- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

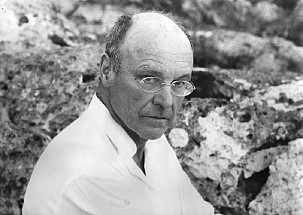

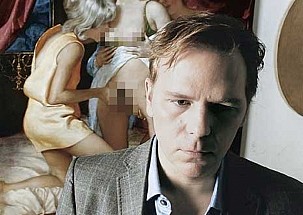

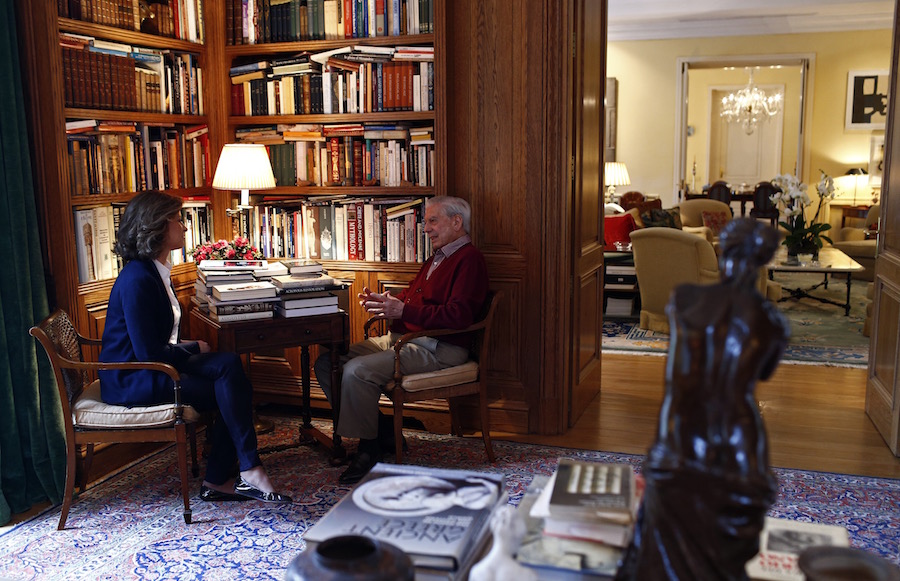

Courage, that virtue exhibited by some mortal beings, is what I would highlight about the Nobel Prize for Literature Mario Vargas Llosa (Peru, 1936). The writer is devoted to any number of activities with a discerning spirit. Destined to live a disciplined life, as a life of literature demands, he does not hesitate when circumstances require him to take action; for example, when he presented his candidacy for the presidency of Peru in 1990. At the time he believed his moral duty was to become an active participant in public life and, as a democrat, to denounce authoritarian governments wherever they may be found. Or when he went on stage to act for his love of the theatre and, in short, so many other things one might mention… Working in his study, surrounded by books, I am greeted by the Nobel Prize winner, who raises his head upon my arrival with a smile and that pleasant tone of voice of the people of Lima. How are you?

Author: Elena Cué

Courage, that virtue exhibited by some mortal beings, is what I would highlight about the Nobel Prize for Literature Mario Vargas Llosa (Peru, 1936). The writer is devoted to any number of activities with a discerning spirit. Destined to live a disciplined life, as a life of literature demands, he does not hesitate when circumstances require him to take action; for example, when he presented his candidacy for the presidency of Peru in 1990. At the time he believed his moral duty was to become an active participant in public life and, as a democrat, to denounce authoritarian governments wherever they may be found. Or when he went on stage to act for his love of the theatre and, in short, so many other things one might mention…

Working in his study, surrounded by books, I am greeted by the Nobel Prize winner, who raises his head upon my arrival with a smile and that pleasant tone of voice of the people of Lima. How are you?

Elena Cué: Why don’t we begin by talking about your latest novel, Five Corners, to be presented tomorrow? What does this novel mean to you at this time of your life and your literary career?

Mario vargas Llosa: Well, this novel, as practically all the stories I tell, came about in a way that is very mysterious to me. I had an idea, which was to tell a story about yellow journalism, that is, sensationalist journalism, which I believe is one of the hallmarks of our time. I think yellow journalism is something that appears everywhere, in the underdeveloped and developed worlds alike. And it is a kind of journalism that played a significant part in the Fujimori dictatorship, when the regime used the sensationalist press to intimidate the opposition, to try to tackle opponents with the threat of a scandal –a scandal that had nothing to do with their profession, but with their private lives, and which so often consisted of merely artificial fabrications, slanders to smear and discredit them. This was systematically used by the dictatorship against all its detractors.

The book begins with an unconventional erotic situation…

I think that it is the treatment of what is erotic which determines whether the erotic is elegant or vulgar, subtle or crude. It is the treatment, the words, the way the entire scene is conceived… In and of itself, eroticism entails a certain amount of civilisation. I think that in a primitive society or people there is no eroticism. Sex is the venting of instinct. In sex the animal component prevails over sensitivity, over the formal component. Eroticism is born at a time in civilisation when sexual instinct becomes deanimalised and enriched with contributions from art and from literature. A world of theatricality emerges around the act of love. And this is eroticism. When this is degraded or debased –due to poor performance, ineptitude, the lack of skill of whoever describes or depicts it– pornography then appears. But I think that eroticism has to do with civilisation, with a concern for social mores, with a certain culture, which is what really sublimates pure sexual instinct.

Then we must speak of Freud… Do you agree with the concept of sublimation of sexual desire as artistic creation?

Yes, without a doubt. I think he was very right about this, and I also think he was very right about sex being a primordial function of life. But it is neither excluding nor exclusive. When, for instance, in literature and art in general, sex prevails in such a way that it manages to obliterate the rest, it becomes something very artificial, something that does not truly represent what real life is. I don’t think that the perspective of sex is essential to understand everything. Psychoanalysis went this far, Freud went this far, but we must take a step back from his genius, which is indisputable.

Can the imagination sublimate an erotic experience in such a way that it surpasses the actual experience itself?

I think that the imagination, sensitivity and culture can enrich the erotic experience in an extraordinary manner, but to go as far as to exceed reality, I think not. Reality is the richest thing there is, the most important thing there is. Our imagination allows us to live an artificial life that is wonderful, extremely rich, but I don’t believe any artist would dare to say that artifice is better than real life.

Photo: Oscar del Pozo

Have you ever been surprised when you have re-read what you’ve written and wonder how it was you who produced it?

Yes, I am always surprised when I write. I would go as far as to tell you that the most exciting and most stimulating moments when writing a story happen when sudden things emerge. For example, in Five Corners, there is a character who, when I created him, was going to be a relatively minor one, a sort of secondary character. However, as has been the case on other occasions, this character started to gain strength, began to grow larger as I developed the story, as if, on his own initiative, he had decided to take on an increasingly important presence. I believe that these are the most fascinating moments. Suddenly a character comes to life…

And what barriers do you have to overcome in your creative process?

Well, perhaps the greatest one is lack of confidence. You know, contrary to what one might think, the fact that I spend a lot of time writing, or that I have published many books, does not give me confidence: on the contrary, it increases my insecurity. Perhaps because due to greater self-criticism or perhaps greater ambition. But the insecurity I feel when I begin a story, whether it is a novel, a play or even an essay, is much greater than when I wrote my first works. However, I know that with the help of perseverance and constant work, I can defeat that lack of confidence.

I assume that for a writer, writing is a way of life. You observe and analyse everything in a different way to the rest. Where do you think these differences lie?

Your question refers to an expression that is similar to something that Flaubert wrote, which was “writing is a way of living”. I believe that this is totally accurate. Although the way it is done varies from writer to writer, of course, I do believe there is a kind of dedication, of devotion, that means the writer also carries a kind of spy within him who, while experiencing –taking part in real life, with friends, lovers, frustrations– there is someone within who is watching it all and deciding how it might best be used in his work as a writer.

In your case, what has proven more fertile for your literary inspiration: suffering or happiness?

I think it is wonderful to experience happiness. I do not think it is a raw material, at least in our time. Perhaps in the past, during certain times; but in our time literature, art, creativity are sooner fired by adversity, negativity, fear, pain, resentment, suffering, than by enthusiasm, excitement, happiness… I think this is why the art of our time has a somewhat dramatic and tragic slant. It is not an art or a literature of contentment, of acceptance of the world as it is. On the contrary, I believe that there is a very strong rebellious spirit in all manifestations of the art of our time and this is basically because it is fundamentally much more inspired by what is negative than what is positive in life.

Perhaps artistic creation is a way to mitigate pain, a way to channel negative emotions…

Exactly, a way of expressing a kind of frustration of resentment or even nostalgia for something you do not have.

And can one get to feel that release through whatever artistic language: painting, writing?

Art is a form of knowledge. Art helps you get to know the life you live in a deeper, much more intense way, because there is usually little distance with the life one lives. But art provides you with that perspective, that horizon, which enables you to understand the world as it is, the drivers, the mechanisms lurking behind behaviours. This description of a secret reality is what art provides, much more than history, sociology and any other social science.

And can one feel that release?

In the end it feels, indeed, like a catharsis. You unburden yourself from what seems like an enormous weight. But you only discover what it is and what is looks like when you are able to express it, via literature, painting, music or any other creative manifestation. You can feel really bad but you don’t know why. And I think that one of the wonders of art is that is enables you to articulate that which is uncertain, confusing, a source of terrible angst. But how wonderful when you see that art gives it a shape and makes it communicable. Many times that sensation, those moods… you don’t know where they come from. One suffers from these moods, but one lacks a deep explanation for them. And I believe that this can only become clear when literature or art allow you to stand back and to appreciate life with all your feelings, instincts and intuitions. I think it is one of the main roles of art: to portray that which is the deepest, the most secret within us.

Then you have succeeded, perhaps, in getting to know yourself by expressing yourself –probably that which you say you don’t know what it is, that comes from the subconscious, in a non-instinctive manner– and have been able to recognise it later.

Sometimes you are surprised and others you are frightened. You ask yourself: “Was that inside of me? Did I have that inside? Where did that come from?”

Of course “this comes from me?”

Works of art are secret autobiographies. And perhaps literary works more than any others, because they are so explicit, so direct. They are not as symbolic, like music, for instance. It is also autobiographical, but so much more abstract. Literature is not at all abstract; it is very explicit, very concrete. It is an x-Ray of the human interior, human nature, the human condition; and one can be horrified at the monsters that emerge from within. But they have a cathartic function, and you are liberated from them at the same time.

It is a very healthy way to live. As an agnostic, where do you find the spirituality that religion brings to believers?

I think I find it in culture, in art, in literature. A kind of spirituality manifests therein. It is something that extracts from you that spiritual dimension that others only find in religion. But I believe that an agnostic does not necessarily have to be a materialist in the strictest sense of the word. You can live an intensely spiritual life through art, through culture, or through having a secular spirituality. Every agnostic has a certain anxiety when faced with that unconscionable thought of: “well, this is all there is, and when life ends all else ends”. It becomes extraordinarily strange and surprising like the idea of God, like the idea of life after death. It is very difficult, using only reason, to think of the afterlife, to think that there is another dimension…

Talking of the idea of death, how can literature fight against thoughts of death?

One of its extraordinary powers is that it allows us to live many lives. It takes us out of our reality and makes us live extraordinary realities, rich lives, adventures out of this world, makes us take on so many personalities, psychologies, mentalities… it is an extraordinary enrichment of life. However, at the same time, literature is not a guarantee of happiness; on the contrary, in some way, it renders you much more unhappy because it makes you understand there are many lives that are richer than your own. You become aware of your insignificance.

Photo: Oscar del Pozo

You have many childhood memories. Is childhood remembered or reconstructed?

Well, I think that one remembers in a relative way, because memory is very tricky, very selective. Memory erases or adds many things, because this helps you to live. I don’t think memory is absolutely objective, but I do believe that it is faithful to what you are, because even the transformations, the deformations that nostalgia or fantasy inflict upon memory are also a portrait of what you are, what you lack, what you would like to have but do not have… This exercise of memory, at least for a writer, is fundamental. In fact, Freud said that the years that form a personality can be found in childhood, in adolescence.

What has love meant in your life?

Love is, like literature, something that enriches life in an extraordinary way. I believe that it is difficult to communicate. Love is something that is lived in privacy. And that relationship, which is so intense –probably the richest relationship between human beings– at the same time requires great intimacy, requires a kind of confidentiality to be preserved, because when it becomes public it deteriorates, it becomes banal, does it not? But it is the most enriching experience there is. Everything is different when you live a great passion: things are better, everything is more beautiful, you face life with optimism, and only love gives you this. It is the fundamental experience, the most enriching and, at the same time, the source of great suffering, of course. Tragedies come from love, from unhappy love. The idealisation often made of the relationship often clashes with reality. But even so, I think no one would be willing to give up on love, despite being aware that love also has traumatic –sometimes terrible– consequences. But nobody gives up on it. Because to live that experience is to live the experience of all experiences. The fullest, the most intense, the most absolute.

And what is the meaning of love at your age?

I think that love has little to do with age. Well, the love of a young person is more idealistic, more innocent. The love of an adult, of an elderly person, naturally, is a love made up of lots of accumulated experiences, it is lived with more wisdom, with a better knowledge of reality. But aside from these differences, I believe that the elation, the joy, the feeling of optimism in life that love gives you is exactly the same as when you are a teenager.

Let’s speak of you book “The Civilisation of Spectacle”. Do you think that high culture no longer aspires to change the world?

Well, what I think is that high culture is disappearing. This, I believe, is an alarming tragedy –which is one of the reasons I wrote this essay– as high culture is, thus, naturally elitist. It is something reserved for a minority, and it is very naïve to think that high culture is accessible to everybody. Not everyone has the interest, the curiosity, the patience or the discipline that high culture demands.

On the other hand, the idea of culture being within reach of everyone is a good one. Who could possibly be against this? However, at the same time, if this means –and, unfortunately, in our time, it has led to this– that culture, in order to be accessible to all, needs to become trivialised, impoverished, and become but a pastime, a form of entertainment, then the result is clearly highly negative.

And I believe that this is a great flaw in the education of our time. The education of nowadays does not preserve high culture, but regards it with contempt. The art of creating or of thinking requires looking back into the past, because the present paints a fairly barren landscape in this regard.

Do you think that cybernetics have contributed to this desertification?

Without a doubt. Intellectual effort is gradually diminishing, because technology helps us give up making such an intellectual effort.

What role do you think intellectuals should play in current political life?

Look, I belong to a generation that was highly influenced by the ideas of existentialist thinkers. And although in many regards I have moved away from Sartre and am very critical of his work, I believe that his idea of the writer’s or the intellectual’s commitment to his time, to his reality, to his society, was absolutely correct. One cannot write, or paint, or compose by dispensing entirely with the problems of the world one lives in; and it is fundamental –particularly, if you believe in democracy– that everybody participates in the search for solutions to the problems: for answers to the great questions asked by society, in order to create a system where one can co-exist with all others, with one’s differences, ways of being, one’s own desires…

This is fundamental and, furthermore, I believe that true literature, true art, must address this situation. The main problem is that, nowadays, ideas are less important than image. I believe that pure technology is not enough and that the presence of ideas in public debate is paramount for our understanding of human issues. But in our time this seems to have been relegated and replaced by screens and pictures.

Because less effort is required.

It requires much less effort. But I don’t believe it should be this way, not at all. There is no historical law steering society in that direction. It is our decision. I think that, despite the importance of technology –this is undeniable–, it is necessary for ideas to continue to play a leading role in the life of societies, unless we wish to become a society of robots. I shall refer once again to Orwell, who was so insightful in imagining a world completely controlled by technology, a dictatorial world. Like The Republic of Plato, don’t you think?

Photo: Oscar del Pozo

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

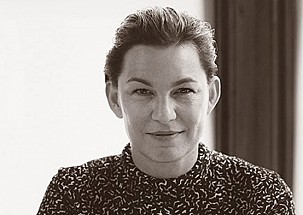

Luminosity, symmetry and proportion are some of the characteristics of the classical concept of beauty found in the photographs of Candida Höfer (Eberwalde, Germany 1944), to which she adds the existential determination of silence. Her first series in this particular genre depict the ordinary streets of Liverpool and the Turkish communities in Germany and Turkey. From there, Höfer’s work quickly evolved to what are now her most recognizable photographs of the interiors of museums, theaters, libraries, churches, etc., where a stillness that is devoid of time and human presence, and which thus immerses us in silence, also induces the concentration we need to appreciate the spatial vision and beauty of her images. Höfer is a product of the prestigious Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where she studied photography under Bernd and Hilla Becher, as did other artists such as Thomas Struth, Andreas Gursky and Thomas Ruff.

Author: Elena Cué

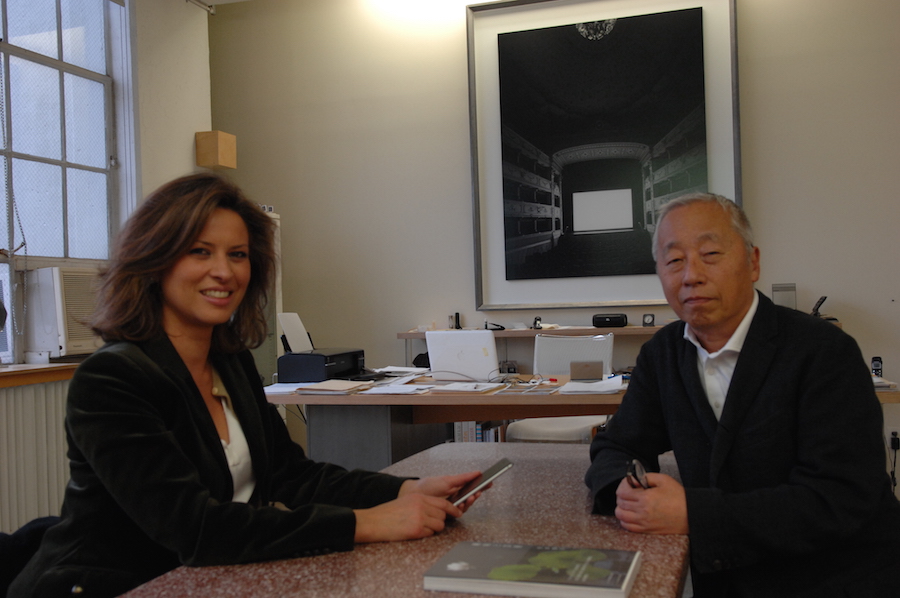

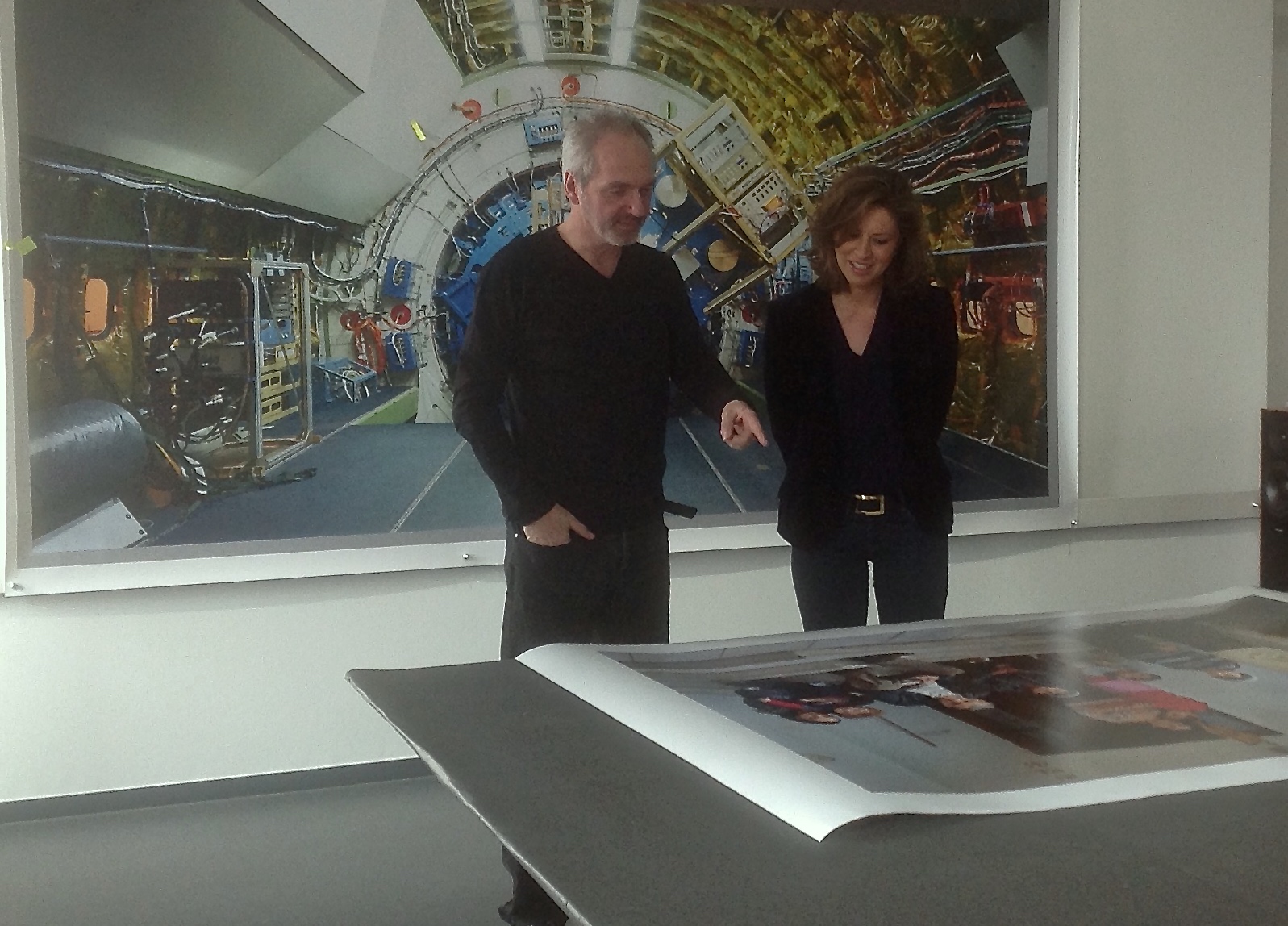

Candida Höfer. Photo: Elena Cué

Luminosity, symmetry and proportion are some of the characteristics of the classical concept of beauty found in the photographs of Candida Höfer (Eberwalde, Germany 1944), to which she adds the existential determination of silence. Her first series in this particular genre depict the ordinary streets of Liverpool and the Turkish communities in Germany and Turkey. From there, Höfer’s work quickly evolved to what are now her most recognizable photographs of the interiors of museums, theaters, libraries, churches, etc., where a stillness that is devoid of time and human presence, and which thus immerses us in silence, also induces the concentration we need to appreciate the spatial vision and beauty of her images. Höfer is a product of the prestigious Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where she studied photography under Bernd and Hilla Becher, as did other artists such as Thomas Struth, Andreas Gursky and Thomas Ruff. Her photographs of architectural interiors in Europe and America follow the example of the Bechers’ images of industrial exteriors.

Elena Cué: Between 1973 and 1982 you studied at the prestigious Kunstakademie of Düsseldorf where you attended the lectures on photography by Bernd and Hilla Becher. What was the most important teaching you took from that period?

Candida Höfer: Bernd and Hilla's teaching did not come across as teaching in the traditional sense. Both invited us to be open to experiences, to cherish Art in general, not just restricted to photography, to keep our eyes open, to discuss, to remain politically aware.

Does your great interest in architecture also coincide with that period?

In my project about Turkish people living in Germany I had realized that no matter how kindly I was received I felt uncomfortable to intrude. At the same time it was impressive to see how my hosts had created their own environments in their restaurants, shops and living spaces to feel more at home from home. It showed me the importance of the made environment.

In the series you just mentioned, Turks in Germany as well as in Liverpool and Pinball that were some of your first works, you were focusing on portrait photography. Later you abandoned the inclusion of human figures in your works. What did portraits mean to you?

I see my work to some extent as portraits of spaces; this is also why I consider myself not to be an architecture photographer; they would focus on other things.

Candida Höfer. Rudolfplatz Köln I, 1975/ 1999. Aus der Serie Türken in Deutschland. Silbergelatineabzug

What made you abandon black and white photography in order to focus on the use of colour?

I tried color photography and compared the results and found color to provide more for my kind of work.

What meaning does the format add to the message of your works?

I think, with regard to my larger format works light, structures, formal repetitions and variations as characteristics of a space are in the center of my interest. As to the more recent, smaller works I examine these elements in a more abstract way.

Teatro Scientifico Bibiena Mantova I, 2010 © Candida Höfer / VG Bild-Kunst,Bonn 2014.

You combine the two ideal concepts of knowledge and beauty. Would you say you have an unconscious strive for perfection within you? Are you a perfectionist?

... an impatient perfectionist, I am afraid. The large formats need much organization and preparation due to the larger camera format. This is one of the reasons why - while still continuing with my large format projects - I am increasingly now using a hand-held camera for the smaller more abstract works to enjoy the freedom from the restrictions of organization.

The technology available to photographers today is constantly evolving; Do you make use of this progress?

I keep an eye on developments, and I get information. I am not technology averse, but I also feel not technology driven.

In your architectural photographs in which people do not feature, this absence is very present due to the necessity of the relationship between people and culture. Did you do this because you did not want any distraction when contemplating your ideal spaces?

The necessity that you are mentioning gets more visible by absence. What I had started as an approach to avoid bothering people while I am working did turn out as a learning process about the presence of the absent.

In your photographs what is most important: the aesthetic, the technique, the idea...

The image.

What is image for you?

I try to give an answer with my images.

What would you say is your most passional moment in your creative process?

Working with the picture taken to turn that picture into an image.

The prominent motifs of your artistic career are the interior spaces and their functionality and the architecture. What can you tell us about your "Psychology of social architecture"?

I am primarily interested in visual relationships within each singular space and the layers of use visible in that space. If over time my aggregated work contributes to broader insights, then that happens so to speak behind my back.

"Palais Garnier Paris XXXI 2005". CreditCandida Höfer/VG Bild-Kunst, via Sean Kelly Gallery

Your photographs posses social, geographical and historical singularities that endow them with character and contrast against a globalized world. Do you feel nostalgia of perfection in art, of the old aesthetic values, of the aspiration to escape vulgarity...?

I think in front of the photographs in their original size (rather than seeing them in a book) what might come across even in the historically charged spaces is the sincerity and clarity and sometimes also the humor of the space that do not invite nostalgia but just show the strength of the present in the space.

In your series Libraries, what is the importance of books to you as the daughter of a journalist?

Books are not only interesting to read but their physical presence, particularly when they are present in large quantities, their order and variation in colors and form I have always found visually attractive as well.

Your exhibition “ The Space, the Detail, the Image" just opened in Helga de Alvear’s Gallery. Could you tell me about it?

As the title indicates I want to show and set in relation my treatment of large spaces, the smaller, more abstract and detail oriented work and projections under the common denominator "image." My very first gallery work (in Dusseldorf in the 1970s), as you may remember, had been a projection ("Turkish People in Germany"). The projection format has always been of interest to me allowing a dynamization of the image without crossing the border to a - for me at least - distinctly different medium, the film. However, the gallery show will also provide an opportunity to show a film not by me, but about the way I work ("Silent Spaces" by the Portugese director Rui Xavier to be shown at the Circulo de las Bellas Artes on 21 January 2016).

Are you looking forward to your next project? Could you reveal any secrets to us?

Upon invitation from my Mexican gallery, I have just spent three weeks in Mexico and I am now working on the material for museum shows both in Mexico and Germany.

- Interview with Candida Höfer- - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

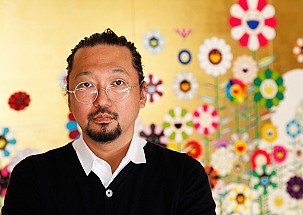

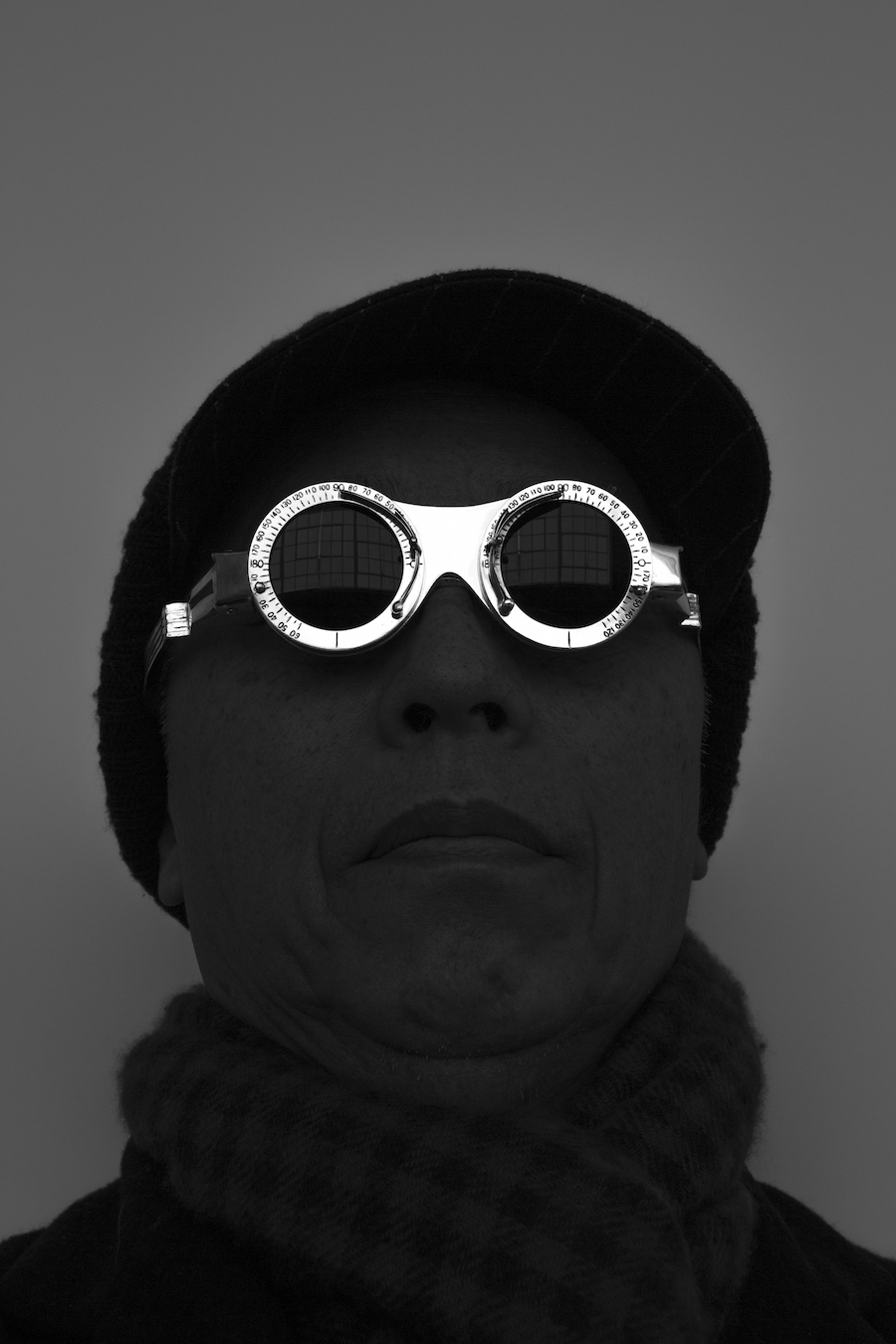

Hiroshi Sugimo's portrait. Courtesy of the artist.

The Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto (1948), is a photographer that resides halfway between Tokyo and New York. He received various awards: The Hasselblad Foundation International Award (2001), The Imperial Award (2009), The Purple Ribbon Medal of Honor (2010), The Officier of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (2013) and the Isamu Noguchi Award (2014).

If anything distinguishes Sugimoto's black and white photographs is its use of natural light, the shadows and the purity of forms, some close to pictoric. Standing in front of many of them, the spectator is encouraged not only to look but also to think; as in his noted marine landscapes, its immutability causes loosing the notion of time. They invite to a constant reflection about the origin and history of the world and of our culture, where concepts like space and time are explored expanding our ways of perception.

Without further ado we begin our conversation in his austere New York studio. Large windows fill with light his office presided by two photographs: Duchamp's bicycle wheel and one of his theaters.

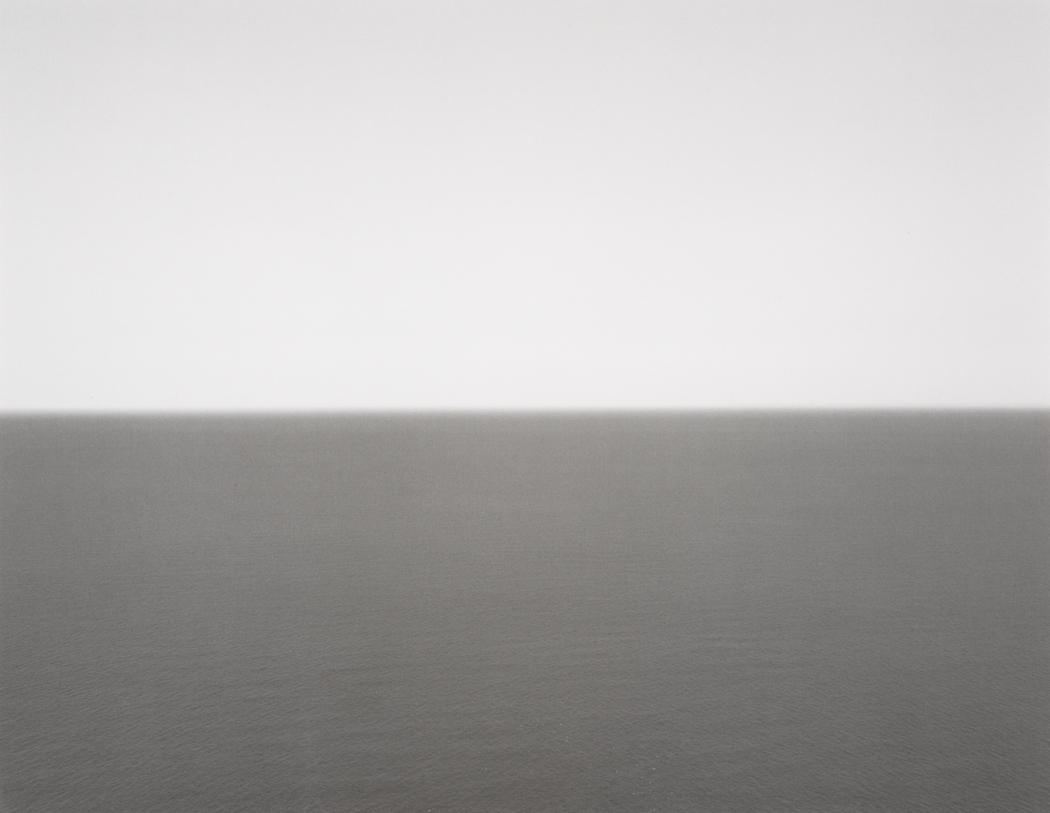

Elena Cué: The seascape picture I just saw in the entrance reminded me of the exhibition you presented in London (in 2012) along with Rothko's paintings from 1969, a year before his suicide, was very interesting. This photographs induce us to meditation...

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Yes, the people spent quite some time in front of my seascapes and I found some kind of similar sensitivity with the Rothko paintings. That is why I put them together. Especially the final years of Rothko - they’re very monochrome and very abstract - and they echoed my special night seascapes.

Adriatic Sea, Gargano 1990. Courtesy of the artist

I remembered how your photographs gained in beauty once their protective glass was removed. They looked just like paintings.

Yes, but they have the price of photographs!

Is Eastern spirituality implicit in your work?

I don’t care whether it’s Eastern spirituality or Western spirituality… There is a spirituality.

You don’t require labels?

Well for marketing, it reaches a wider audience if I don’t use ‘Eastern’ or ‘Western’ spirituality!

Your In Praise of Shadows series is directly reminiscent of Tanizaki. What is the enigma of shadow for you?

I live in the shadow… I like shadow, that’s why I became a black and white photographer. The quality of the shadow says something. And the quality of the shadow is something that I can control… the tonality of darkness to light. Black and white photography is the best medium to show this.

Which kind of light do you prefer to use?

Natural light, of course.

What do you think of the current aesthetic of light, someone like yourself who belongs to a millenary civilization that is antithetical to Western civilization?

Well, Tanizaki complains about modern society with its artificial light. Since humans invented artificial light, our lifestyle has changed. Especially with electric power. With candlelight, there was a more human-friendly atmosphere. Then all of a sudden we have nuclear power and electricity… so then we changed to nightlife. It used to be nice and intimate, and somehow it was the poetic quality of nightlife that we all lost. There is a beneficial side to it, but not that side. We lost so much, instead of gaining some kind of benefit.

Now that we have discussed light, let's turn to emptiness and loneliness. Why, in your Theaters series, is the lighted stage empty?

They look empty but they are full of information. They have accumulated the information of many millions of small photographs that a movie consists of. Before the invention of movies was the invention of photography. To make a movie, you have to sew single-shot photographic images together to make it look like a movie. It is all an illusion to the human eye. So there are many pictures within the white. It’s not empty, it’s too crowded!

Hiroshi Sugimoto. El Capitan, Hollywood, 1993, gelatin silver print, courtesy l’artista

Your work constantly evokes primitive scenes. How important for you is that infancy of the world?

I feel like I’m a stone-age man. I try to go back to the original roots of our mind, of our consciousness, that maybe we lost many thousands years ago – or maybe only fifty or one hundred years ago. The human mentality was somehow different. That’s what Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows is telling us. Again, this is modern societys' negative side and positive side. That’s what I’m trying to save, before it is completely lost.

Hiroshi Sugimoto. Wapiti 1980. Courtesy of the artist

With such beautifully dramatized light as yours (your use of chiaroscuro), to what extent would you say you are a pictorialist?

Pictorialism was a very interesting phenomenon in the late nineteenth century, after photography was invented. Many painters changed their profession to photography. But twenty or thirty years later, there was a fight back from the painter’s side. Also, it was asked whether photography could be art or not. The camera is a machine and the machine has no spirit. So photography makes machine-made paintings. Photographers developed some sort of complex against painters. So the photographer tried to imitate the painter, which is where pictorialism entered photography history. I don’t have any complex, but I’m still trying to be a painter.

Was there a period when you painted?

Well yes, I painted when I was in High School.

But you decided not to continue...

It wasn’t that I couldn’t paint and instead decided to become a photographer; I can still paint, but photography was a new medium for me. So when I was young, I thought that photography held more possibilities for the future, to be used as a new kind of tool to create new art. Painting is one of the oldest mediums in art for the human being. People have tried many different things and there’s too much competition. I wonder whether I could be better than Picasso – that’s the question!

We have already touched upon the exhibition that you recently presented with Mark Rothko in London. You have said that he helped you on your path to abstraction via photography. Could you tell me about that experience?

Well, to compare myself with Rothko is a brave act! I had a sense that we might share some kind of similar mentality or spirituality. Don’t think about the market price; I cannot compete with him! So that was something to almost surprise people with photography and painting’s relationship. What is trying to be represented? That kind of abstract spirit can be shared with the photographic method. And in a sense, I think it was a success. One of my next projects in the near future will show Impressionist paintings together with my seascapes. Because I knew that Monet painted seascapes in Étretat, in Northern France, so I went there and I found the spot where Monet must have painted them. I took the seascape photographs from the same point. Not the landscapes, only the seascapes.

How beautiful!, so this will be your next project. Where will it exhibited?

It is not decided yet, but I am working on it now.

Any future projects in Spain?

In February I will be at Fundación Mapfre in Barcelona. Then in June I’ll be at Mapfre in Madrid, which will be a retrospective.

So that will be a very important exhibition for you.

Yes, it will be my first retrospective in a museum in Spain. Afterwards, it will travel to Brazil in South America.

But you did visit Spain before, I recall your traditional Japanese puppet theatre: The Love Suicides at Sonezaki. What does Bunraku mean to you?

I’m moving more into the performing arts, especially the traditional Japanese performing arts. So bunraku is the one that I’m doing now. I’m trying to remake traditional theatre. Sometimes, the way they perform is not the way that it used to be. The production is from the 18th Century, so I’m always trying to get back to the original spirit. For my production, the lighting especially is not so bright. I have to use artificial light of course, but I’m trying to create an atmosphere of pre-modern traditional theatres. This sense also derives from the kind of quality found in In Praise of Shadows.

Wasn't your father also involved in theatre?

Yes, a different kind of art form - traditional storytelling at the Comédie-Française. Old stories with lots of jokes.

He must have had some influence on you…

My cynical mentality comes from my father!

And what did you receive from your mother?

My mother was a very good businesswoman, a very well balanced person. She was spiritual I think… religious, even. For a long time, she was a Christian. She was sent to a missionary school in her childhood.

And did this change you at all?

I got a sense of what Western civilization is like. I was in a boys' school at Junior High and I was fascinated; I became almost hypnotized by people singing to the Christ. It made me think, ‘Wow, God really exists!’

But later you changed again?

Later I moved to California and then people spoke about Buddha. So I didn’t switch, but I studied Christianity and then Buddhism. They are two totally different branches of spirituality.

Then your work lost part of its Japanese spirituality?

No, even in American people I sometimes find spirituality! I decided to be spiritual, and to keep an equal stance on all religions. The more important issue is about what the origin of religion and spirituality is. Our stage of human consciousness all started with the development of the sense of time and the sense of awareness, which all comes with a religious impact. So it’s all related, and it’s related to my seascapes. To think about the religious mind… why is it when looking at nature or the seascapes, you feel something recall your old memories? Either a personal memory or a memory of humanity.

In your Portraits series of wax figures at Madame Tussauds, there is something reminiscent of those traditional Japanese theatre puppets. Did you choose them: because of their caricature essence, because of the type of character or because of the technique?

When I started, it was really nothing to do with the puppet theatre. I can see the relationship, though. It’s more related to the history of photography. Madame Tussaud was a wax figure maker in the 18th Century, at the time of the French Revolution. So, somehow it’s a kind of diagram as well, a fake mockup of nature. That is how the first stage of photography came about. That is what they were seeking: to make a copy of reality. So even before the invention of photography, the wax figure was a representative medium. People used to believe that everything being photographed was representing reality, but now we have lost this reality because of the invention of digital cameras. I just want to fool people… There is a photograph of Catherine of Aragon the Spanish Princess, and people tend to believe it! But how can I shoot her, from the 16th Century?

To me, your pictures in the Architecture series were almost like the works by Richter. I’m curious to know what do you think about that…

Richter used photographic images to make his paintings. So he borrowed photographic images, then I borrowed the Richter images, bringing them back to photography. But they’re still paintings. So it’s going back and forth, in and out.

And what about Duchamp?

Well I think I inherited my cynicism from Duchamp – as well as from my father! They are the bad boys…

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

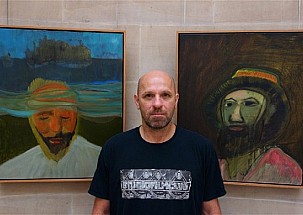

The work of Italian artist Tatiana Trouvé (1968), resident in Paris, is grounded firmly on drawing, sculpture and installations, through an inquisitive examination of concepts such as time, space and memory. Her creations and locations are like tracks left by the soul that reveal an inward-looking universe. Her work has been exhibited at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the MAMCO in Geneva, and in galleries such as Emmanuel Perrotin and Gagosian. Trouvé has won the Marcel Duchamp Prize (2007) and has twice participated in the Venice and São Paulo biennials. Her latest work is a sculpture for a public area in the city of New York. The starting point for this work is an observation I made when studying the park and its history, but also, above all, I tapped into my own experience of this place. Central Park is a natural and cultural object, a nerve centre of trends and mobility in the very heart of a city, combining a web of heterogeneous landscapes.

Tatiana Trouvé in her studio whit Lula. Photo credit: Alastair Miller.

The work of Italian artist Tatiana Trouvé (1968), resident in Paris, is grounded firmly on drawing, sculpture and installations, through an inquisitive examination of concepts such as time, space and memory. Her creations and locations are like tracks left by the soul that reveal an inward-looking universe.

Her work has been exhibited at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, the MAMCO in Geneva, and in galleries such as Emmanuel Perrotin and Gagosian. Trouvé has won the Marcel Duchamp Prize (2007) and has twice participated in the Venice and São Paulo biennials. Her latest work is a sculpture for a public area in the city of New York.

Tatiana TROUVÉ. Desire Lines 2015. Metal, epoxy paint, wood, ink, oil, rope. 350 x 760 x 950 cm. Photo credit: Emma Cole

Elena Cué: In your public commission "Desire Lines", for Central Park in New York, you created a very poetic work, envisaging a symbiosis between culture and the act of walking. The lengths of the 212 different paths around the park, like living arteries, are portrayed in huge spools of brightly coloured threads. Can you tell us about the cultural and political meaning of this work?

Tatiana Trouvé: The starting point for this work is an observation I made when studying the park and its history, but also, above all, I tapped into my own experience of this place. Central Park is a natural and cultural object, a nerve centre of trends and mobility in the very heart of a city, combining a web of heterogeneous landscapes. In this connection, it is an emblematic project of modernity. That’s why I didn’t want to create a work that was simply one more of the numerous sculptures that have been created in this context. As the artist Robert Smithson said, Central Park is, in itself, a sculpture. That’s why I decided to establish a dialogue with the park. I created a series of routes from all the roads and paths that cross the park and are open for walking. I measured these routes and then transferred their lengths to huge spools of thread, so that adding the lengths of all 212 spools on the three large frames of which "Desire Lines" is comprised gives us the total length of all the roads and routes a person can walk along.

After that, firstly, I identified each spool with the description of the route they contained and the title of a historic march, the work of an artist, a writer or a song about walking to be associated with that particular route: Selma to Montgomery March (21 March 1965), Woman Suffrage Parade (3 March 1913), projects by “walking artists” like Richard Long or Hamish Fulton, poems by Baudelaire or André Breton, essays by Guy Debord or Henry D. Thoreau, songs by Johnny Cash or Robert Johnson… In other words, a set of 212 references linking each of these paths with another path –historical, imaginary, political, cultural– and providing passers-by with a proposal that would enable them to walk again, to walk differently, around the park. And this formula sums it up: “Follow in someone else’s steps”. The act of walking has its own, singular beauty; it is an everyday, banal action, but at the same time it is a privileged manner of protest, of awakening the senses and the spirit, which is the origin of belonging to the world in a subjective way...

Drawing is the key to most of your work. This artistic discipline extends into other works such as sculpture and installations. How important is drawing for you?

It’s true that drawing occupies a fundamental place in my work. As you say, drawing is present throughout my artistic production. I draw spaces, whether in two dimensions or in three. To put it another way, my two-dimensional drawings are images of spaces and, at the same time, my three-dimensional installations build spaces that work like images.

Untitled, from the series Remanence 2008. Pencil on paper, pencil lead, tin, plastic. 82,5 x 119,5 cm

Your drawings of spatial creations are very unsettling, like “The unremembered”. The metaphorical representations of places of thought take us into a dream world, a world of the unconscious. They must be a source of self-knowledge...

I complete these two elements, space and image, present in my work, with a third: remembrance. For me, drawing means making my memory work and this is unquestionably why the terms “mental image” or “unconscious” are so often used to describe my work. However, there is something about the unconscious that interests me in particular, and that is that it is timeless. In the sphere of dreams, all times coexist and are superimposed. This is a dimension I am interested in and I effectively try to give it shape in my drawings.

Why are your spatial interventions always uninhabited?

I am very fond of a quote by the Italian architect Ugo La Pietra, who says “To live is to be at home everywhere”, meaning that to live is, first and foremost, a question of approach. I produced a work called The Guardian. Its title refers to a person assigned to a place on a chair. But this guardian only exists on the device where it is located: a copper rod is placed over the chair (guarding the guardian’s place), and the rod pierces a concrete wall from which, on either side, small bronze and plastic bags are hung. Inside this wall there are embedded works, whose “ghosts” can be seen in the material pasted on its surface. It is an absent sentinel guarding an invisible exhibition, but it is also a device that must be inhabited by contemplation, just as the images intend.

Tatiana TROUVÉ. Untitled 2014. Patinated bronze, copper, paint, concrete, leather, plastic. 180 x 454 x 250 cm. Photo crdeit: Roman März

Your work in “Bureau” is like a kind of “Remembrance of Things Past” since you created a work of art from all the time you had to waste looking for work or doing daily chores that took you away from your artistic activity. How important is the concept of time in your work?

I don’t think of time in its abstract dimensions, on a scale, for example, of cosmic time and its infinite duration. I have seen time as a material of my work since I created Bureau d’Activités Implicites (Office of Implicit Activities), the first module of which I made in 1997. It’s time on a human scale, a time we experience. Hence, its not so much a concept as a reality we experience in its various manifestations: time for waiting, time for searching, time for wandering. But what interests me even more is the coexistence of times. I see time as dual. The present is dual, it has two coexisting facets: the present is the past passing. I have made a series of works called I Tempi Doppi [Double Time]. Each of the works in this series comprises a lit light bulb linked by a copper wire to an unlit light bulb. The past and present feed each other, maintaining a singular relationship whereby one seeks to switch off the other, because the past is also made of present that passes. Time is dual, because it works in a dual way.

What is the most important thing art has given you?

Art has given me what I have taken from it.

“Double Bind” is the name of your first major exhibition in Paris’s Palais de Tokyo, whose title alludes to the irresolvable situation that emerges when we are faced with an intrinsically paradoxical message. What is your interest in opposites and the tension they emanate?

This title, Double Bind, responded to the spatial proposal I had devised for this exhibition at Palais de Tokyo. The tension was in the space itself –there was no psychological component, unlike the standard usage of that expression. And it was not embodied by a contradiction, but by an echoing structure that perturbs our potential understanding of it, causing a feeling of floating between one and the other. Incidentally, what interests me is not the tension itself, but what it opens up: this interstitial space-time or these inter-worlds and the floating attention they generate when we install ourselves in them.

Your work is full of meanings, and there is an interesting underlying discourse. Is the spectator’s immediate aesthetic experience of your work enough, or do you think some prior knowledge is required?

We must trust those who are looking, because aesthetic experience is on their side. There are many ways to activate the potential of the works, but first and foremost you need to be constantly involved. Involvement: “perception requires involvement” is the title of a work by Antoni Muntadas, who asserts that the senses must be emphasised in order to understand a work, but also that anyone can do it using their own means. But, without that commitment, aesthetic experience is not possible. It all begins with this increase in involvement, and this is also what can lead you to research a process or a particular work. Of course, the works offer different approaches to this experience. If I take the example of Desire Lines, a small explanatory text is outlined at the start of the reproduction of the lengths of the paths in the park represented in the spools of thread. Afterwards, it is up to each person to carry on. The simplest way is by reading the titles of the spools and evoking the walks they recall, to which one may add one’s own memories, considering the various complete references of the titles given to the various routes, which make the historical, cultural and political references appear more explicitly, allowing one to submerge oneself in the history of the march. But it is also possible to take a walk around the park, interpreting the present cultural and historical elements, either by reading a poem or a book, listening to a piece of music, or through the documentation on a historical march or artist’s representation.

By activating each of these modes of operation, the person looking/walking will be following in the footsteps of another. To varying degrees, they will place the work in motion. Various readings are always possible, and none is imposed, but the ones that work are all based on an approach proposed by the work itself.

Through your art, are you asking questions or providing answers?

Personally, I don’t think art either asks questions or provides answers. I think art bewilders; in other words, it invites us to think differently, by shifting around our references.

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

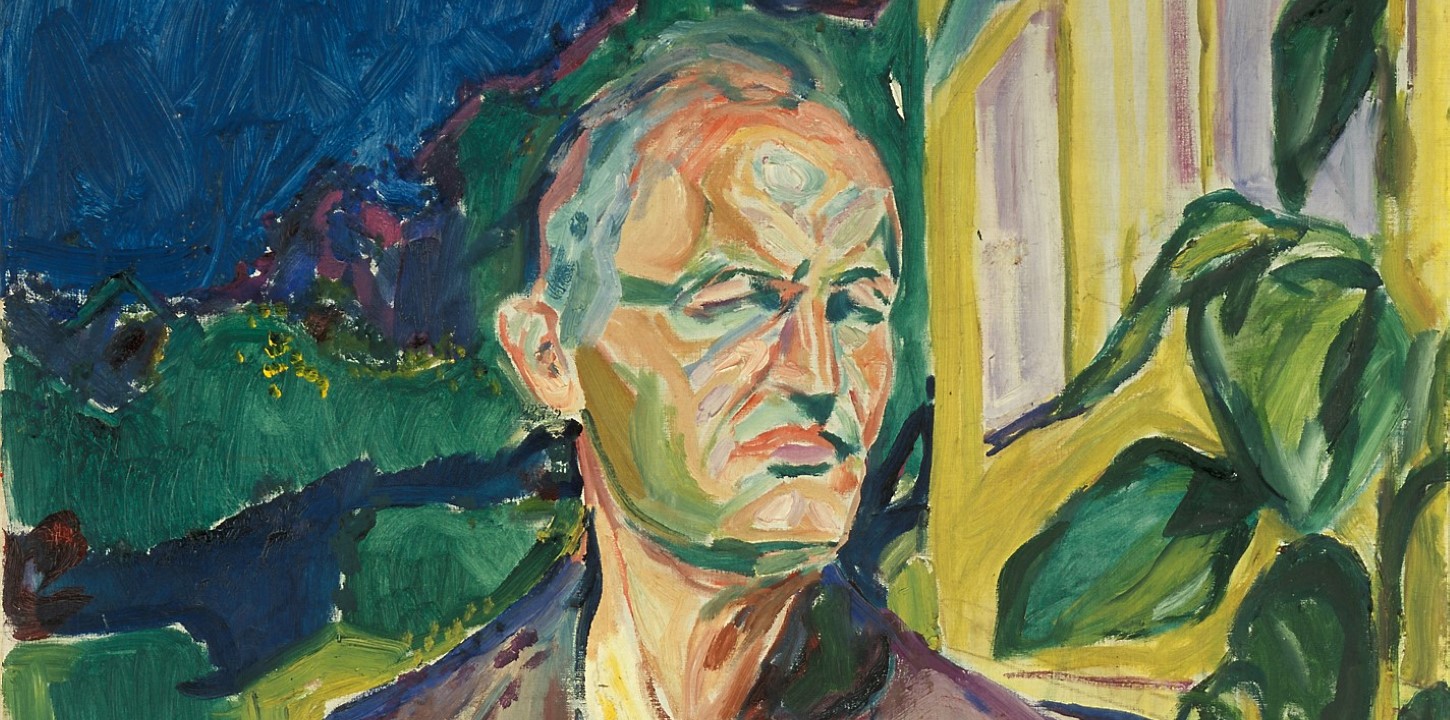

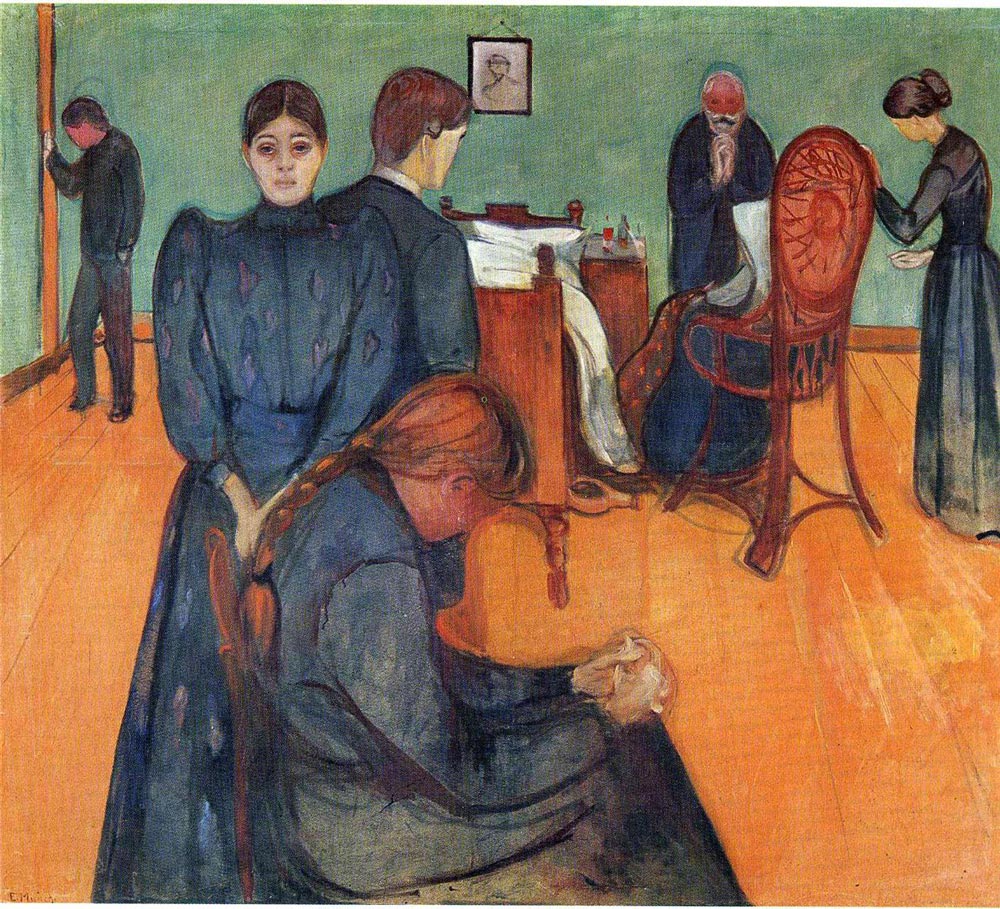

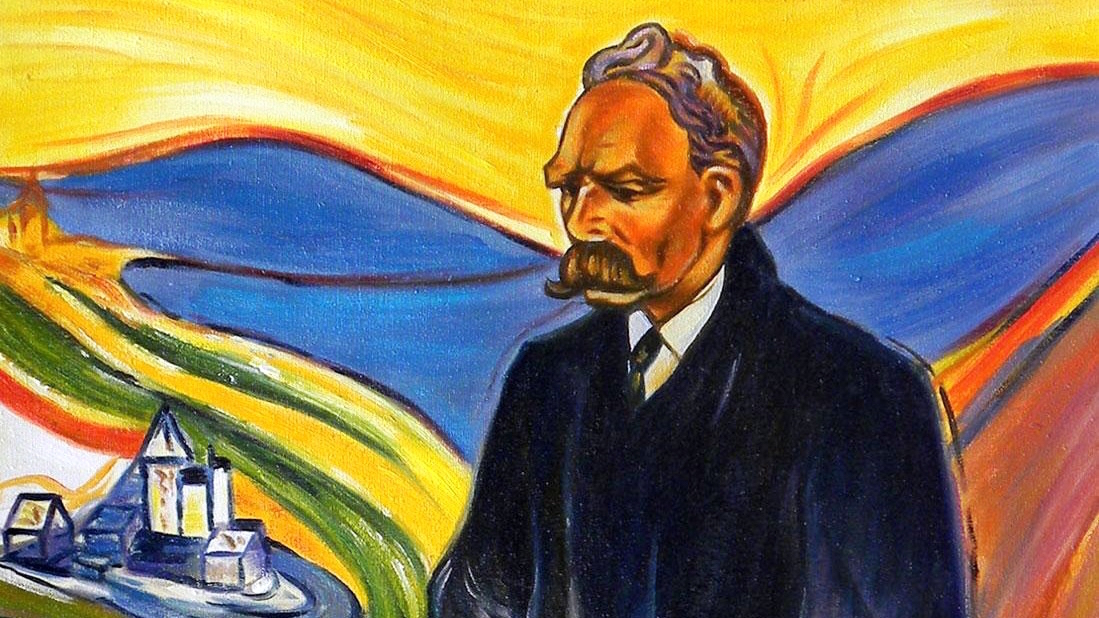

The galleries of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum have recently opened an exhibition by artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944), successfully curated by Paloma Alarcó, that enables us to “listen to the dead with our eyes”. Paintings and writings come together in the museum’s galleries, divided into emotional Archetypes to communicate this artist’s obsessions from throughout his intense life. People think that you can have a few friends, forgetting that the best, most authentic and above all, most numerous, are the dead. I intend to engage in a series of conversations with the afterlife. As the tormented spirit of the Norwegian artist has circumstantially settled in Madrid, I enthusiastically headed there to learn more. I always felt like I was treated unfairly during my childhood. I inherited two of the worst enemies of mankind: tuberculosis and mental illness. Disease, insanity and death were black angels beside my crib.

The galleries of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum have recently opened an exhibition by artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944), successfully curated by Paloma Alarcó, that enables us to “listen to the dead with our eyes”. Paintings and writings come together in the museum’s galleries, divided into emotional Archetypes to communicate this artist’s obsessions from throughout his intense life.

People think that you can have a few friends, forgetting that the best, most authentic and above all, most numerous, are the dead. I intend to engage in a series of conversations with the afterlife. As the tormented spirit of the Norwegian artist has circumstantially settled in Madrid, I enthusiastically headed there to learn more.

Let’s start with your childhood.

I always felt like I was treated unfairly during my childhood. I inherited two of the worst enemies of mankind: tuberculosis and mental illness. Disease, insanity and death were black angels beside my crib. A mother who died early, planting me with the seed of tuberculosis. A hyper-nervous, pietistic father, religious to the point of being crazy, from an ancient lineage, planting me with the seeds of insanity.

When you think about those years, how did you feel?

The angels of fear, pain and death were beside me right from birth, going out to play with me, following me under the spring sun, in the splendor of summer. They were with me at night when I closed my eyes, threatening me with death, hell and eternal punishment. And I often woke at night and looked around the room with panicked eyes thinking “Am I in hell?”.

The fear of death tormented me, and this fear harassed me through all of my youth.

Heaven and hell, how do you envisage eternity?

Flowers will emerge from my rotting body, and I will be part of them. That is eternity.

And where is God?

With fanatic faith in any religion, such as Christianity, came atheism, came fanatic faith in the existence of no God. And with this non-faith in God there was content, becoming a faith itself in the end. It is generally foolish to assert anything about what comes after death.

But what is it that gives strength to the Christian faith. There are many who have difficulty in believing it. Although one cannot believe that God is a man with a big beard, that Christ is the Son of God who became a man, or in the Holy Spirit formed by a dove, there is much truth in this idea. A God as the power that must be at the origin of all, a God that governs everything. We can say that he directs the light waves, the movement of the tides, the center of energy itself. The Son, the part of this energy that is in man, the immense energy that filled Christ. Divine energy, genius energy and the Holy Spirit. The most sublime thoughts sent by the sources of divine energy to the human radio stations. In the very depths of beings. That which is provided to every human being.

But what do you think death is?

Dying is as if the eyes have been switched off and cannot see anything else. Perhaps it’s like being locked in a basement. You are abandoned by all, they closed the door and left. You see nothing and only notice the humid smell of putrefaction.

And what about life?

I have been given a unique role to play on this earth that has given me a life of illness and also my profession as an artist. It is a life that does not contain anything resembling happiness, or even the desire for happiness.

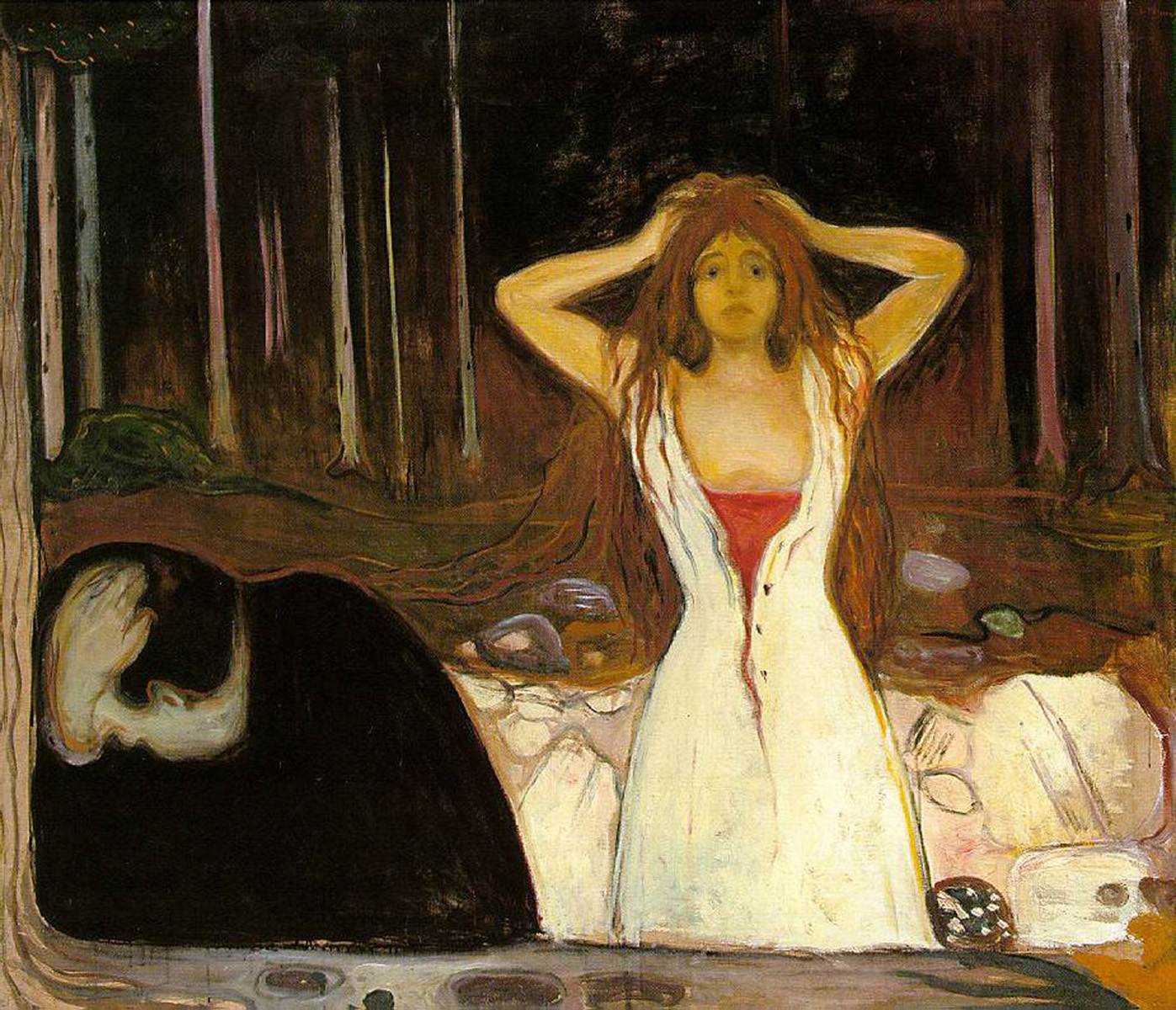

Not even love?

Human destinies are like planets. Like a star that appears in the dark and meets another star, glistening in a moment, to then return, fading into obscurity. So as well, a man and a woman meet, they slide towards each other, shining in love, blazing, and then disappear, each one for himself. Only a few end up in a great blaze in which both can fully join.

The ancient were right when they said that love was a flame, as the flame leaves behind only a pile of ashes. Love can turn to hate, compassion to cruelty.

Jealously is closely linked with love, how would you describe it?

Jealous people have a mysterious look, many reflections focus in those two sharp eyes, like in a crystal. The look is exploratory, interested, full of love and hate, an essence of what we all have in common.

Jealousy says to its rival: go away, defective; you’re going to heat up in the fire that I have lit; you’ll breathe my breath in your mouth; you’ll soak up my blood and you will be my servant because my spirit will govern you through this woman who has become your heart.

Now let’s talk about art… where does it come from?

Art generally comes from the need of one human being to communicate with another. I do not believe that art has not been inflicted by the need for a person to open his heart. All art, literature as well as music, has to be generated with the deepest feelings. The deepest feelings are art.

What is the purpose of your art?

I have tried to explain life and the meaning of life through my art. I have also tried to help others clarify life. Art is the heart of blood.

We must no longer paint people reading or women knitting. In the future we must paint people who breathe, feel, suffer or love. As Leonardo da Vinci dissected corpses and studied the internal organs of the human body, I try to dissect the soul.

Conclusion.

My art is based on one single thought: why am I not like the others?

How do you think the audience should approach art?

The audience must become aware that the painting is sacred, so that it unfolds before them like in church.

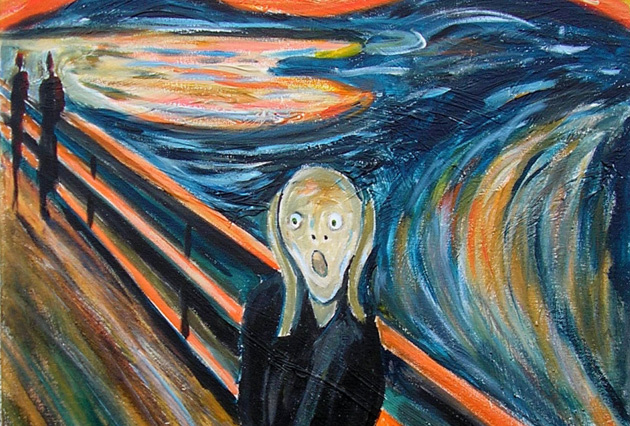

One of your iconic paintings is The Scream, could you explain the origin of such a radical emotional expression?

I was walking along the road with two friends, the sun was setting. Suddenly the sky turned a bloody red. I stood, leaned on the fence feeling deathly tired. Over the blue-black fjord and city hung blood and tongues of fire. My friends walked on and I remained behind, shivering with anxiety. And I felt the immense infinite Scream in Nature.

Your love of photography is known, what do you think of photography as another mode of artistic expression?

The camera cannot compete with the brush and palette as long as it cannot be used in heaven and hell.

Where is the beauty in your art?

The emphasis on harmony and beauty in art is a waiver to be honest. It would be false to only look on the bright side of life.

Your writing has a strong aphoristic style. We’ll finish there…

Thought kills emotion and reinforces sensitivity. Wine kills sensitivity and reinforces emotion.

- A conversation with Esvard Munch- - Página principal: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

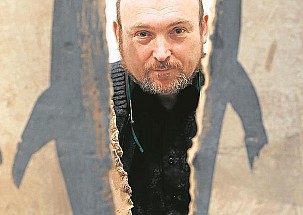

Martín Chirino (Las Palmas, 1925) grew up on the beach of Las Canteras, feeling the sand, the sea and the breeze whilst watching a horizon that he dreamed of moving. The earthiness, ancestry and mythology of his birth place purify the forger’s soul through fire to take a new form in material, in this case iron, arisen from the deepest interior of this wind sculptor. This particular place has rooted him to primeval and his dreams and desires have lead him to that which is universal. The spiral, the symbol of origin and formation of the universe, defines this artist in constant search of the truth. “Look at this sculpture, I’m going to make it a tribute to Picasso. Look at the beauty that’s going to remain underneath, the beauty of the shadows. It’s easy to draw or paint shadows, but the challenge for a sculptor is to materialize them, to give them body weight.”

Martín Chirino (Las Palmas, 1925) grew up on the beach of Las Canteras, feeling the sand, the sea and the breeze whilst watching a horizon that he dreamed of moving. The earthiness, ancestry and mythology of his birth place purify the forger’s soul through fire to take a new form in material, in this case iron, arisen from the deepest interior of this wind sculptor. This particular place has rooted him to primeval and his dreams and desires have lead him to that which is universal. The spiral, the symbol of origin and formation of the universe, defines this artist in constant search of the truth.

“Look at this sculpture, I’m going to make it a tribute to Picasso. Look at the beauty that’s going to remain underneath, the beauty of the shadows. It’s easy to draw or paint shadows, but the challenge for a sculptor is to materialize them, to give them body weight.”

Why don’t you tell me about the shadows of your life?

I believe that we all have an inner character that gives us answers and questions us, a character that you converse with. I am a calm person because I look for the answers within and my surroundings have little impact on me. I realized at a very young age upon reading Demian by Herman Hesse, which struck me in both senses, that the protagonist was always talking to himself and was able to bring out a truth drawn from reality...

And when did you discover your other side?

I am number 12 of my family. I was a kid living in a very big house, on the beach of Las Canteras and from a young age I was in search of my own space, my refuge, in a lost bedroom, so things happened in there. And I think that that’s where my other personality was shaped. I used to sit with my legs either side of one of the doors in the room where we kept the sheets and I always used to hide there.

And with so many siblings, how was your relationship with your mother?

Very good because my mother was an only child, she married my father and started having children. She used to read Balzac and she loved his work because he describes very interesting things and things that reflected life itself. She had no literary judgment but a passion for reading everything. And she read it to the people who she worked in the house with. My mother was a very special person and I always got along with her really well. She was very calm, very soft, but she also had inner strength.

And what do you long for?

I think I’m missing a place where I can belong and just be. My whole life and artistic career has been conditioned by this search.

Throughout your life, what discourse do you think your work has had?

My inspiration has never been divinity, my inspiration is life itself. I’m talking about a spiral that is identity, because it is the spiral of my land and it makes me feel Canary. One day I asked myself why and, in the end, I realized that my fable ability is the same as anyone’s else but what I’ve really done is look and look in a comprehensive manner. I began to study the whole course of the spiral, not only in my town but in others, and how soon you realize that you haven’t discovered everything that you were searching for in any of them. The most that can be said is that the spiral is a cultural symbol, although no one knows why it is present in the whole of the universe.

From the Canaries you settled in Madrid, where you lived for several years, and then left for New York…

From Madrid I ended up leaving for New York, but before that, there was a final touch there: the poet John Ashbery, who had come to Franco’s Spain together with Frank Ohára. I was the translator for both of them because there were not many people who spoke English in Spain at the time. They came for a few days and had to mount an exhibition at the MoMa and as I translated for them, Juana Mordo was always getting angry with me because she thought I hadn’t said what she wanted.

You were an avid reader, what writers have really influenced you?

Many writers, but Joyce was a passion of mine, I also read it in English. I even went to Ireland, to Dublin, after reading Dubliners, to see if I could learn something from that. I didn’t find anything. I asked myself, where were the Dubliners from Dubliners? But in the most exquisite sense, I didn’t get to meet Joyce’s Dubliners. It was too late, it was not the right time in history.

You said he was the cause of your insanity...

Until I gained a little understanding of Finnegans Wake, an impossible work that I then managed to translate into my vision of a Latino man. That’s why it’s very beautiful in Ulysses, when Joyce puts himself in such a strange position, as if he was God. It was set out to achieve a whole, complete thought, it was very difficult, and he didn’t achieve it… no one achieved it.

But we try…

Perhaps our unhappiness lies here.

And apart from Joyce, what writers have affected you?

Ortega y Gasset: he taught me to find a way of expression. It was extraordinary for me and I don’t think that anyone has handled Castilian better, in such a coherent, perfect way as Ortega y Gasset. I had a passion for it, I even carried El Espectador with me as if it were a comic. Then there’s poets, like Antonio Machado, whose thoughts and metaphors I constantly follow.

And do you write?

I’ve never wanted to be a writer because it scares me, because the written word has problems, because you express thought. Rigor will not let me. I write for myself, things about me, what I know, what I feel, what I think. It’s as if I had written myself.

And what about that phrase of yours, that you don’t make a sculpture but you write a sculpture?

I mean that at the time of making them I have to develop a coherent discourse so that it’s understood, it’s as if it’s written. I write about the circumstances on pieces of paper, a beautiful phrase, what I make of it. I interrelate it all to see what’s going on, it’s a way of understanding it.

Are your values unstable as a result of living in such turbulent times as you have?

You are not born with values, but you acquire or improve them over time, enriching yourself. Obviously I, like everyone else, have had great trouble for blindly believing something that was not proven. What the church says is somehow passable, conversable, and everything that is conversable is subject to the possibility of this change. But you have to be aware and then step forward and put yourself in another situation. My mother taught me the most basic values, she taught me to be religious and I do not want to fail her so I’d rather believe than not believe, it is a choice, I do it out of respect for my mother. Because if I want to reverence things, I want to respect…

But do you really feel the faith? Or have you managed to keep it up based on desire…

No, because I think that thought is not only subject to passion, but also the brain. I mean, I said the word “reverence”, reverence is something self-imposed. But no, I have the chance to demand things of myself, like anyone else.

So we’re not talking about faith, but a rational insistence and desire…

Using my brain to keep faith in some values, out of love for my mother.

To keep it, you must practice it… do you consciously practice it?

Of course, I have great respect for others and my mother is the person who I respect most in the world because she taught me things that created great happiness when I was little. And when I grew up she continued being my friend, someone who loved me, and she said to me: you have to really respect others so that they respect you.

Apart from your mother, what other people have affected you most during your life?

One is more frivolous and the other may be more fictitious because he belongs more to the world of art. One is Donatello, someone who impresses me, who has always drove me crazy and his work leaves me shocked when I see it. The other is Greta Garbo, a symbol for me, a cold, untouchable image, I liked her so much…

And what has remained true after so long?

I think the only thing that has really mattered throughout my life is being a liberal, and therefore being liberal and understanding even what destroys me. It’s good, it’s better.

- Interview with Martin Chirino- - Página principal: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Berlin. On a sunny day, strong rays illuminate the studio where Thomas Struth (Geldern-Germany, 1954) meets with me to begin our conversation. This artist with an intense and precise gaze is one of the most interesting photographers of our time and belongs to the prestigious Dusseldorf Academy.

It appeared, I think, when I was almost 13 or so. Because it was not really a calling to want to be an artist, but I started to like drawing and using water colours and oil-chalk, and I painted my first oil paintings when I was 14. I had a room at my parents’ house, maybe 8 square metres or so, really a very small room. But I just liked to do that and I always loved music.

I started to learn the clarinet, then, when I was 14 my music teacher told me I should switch to saxophone and he started a school jazz band. So I played in the school jazz band for three or four years and then there was a time of pop music. Anyway I didn’t think about whether I wanted to be an artist or not, because that just wasn't the question. I didn't see myself becoming an artist, which I think was good because I didn't bother thinking about the future, I just did what I wanted to do at the time.

It’s important to note that you were the first artist to receive a grant to be in residence at the PS.1 Studios in Queens, where they dedicated an exhibition to you. Was this your first one?

Later on, you were a Professor of Photography at the University of Art and Design in Karlsruhe from 1993 to 1996, after already establishing yourself as a well-known artist. What was this teaching experience like?

I think I learned a lot about photography. He had developed an idea with new patients who came to look for help, where they'd tell a story and create a narrative about what they believed they suffered from and what they thought the cause might be. He asked them to bring 3 or 4 photographs to show what their family life was like. When we met and got to know each other, he found out that I was a photographer with a darkroom and the tools to print. So he told me that it was a dream of his for a long time to collect pictures like this and bring them together and work with them and make an exhibition at the institute where he was working. I said yes, I was interested, so we collected these photographs from about 35 people. Everyone brought about 2 or 3 photographs, so we had 80-100 pictures and I reproduced them all, made them all the same size and all in black and white, because before they were all in colour and I wanted to make them more comparable.

In the beginning, it was black and white because I couldn't afford to pay for the materials myself. I didn't have a colour printer. I didn't have the money for colour film, or the development. But the contact sheets and black and white were fairly inexpensive, so that had a very simple reason. Later I started to work in colour, but you don't look properly when you look at scenery in colour. When you photograph in black and white, you look at things in a different manner because you think more of cubic volume and light and shadow and stuff like that. You have to ignore the colours; you judge everything only by the density of light. Whereas with colour, of course you only look at the colour. You look at one scene and there's a bright red and then there's a bright yellow. You would find the attractive point in the picture where there's a dominant colour. When you have a blue sky and you photograph in black and white, the blue sky doesn't matter. If you have it in colour, the blue is dominant and it's an intense element in the photograph. Because when you look at it, the sky, it's air. But in the photograph it's a blue colour. It's blue paper. So it's a different thing. That's why, when I want to make a print now with the blue sky, my aim in the printing process is to make sure it looks like air. And not like blue paint. It's a very fine line.

Your photographs of urban landscapes in Unconscious Places seem rather objectified. Do they have any association with “Non-Places” by French Sociologist and Anthropologist, Marc Augé?

No that was not what I wanted to do. Everything is created by man. What I wanted to say with the title Unconscious Places is that when people design a building like this one or the curved one, the architect and the people who pay for it - or give the permission for it - believe it has to be contemporary. But beyond all this, it unconsciously creates an atmosphere that radiates to the people. I mean, the people who live over there in those buildings will look out at that building all the time when they look out of the windows. And the building is much uglier on that side there! So it's something that has a strong unconscious element, which matters a lot for the atmosphere for the city and the people who live in that building. Because the architect doesn't live in that building… They live somewhere else. Maybe in an old farmhouse, I don’t know, maybe in a pre-war building that is nicer. And maybe it has something to do with anger. So all cities are filled with this underlying unconscious, atmospheric energy. That was something I wanted to highlight.

The themes in your work could be like a socio-political analysis, because they reflect our current reality; family, technological and social structures...

I love to make pictures. I have to have a reason to make a picture. It's more fun to give myself a challenge in making a picture than to make pictures of the most obvious things. But I have to find excuses. There are all these questions about responsibility and society and questions about existence and the different levels of influences that exist. Picture making has a lot to do with that, to find reasons to make my pictures. But in principle, I have a strong urge to speak through pictures and not through talking.

Yes, you know some people speak through music, or architecture or sculpture or pottery… It’s a strategy to form an identity with the work you're doing. On the other hand, it's a problem to over-identify yourself with what you do. I think I'm a very invested artist, but sometimes I feel that I don't identify completely with the art world.

I think the conscious absence of people is necessary to show that what you're looking at is a human creation. And so the mentality and everything that humans represent is expressed through the buildings. With too many people it would just be a normal street scene, with people in houses and you wouldn't get that feeling.

During our discussion of how inspiration arises, I remembered your Paradise photographs, some of which were taken in Australia. Were you searching for inspiration there or did it come naturally?

I used to have an apartment in Düsseldorf for a long time with a terrace towards the back garden. I often used to have breakfast there, read the paper and observe the visual structure of the trees and branches, the information flow of these patterns. That stimulated the idea to make these kinds of pictures that would be very crowded with information which would make you surrender to the act of observation rather than interpretation. However, it could not be a German forest with pine trees and their dominating verticality. It needed to be something wilder, so I thought that jungle, primeaval forests would be good. I had a few trips scheduled, to Australia because I was invited to the Sydney biennale in 1998. In the North East of Australia, there's a jungle area that used to be connected with Indonesia. These two continents separated, so there's this jungle area north of Daintree. It's quite amazingand I came back with five pictures.

In any case, these days we're so used to taking so many photographs digitally.

Yes but I use a much bigger camera , so it is very complicated and it takes a lot of effort.

What is your concept of paradise?

Paradise is a condition of mind, soul, emotional quality I would think. I decided on this title to make sure people don’t think the work describes botanical differences etc.

It has different elements. You are confronted with yourself to a stronger degree. The constantly moving growth around you is very elemental. Nothing stays the same at all times, everything moves very slowly. As a friend of mine said, as soon as you stand still for a while insects and other animals appear, believing that you're something they could eat. So you're easily confronted with your anxieties. In that respect, there are confrontational elements. But the pictures are pictures, so what I think the pictures do is make the observer very calm. Because you can see it’s a jungle, so you don’t have to identify an assembly of objects: a carpet, a chair, a table, a woman, child, etc.. We cannot stop naming what we see. But when you look at the jungle photograph you don’t have to. You can refrain from this impulse.

You were the first photographer to exhibit at the Prado Museum. Could you tell me how you feel about that experience?

In my museum work, I wanted to connect with the paintings I chose in a particular way, through photographing groups of visitors corresponding with the figures in the paintings I photographed. It was maybe like an attempt of resurrection, to give people a hint that these master works or so-called master artworks were not created as such when they were made. They were made by artists in particular circumstances of their daily life and these works were not born as the famous artworks that they are now. I wanted to make them look like more contemporary works. The interesting question is: why do works of art speak to us? Why do we even want to look at them? Because they were made with condensed information about love and desire and beauty and all kinds of complex emotional qualities? Because of their artistic craftsmanship? What resonates in us during the observation, which is a playful process, and one thing that destroys play is too much respect. When you have too much respect you cannot play, you are intimidated, you become passive. I felt that people would go to museums with too much respect. They don't really know what they’re allowed to think. Maybe in the end they only go to those museum galleries because they know the artists or the specific paintings are famous. The peak of the phenomenon is the Mona Lisa and the way it's presented now at the Louvre, which is quite a carricature. I think what happened was that the artworks in my photographs became a little bit more contemporary and the visitors were pushed back into history, because once I've photographed them, the moment has of course already passed. It created this double reflection of consciousness.

I thought to do that would be amazing, so I decided to fly to Madrid and meet Miguel Zugaza. Then at the time, I had a fever and was not very well and I thought it was a bad sign, but anyway I went to the meeting and I was coughing all the time but we liked each other immediately. And then he said "I want to support you to do that". And that’s how it began… When I was about to start, he talked about inviting me to help open the new building and I thought that would be quite amazing. I showed these three friezes - one of the Hermitage in St Petersburg, one of the Accademia in Florence and one of the Prado. And then I thought I would have to convince the board, so I hired a video projector and made a PowerPoint presentation in the construction site. Then they started to talk about offering to show some of my works amongst the paintings, which I found extremely strange and I was not so sure if I could handle that or if that would be a bit too much. Because I think photography and painting don't go together so well. Photography and sculpture go well together but photography and painting don't.

Well, I do use minimally invasive digital corrections, but I’m not inventing anything. The digital process allows me to deal with partial contrast and colour changes or adjustments in a much more finely tuned way than in the darkroom. The more recent pictures are mainly photographs taken with large format and sheet film, scanned into a file and then we work from the file.

Can you reveal anything about your new project in Israel for the Marian Goodman Gallery in London?