Damien Hirst (1965) began his artistic career as an iconic member of the Young British Artists group. The advertising mogul and gallery owner Charles Saatchi raised this group to the heights of world recognition and made Hirst its foremost representative, by funding and supporting his career. He was the one who managed to sell - in 2004 and for 9.5 million euros - Hirst’s tiger shark preserved in formaldehyde. This particularly representative work forms part of his Natural History series, along with his cabinets of fish in formaldehyde.

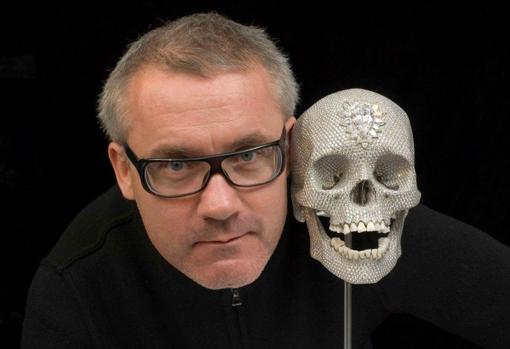

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

Damien Hirst (1965) began his artistic career as an iconic member of the Young British Artists group. The advertising mogul and gallery owner Charles Saatchi raised this group to the heights of world recognition and made Hirst its foremost representative, by funding and supporting his career. He was the one who managed to sell - in 2004 and for 9.5 million euros - Hirst’s tiger shark preserved in formaldehyde. This particularly representative work forms part of his Natural History series, along with his cabinets of fish in formaldehyde. In these works, he sets a feeling of permanence, generated by his meticulous scientific organisation, against the ephemeral nature of life, which he also does with the minimalist style dissected cows and calves displayed at Tate Britain, which won him the prestigious Turner Prize in 1995.

Other important series of Hirst are his widely recognized Spot paintings: same-sized dots in random colours, named after pharmaceutical narcotics and stimulants. Or his Butterflies, named after a psalm that touches on Hirst’s favourite themes: life, death, art, beauty and spirituality. The mystery of death is shown through the final transformation of the caterpillar into a butterfly, a symbol of the soul since antiquity, also seen in the rose and stained glass windows of cathedrals.

The Medicine Cabinets are yet another example of the philosophical concerns of Damien Hirst, an artist who has experienced the abyss of drugs, alcohol and tobacco, and who views art as therapy. Art, together with science is a social phenomenon of life in motion, a way of reflecting reality throughout history. In our current era, characterized by the triumph of technique, Hirst has succeeded in making his works into icons of contemporary art.

Alain Dominique Perrin, the creator of the Cartier Foundation, is holding Damien Hirst’s first exhibition in a French museum. We are referring to Cherry Blossoms, which displays 30 of the 107 works created by the artist over the last 3 years.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

You have recently gone back to painting. Has the fact your mother painted, in some way, determined your artistic career?

I suppose so, yes. Obviously, I already had a certain artistic instinct, but my Mum strengthened it when I was young, she encouraged me to draw and paint. I remember she would sit me in a corner with a pen and paper and when I would say I had finished the drawing, she would stick more paper to it again and again. Ultimately, I think it was a good thing, which helped me to think big.

At what age did you realise you wanted to be an artist?

It is difficult to say exactly when. I grew up in Leeds, Yorkshire, North of England, where nobody I knew was paid to do a job they enjoyed, rather, they would work for money doing any old job. For example, my Mum worked in an office and my Dad was selling cars for a big company. So, the idea was that a job was to earn money and your life was separate. With that in mind, because I enjoyed drawing, it never really occurred to me it could be a career possibility. I thought about becoming an architect as it allowed me to incorporate my passion for drawing, but it didn’t work. I was very messy when I was an architect. I signed on at the job centre when I finished my studies and that is when I had the idea to go to Art School. To be honest, the idea to become an artist came to me as a bit of a shock and it was only really at Art School that I realised it was a possibility.

At 16 you visited the anatomy department of Leeds Medical School to make life drawings. Death and decadence are themes that are repeated in your work. What meaning does death have in your work?

It is a complicated issue. I used to think that you could make art about death, but I don’t think you can anymore. Death is not art because art is life. I think I have changed as I have got older. As a human being, I want to confront things I can’t avoid. Death is one of those things. When I make art, I want to deal with those issues. That is the essence of art. Art deals with death. I think art is a light in the darkness.

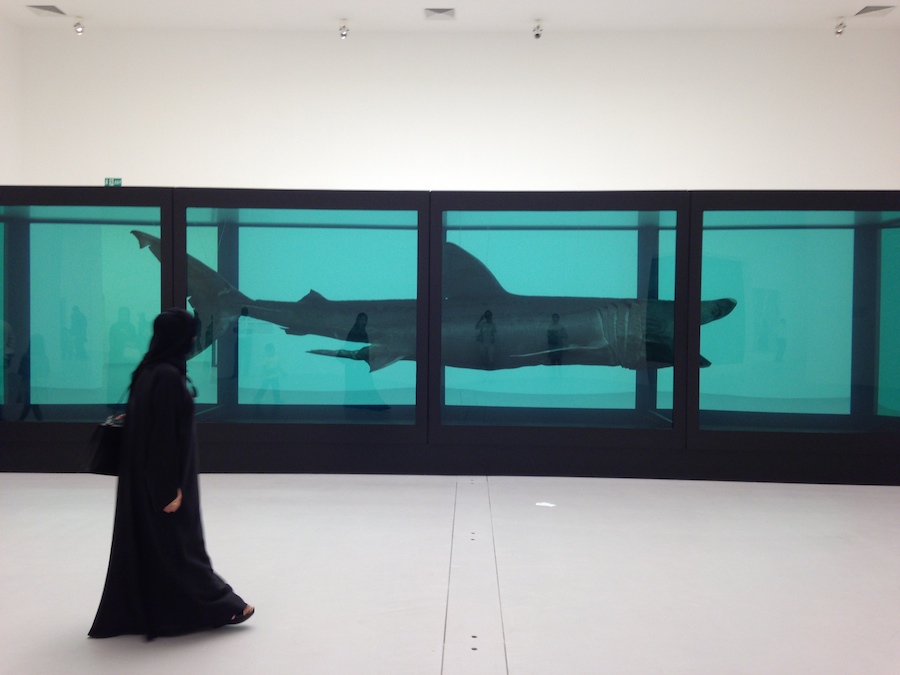

Damien Hirst, Relics, Doha. Photo: Elena Cué

Can you tell me about your exhibition Cherry Blossoms at the Cartier Foundation in Paris and if the pandemic has affected your work in any way?

Absolutely, I think they are pandemic paintings. In my case, it got to the point where my work was very solitary. Before the pandemic, I dedicated 10 years of my life to Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, which involved working closely with many people, teams and fabricators. It involved very complicated things with different nuances in motion. After, I went on to paint with a few assistants. Then, I started working in a small interim studio just before Covid and when the pandemic hit; my assistants had to leave because there wasn’t any work. I began painting in solitary. Actually, I was very lucky to have the studio because when Covid came, I did not have to stop painting. Cherry Blossoms is a result of that. It is somewhat strange that such darkness brings such light and brightness. In reality, hope is one of the key aspects of the painting. When you are feeling hopeless... We have all felt and still feel great fear. Fear has a fundamental role when you want to make hopeful paintings. I honestly think it came out of that.

You studied Fine Arts at Goldsmiths College of Art in London. What was the most important thing you learned about art there?

I learned so much. One of the most valuable lessons was that there are no rules. Once I made something that was very confrontational and messy, I just screwed things together randomly. It was half-sculpture, half-painting, crazy thing. I remember the tutor saying it was not very good and I told her that that was the point. She then said that I needed to be clear with my work, to which I replied that was the point, I was not being clear. In the end, she agreed the only worthy artists are those who sack off everything for their convictions. In that moment I thought “That is it.” That was another key lesson. The teachers at Goldsmiths were all working, well-known, established artists. In many Art Schools teachers are failed artists who tend to teach what art means through a very negative perspective. That is why, studying at Goldsmiths was so incredible, there you were treated just like any other artist. From day one they trained you to go out into the world. They also taught you other aspects of the art world, not just its function. We were forced to justify everything and question everything. That was really important.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

In the 80s, you and some other students organised the Freeze exhibition, which caught the eye and financial support of the publicist and gallerist Charles Saatchi who, along with the Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy in London, elevated the group of Young British Artists. What did this collaboration mean to you?

There was a lot of exciting art at our college but there was not a place to fit it into the art world. We knew that no gallery wanted us, so we decided to create our own gallery. That was a turning point. We thought that we stood more chance as a group than every man for himself. It was a really exciting time. One of the lessons I learned at Goldsmiths is that you cannot paint, put your painting in a corner and wait to be discovered. You have to be more proactive. I wanted an audience and I had to find it. At Goldsmiths I realised you should not wait.

Do you miss collaborating with other artists?

I still have very good friends from those days. All the artists in that group were amazing, like Sarah Lucas, a phenomenal artist.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

Your admiration for Francis Bacon in your early days is well known. You stated that you stopped painting when you realised that your paintings were “like bad Bacons”. Which artistic technique do you feel most comfortable with now?

I enjoy painting a lot more now. I had a fear of painting. It was a question of confidence. There were two problems: one was a lack of confidence and the other was that painting was no longer fashionable and involved many challenges. Today it is very exciting, much more accepted. Back then painting was frowned upon, it was very old-fashioned, and I was desperate to be innovative and revolutionary which I could not achieve by painting. That is why I came up with the Dot Paintings, which ended up being very different from Bacon. In my heart lies the same kind of darkness that I really like in Bacon, Goya, or Soutine. Since then, I have managed to find my own way to paint, and I am very happy with that. I remember when I was a student, I used to paint and wonder about what people would think of my paintings. I would never really get involved. Whereas now, I just don’t even think about it. Someone once told me the real tragedy in painting is much more intense than that in real life. Just painting and playing with colours, I really feel the highs and the lows of existence. It is a new place for me, but I am very comfortable there. Just like Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable which is a very traditional exhibition, but it is actually very conceptual. Like my last show at Claridge’s, The Pipe Cleaner Animals, which I am very happy with. It is so childish, fun, and amazing.

Which part of the creative process excites you the most?

The end. I enjoy the technology, people, and machines but I like objects in an empty gallery.

The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, Damien Hirst. Relics, Doha. Photo: Elena Cué

At the beginning of the 90s your work The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, a shark submerged in formaldehyde, marked the start of your Natural History series, a totally revolutionary concept in the world of art. How did this idea come about?

Most of my ideas come from the desire to describe a feeling. I was looking for an object to symbolise a feeling. I had seen Richard Serra’s sculptures at the Saatchi Gallery. They were enormous steel sculptures. I remember walking between them, thinking they could fall on me at any moment. I remember feeling afraid and running out. I was fascinated by the fact that a sculpture could provoke fear. It invites you in to then terrify you. This was the root idea. I was inspired by a lot of minimalist artists like Carl Andre and Donald Judd. I loved Sol LeWitt’s Boxes (Project Box, 1990). I wanted to create a piece similar to that of Sol LeWitt but with something real at the centre. That is how the idea was formed. I wanted a real shark, big enough to devour a human and incite terror. Those were the ideas buzzing around my head and that is how this work came about.

Damien Hirst, Relics. Photo: Elena Cué

With the Medicine Cabinets series, you commented: “science is the new religion for many people”. What is your religion, what do you believe in?

My questions of belief have perplexed me for years. It is very difficult to find something to believe in and it is very difficult to live without having something to believe in. My exhibition Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable was specifically about faith and the search for truth in a world of lies. I was brought up in a Catholic family until I was 12 years old. Then my mother got divorced and she could not practice anymore. Right when she needed it the most, it let her down. That is why I gave up on being Catholic at age 12. With time, I realised that concepts like God are very complicated for me. I believe there is nothing. I prefer the scientific approach. I like science, but it fails in the same way religion does. Religion gives you almost everything you need. Money is the bane of religion. That said, my belief in art is almost religious. I believe in magic through art. Any kind of magic is a religious act. If you believe in goodness or in hope, if you believe that hope can conquer fear, you have religious thoughts. I believe in art, where one plus one can equal four, five, six, seven or anything. Thanks to art, you can create much more than you have. So, I suppose those are my beliefs. It is hard to say I do not believe in God. I believe in art because it is very similar.

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

In science, what is allowed today might be the mistake of tomorrow. Science progresses but art doesn’t...

I think science offers an incredible way to view the world, but it is not the only one. In my opinion, it lacks the emotional part. We need emotions in order to survive. Scientists are not emotional enough and religions are the exact opposite. We need a mix of both. It is funny, both science and religion use art in the same way that governments do, to sell their ideas. There is no way to sell an idea without art. Just look at all the art that was made because of religion. Even in science, pills have to have the correct shape in order for us to believe in them because if each of them had a different shape, nobody would believe they have the same effect. Everything must be sterile and perfect, perfect shapes, perfect colours and perfect packaging in order for us to believe that science helps us fight against death. That is basically science. Science is a religion that declares it can stop death. In my opinion, science offers us immortality and religion offers us the afterlife. Although, in the end, they are both bullshit. As for art, it doesn’t offer you anything you do not have, it offers you something that already lives inside you. That is the difference between art, science, and religion.

Damien Hirst, Relics. Photo: Elena Cué

Walking in Paris, Cartier Fondation, Damien Hirst, Cherry Blossoms, Paris 14th, july 2021

Damien Hirst, « Cerisiers en Fleurs » – Le film documentaire

Damien Hirst with The Currency artworks, 2021. Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd, DACS 2021.

- Interview with Damien Hirst - - Alejandra de Argos -