On a scale of difficult to … how does one even begin to guess what was going through Leonardo da Vinci's mind on seeing a woodpecker for the first time? "Describe its tongue," the painter asks himself in one of the many little notes scribbled in the margins of a notebook ... "The tongue of a woodpecker can extend more than three times the length of its bill. When not in use, it retracts into the skull and its cartilage-like structure continues past the jaw to wrap around the bird’s head and then curve down to its nostril." In the concluding pages of his book, Walter Isaacson (New Orleans, 1952) establishes an imaginary dialogue between his reader, Leonardo and himself in which he offers us a clue: "There is no reason you actually need to know any of this. But I thought maybe that you would want to know. Just out of curiosity. Pure curiosity.”

|

Author: Marina Valcárcel

Art Historian

|

|

Lady with an Ermine (1490), National Museum of Krakow

On a scale of difficult to … how does one even begin to guess what was going through Leonardo da Vinci's mind on seeing a woodpecker for the first time? "Describe its tongue," the painter asks himself in one of the many little notes scribbled in the margins of a notebook ... "The tongue of a woodpecker can extend more than three times the length of its bill. When not in use, it retracts into the skull and its cartilage-like structure continues past the jaw to wrap around the bird’s head and then curve down to its nostril." In the concluding pages of his book, Walter Isaacson (New Orleans, 1952) establishes an imaginary dialogue between his reader, Leonardo and himself in which he offers us a clue: "There is no reason you actually need to know any of this. But I thought maybe that you would want to know. Just out of curiosity. Pure curiosity.”

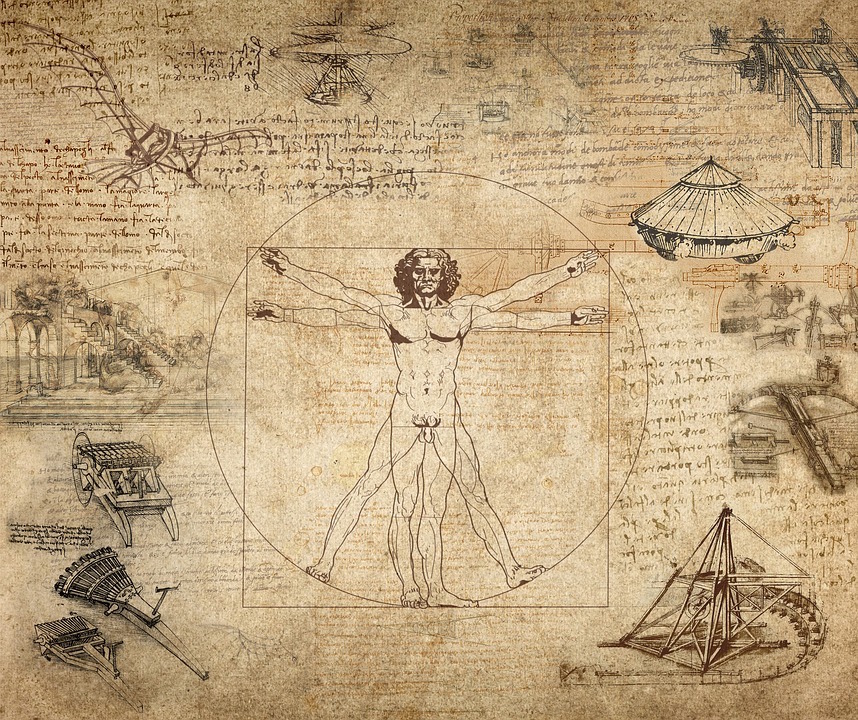

This is at the end of the book and also at its heart. The word "curiosity", repeated throughout its 624 pages, is one of the axes on which the description of the genius that was Leonardo (1452-1519) revolves and why the author acknowledges that this biography is based not on his paintings but on his notebooks. He believes the 7,200 pages of miraculously preserved notes, drawings and sketches are what hold the key to the enigma of "the most curious man in history", as Kenneth Clark dubbed him.

Vitrubian Man (1490), Accademia Gallery, Venice

Leonardo's fascination with the world and his observations of it were what predominated his thoughts and unbounded imagination. The notebooks are the record of a stubborn, daring, unstoppable mind. The author wants to breathe all of this into us, as if, through a kind of mental gymnastics, we readers could also grasp some of Leonardo's brain. The genius of one of history’s greatest visionaries was born of abilities that we ourselves possess and are also able to stimulate. His curiosity, like Einstein's, was mostly concerned with phenomena that wouldn’t even occur to most people over the age of ten: How do clouds form? Why do our eyes only see in a straight line? What makes us yawn?

Isaacson, a former Time Magazine editor, is obsessed with talent. The New Yorker writes that this book is a study on creativity, how to define it, how to achieve it. And this is what led its author to choose the figure of Leonardo to follow on from his previous biographies of Einstein, Kissinger and Benjamin Franklin, all of whom established connections between different disciplines: they knew how to link observation and creation. In his penultimate biography, Isaacson quotes Steve Jobs, for whom Leonardo was a hero: "He saw the beauty in both art and engineering and his ability to combine them made him a genius.”

Foetus in the womb, inspired by the dissection of a pregnant cow (circa 1511), Royal Collection, Buckingham Palace

The desire to know

This book portrays, essentially, a man consumed by the desire to know. A son born out of wedlock, vegetarian, homosexual, fashion buff with a penchant for dressing in pink and linen, his love of animals preventing him from wearing anything dead on his person. But did he ever live with his mother? Who did he love and, above all, who loved him? There are chapters dedicated to his childhood and his death in the arms of Francis I in Amboise.

It would seem that 1452 was a fine time for a child with such skills to be born: Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press. The Ottoman Turks were about to invade Constantinople, which led to mass exile to Italy by scholars laden with manuscripts containing the ancient wisdom of Euclid, Plato, Aristotle ... And just a year separated the births of Christopher Columbus, Americo Vespucio and Leonardo.

La Belle Ferronière (1480-1495), The Louvre, Paris

Leonardo had almost no formal schooling: self-taught, from a young age he would tie a notebook full of enigmatic and invariably undated writing to his belt. He wrote from right to left, thus producing his specular calligraphy - "It should be read with a mirror," Vasari wrote - using his left hand to move backwards without smearing the ink. The pages are full of wild leaps, from the description of a mechanical problem to the curl of a lock of hair. However, it was there in those pages that he wound up weaving the key to his art: the interconnection between Nature, the human being and the Earth. He accompanied his drawings with texts whose shapes can be found similarly in branching trees, the arteries of the human body and in rivers and their tributaries ... whilst at the same time, in some page corner, he jotted down the formula for hair dye. This tower of Babel, this medley of multicoloured splashes of ink, leads us to marvel at a universal mind which scoured the arts and sciences with abandon and awe and in so doing perceived the connections that occur in the universe.

The Virgin of the Rocks (detail) (1483-86), The Louvre, Paris

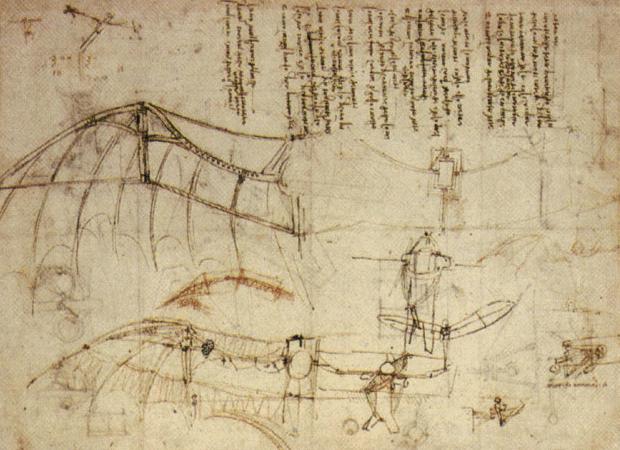

Birds, waves

And so Leonardo set to observing birds, researching how they flew and even the possibility of designing machines that would allow humans to fly. He painted the elegance of the birds as they turned, soared and manoeuvered in the wind. He pioneered the use of arrows. No scientist before him had shown how birds were able to remain aloft. And he corrected Aristotle: "In order to give the true science of the motion of birds within the air, it is necessary first to give the science of the winds, which we shall prove by means of the motions of water within itself." Not only did he understand fluid flow patterns and their dynamics but his ideas predated those of Newton and Galileo. He also observed the flight of a partridge: "When a bird with a wide wingspan and short tail wants to take off, it will lift its wings with force and turn them to receive the wind beneath them."

Articulated wings, emulating those of birds

In the meantime, he was also studying the Earth as a planet. In 1508 he summed it all up in his notebook, the Leicester Codex. In it he wondered: Why do springs originate in the mountains? Why do valleys exist? What makes the moon shine? How did fossils make their way up mountains? What makes water and air whirl? And the most surprising, why is the sky blue?

The current owner of the Leicester Codex is Bill Gates so, although Isaacson makes no reference to it, some of its digitalized pages are used as screensavers by Microsoft.

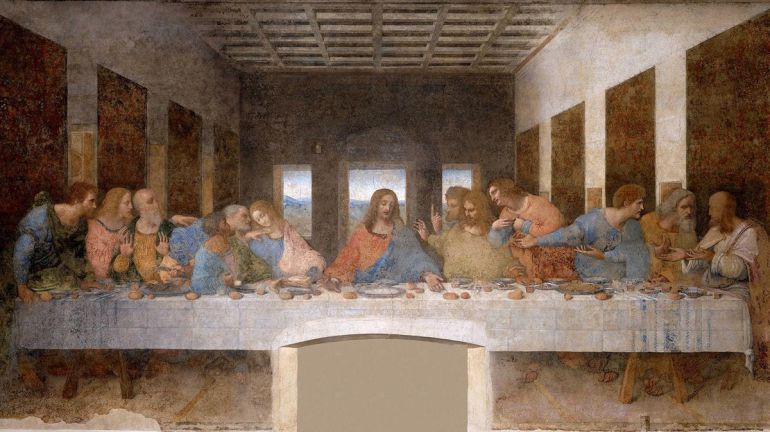

His studies on the movement of water also led him to understand that of waves. He noticed that they don't necessarily push water forward. Sea waves and those caused by a stone falling into a pond advance in a certain direction but all these what he called "tremors" do is cause a momentary swell before returning to their starting point. He compared them to the undulations caused by the wind in a cornfield. He even believed that emotions could also spread in waves. One element of the narrative of the Last Supper is the waves of emotion that Jesus causes after saying, "Truly I say unto you that one of you will betray me."

The Last Supper (1495-97), Refectory of Santa María della Grazie, Milan

Also blended seamlessly through Isaacson's pages are paragraphs on many of Leonardo's works of art, his discoveries, his techniques and the description of his paintings from Salvator Mundi and the Virgin of the Rocks to the Man of Vitrubio and The Last Supper. In Ginevra De'Benci's portrait, Leonardo portrays a melancholy young woman against a background of juniper bushes (Ginevra meaning juniper in Italian). Leonardo applied not old-fashioned tempera but hundreds of layers of oil paint so as to make Ginevra's curls and the button at her neck appear to be forged from light. And let’s not forget the similarity of the colours of her dress to the landscape in the river water and the shadows cast by trees. "Ginevra has remained at one with the land and the river that binds them."

Ginevra de' Benci (1474-76), National Gallery of Art, Washington

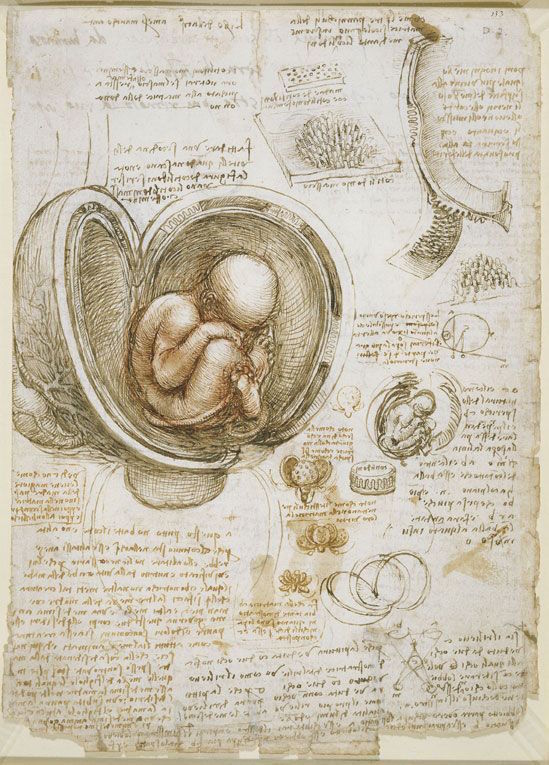

Human anatomy

In 1508, in a Florentine hospital, he would strike up a conversation with a hundred-year-old man who was to die a few hours later. Leonardo dissected his body. On one of his notebook pages, above several sketches of the muscles and veins of a partially skinned corpse, he made a note of the centenarian’s face. Then, over the next 30 pages, he proceeded to make notes of what he saw. His rudimentary instruments for dissection enabled him to discover, layer by layer, the body while the body, being untreated, decomposed. First he showed the elderly man’s superficial muscles, then he removed the skin and showed the inner muscles and veins. Of all the related muscles and nerves, the ones controlling the face seemed to him the most worthy of study. He drew a cross-section of the spinal cord and all the nerves leading from the brain. He ascertained from the corpse that it is the cheek muscles that move the lips. They were the first known examples of the scientific anatomy of the human smile. At the time, Leonardo was working on the Mona Lisa.

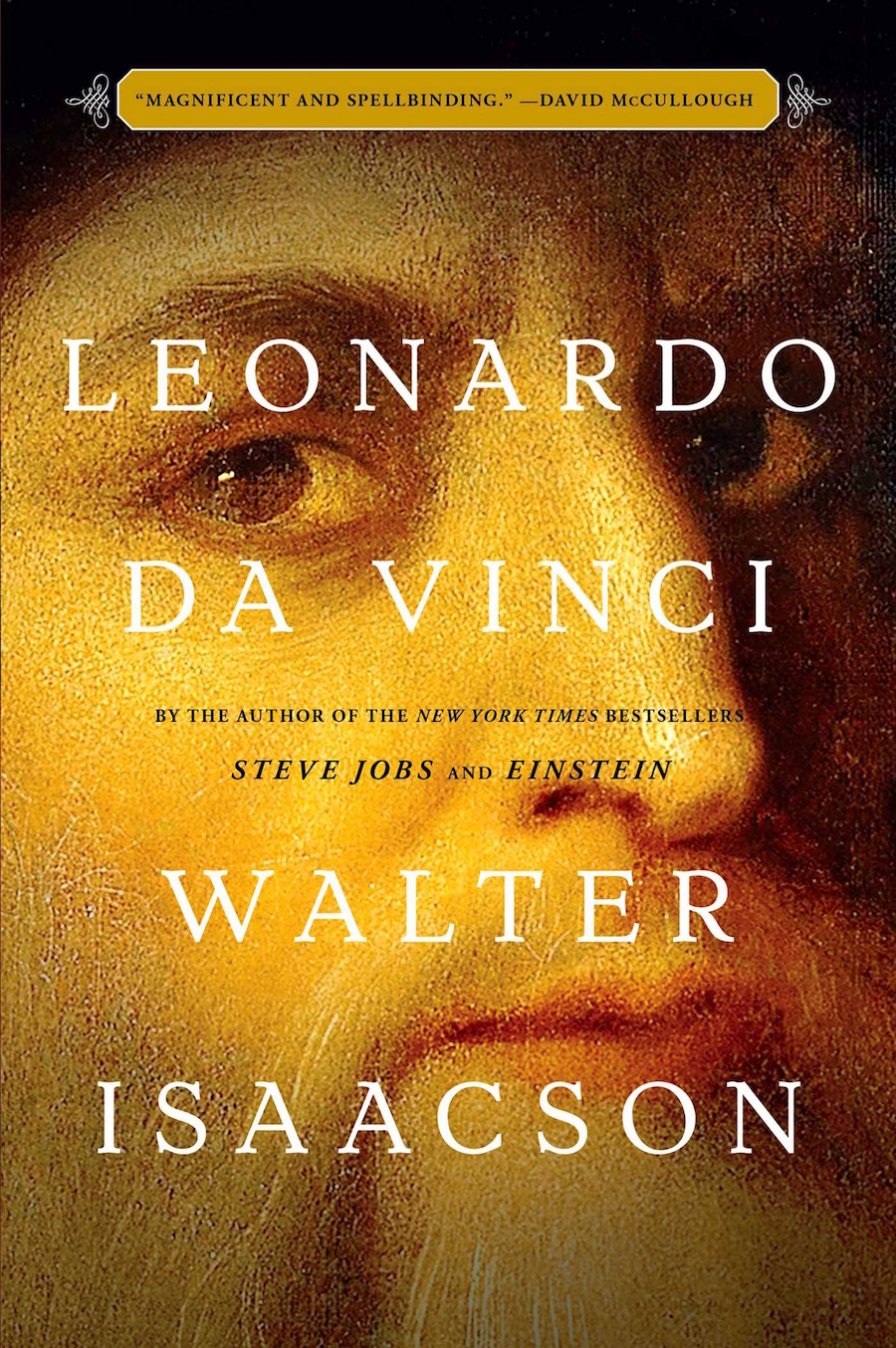

Leonardo da Vinci

Walter Isaacson

Simon & Schuster, 2018

624 pages

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Leonardo Da Vinci ~ an infinite curiosity - - Alejandra de Argos -