transhumanism?

Transhumanism divides into two different fields: one is to improve and reinforce humankind as much as possible in the fight against old age and death. However, we will remain mortal as long as intelligence is incarnated in a biological body because sooner or later we will die. The other field is directed at posthumanism, the manufacture of a new species, a hybridization of man and machine equipped with a strong intelligence which is autonomous and practically immortal.

So the general concept of transhumanism would be...

It would be the transition from a therapeutic medicine to a medicine which repairs and improves.

What are we improving? What are they fixing?

It is a question of increasing life expectancy, making it possible for people to live longer and in better conditions. Transhumanists want to make people live for a hundred and fifty years, two hundred years, three hundred years, and I think it is great because there are so many women to love, so many books to read, so many languages to learn...To die at the age of one hundred is a premature death. Transhumanism aims to create a humanity that will be young and old at the same time, resulting in a youthful but experienced humanity.

What do you think about a future, like the one radical transhumanists describe, in which natural human inequalities based on genetic causes are eliminated, resulting in the modification of the human genome?

Thanks to biotechnology, the modification of an individual's genetic heritage is advancing. This modification would be one of free choice: “from chance to choice” thus meaning it would aim to correct natural inequalities. In order to correct social and economic inequalities we have created democracy, social protection, welfare and social security, which intend to diminish the differences between rich and poor. Now we have to match the conditions of those who have not been lucky by nature with those who have as they were born with very good natural qualities. In other words, if you have a child who is born with a disability or terrible illness, thanks to the biotechnological advances protected by transhumanism, the child would be able to live longer and in better conditions. Research on transhumanism started with rats at the University of Rochester in the United States and showed that, by modifying their genome, they were able to live longer. Their lifespan increased up to 30%. This proves that the project is possible.

What is your opinion regarding the most extreme type of transhumanism, that being post humanism?

Google’s Singularity University is developing the project of posthumanism by creating strong artificial intelligence. It consists of producing artificial neurons on a carbon-free silicon base. In fact, as the researchers are materialistic in the philosophical sense of the term, they believe that humans are machines, unlike Christians who believe that humans are composed of body and soul. For that reason, one day they will build a non-biological brain as for now it is only a matter of complexity that stands in their way. In doing so, they will create a post-humanity as they produce a technology that is similar to ours, with a conscience, the ability to apply free will, freedom, emotions, anger, fear, jealousy and love. A real brain will have been produced but on an immortal basis as opposed to a biological one. I do not believe in this because in order to have feelings you need to have a body, but post-humanity researchers argue that all feelings are found in the brain.

But how scary, if that were to be the case.

Although I don't believe in posthumanity, Steven Hawking, Bill Gates and Elon Musk do believe it will happen. In July 2015 they signed a petition with eminent scientists and researchers from around the world about the dangers of artificial intelligence becoming too strong. Musk believes it is the greatest threat ever invented by mankind.

I spoke to the most important person in the field, Facebook’s CEO of artificial intelligence, and asked him if he believes we are going to be able to produce this strong artificial intelligence, to which he replied it is only a matter of time.

So for me, there is no reason to fight transhumanism because everyone wants to live longer, have more experiences and a higher level of intelligence. On the other hand, posthumanism will be dangerous to humanity because we will turn into domestic pets, due to the superior capacities these hybrids will possess.

Everything we have discussed from the dangers of genetic manipulation to strong artificial intelligence suggests a need for ethical and political regulation. Are you optimistic in this regard?

I am not a pessimist but we will need regulation which will be difficult for three reasons. Firstly, it is very difficult for politicians to understand due to a lack of scientific knowledge. Secondly, research developments are made too quickly and consistently. And the third reason is globalization. If the regulation is only Spanish, German, French or Italian, it is meaningless as it only prohibits a certain number of things specific to one place and is not applicable to others. For example, insemination with the sperm of a stranger is prohibited in France but permitted in places like Belgium and the UK. This becomes useless and insignificant because it encourages medical tourism, therefore resulting in it being pointless to only restrict it in some countries. In our opinion, regulation should be universal, at least across Europe if not all over the world.

Do you think this research on genetic manipulation is done for altruistic reasons or as a money-making scheme?

Both! Just like the laboratories! I worked with laboratories for a long time and they earn a lot of money. Imagine that instead of an anti-wrinkle cream you can have a pill which destroys what we call senescence or old cells. These cells multiply in our bodies as we reach the age of fifty and cause grey hair, wrinkles and cancer. They make us grow old and get sick. Many biologists are working hard in order to find a way to destroy these senescent cells. Imagine how much money these laboratories and biologists would make if they were to create such a pill!

Absolutely! Instead of buying a cream, millions of women and men would prefer the pill.

It’s true. In addition to generating a lot of money, it will also greatly benefit society. Five years ago the biologist Raymond Schinazi discovered a medicine able cure the worst cases of Hepatitis C with a six-week long treatment with 98% success rate. This treatment was quite expensive and cost about $50,000 but it was wonderful because many people could benefit from it and recover. I believe people still want to live longer and therefore the benefits of investing in biotechnology are enormous. That is the reason why Google invests billions of dollars in biotechnology.

Have you spoken to anyone about the research into cancerous cells in an attempt to make them mortal again?

Yes, of course! It is very interesting. Google's activities are based on the artificial intelligence that deals with the genome or DNA responsible for sequencing cancerous cells. These cells are almost immortal when you try to kill them. Thus, once the DNA of a cancerous cell has been sequenced, it has information about its weaknesses and how to attack them. This method is called precision therapy or personalized therapy. After debating a lot with Google's CEO, he told me that cancer will be defeated in 20 - 30 years’ time thanks to artificial intelligence and advanced technology. Laurent Alexandre also shared that doctors will not be the deciding factor in this fight, but rather the computers. While the human brain takes 40 years to sequence the genome of a cancerous tumor, artificial intelligence does it in a minute. This makes it possible to detect the weaknesses of cancerous cells and attack them using effective medicine. Artificial intelligence has ramifications on collaborative technology and biology as well.

As you said in your book, collaborative economy has been made possible thanks to the infrastructure of the internet and its communication networks, with examples such as Uber, Airbnb, BlaBlaCar... How do you think this new economic organization based on sharing will affect a capitalist system like ours?

This is pure and simple capitalism! The novelty in the collaborative economy is that non-professionals can compete with professionals thanks to the technological infrastructure. It is a question of objects connected within a smartphone by only three things: artificial intelligence, big data and captor. The internet gives non-professionals, non-hoteliers, non-restauranteurs the opportunity to compete with professionals. This is Schumpeterian capitalism! Innovation makes it possible to compete with professionals, like Uber and taxis. In order to understand it further, you have to read Antigone by Sophocles.

What does Sophocles' work teach us about these start-ups?

There is a pattern of conflict between Airbnb and hoteliers, Uber and taxi drivers, or BlablaCar and car rental companies. All conflicts are violent, such as the conflict that confronts Antigone and Creon. Creon, the king of Thebes, says to his niece Antigone: "We cannot have a funeral ceremony for my nephew Polynices, Antigone’s brother, because he betrayed the city.” Antigone replies: "But he is my brother and I love him, so I don't want them to feed him to the dogs or birds, I want a funeral ceremony for him." This is the conflict between Creon and Antígone, who are both right. The Greeks consider this a tragic conflict because it is not between good and evil but between good and good. Airbnb is right! Hotels are right! It is a conflict between equivalent legitimacy. Airbnb's private shareholders say let us put our rooms on the market. While hoteliers say we have more regulations to comply with: security, fire, employees, social charges etc. It is an unfair competition. Both are right, that’s what is interesting.

What do your colleagues think?

French intellectuals are pessimistic regarding transhumanism. They stand against a collaborative economy and the new world that is just around the corner. However, the decrease in poverty in the world was the most notable achievement by the end of the 20th century. The world is much better today than it was before: there are human rights, women’s rights and democracy along with many other things that are improving. However, our intellectuals claim the opposite; they are not in favour of globalization, transhumanism, new technology and anything else in the sector of science and economy. The main objective of philosophy, before being about trying to understand the meaning of life, is in fact to understand the world we live in. There are two things occurring: the first one is globalization and new technology and the second one is revolution; a revolution of love and transhumanism that is changing our world. It is very interesting!

The philosopher Luc Ferry. Photo Elena Cué

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

This year’s Berggruen Prize for Philosophy & Culture, endowed with $1,000,000, has been awarded to Onora O’Neill, Baroness O’Neill of Bengarve. In addition to her teaching work at Columbia and Cambridge Universities, O’Neill is a member of the House of Lords, a member of the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission, a former Chair of the British Academy, a member of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics and a member of the Human Genetics Advisory Committee. O'Neill's work has centered on the ethical and moral tradition of Kant, building on freedom governed by individual duty, where duty takes precedence over individual rights in the quest for a more moral, autonomous society. A day before she received the prize, I spoke with Onora O’Neill in the bustling lobby of her New York hotel.

Author: Elena Cué

This year’s Berggruen Prize for Philosophy & Culture, endowed with $1,000,000, has been awarded to Onora O’Neill, Baroness O’Neill of Bengarve. In addition to her teaching work at Columbia and Cambridge Universities, O’Neill is a member of the House of Lords, a member of the UK Equality and Human Rights Commission, a former Chair of the British Academy, a member of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics and a member of the Human Genetics Advisory Committee.

O'Neill's work has centered on the ethical and moral tradition of Kant, building on freedom governed by individual duty, where duty takes precedence over individual rights in the quest for a more moral, autonomous society. A day before she received the prize, I spoke with Onora O’Neill in the bustling lobby of her New York hotel.

I would like to start by talking about the significance of the Berggruen Philosophy Prize you have just been awarded.

There have not been big prizes in the humanities and social sciences. I think the prize reflects the foundation’s leadership role in the realization that nowadays to say science is science and nothing else is needed is an obsolete statement. Take a topic like the ethics of data use, a very hot topic today; you cannot approach it merely on the basis of having the best computer scientists and technologies. We also have to take into account ethics, politics, what can and should be regulated. My experience is that Berggruen are absolutely up there with this movement who think we must take the normative, that is the ethical and political questions, and the legal questions just as seriously as we take the scientific questions.

What is it about Kant that makes him such a key reference for you?

In the twentieth century, particularly since the 1930’s, currents of thought such as logical positivism claimed that ethics, together with metaphysics, religion or aesthetics, were literally meaningless. They consist of a mere set of statements that cannot be justified. This way of thinking spread to many universities, from Argentina to Canada, to Australia, USA and the United Kingdom. There was a public response to that nihilism, the Human Rights Movement, The Universal Declaration in 1948 and the European Convention in 1950. The institutions responsible for the fulfillment of these rights were created. The issue was that this impulse to restore an account of justice had abandoned ethics. It was thought that ethics are personal, subjective. Some spoke of personal values, chosen by each person, which in turn created a need for a public debate on common ethical criteria. That is where Kant can provide his arguments. My questions were “Does he have the arguments?” and “Are they good?” That is what I have spent all these years trying to work out. Because Kant does not think that the individuals who act are isolated, but that there are common reasons that a plurality of people can adopt.

Yes, but it is difficult to follow Kant ethics.

Indeed. If I want to have a reason that can become a reason for everybody, for example, an ethical claim, a political claim or a claim about justice, I have to make sure what I give as the reason can be acceptable for everyone. They do not necessarily all have to agree with it, but they all have to be able to understand it as a reasonable way of acting. That to me is the way in which Kant is interesting.

As you well said, trust is one of the foundations of society. What do you believe to be the reason we have reached such a general widespread lack of trust today?

The empirical evidence for the lack of trust is much worse than people think. When we actually look at the polls, we find variations in different countries, but the polling evidence in the UK, for example, shows trust in certain people, such as politicians and journalists, was very low 25 years ago and remains low to this day.

What is your opinion on the lack of respect for the deontological codes in some public institutions?

In the UK people continue to trust in professionals such as judges and nurses. But it is true that some parts of the media behave very badly. I was astonished by the New York Times these past few days and their campaign against President Trump, perhaps with good reasons but what a campaign nonetheless. In regards to trust in general, we have to talk about trustworthiness instead, because we only trust people or institutions that are trustworthy. If they are not, we mistrust them.

Is this a legal problem or a moral problem?

I think it is a mistake to emphasize rights so much without integrating them with duties. The heroes and saints of the past thought about what they ought to do, not what they ought to get. Because what we ought to do is a basic question. For example, in World War I there was emphasis on patriotic duty, the idea of duty to serve king and country. Then when the war proved to be so terrible and disastrous, people turned against patriotic duty. However, duty should not be something related to subjective and personal values. We have to share values in order to live in a society and we need a certain explanation of why these values can be universal.

On the basis that you cannot be a moral individual unless you are free, how do you perceive freedom?

We should not fall for the misconception of freedom and autonomy. Human freedom can be used for moral purposes or not. But it is used for moral purposes only when in action we adopt principles that are valid for everyone. Kant never talked about autonomous persons, because it is not the person that is autonomous, it is the principle. If autonomy were to correspond to the person, moral acts would only be individuals’ arbitrary decisions, as advocated by existentialism. Certainly, I can use my freedom to adopt morally important principles such as not enslaving people or I can use it to coerce other people when it suits me.

Yes, the use of it as a medium and not as an end is frequent...

We live in a world where people are using the metric of consumer benefit for everything, even for information and communication, or in the use of social media to send messages and content to certain audiences and not others, depending on what suits them.

What do you think about the use of lies in the rise of false news on social media?

Not deceiving is one of the fundamental duties. When I think about technology, I wonder whether we will have democracy in 20 years because if we cannot find ways to solve this problem, we will not. People are receiving messages and content which is distributed by robots, not by other human beings, let alone by other fellow citizens. It is frightening.

Internet is a problem for us because we can’t keep up with all the changes and create appropriate legislation.

Even if we were to regulate the part of the internet most people access, it would be very difficult do so. Firstly, because of the multiple jurisdictions and secondly, because it is technically very hard to demand that social media websites and internet service providers operate as publishers. If the information is posted with a proper ID, then the individual is responsible for the content, but if it is anonymous, the internet service provider would have to assume responsibility. We are living in dangerous times. The misuse of the public channels of communication is so polluting and so powerful that it undercuts the basis of proper democratic politics. Perhaps we will be pushed to do what the Chinese have done and use censorship.

Society has progressed astoundingly yet it does not seem like this progress is making people happier. Depression is the most widespread mental illness and in Spain, for instance, suicide is the main cause of unnatural death each year.

It is extremely frightening and it is very hard to know what is actually happening. Each tragedy is an individual one, but it is not uncommon for people to feel that nobody loves them, that everybody hates them and that they are worthless. Sometimes, within schools children gang up on one particular child. We read stories about parents having to move their children to a different school. It is crucial to keep good communication with one’s child because once they hide away it becomes an enormous problem. My son and his wife, for instance, make sure their son has a great deal of sports, music and activities at a school. When I was young, I didn't think that was so important. Now, it is proven that if a school organizes sports, not just for the sporting elite but for all children, it is demonstrably much better. It is the same case with all other activities and social competitions.

There is a great distrust amongst people in the way biotechnological advances in food and medicine affect health. In which ways are bioethics committees useful?

One of the most important things is to try to teach people from an early stage of life to look for the evidence and respect it. We should also teach our children to distinguish those who deceive people. We had a problem in the UK with the MMR vaccination. A tiny group led by doctor Andrew Wakefield claimed that the vaccination caused autism upon which a large number of parents decided not to vaccinate their children. It was only good fortune that we did not have a major measles epidemic as it is a killer disease that can seriously damage children. The doctor has since been forbidden to practice medicine in the UK because he was using scientifically disreputable evidence as he chose his examples from children who already had autism. Meanwhile, there were about a thousand studies funded out of public money in order to see if there was any truth in his claims. It was statistical incompetence, a malicious activity that led to this and we have had other similar examples. Thus, we have to learn how to use evidence. We have now got another charity called “Evidence matters”, currently spreading to other countries, which is trying to teach people to be responsible about using evidence. What is the evidence? Where did this evidence come from? Is it good evidence? Is there a conflict of interest with the people who are publishing this evidence? Another example is the term “natural remedy”. What do people mean by “natural”? Chemicals are natural. People don’t want any chemicals in their food but even if plants are grown without any fertilizers they would still have a certain chemical makeup.

To conclude, I would like to know your opinion on whether climate change is also an ethical problem.

Yes, of course it is. If climate change is happening in a way that is anthropogenic, meaning man-made, then we can do something about it. What one has to do is try to read the evidence and see to what extent it is anthropogenic. I think the consensus is that it is, in part, man-made but of course, there are other sources of climate change but the evidence amounts.

Onora O'Neill. photo: Elena Cué

Onora O'Neill: What we don't understand about trust

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

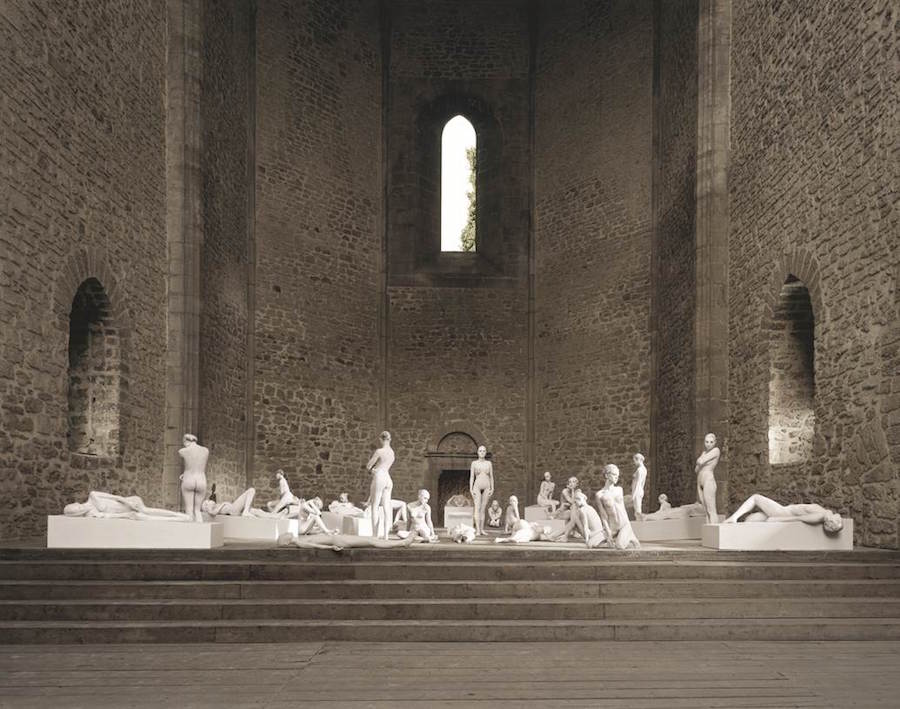

The new space created for large art exhibitions Pio Pico in Los Angeles, founded by Federico Spadoni, opens its doors to the public for the first time and until March, will host an exhibition based on the notions of classical sculpture by the multidisciplinary artist Vanessa Beecroft (Genoa, 1969). She is internationally known for her iconic conceptual performances which often include historical, political or social references associated with the place where they are made. Subsequently filmed and photographed, these solemn groups of hieratic naked or half-naked women coexist in a form of sociable unsociability. Beecroft suffered from eating disorders since the age of 12. This obsession with food led her to write a diary of all the foods she consumed for ten years: «The Book of food».

Author: Elena Cué

Portrait of Vanessa Beecroft 2015 polaroid. Pico Studio, Los Angeles photograhed by © Federico Spadoni, 2017.

The new space created for large art exhibitions Pio Pico in Los Angeles, founded by Federico Spadoni, opens its doors to the public for the first time and until March, will host an exhibition based on the notions of classical sculpture by the multidisciplinary artist Vanessa Beecroft (Genoa, 1969). She is internationally known for her iconic conceptual performances which often include historical, political or social references associated with the place where they are made. Subsequently filmed and photographed, these solemn groups of hieratic naked or half-naked women coexist in a form of sociable unsociability.

Beecroft suffered from eating disorders since the age of 12. This obsession with food led her to write a diary of all the foods she consumed for ten years: «The Book of food». This diary was the center of her first performance in Milan in 1993 where she made herself known to the world of art. The presentation also included the «living sculptures» of 30 women with eating disorders, wearing their own clothes and moving through the space where the demonstration took place.

It could look like the other side of the mirror...What is autobiographical about your performances?

The emotional impact, narrative and certain traits of women. The relationship with the public which is confrontational or, as Dave Hickey defines it, there is a separation, a use, in addition to governing rules that do not apply to us.

You said “The day I decided to use The Book of Food as art was the day I stopped”. Does art heal?

Art does not heal. It transforms aspects of life into an iconic and permanent form. It translates pain into something universal that transcends life in its immediacy.

vb52.002.nt. Castello di Rivoli, Turin, Italy, 2003. © 2017 Vanessa Beecroft

As an Italian, you will have grown up surrounded by the history of art, in a natural way. Which sources provide the artistic inspiration for the aesthetics of your performances and photographs?

In Italy, as a child, culture became a landscape and an immediate background. Instead of a flower you’d see a Laurana head or a Pollaiolo painting. You were raised not seeing the difference between a girl, a Piero della Francesca portrait, and a random religious painting on a fresco on your walk to school. The sources of my inspiration became the paintings and sculptures of the 15th and 17th century, and the architecture of any era.

What type of beauty does your art convey?

A beauty that is equally particular and universal, that tends to be idealized but comes from the street. A beauty connected to the human form, the female form in its artistic, cultural and social representation. I use beauty to relay other hidden messages.

Vanessa Beecroft. vb62.018.nt, 2008, Spasimo, Palermo, Italy. Photo Nic Tenwiggenhorn, Courtesy of the artist

That mystery makes your work open to different interpretations which creates a lot of controversy. How do you perceive the women you represent? Why collective and not individual?

The women are often there as a physical equivalent of what I am going through. She is not alone because she is speaking for a group, for more than one person and because a group is stronger and more convincing than an individual. The women have similar aspects but there are also differences between them. They are organized in a hierarchical formation in which there are privileges and unbalance, symmetries and color-schemes.

You have been defined as a feminist. What does feminism mean to you?

The fight of women to survive in a society built by men, mostly white men. Feminism today cannot be the same as it was in the past. The new feminism is stronger because women accept their womanhood, their body and their maternal power, while before they were forced to deny their identity as a female since it tied them to so many bad memories.

Vanessa Beecroft. vb48.006.dr, 2001, Palazzo Ducale, Genoa, Italy. Photo Dusan Reljin, Courtesy of the artist

You have collaborated with the rapper and designer Kanye West over ten times. Your presentation of his new clothing line Yeezy Season 3 and his album The Life of Pablo in Madison Square Garden became the most-viewed performance art in history, with over 20 million viewers. How has this collaboration influenced you?

We dealt with a larger audience than the one of the art world and a general audience that had to perceive a message in a more direct way. The social impact was greater and the artistic value could be less subtle. Kanye’s work intended to go beyond its artistic value, to the point it affected his own life. I was influenced on a human level and after the experience, I longed to be in the artist’s studio.

What is it about your relationship with Africans that makes you feel autobiographical when you work together?

I only work on matters I can identify with.

Installation view, untitled (tableau) 2017 pio pico, Los Angeles courtesy of the artist © Vanessa Beecroft

Your iconographic framework has always involved the human figure, almost exclusively the female one. What is the meaning of the body as an instrument in your art?

It’s the most direct way of talking about humankind, in this instance of a woman, my own experience, and a shortcut to use forms, lines and colors on the subject closer to me: myself. However, I do not consider the body to be something physical. The body is there to express intellectual thoughts, emotions and formal solutions.

Your new sculptural work, for Pio Pico’s inaugural exhibition in Los Angeles, is inspired by notions of classical sculpture. What can you tell us about this series?

The sculptures have been molded by hand in clay, from the source material I could find in LA. I molded them without a plan just as when I sketch. Then they were fired in various colors’ clay. Some survived the kiln, but many didn’t. I assembled them in a performance-like group using materials like wood and beeswax as support and as a way to add a bit of coloring. There is also a large mural which represents the body imprint of a group of women, mostly African-American. The imprint was made on clay and a positive in plaster is exhibited. I wanted to realize a negative in ceramic but it was too difficult to achieve an optimal result for this exhibition.

There are also bodies…

Yes, classically inspired large sculptures of clay. One of them has exploded tonight. The other one is put together roughly by beams of wood. I don’t think of sculpture as a category. I think of all disciplines as a way to relay my story.

Untitled (gray body), 2017, digital c-print with diasec © Vanessa Beecroft, 2017

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

With a warm welcome, one of the most renowned painters of the American artistic scene opens the door of his house to us in New York’s West Village. Frank Stella (Massachusetts, USA, 1936), precursor of minimalism at the time when abstract expressionism led the artistic panorama, shows me the layout of the rooms in the museum where 300 of his works, dating from the end of the 50s until today, will comprise his next exhibition. Whilst holding dear the memory of the great retrospective through which the Whitney Museum of New York paid homage to him, today it is the NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale in Florida that will inaugurate, this November 12th, the exhibition which covers 60 years of his career. The artist invites me to take the elevator to the second floor, where after preparing a coffee, we evoke his life and trajectory.

Author: Elena Cué

Frank Stella en su casa del West Village, Manhattan. Photo: Elena Cué

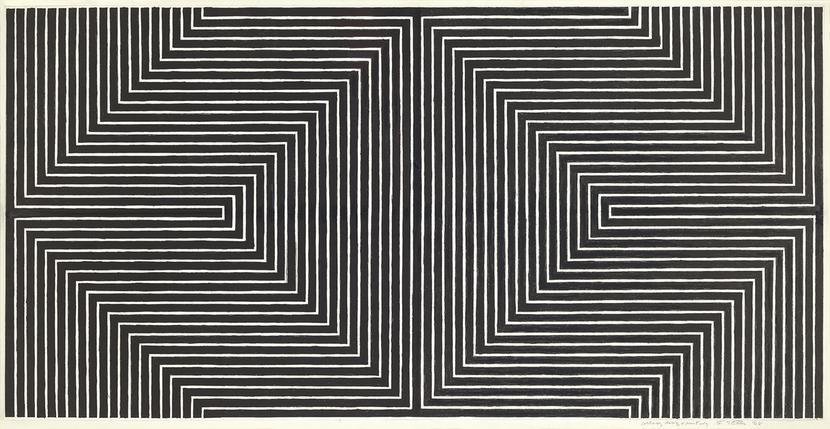

With a warm welcome, one of the most renowned painters of the American artistic scene opens the door of his house to us in New York’s West Village. Frank Stella (Massachusetts, USA, 1936), precursor of minimalism at the time when abstract expressionism led the artistic panorama, shows me the layout of the rooms in the museum where 300 of his works, dating from the end of the 50s until today, will comprise his next exhibition. Whilst holding dear the memory of the great retrospective through which the Whitney Museum of New York paid homage to him, today it is the NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale in Florida that will inaugurate, this November 12th, the exhibition which covers 60 years of his career. The artist invites me to take the elevator to the second floor, where after preparing a coffee, we evoke his life and trajectory.

You were born between two World Wars, to a family of Italian inmigrants. What memories do you have from that time?

I have some strong memories due to of the war but mainly I remember right after it, when it was all about the destruction and rebuilding of Europe and America. It was a very fast-moving and dynamic period. There was a lot of real growth and an incredible optimism that nobody has seen since; it was amazing. In a way it was a very happy time, everybody was so glad the war was over that it created a kind of momentum to go on.

What was the start of your artistic life in the 50s when the scene was dominated by Jackson Pollock, Nauman, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschemberg...?

It was very active but at the same time very relaxed. There was a big change, not just in the art world but in general. I was just one of many young artists. I think partly because of the war, a lot of the European artists came to the US in the late 30’s and the American artists who were here benefited from that but the abstract expressionists were slightly older. Then there was a whole generation of younger artists who were supported, in a funny way, by the government because of the GI Bill. Americans could study in Europe funded by the government which created a bunch of artists. It lead to a combination of European artists coming here and Americans going to Europe and then coming back. There was a lot of activity and a lot of it was quite relaxed because people just made do with what they had in terms of money. It was possible for almost anyone to get a working space and to have enough work on the side in order to keep creating art. Everybody was working and exhibiting. There were exhibition opportunities, which means showing your work, and that’s what artists really care about. They like to get paid for their work but what really bothers them is to not have it seen.

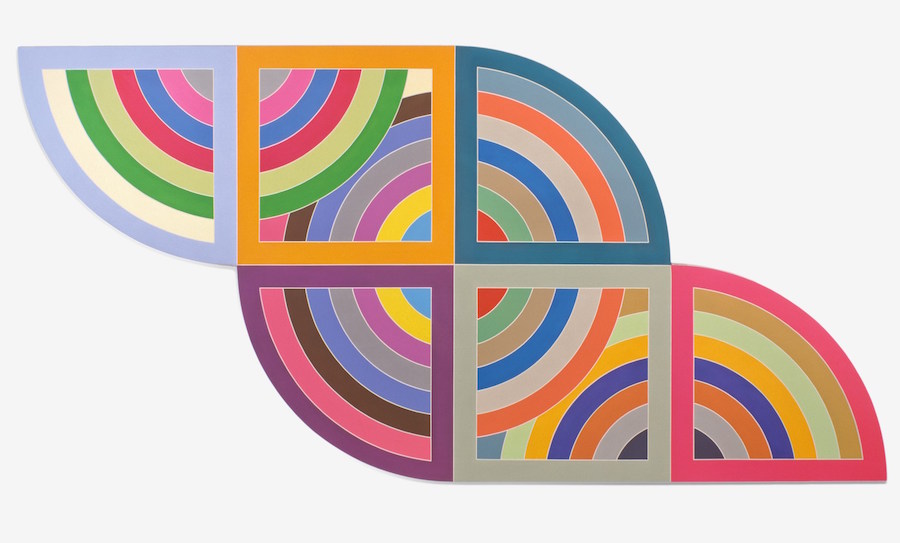

Frank Stella. Harran II

In this decade, when abstract expressionism, which profoundly shows the emotional dominated the artistic sphere, you opted for a more formalist art...

I think there is a slight misunderstanding. They said my paintings were less emotional but they were just trying to create a sense of organization, to build a structure that you feel you can work from, but I like the chaos. In a way, it was trying to find out what was under the chaos because the chaos of abstract expression is so powerful. I think to a certain extent it’s easy to see that underneath the painting that seemed so wild in America, was the structure of painting in Europe up until the late 30s, which was basically Cubism and Surrealism.

When you look back to where you began, to your Black Paintings from the 50s, what do you see?

I see two things, two paintings. The paintings just before the black ones which are kind of black and a lot of different things. And then I see that something happened and I decided to make it a little bit more symmetrical and organized. There are basically two parts to it: the part that is very much a version of abstract expressionism and then the part that is firmer and more organized.

Frank Stella (1968) Black Study

You started making black paintings in the 50s and in the 60s you introduced color, even florescent color...

I think it was inevitable. My father was the first one to say, “color sells”. You can get the same advice from almost every art dealer in the world. The critics are sometimes even more childish than the artists with ideas like “there is nowhere to go now, it’s all black”. I maybe repeat this too often but I think if you played my career backwards, so if we started from now as the beginning, played it back and ended with the black paintings, I think people would be a lot happier.

Your Irregular Polygons series (in the 60s) marked a turning point in your work. Can you explain why it was so important?

Like everything, there is always a large part created by accident. In general, abstract painting, which is what I wanted to do, is largely expressed in terms of what started with Mondrian and Malevich which is basically a form of geometric painting. The basic idea was that you had a flat surface and you made a geometric pattern, but usually the geometric patterns were dividing the space. I was looking for something that would still be a kind of geometry, but a geometry that was more dynamic or fluid and then something happened by accident. I focused on a Malevich painting that caught my attention, a well-known painting. It was a white ground, a black rectangle and there was simply a blue triangle laying on top of that black rectangle. I was thinking about it and then suddenly it struck me that what was interesting was that what most geometric paintings did was put one thing on top of another. And what I was looking for was making the triangle penetrate the rectangle so that you went around it and made a shaped canvas. It was as though you took the background away from the Mondrian and let the triangle and the black rectangle exist on the same plane. So it was a slightly different way of looking at the geometry but to me it actually seemed more dynamic and exciting and offered a lot of possibilities. It’s all Malevich’s fault.

Frank Stella. Irregular Polygons: “Ossipee II” (1966), “Chocorua IV” (1966), “Effingham IV” (1966) y “Moultonville I”I (1966)

In 1970, at 33 years old, the MoMA exhibited a retrospective of your work and your latest achievement was to receive the National Medal of Arts by President Barack Obama. How does this recognition affect your life and your work?

We talk about age and I’ve been lucky to live a long time. I was young when that happened and, if I were to explain with metaphor from the sports world I’d say, when you’re playing the game and you're in it, you don't really think much about it because you have to react to what’s going on and you just do the best you can. So in a way I didn’t really think too much about it. It was very exciting but I was just one of many artists who were relatively young and were experiencing really successful and exciting careers. We were all working so much, there were a lot of ideas around, a lot of things happening. After all, at the same time I had that exhibition you had color field painting, pop art, second generation abstract expressionism and that’s not to mention what was happening in sculpture with people like Michael Heizer, Richard Serra and Chamberlain. So there was so much going on that I never felt separated, I felt part of it. Before that retrospective, one of your black paintings was exhibited in the MoMA . There’s an interesting story about how they bought it. The head curator Alfred Barr liked it but he knew that it wasn't going to be popular with the board of trustees or the other curators. But Alfred Barr had a fund and was allowed to buy anything he wanted for the museum that was under one thousand dollars. I remember that Leo Castelli called me up and said that he was going to sell the painting “Marriage of Reason and Squalor” and we had agreed at the time for one thousand two hundred dollars but he was going to sell it to the museum for nine hundred. I said “I don’t want to do that, that's crazy. Why are we doing that?” To which he said “Frank, get it together, it's the Museum of Modern Art”. There was no way it would have gone there for any price except for the price that Alfred was able to buy it under his own stipend. It didn't just happen because they loved it so much.

Your Moby Dick series appears to be a obsession given that you dedicated, on and off, 10 years to it. What was it about Melville’s book that impacted you so much?

In some ways, I was reluctant to do it, but it had such an appeal to me for one main reason. Above and beyond the power and the beauty of the story and the incredible language of Melville, it is really a story of going around the world, about traveling and there was something about that, that to me, seemed to allow you an incredible kind of freedom. You can take plenty of time and it didn't all have to be the same. It allowed for the introduction of different ideas and different ways of thinking about things. It was really very open ended while at the same time it gave you a structure or outline to work with.

“And may God hunt us all if we do not hunt Moby Dick to the death!”. What do you consider to have been your impossible battle? Maybe with God...

I don't think I’ve had one. In modern times, the artists see themselves as having an incredible struggle against the difficulty of making art but that wasn’t always true. I grew up in a very straight forward way, in a Catholic American-Italian family and never worried about God. In fact, as I grew older I liked God because he had very good taste in art, at least in Italy. I found him to be a kindred figure.

Frank Stella, The Grand Armada (IRS-6, 1X), 1989. Fondation Beyeler, Riehen / Basel, Beyeler Collection. © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

You have used painting as an object. What does continuing to paint mean to you? Why don’t you do installations, performances, conceptual art…?

I make objects and I like to paint on them, one way or another. Actually, the problem with the printer and 3D works is that they get so complicated that it’s quite hard to paint them. I mean literally, in the sense that if you don’t tangle your fingers, it's hard to get in there and paint them. They do have spray paint so in the end you can get in there one way or another. It's a different way of working which for me changed with the Polish village paintings. They became constructions, an enlargement of collage in 3D. When they were made, I realized I was going to start building my paintings and then paint them. That's how it changed and now I just think that way. It’s not a new idea, a lot of people, such as Ron Davis, were doing things like that. I think in a way the shaped canvas lead to that. Once you gave up the regular rectangle, it was a little difficult to build the shape so there was more emphasis on the construction of what you were going to paint on.

At one point in your career your interest in architecture and sculpture grew, was this to the detriment of painting?

It’s not exactly to the detriment of painting. Using the Renaissance as a reference point, almost everybody that made art (at least during the Renaissance, and maybe even at all time) could do architecture and sculpture as well. I mean you can write music and you can also play the piano or the saxophone. But I must say that architecture did have an effect on me when I was younger. Frank Lloyd Wright was a big influence, I went to see his work and it was great. We had a very good library in the town that I grew up in by a famous 19th century American architect H.H. Richardson who had evolved a kind of Romanesque style in America.

Frank Stella. Project: K.304. Location: New York, USA. 2014

Where did your baroque style come from over the last few years?

I guess it is a change. For a while, it was minimalism and then maximalism. As the expression says, you throw in everything but the kitchen sink. It’s easier to add the ingredients but it’s not very programmatic. It’s about how things relate to each other and what the idea suggests. Sometimes, it is a problem for me and I do better when I take things away than when I add more.

How has art changed since Chauvet, Lascaux, or Altamira?

It has changed but I like the early art because it was very straight forward. The big idea was that you made what you saw, it was about observation. There is a lot of talk about the magic and the mystery but I think that is actually wrong. They didn’t have an idea about the development of art, they were trying to picture and live with what they saw. They could have made a lot of pictures of plants or trees for example, but instead they made them of animals because that was a big part of their life.

How do you see the art world now?

It’s an interesting version of what happened in the 60’s. It’s a little bit tricky because there are more artists and opportunities now than ever before. If you take a not-so-positive view of it you can say it has expanded, but is there better art? I don't know if it’s just loyalty to my generation or the way I grew up but I don’t see that the quality of art has expanded dramatically.

Frank Stella. Foto: Elena Cué

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

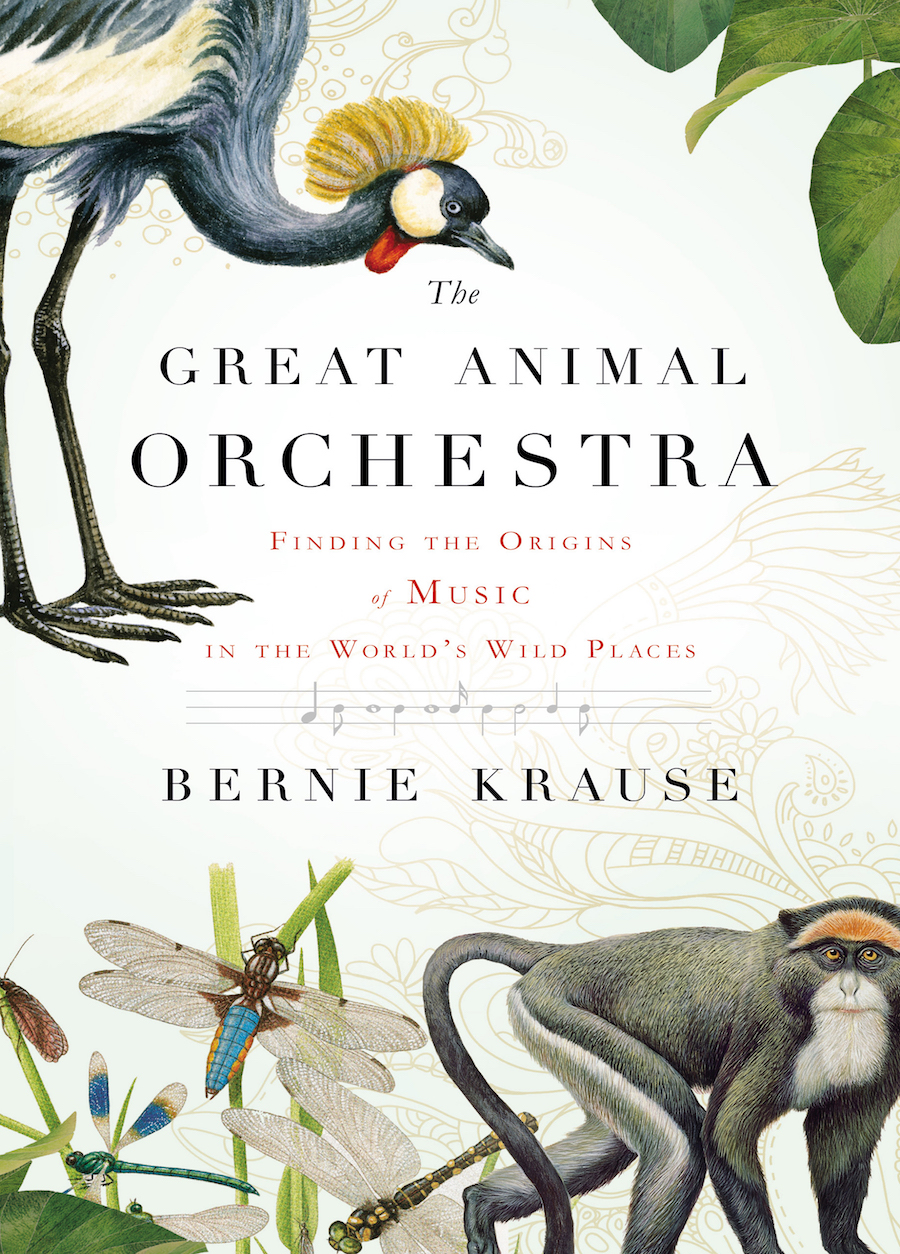

At least that is what the musician, scientist, naturalist and author of the book "The Great Animal Orchestra” (Detroit, Michigan, 1938), Bernie Krause, thinks. He wrote this book to show people that animals taught us to dance and sing and that soundscapes, particularly biophony and geophony, terms coined by the ecologist, have exercised a decisive influence on our culture.mKrause was a member of the famous American folk group The Weavers. When it broke up, he formed the electronic music duo Beaver & Krause. They introduced the synthesizer into pop music in the 1960s, playing in sessions for musicians such as George Harrison, Mick Jagger, Quincy Jones and Barbra Streisand, among others.

Author: Elena Cué

Bernie Krause in St. Vincent’s Island, Florida (2001). By Tim Chapman.

"The truth is the Greek myth got it wrong. It wasn't Orpheus who taught music to the animals, but the reverse". At least that is what the musician, scientist, naturalist and author of the book "The Great Animal Orchestra” (Detroit, Michigan, 1938), Bernie Krause, thinks. He wrote this book to show people that animals taught us to dance and sing and that soundscapes, particularly biophony and geophony, terms coined by the ecologist, have exercised a decisive influence on our culture.

Krause was a member of the famous American folk group The Weavers. When it broke up, he formed the electronic music duo Beaver & Krause. They introduced the synthesizer into pop music in the 1960s, playing in sessions for musicians such as George Harrison, Mick Jagger, Quincy Jones and Barbra Streisand, among others. At the same time, the also worked in film, playing music in over 100 big movies, such as Apocalypse Now and Love Story. For over four decades now, Krause has traveled the world conducting a bio-acoustic study, recording and documenting natural soundscapes. He has archived the sound of over 15,000 species, over half of which have already become extinct on account of man's interference with nature. This material consists of over 5,000 hours of recordings of the sounds of nature.

After a lifetime dedicated to music and sound, what does music mean to you? How would you define it?

Because I don’t see very well, my world has always been informed by what I hear. As a young child, I was first drawn to the sounds of classical violin and composition. In my teens, I switched to guitar and learned all styles. But when I applied to American music schools in the mid-50s with guitar as my major, I was told by the interviewing professors that guitar was not a musical instrument. Shortly after university, I joined, The Weavers. After The Weavers broke up in early 1964. During that period Jac Holzman, then President of Elektra Records, introduced me to Paul Beaver. Together we formed Beaver & Krause. As a duo we introduced the synthesizer to pop music and film on the West Coast and the UK.

Paul and I realized that with the introduction of the synthesizer to musical composition, the standard definition(s) of music had also changed. So we re-defined music as the control of sound. That definition has held true even for the sound design and compositions I and colleagues have rendered since I helped initiate the field of Soundscape Ecology.

Where do you think is the common ground between the sounds of the natural world and music created by Man?

When we lived more closely connected to the natural world, we mimicked the sounds we heard coming from the forests and plains that comprised the environments in which we lived. These expressions included rhythm, melody, harmony, texture, and the structure of sound (composition). By observing the animals move, we copied their journey through space and learned to dance. In North America, there are still Native American tribes that perform a deer dance, or a bear dance, or an eagle dance…all based on an ancient need to show deference to the living world that surrounds and sustains us.

Dian Fossey’s Rwandan research camp (1967), Karisoke. By Nick Nichols, National Geographic

You have recorded more than 5,000 hours of sounds from different habitats, both marine and land, and more than 15,000 animal species. What are the greatest changes you have noticed over these five decades?

Sadly, the greatest change is the overwhelming loss of density and diversity of species almost everywhere I go these days. In some places, like northern California, where I and my wife, Katherine, live, we experienced the first completely silent spring (2015) I can ever remember in the nearly 80 years of my life. There were many birds, but they weren’t singing; it was the fifth year of the historic drought that descended on our section of the continent. The biophony (collective sound produced by all organisms in a particular habitat) returned to some degree this season likely because of the significant amount of rain we had this past winter, extremes of weather that are most likely a direct consequence of a drastically changing climate.

With so many years of experience observing these climate changes...

I should also point out that as a consequence of these climate shifts, resource extraction and land transformation, well over 50% of my natural sound archive, recorded since 1968, comes from habitats that are now either altogether silent, or where the biophonies can no longer be heard in any of their original form. For the past 25 years I have been seeking an academic home for this precious archive. It contains soundscapes most of us will never experience in the wild, again.

Then, do you defend the theory that climate change is caused by human activity or do you think that, despite the consequences of the obvious increase in CO2, the natural climate cycles are more relevant?

Based on the science I’ve read, and the many trips to remote places I’ve visited on the planet, I can imagine no other explanation for what is transpiring everywhere. We are a stubborn, illiterate, selfish, and greedy lot. And as long as we are driven to consume at the rate we do, with no limits on the degree of our avarice, my optimism fades. I’m still hopeful. Just not optimistic.

And, what do you think has contributed more to the disappearance of species: noise, pollution…?

Species disappear mostly because of our unbridled need to exploit the remaining resources of the earth for objects we simply don’t need. It is justified in many quarters by biblical mandates that have always been short-sighted and pathological to begin with. Those unfortunate echoes guide us even and especially today, despite all of the evidence screaming at us to cool it if it is our intent to thrive.

What is our culture losing by distancing itself from natural sounds?

In the end, before the forest echoes die, we may want to listen very carefully to the diminished but remaining voices of our world. We’ll quickly discover that we humans are not separate. Instead, we’re a vital part of one fragile biome.

How many of us will hear the message in time?

The whisper of every leaf and creature implores us to cherish the living world around us – which, indeed, may hold secrets of love for all things, especially our own humanity. This divine music is fast growing dim; the time approaches when we may have to bear witness as the creature spirits return for one final hunt.

What is the sound that has made the greatest impression on you?

It is actually a class of sound called the dawn chorus. Each spring season, in still-healthy regions of the world, birds tend to populate biomes in large numbers, competing not only for physical territory and mates through their extraordinary songs, but also for acoustic turf. The organization of these collective voices, which, by the way, also include insects, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals, is called the biophony. Graphic illustrations of these biophonies are called spectrograms. And when the soundscapes are healthy, the spectrograms look much like a contemporary musical score. The collective voices of these organisms evolve to occupy special niches so that they stay out of each others’ way. Otherwise their voices would be masked. And if their vocal behaviour developed to help these organisms survive, then the signals need to be clearly heard. That, I suppose, is not only my favourite and most important discovery, but it has also made the greatest impression on me. I am amazed every time I visit one of these great places and hear a healthy biophony.

Entonces, segun usted, Are animals able to synchronise their sounds like a large orchestra?

Yes. They have to. Otherwise, there would be bioacoustic chaos. These organisms have evolved to synchronize rhythm, melody, and even arrange their voices in counterpoint. The ways in which their voices coalesce in layers and textures is a form of synchronization. This can be heard in the way chimpanzees and the other great ape species beat out complex rhythms on the buttresses of ficus trees. In the way that frogs and insects synchronize their voices when chorusing.

What would you recommend in order to improve the knowledge and care of the various marine and land habitats?

I guess we need to learn to shut the hell up and get our priorities focused in order to pro-actively protect what remains of life around us.

Through your organization, Wild Sanctuary, you recorded bio-acoustic albums. These recordings have also been used to create interactive environments in museums. Could you explain what this relationship with museums is like?

When I changed careers from music to science in the late 1970s, it soon became clear to me that the publication of scientific papers, alone, meant that only a few people would ever see or hear the results of this work. So, like a few of my valiant colleagues, I decided to reach out to a larger audience through my craft and art.

After the publication of my book, The Great Animal Orchestra: Finding the Origins of Music in the World’s Wild Places, in French translation, Hervé Chandes, Director at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art Contemporain in Paris, contacted me in late 2015. After several encouraging exchanges he commissioned me to create a work of sound art that, instead of performing like background music, would serve as the focus of an entire exhibit and where the visual components would be informed by the sound sculptures. This was a very risky enterprise because there was no precedent on that scale and because every component of the exhibition was imagined, designed and realized literally from nothing. The installation, titled Le Grand Orchestre des Animaux, ran from early July, 2016 to January, 2017 and was one of their all-time most popular exhibitions.

You converts music into art sculpture

It is important to note that sound is not taken very seriously in western culture because we’re primarily visually oriented with most everything that informs us predicated on what we see. This exhibition changed that equation for the first time. The shadow sense (sound), is no longer ephemeral. It has finally found a fragile but seminal place in the hierarchy of the senses and thus, the fine arts.

For me, this experience has been utterly exhilarating. I had become profoundly depressed by what has been occurring in my own country, not only a dismissal of the value of the arts, but also the sciences. And I felt a deep sense of despair. With Chandes’ call and commission, and being able to work with such a dedicated and fabulous group of young people at the Fondation, I felt for the first time in a long while, a real sense of hope.

Bernie Krause in St. Vincent’s Island, Florida (2001). By Tim Chapman.

Bernie Krause: The voice of the natural world

- Bernie Krause: We need to learn to shut up and actively protect our environment" - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

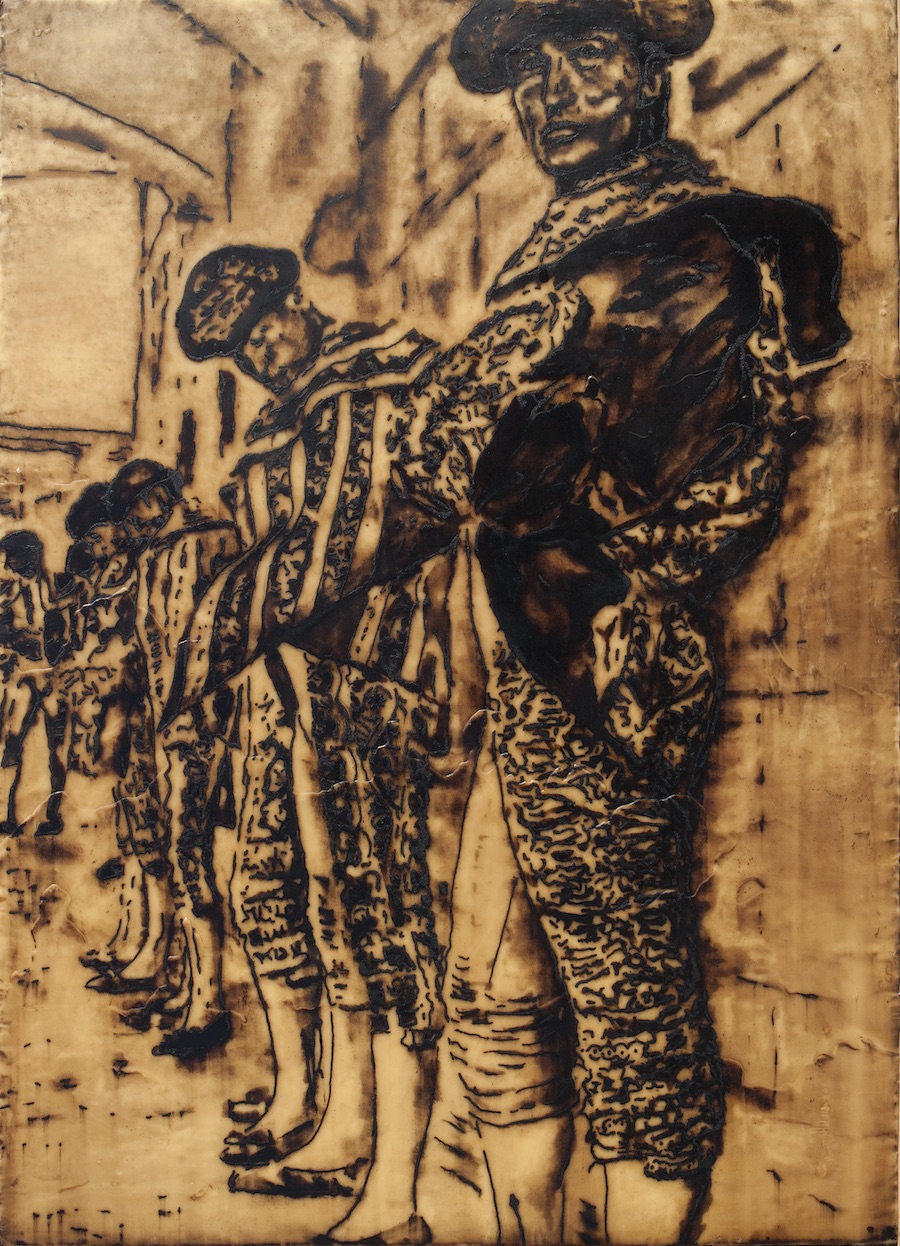

Crossing the threshold into the London home of the musician, composer and visual artist José María Cano, one enters into a sensorial experience. I let the music floating from the second floor guide me to a room where his son Dani was immersed in playing the piano while José María sang Donizetti´s “Ah mes amis”. My presence in no way interrupted their symbiosis, and if anything I was lured into its flow. The scene brought me back to the heights of music José María had reached years ago with the band Mecano, and reminded me of the lyric drama of his opera Luna. Passing by the many works of art that scattered around his home, part of a magnificent collection he has put together over the years, we went into his studio, where surrounded by his own works —his La Tauromaquia and portraits, lining the floor and walls— the artist invited me to begin my interview.

Author: Elena Cué

José María Cano. Photo: Elena Cué

Crossing the threshold into the London home of the musician, composer and visual artist José María Cano, one enters into a sensorial experience. I let the music floating from the second floor guide me to a room where his son Dani was immersed in playing the piano while José María sang Donizetti´s “Ah mes amis”. My presence in no way interrupted their symbiosis, and if anything I was lured into its flow. The scene brought me back to the heights of music José María had reached years ago with the band Mecano, and reminded me of the lyric drama of his opera Luna.

Passing by the many works of art that scattered around his home, part of a magnificent collection he has put together over the years, we went into his studio, where surrounded by his own works —his La Tauromaquia and portraits, lining the floor and walls— the artist invited me to begin my interview.

E.C.: You’ve just had an exhibition at the CAFA Art Museum in Beijing; 200 works gathered under the title Differences and Similarities between Reality and Truth. Tell me about that big show.

José María Cano: I was very pleased with it. Until then, museums had mainly exhibited my wax paintings concerned with economic issues, but that’s only half of my discourse. I felt that knowledge of my work had become lopsided; whereas this exhibition gave balance to its conceptual dichotomy. It’s not that my work has two distinct sides to it, but rather that I paint duality.

E.C.: Is that why you chose this title for the exhibition?

José María Cano: Yes, that’s right. The show was a retrospective of fifteen years of my work. The title, which some people find misleading, is actually the leitmotif of my painting. To my mind, the juxtaposition of the real and the truthful shapes is what carves us out as human beings. My paintings, which on the surface seem to offer a varied materialization, always walk that rickety line. Like when I was a kid. Climbing up to where nobody climbs, to see the world from there. Following the sun, and then the moon, and then the sun again, and only stopping if there was no moon. There’s nothing more seductive to me than the moon in summer or the sun in winter. With eyes opened or shut.

E.C.: Anyone listening to you would think that you live a very relaxed life, when clearly that’s not the case…

José María Cano: But they wouldn’t be completely wrong, in that I work by expression. More than work, I use the John and frame the result. Like Manzoni’s Artist’s shit cans. Even wax, which I like for my painting, is the excrement of bees.

E.C.: It’s true that you move between two almost opposite worlds. On the one hand, there are your paintings on your divorce papers, newspapers or the economy, and on the other, you paintings of a more spiritual nature, such as your series of apostles or paintings about the moon. “Between the sky and the ground,” as your song said.

José María Cano: This borderline way of seeing life lets me paint works from both banks of the same river. On one shore I get my clothes dirty and on the other I wash them. Human beings are a mix of matter and spirit which in the past were in constant, grueling struggle with each other. That battle drove and gave meaning to civilization. Read the poem by Lope de Vega “¿Qué tengo yo, que mi amistad procuras?” (“What have I that my friendship you should seek?”). We’ve now solved the problem by excising from ourselves the spiritual part. Living like that may be easier, but it ain’t worth a dime. Plus, it’s not impossible, with age and a little self-deprecation, to harmonize these two worlds within our selves. But works of art are forced to essentialize. I move steadily from the spiritual to the material, like a mason who stacks layers of brick and mortar, and then wipes away the excess with a trowel.

Wall Street 100 instalation. Beijing Museum. José María Cano.

E.C.: Do you think this view fits in to the current discourse of contemporary art?

José María Cano: No. Today’s art demands provocation, politics, total uniformity or hollowness for it to be of interest to its zoilists and many beneficiaries which, incidentally, include me. My painting lacks these four characteristics. So I won´t deny that my path is a solitary one. Luckily, my gallery is for snipers. Guess that’s why its name is Riflemaker.

E.C.: Your last exhibition was during the Frieze Art Fair Week. Why do you think that your gallery chose to show your work in such a desired week?

José María Cano: You’d have to ask them, but Tot Taylor has said that he values the technique and beauty of my work, and that it is atemporal and without shame. I’m glad that’s what he thinks, because he definitely doesn’t have any either.

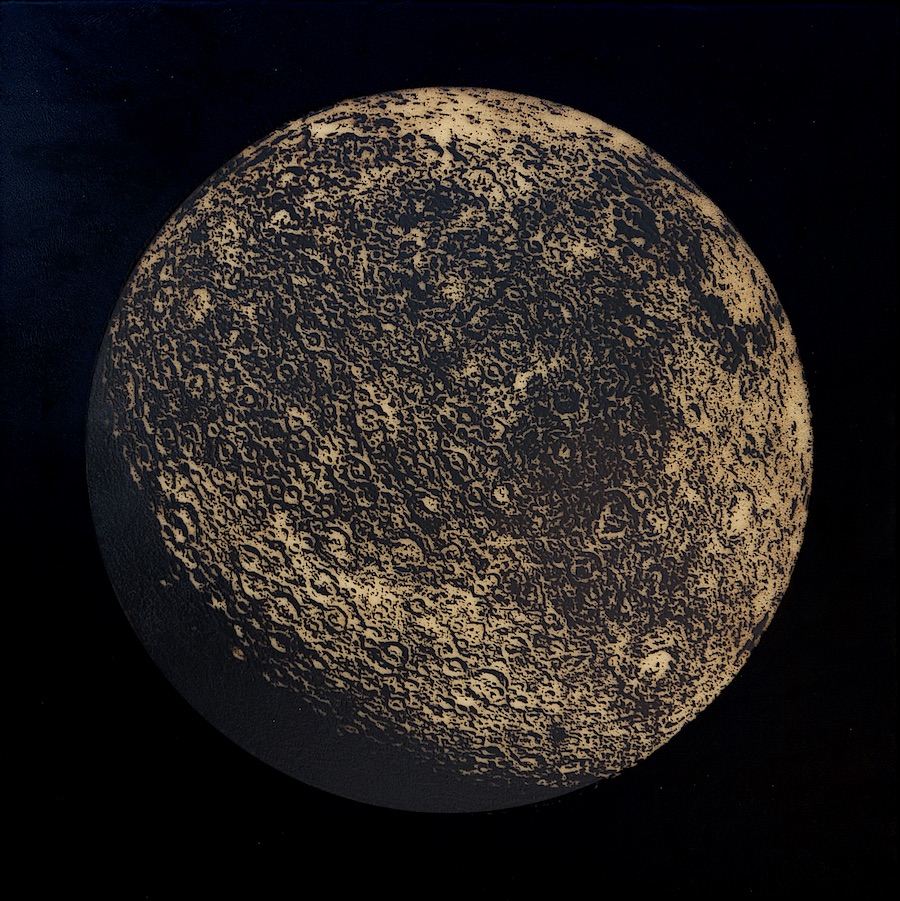

Far side of the moon. Encaustic on canvas. José María Cano

E.C.: I saw the catalog. You exhibited paintings of the moon…

José María Cano: Small encaustic paintings. I was told that it was the most talked-about exhibition in the press during Frieze. For instance, it was chosen as the show-of-the-week by the magazine The Week. The gallery had to extend its hours, and the works were acquired by museums and important private collections. This couldn´t have happened at other galleries, not with such subtle work. My moons were very happy there.

E.C. (reciting a verse from a song written by Cano and performed by Mecano) Hijo de la Luna... Parece que la luna le persiguiese donde quiera que vaya [Child of the Moon… It seems that the moon follows you wherever you go].

José María Cano: That song began with “a fool he who doesn’t understand”. From the ground, the moon is symbolic in character. There being two universes, this one is symbolic. Ever since I was a kid, I’ve been fascinated by the works of Torres García. The moon is a clear indication of the visual dimension of the universe, and of the spiritual dimension of man. It is the recipient of humanity in its entirety’s most beautiful gazes, both living and dead. Sometimes we forget that most of humanity is dead, but it is; in the craters of the moon’s hidden face, perhaps.

E.C.: First a musician and then a painter, and successful as both. Which of these two arts do you think best transmits feelings and thought?

José María Cano: They’re complementary realms. I think that lyrics compel the listener towards a specific feeling. The visual arts are an open proposal to the observer. I like to listen, but I like to touch just as much, and especially to see. To touch things that attract my attention. And to observe them in detail. My paintings have an obscene tactility and I love it when people touch them.

E.C.: You use different media such as oil, resin, encaustic and pigments mixed with different binders. Why do you choose these materials over others?

José María Cano: I’m an alchemist in that “what I paint with” not only determines “how I paint” but also “what I paint” and consequently “what I feel”. The truth is that I paint with anything that lasts. The contrived search for originality is both the great discovery and the great evil of twentieth-century art. Fortunately, it seems like that whole antiquated debate, which is all it ended up being, is on its way out this century.

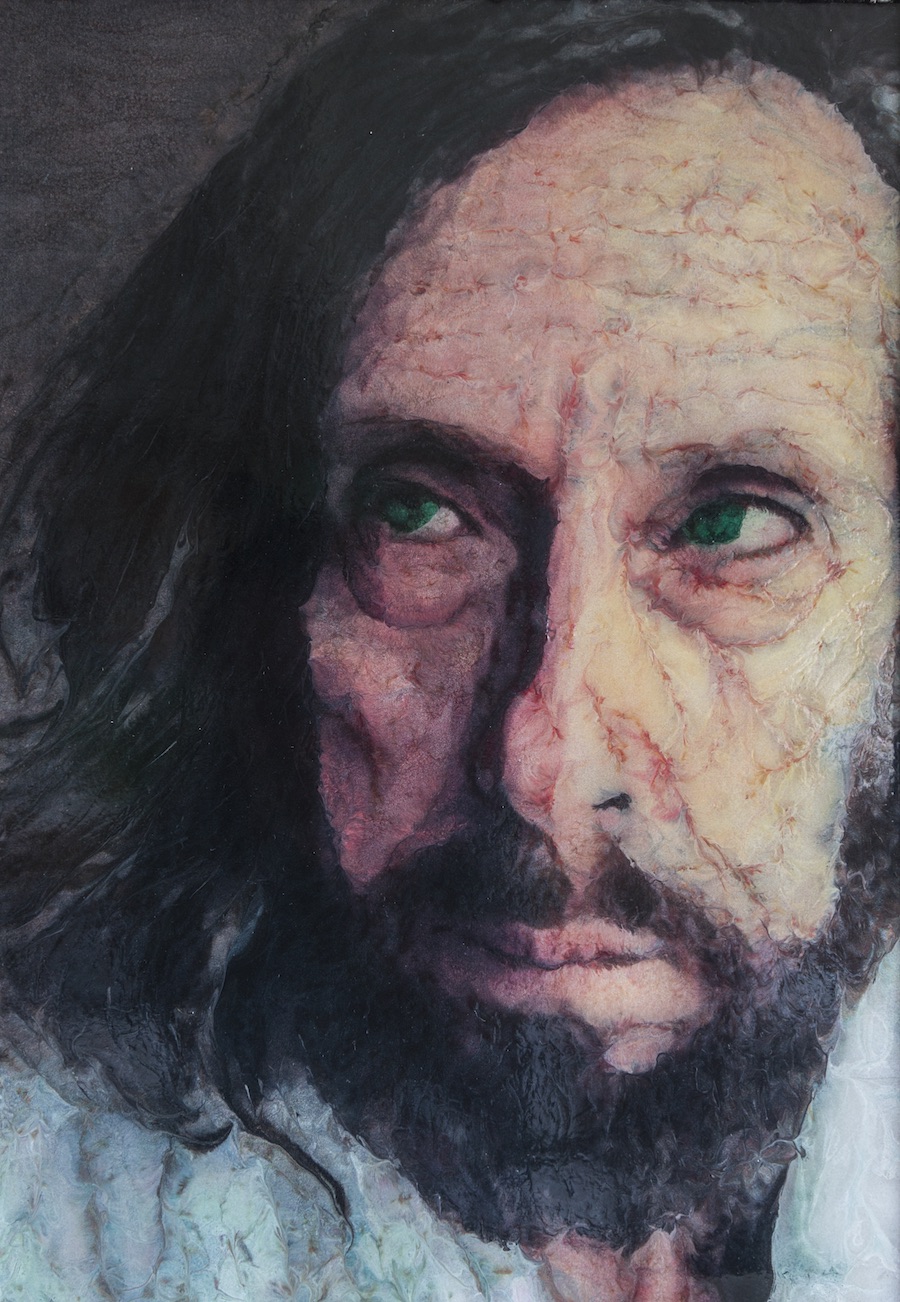

Saint James Bourneges. Encaustic on canvas. José María Cano

E.C.: How did your years studying architecture influence your knack for drawing and painting?

José María Cano: More influential were my school years, prior to University. I went to a Jesuit school. Mr. Paz, the school’s photographer and drawing teacher, encouraged me to attend the Hidalgo de Caviedes academy. Up until then, I hadn´t ever seen a nude woman, not even in a photograph. I swear. And we were almost all guys. Once a week, a model would come and unfurl her anatomy. Very “neoclassical —but really, just plump. There were several of them, all well fed. It revved up our drawing. The reddish light of the furnace lent the scene a certain je-ne-sais-quoi. So, in this mix of hormones and graphite, I learned to draw, happy as a clam.

E.C.: Your close-up portraits strike me as very British, very School of London. Have you been influenced by your 25 years living in London?

José María Cano: I do see them as English, but going back further. To me, they are closer to Van Dyck than to Bacon, Auerbach or Freud. In fact, in their portraits, those painters showed a strong desire for originality that I don´t have. Quite the opposite. My portraits seek the timelessness of the upward gaze. Of spiritual questioning. Of physical peace. If there was something that I looked at as I worked on my apostles, it was the studies of male heads by Van Dyck, who lived in London but was Spanish, like me.

E.C.: You are very well versed in contemporary art and the social structure that supports it. What were your criteria in putting together your art collection?

José María Cano: I don´t consider myself an art collector. In fact, ever since I began painting professionally I stopped buying paintings by other artists. I like paintings as objects, and I like to live surrounded by them. But I don´t feel a sense of ownership towards them, nor much so for the works I paint.

E.C.: In your work, you focus on current affairs such as the defense of human rights, capitalism, prostitution... The titles of your shows at DOX Prague and PAN Naples were Welcome to capitalism and Arrivederci capitalism, respectively. Do you use your art as protest?

José María Cano: I’m not one to protest. Or complain. I began to paint as the leader of a movement with only follower —me— that I called materialismo matérico. That was the title of my exhibition at CAC Malaga. First I painted my divorce papers, and followed that with other works of a chrematistic nature. Figures of the financial world as they appeared in the Wall Street Journal, company financial statistics from the Financial Times, etc. But not as protest. I accepted these figures as the new beauty, ironically. And as an artist, as is customary, I felt compelled to pay tribute to such beauty by reproducing and magnifying it.

La Mirada. Encaustic on canvas. José María Cano

E.C.: You’ve made a series of bulls, a very Spanish theme. How important are your roots to you?

José María Cano: My series of bulls is actually called De providentia and addresses the relationship of man to his destiny. It´s the title of a letter from Seneca to his disciple Julius, in response to his question of why bad things can happen to good people. Seneca answers that this only appears to happen. That water and oil don’t mix and that these challenges are opportunities for the brave man to demonstrate his greatness. In my ring, the bull represents mankind and the bullfighter, destiny. The right way to face destiny is not to hook into it and lift it off its feet. It’s to bravely charge right at it. And patience, of course, because the bad thing about providence is that it’s fricking slow.

José María Cano Apostolate Paintings of the Apostles San Diego Museum of Art with Spanish Golden Age

José María Cano. photo: Elena Cué

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

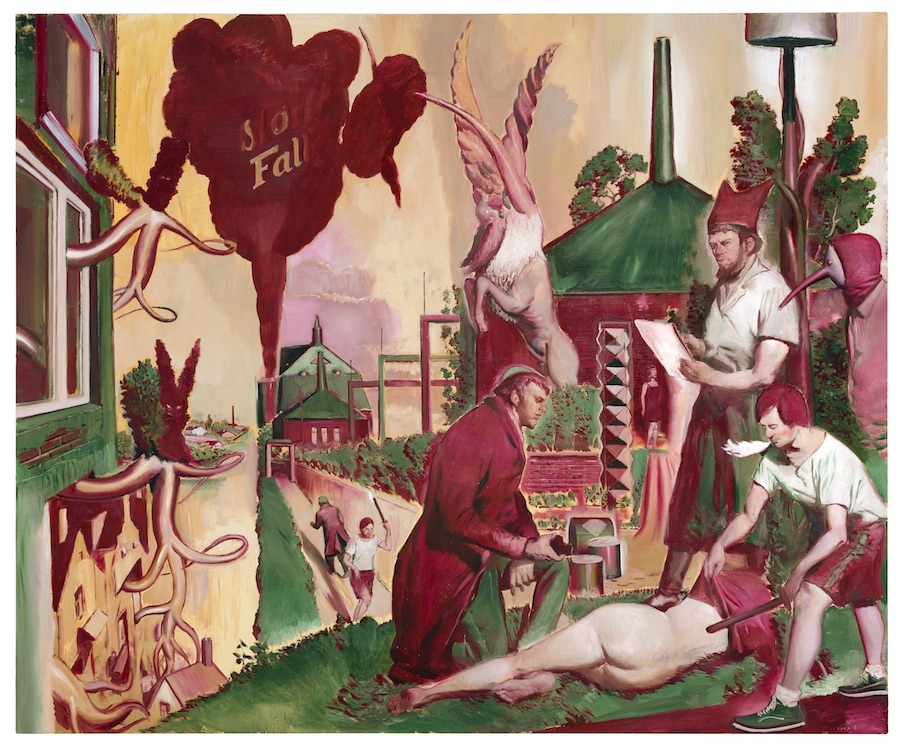

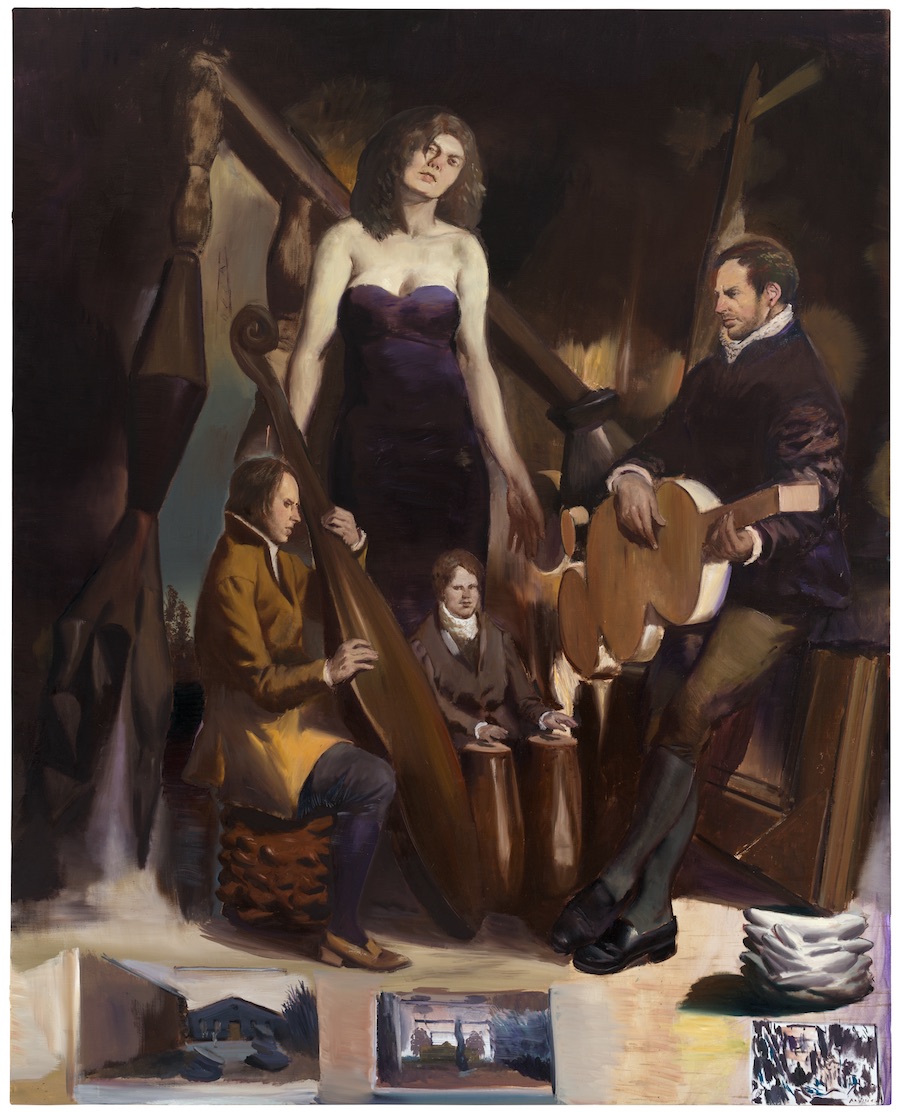

All that lies behind our thoughts ends up ruling our existence as silent forces. Those deepest, darkest places are not easy to penetrate, but if we are attentive to the signs we produce, we can decipher and understand a bit better what we are made of. The dreamlike imagery in the works of Neo Rauch (Leipzig, Germany, 1960) is laden with symbolism: the overlapping of apparently unconnected scenes, abrupt perspectives, a variety of subjects and pictorial techniques… Neo Rauch was born barely a year before the raising of the Berlin Wall split his country in two and confined him to East Germany, circumstances that shaped his early years leading up to Reunification in 1989. As an artist, his education was rooted in modern German painting, in the tradition of the Leipzig School led by Arno Rink and Bernhard Heisig.

Author: Elena Cué

Neo Rauch - Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Uwe Walter.

All that lies behind our thoughts ends up ruling our existence as silent forces. Those deepest, darkest places are not easy to penetrate, but if we are attentive to the signs we produce, we can decipher and understand a bit better what we are made of. The dreamlike imagery in the works of Neo Rauch (Leipzig, Germany, 1960) is laden with symbolism: the overlapping of apparently unconnected scenes, abrupt perspectives, a variety of subjects and pictorial techniques…

Neo Rauch was born barely a year before the raising of the Berlin Wall split his country in two and confined him to East Germany, circumstances that shaped his early years leading up to Reunification in 1989. As an artist, his education was rooted in modern German painting, in the tradition of the Leipzig School led by Arno Rink and Bernhard Heisig. Rausch creates his figurative works from a blend of influences and in an abstract-surrealist vein with traces of Socialist Realism. His works are in some of the most important museums around the world.

As I was admiring his recent works on a visit to the David Zwirner gallery in London, I noticed that the painter was present and resolved to ask him for an interview, which he accepted with a penetrating glance and few words.

Which artists from the Leipzig School were your models, and how did Socialist Realism influence your painting?

When I finished my studies, the idols of the Leipzig Academy were Max Beckmann, Lovis Corinth, Karl Hofer, Salvador Dalí and Otto Dix. This means that, as far as the parameters of figurative painting were concerned, the training we received was distanced from ideological precepts. In other words, in the 1980s, Socialist Realism had long stopped being a unifying concept. The generation of our professors had already succeeded in shedding that paradigm. Strong individualism took its place, whereas a critique of the social circumstances of the time was more or less veiled.

ZUSTROM. Gallery Eigen+Art, Berlin/Leipzig and David Zwirner Gallery, New York/London. Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin. VG Bildkunst

How was your work affected by the socio-political events that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the opening to the capitalist world? What were the most important changes in your life?

By that time, I had been able to seal off my artistic production from current political events, which could only filter in to my works –if at all– in homeopathic doses. When Werner Tübke was asked how he had experienced the arrival of the Red Army in 1945, he answered: “I was sitting in my garden painting wallflowers.” I was so busy at that time finding myself in my work that the major upheaval caused by political and social situation could only have been processed in my work as a very mild aftershock. The greatest change in my life came with the birth of my son in 1990. That’s when I crossed over into greater responsibility, but at the same time it offered me the chance to embrace child-play once again.

And all children dream of comics. One of the more disconcerting elements, as such, in the mixture of styles in your work is its references to comics. Why do you introduce these Pop symbols?

Comics provide figurative painters with a reservoir of raw materials of a very special kind. These reserved materials can be integrated as vivifying elements in the various successions of the “evolution of the classical image”. It is material that has not been worn out, that is innocent and above all that speaks to the child inside the painter, and keeps that child alive.

And the unconscious is another endless stream of raw material that has a strong presence in your compositions. Space and time lose their properties, making way for a dreamlike, otherworldly perception...

The unconscious is a never-ending source of imageries that seem to just be waiting to reveal themselves in my paintings. It’s an area where things are still all jumbled together and don´t have specific intentions, material that the painter is allowed to configure at will.

VERSENKUNG. Gallery Eigen+Art, Berlin/Leipzig and David Zwirner Gallery, New York/London. Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin

Is painting then a way to bring order to your thinking? Do you feel a strong need to communicate?

When I paint, I don´t think, and instead I surrender myself completely to my feelings and to what the canvas demands of me. To me, this means bringing order, not to a mental space, but to the space of the unconscious. As a painter, I try to systematize the irrational, and to do that in painting after painting. This process is not easily reconciled with communication as it is most commonly understood.

And that leads to the disorder in your scenes and an obvious fondness for chaos. Do you understand the world you live in?

In my darkest moments, I feel like I might understand it. This means that its acting mechanisms come to light in an uncensored, open fashion. Thank God there are also moments of clarity, when lighter and apparently unrelated things swirl around me and awaken in me a fundamentally poetic spirit.

The absurd, the nonsensical, the mixture of sensations such as fear, the search for safety, melancholy, solitude... Like Calderon de la Barca said, “life is a dream, and dreams themselves are only dreams.”

I dream, therefore I am; or in the words of Hölderlin: “When we think we are beggars; when we dream, we are kings”.

DER STÖRFALL. Gallery Eigen+Art, Berlin/Leipzig and David Zwirner Gallery, New York/London. Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin

Some old masters are clearly present in your paintings. Can you tell me which ones have influenced you the most?

The most important influences are the ones I came into contact with after 1989, and on my first trips to Italy, where I experienced Giotto’s frescoes in Assisi as a kind of call to order, and Giotto seemed to guide me away from the confusion of semi-abstract doodles. Before him, there was Francis Bacon, an essential guide towards pictorial freedom and an enterprising spirit in terms of creativity beyond all academic restraint. Lastly, I should also mention Piero della Francesca, Tintoretto, Velazquez and Balthus.

I find many Old and New Testament symbolisms in your painting. How important is religion to you?

That is the main question. How do I see religion? Well, the symbols in my paintings are more likely extracted from the collective subconscious, or if you prefer, the Akasha –that ethereal undercurrent that links us all and carries everlasting images. Of course, both contain the pictorial materials of the sources you mentioned, even though I may not address them in a conscious manner. I would define myself as an atheist with occasional bursts of pantheism. As a painter, what matters to me is irrationality as a reservoir of inspiration. As someone living in the present times, however, and as a witness to the irrational events of religious origins that have taken place, I am determined to seek out my salvation in the ideals of the Enlightenment.

TIEF IM HOLZ.Gallery Eigen+Art, Berlin/Leipzig and David Zwirner Gallery, New York/London. Photo: Uwe Walter, Berlin