"The nerve pathways are something fixed, finished, unchanged.

Everything may die, nothing rebirthed "

Santiago Ramón y Cajal.

Frank O. Gehry in front of a blank page. The terrifying moment of creation. Feeling afraid, waiting for inspiration, stalled by emptiness. Nights of uncertainty. Conceiving an idea: suffering and ecstasy.

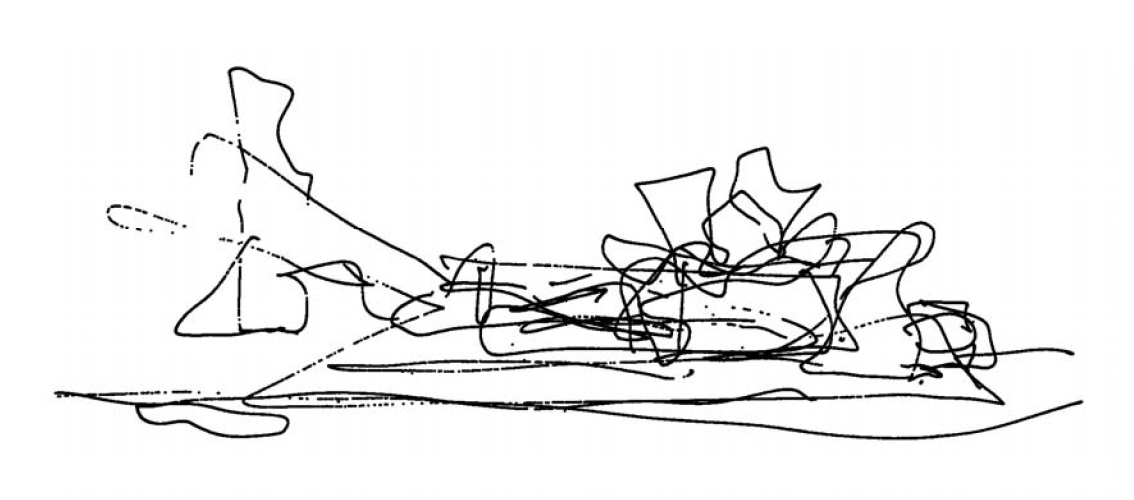

We are our brains. The mind is the result of dialogue between each of our hundred billion neurons. How would the impulsive lines of ink appear, led by the right hemisphere of the brain, where Gehry began to dance on paper in one long, winding movement to illuminate what would be the profile of the Guggenheim museum Bilbao?

We think in the head of a genius.

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain, 1991-1997.

Let us return to the illumination. It is the time when the paper of an artist begins to fill with projectiles: papers flying above the tables with crumpled despair; rough reports of more or less tight balls, containing unfinished sentences, ideas that were lost on the path from the head to the hand; sketches and drawings that do not work.

When Frank Gehry is asked where his imagination comes up from, he rests his pen on the desk, looks up from his glasses, and lets suspense fly in his studio until that gaze drops. Gehry is well aware of his Jewish ancestry, always down to earth, to reality, and says: "Inspiration is in that bin. Look in there, think of the caves, spaces, textures containing that trash". Much of his reflection is there. Writers, painters throw their errors into a basket. Gehry shows his, he wrinkles pieces of paper and transforms them into towers and palaces for music, hospitals made of metal forms that seem to melt under the sun, office buildings embracing dance.

He converts his dream ladder for Vitrainto into the same spiral, the life on a paper. Nothing dies: from the smooth wrapper leaf there is the outcome of a final sketch, to the less valued, relegated to the bottom of a trash can.

Lou Ruvo Clinic, Las Vegas, Nevada, United States of America, 2005-2010.

Frank Gehry (Toronto, 1929), winner of the 1989 Pritzker Prize, is probably the world's most wanted living architect. At 85 years old, he has become a total cultural protagonist. In Spain he has received the Prince of Asturias Award. In Paris, as well as the devoted retrospective to him by the Centre Pompidou, he inaugurated the new headquarters of the Louis Vuitton foundation and decorated the windows of their stores.

When in 1997 he completed the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao this architect-inventor-artist, who likes to say that many of the grooves are tribute to Don Quixote, found himself in a similar position to that of Miguel Ángel after his speech in San Pedro of the Vatican: revolutionist of contemporary architecture.

The strength of Gehry - described by the experts - lies in the motion that he embeds within the architecture, in his ability to create that movement from something inert. It is a contemporary cubism that serves to transform a line of twisted metal skin against the sky and glare of the sun, in a factory of feelings and infinite perplexity for its viewers.

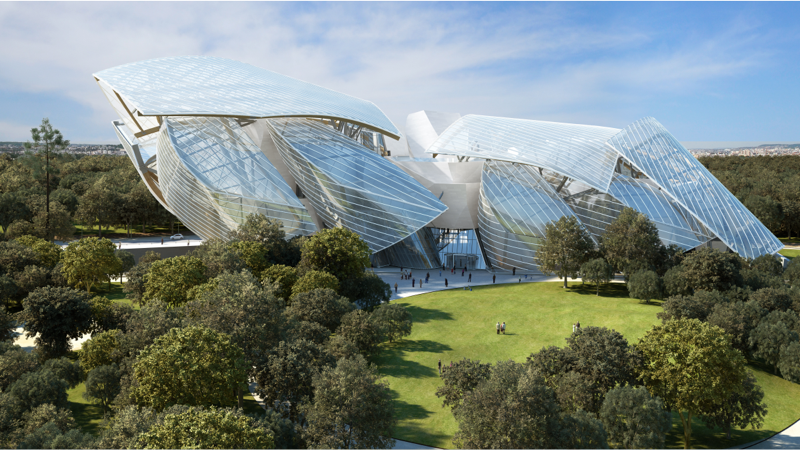

Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, France, 2005-2014.

Far from feeling that his career as an architect is coming to an end, Gehry recently shocked the world by presenting one of the most complex buildings of his life, another twist of his imagination: that capacity to lead the human eye to sensations, forms and alternative structures. On 27th October he launched his last sailboat: Louis Vuitton Foundation of the Bois de Boulogne, Paris, a developed building designed to promote culture and art, a great museum in which to present collections of permanent contemporary art, temporary exhibitions, entertainment... Bernard Arnault, chairman of Louis Vuitton-Moët-Hennessy, after visiting the Guggenheim in Bilbao, just wanted it to be Frank Gehry to draw his dream.

If Bilbao came from steel, Gehry does not disappoint here in his quest to integrate his buildings in the atmosphere and where they belong. In Bois de Boulogne, the weight of green, the tradition of the nineteenth century greenhouses and configuration of the nearby Jardin d'Acclimatation, 1860, Napoleon III, Gehry approached the pattern of a transparent building. As in Bilbao, there are many similarities: from the igloo to the cloud, to the wings of an insect. "Ultimately, beauty is in the eye" says Gehry, fed up with comparisons between forms and competition between limits of architectural sculpture in their designs.

There are 12 curved glass candles, with wooden gear, inflated by the wind which Gehry, in his passion for sailing, stacks without a hull under the Parisian sky surrounded by ponds and Indian chestnuts and spans the wind which seems willing to go flying over the Parisian mansard so admired by Gehry and whose impact can be followed at the Museum of Art Weisman, in Minneapolis, or the Stata Center, in Boston. "The history of Paris is the history of architecture," says Jean Nouvel.

More than 3,600 glass panels produce that feeling of transparence which integrate the inner and outer, constantly linking water, forest, the inside garden and producing continuous changes in the outside light: "Once we finished talking about the double skin, glass and iceberg, I likened the idea of composing a living façade, that would change, not only with light and shadows, but also with the ability to light up differently".

Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, France, 2005-2014.

Among his earliest memories, he must have been eight years old, Gehry clearly remembers his grandmother buying bags of chips for the stove. And again he returns to the feeling of happiness that those pieces of wood lying on the ground to build gave, apart from the worlds of cities and rings of roads. He enjoyed this in the same way that his memories took him to the times in which he painted alongside his father. At the age of 13, in the Hebrew school, he drew a picture of Theodore Herzl shortly which shortly after would be hung on the blackboard. The rabbi told his mother in yiddish that her son had goldene hänt: golden hands.

His studies of perspective, and later of ceramic at the University of California, pushed him towards architecture. From his time at university, he recalls how an afternoon of 1946 was at a conference that many years later would keep turning inside his head. The speaker was an older man with white hair: Gehry was fascinated by the power of design but paid no attention to his name. Years later learned that this was Alvar Aalto, the great Finnish architect whose work has influenced his.

During the 60s, in Los Angeles, he became involved in the California Art scene befriending artists like Ed Rushca, Richard Serra, Claes Oldenburg, Larry Bell and Ron Davis, later to discover the works of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. He envied them for their creative freedom.

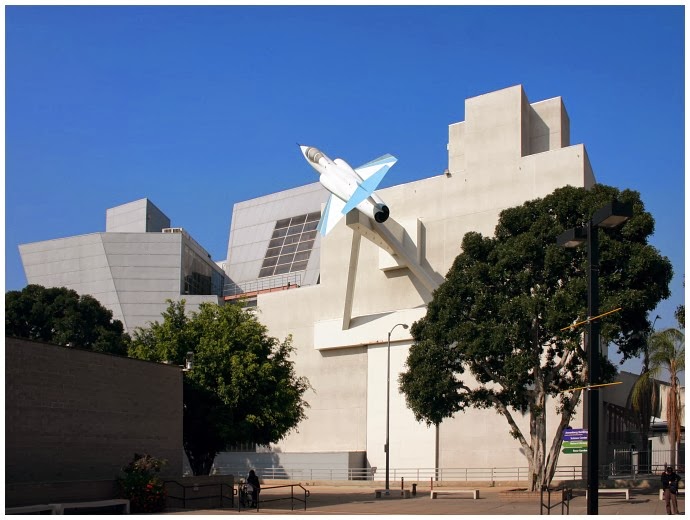

Aerospace Museum of California, Los Angeles, United States of America, 1982- 1984.

"Those artists did not feel bound by tradition, they were not out of a school, nor in the orthodox sense, deep intellectuals. They did what they wanted, manipulating materials, they had no boundaries," Gehry said. He came of modernism, a school of thought that mocks decoration. As a result of that, it was the materials that became his means of expression: he began using poor materials like cardboard - an influence of Rauschenberg-, corrugated sheet metal or chicken wire. Gehry wanted to convey this sense of newness and freedom in architecture. To try, risk, do something never seen before. He was considering the idea of mixing architecture without restrictions as concrete and immovable as the laws of physics. At this time he was mainly engaged in the design of housing within an architecture that has been called eccentric domestic.

Gehry Residence, Santa Monica, United States of America, 1977- 1978.

In the long documentary that Sydney Pollack does with Gehry on his life, there is a shot in which the two friends are talking in the kitchen of his home in Santa Monica. It was one of the highlights of his career. "When I bought it I saw that I must do something before we moved in. I liked the idea of leaving the house intact, and not changing it. It occurred to me to build another house around it. We were told that the house had ghosts. I decided they were to be Cubist ghosts. I wanted the windows to give the impression that they climbed from the ground". On the table they are speaking, the roof is broken into a large peaked window, and from there, at night, the effects of the car lights and traffic lights are distorted and the moon is reflected in the wrong place. He immediately began to hammer the roof of the bathroom, opening a gap with light as he could not see well in the mirror where he shaved.

Vitra Design Museum, Weil-Am-Rhein, Germany, 1987-1989, 2003.

Between 1987 and 1989 he built the Vitra Design Museum in Germany. It was a great break in his career, in a way, creating a new order. Gehry had planned an outdoor spiral staircase. He enjoyed the shapes he obtained by drawing but never thought they could be included in a building. He started playing with the staircase in the form of snake: he likened the contrast with the straight edges of the other volumes. He tried to express it through descriptive geometry but the construction was not accurate. He could not play with curved forms, he had to be restricted to the lack of freedom. The new movements he tried to express, took him to the computer. It is the 80s in California. And the outbreak of the software world came, of Steve Jobs at Apple, in his garage in 1976. In 1984 the company launched the Macintosh 128K, the first personal computer that used a mouse.

Parallel in time to the construction of Vitra, the Gehry studio was working on the project for the fish of the Olympic Village in Barcelona (1986-1992); a massive structure with sinuous stone forms, glass and steel. It was for this project for which they began working with CATIA, a computer program design, manufacturing and engineering by Dassault Systèmes to project complex shapes for the aerospace industry. This tool transformed the working system and Gehryś designs, facilitating the study of models with free and flexible forms and its projection in construction plans allowing it to be more daring, a little more and a little more... And so to support in its sculptural concept.

Bilbao, the Walt Disney auditorium, the building of DZ Bank... would not have been possible without this system.

GOLDBERG AND THE FISH

Gehry often described his work as fish. The idea of the fish is recurrent in his life and in his work, his sinuous curves appear endlessly in buildings, furniture and lighting designs. Its scales came one day by accident when working with a piece of concrete that fell and broke into pieces, those pieces made him think of the scales of a fish and since then he introduced them into his buildings.

"My colleagues were obsessed with Greek temples. You know, the postmodern era, in 1980 and after. Well, it was the great fashion, to reconstruct the past. So I thought: Greek temples are anthropomorphic. 300 million years ago there were only fish. If you have to go back, if one is so afraid to go forward, if you must go back, we can step back 300 million years. Why stay in Greece?" ... From then, he started drawing fish.

Fish lamp

In this way, the fish also became the memories of his toddler years. His grandmother bought carps that she kept alive in the bathtub of her home to prepare the gelfiltre, a traditional Jewish dish for the Sabbath.

The future Gehry, Frank Owen Goldberg, was the only Jewish child from school. From a young age he had to face the scorn of his peers. He was called fish face. In 1954, when he was 25 years old and had two daughters, he changed his last name to Gehry as he was pushed by his former wife, Anita, "It took me five years, when I was presented as Frank Gehry, I added, before I was Goldberg".

He also tells us about how he designed his own name, "Goldberg has, I'll draw it, a G descending, then o, l, d, b, e, r, g that goes back down. That is why Gehry has a G descending, and then e, h, r, with a y at the and end, also descending".

Growing up in a Jewish family and the study of the Talmud, the first expression is why?, it is the source that drives him to wonder every doubt in life.

With regard to image resource that comes into mind when thinking of his works, Gehry feels fascination for fabrics. The fabrics and its folds. In the early 90s, on a trip to Dijon in France's Burgundy, Gehry was fascinated by a stone fountain carved by a Dutch sculptor of the fourteenth century, Claus Sluter. In it,the monumental figures of the mourner's hooded monk sunder the tomb of Philip the Bold, causing him such emotion that he had to concentrate to study the chasubles that hid the heads of monks. The cloths eventually mutated to become the "horse head" of Gehry for the DZ Bank.

Claus Sluter, Tomb of Philip the Bold, Museum of Fine Arts, Dijon, France.

DZ Bank, Berlin, Germany, 1995-2001.

The influence of the weight of the fabric, its folds, are static; such as the tubular falls of the Tunic Charioteer of Delphi, or swollen by the wind, and the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa by Bernini, express not only the shape and movement of a rigid material, but - Gehry tries it - through those sculpted cloths, the expression channeled many emotions.

The Maggie's Centre was designed to recall the memory of his friend, the Scottish designer Maggie Keswick Jenks, who died of cancer in 1995.

This building is meant to be a meeting place for patients. It is the first building that, in 2003, Gehry projects in the UK. Seeing the sketches for Charles Jencks, husband of Maggie exclaimed: "This will be your Ronchamp" referring to the legendary Le Corbusier chapel in Franche-Comté. That ambitious comparison blocked Gehry who underwent a period of doubt and crisis in the rush of the plans. Until one day, Gehry himself says, that: "Maggie came to my dreams and said, 'Frank, what you did was a little extravagant". Thereafter, Gehry did not stop drawing. He found a sense of a building away from the spiritual connotations of Ronchamp, also more intimate: at the end of the day there should be a place where people go to feel comfortable and welcome "for a cup of tea and to mourn". So Gehry devised that tower as if it were a lighthouse and covered the main body with a corrugated roof. This time and for this coverage, his memory led him to take his trunk stored with images, a painting by Vermeer in which the undulating folds of her shawl reminded him of his friend Maggie.

Maggie's Center, Dundee, Scotland, 2003.

GUGGENHEIM BILBAO: CATHEDRAL OF THE 20th CENTURY.

The classic Greek spoke to us of the drawing, of the imago, the phantasma traced by the brush of fantasy, where the term comes to Castilian imagination. How was that day, at that hour, the head of Frank O. Gehry? What is surprising, says Frederic Migayrou, is his way of dreaming the work from scratch. Those early drawings, so mysterious, already contained a masterpiece. "Why did I have to spend two years designing a building that was already there?".

Gehry took Berta, his second wife, to Bilbao. Berta is Panamanian and Gehry wanted to dig into the bowels of the city, to find his character. She became his guide and his tongue to understand the Pais Vasco. He wanted to understand what was happening at the time. The Bilbao crisis, its economic decline, the disappearance of its shipyards...

Far from the light, Californian coast and urban, the first thing that puzzled Bilbao was its steel profile, their industrial cohesion mine, port, cranes, large ships coming and going, the trading. Everything seemed to colour the landscape in metallic shades, steel oxide clouds and mercury from its estuary. The reflections. The sounds.

Then, he did not stop until he knew something of its history, its art: the Basque architecture, political drama, terrorism. He fell in love with the city, its loyal people, the food, the pacharan and its green hills. They wanted to buy a house there, but were not well received. To the Gehry couple, Bilbao gave them the understanding that they were only interested in them to leave there museum there. No more.

Meanwhile, Gehry was dreaming of the building. He analysed the solar difficulty, wedged between the sea inlet, flown by the Salve Bridge. He wanted it to be "very Bilbao, very Basque, that hardness that I found so attractive". He had to leave the blackness of the estuary. The Nervion giant emerges from the waters as a fragmented spacecraft parts to fly with the wind of the Cantabrian Sea, luck of projection of a human dipper made of titanium tapes. After having climbed the hills surrounding Bilbao and having pointed out the exact location of the museum -"it must be there"-, Gehry looks at the place where the museum will be built, this time from the top of his hotel room. The journey begins from his head to the ink, from the ink to the titanium. His work is, as so often, intuitive. It is then when still on paper, with the letterhead of the Hotel López de Haro, he produces his first scribbles. The human brain is the most complex object in the solar system. Even today no one can explain how a kilo and a half of matter, protein and fat, can have ideas arise from it. From material to the immaterial.

Bilbao was a pioneer in building sailboats with a steel hull. The shipbuilding industry was based on steel. The Gehry museum resembles a futuristic sailboat floating on the river with all sails. Depending on the time of day, clouds, rain, night or sun, the building turns golden tones into silver tones. It is the effect of the titanium. Bilbao was, initially, designed in stainless steel. But all tests and models that were developed after the drawings did not give well on cloudy days. Against the grey sky of Bilbao, the stainless steel died in matt and dark tones. Back in California, Gehry found a piece of titanium in his studio that hung outdoors, when the effect of the rain turned it gold, as what happened in Bilbao, he cried out and gave an emphatic smile to heaven. This metal itself conveyed feeling.

With the Guggenheim, Gehry wanted to offer the city a new, eco building, which would be integrated into its own history and geography but would have a different impression. In which it would enoble the city and project an icon. "I think the communities crave an identity. The buildings have an identity in history. The Parthenon in Athens effect lasted for more than 24 centuries and lasts today. The Saint Peter in Rome has endured for more than five centuries. The people feel identified with buildings and return to them".

He would have liked to stay in Bilbao, contributing to the new design for the banks of the river. He had clear ideas, but he was accounted for. He had studied and understood the city and its architecture, he was not in accordance with the subsequent repercussions around the Nervion. It seemed that the true Basque spirit had not arisen: all those gardens, these excessive lights that had nothing to do with the merits of the Basque soul. Frank Gehry left part of his heart in Bilbao. Years later, looking at those first drawings he surprised himself: "One may recognise the signatures: at the end of this building comes from me. But this is different to everything I have ever done." Perhaps that is it.

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain, 1991-1997.

INTERVIEW WITH FRANK O. GEHRY

M.V: Most of the buildings are constructed from metal: the world of reflections, changes in light, night and day. The headquarters of the foundation Vuitton is another example, this time, transparent. You no longer build only in brick or stone.

Over the years your buildings reflect light, they absorb. What mystery transmits the light?

F.G: Natural light is free so I always say we should use it. We know the path of the sun and the moon and we know how light plays with shapes, building shapes. I don’t know about the mystery part.

M.V: What is your favorite moment in the process of creation, the most exciting? Is it the first drawing, the final model?

F.G: Working with the client to understand their needs, their dreams and to help them realize it. The technical stuff we do brings care in constructability: from care in budget control, care in responsibility to energy issues. We also respect neighbors and work with contexts.

M.V: In the history of architecture, religion also claims its space. In Spain, we have examples like Córdoba: on a Roman temple a Visigoth church is built; on this, the Omeyas construct the actual mosque; and early sixteenth century, a Christian basilica was added to the Muslim center construction. In the early years of Frank Gehry, a large space is occupied to Hebraic studies and patient Talmud reading. Among his buildings there are auditoriums, hospitals, warehouses, banks and especially museums.

Would you have liked to face a great religious monument?

F.G: Yes!

M.V: Julian Schnabel, his friend, says that Bilbao has the proportions of Luxor.

Have the architectural proportions varied since then?

F.G: Yes. That architecture exudes power. Today we try to exude friendship, community, and positive feelings.

M.V: Your creations seem to ride more and more towards lightness: do you remember Don Quixote, charging at a gallop against windmills 1991-1997. Its buildings are wrapped by metal sheets or candles that go out flying. We think the 12 candles of Paris, or in the Rioja winery as the headdress of a woman made of metal coloured ribbons that can fly among the vineyards. You are an admirer of Bernini recognizing the way which his paintings seem light, malleable, overblown by the wind: the Ecstasy of St. Teresa.

Will this architecture endure this obsession? Up to what point, for you, is lightness inseparable of beauty?

F.G: When it loses gravitas.

M.V: It has been over 20 years since the Guggenheim of Bilbao was built. You have created the museum and have converted it into the symbol of the city, the great transformer of Bilbao. The locals have been given the luck of the identity with its Guggenheim museum.

What is Bilbao for you today?

F.G: Bilbao is a place I cherish. The work led me to many friends. The one person who seems to be left out of all the questions is Tom Krens. Tom was director of the museum, was my partner in developing this project and deserves a big credit for his vision and his trust in me.