- Details

- Written by Clelia

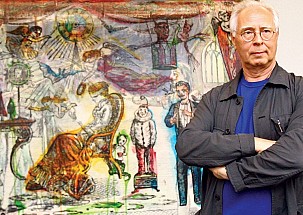

The sculptor and painter Antoni Tàpies was born (Barcelona 1923) into a well-to-do Catalan publishing dynasty and it was here and how his love of reading started. Lung disease left him unable to continue his law studies but did allow him to exhibit circa 1940, in what turned out to be the start of a long artistic career, his earliest pieces which featured mainly graphic art. Due to the destruction wrought by the Second World War and the impact of the atomic bomb, he expressed, through innovative new techniques, his interest in dust, earth, matter and atoms, all elements that became intrinsic to his later textured paintings. Heavily influenced by Klee y Miró, his iconographic compositions increased to now include greater expressivity and communication using dense textures as well as some geometric elements.

The sculptor and painter Antoni Tàpies was born (Barcelona 1923) into a well-to-do Catalan publishing dynasty and it was here and how his love of reading started. Lung disease left him unable to continue his law studies but did allow him to exhibit circa 1940, in what turned out to be the start of a long artistic career, his earliest pieces which featured mainly graphic art. Due to the destruction wrought by the Second World War and the impact of the atomic bomb, he expressed, through innovative new techniques, his interest in dust, earth, matter and atoms, all elements that became intrinsic to his later textured paintings.

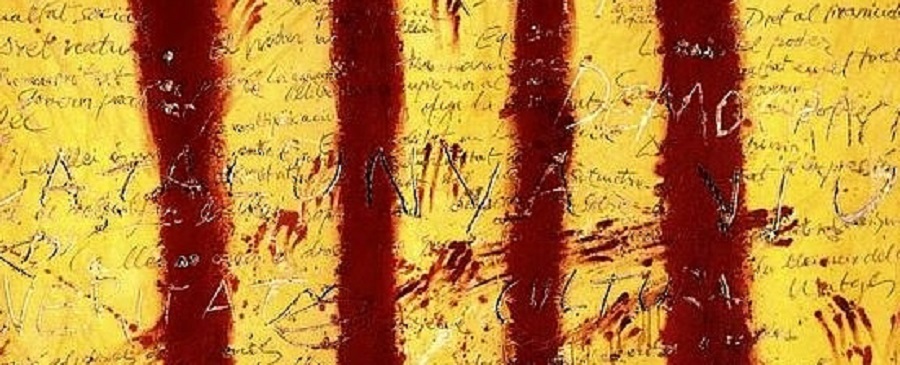

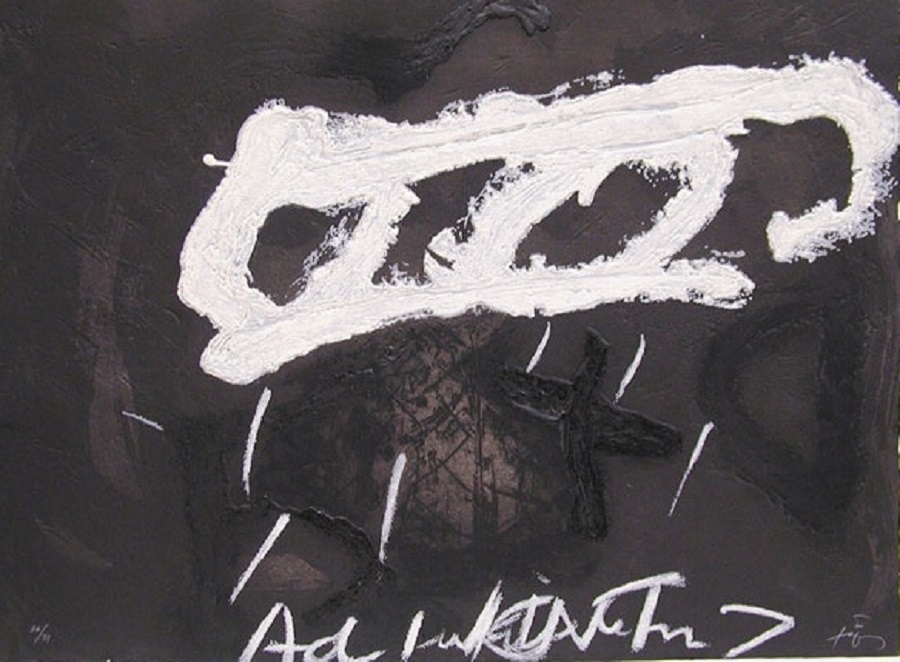

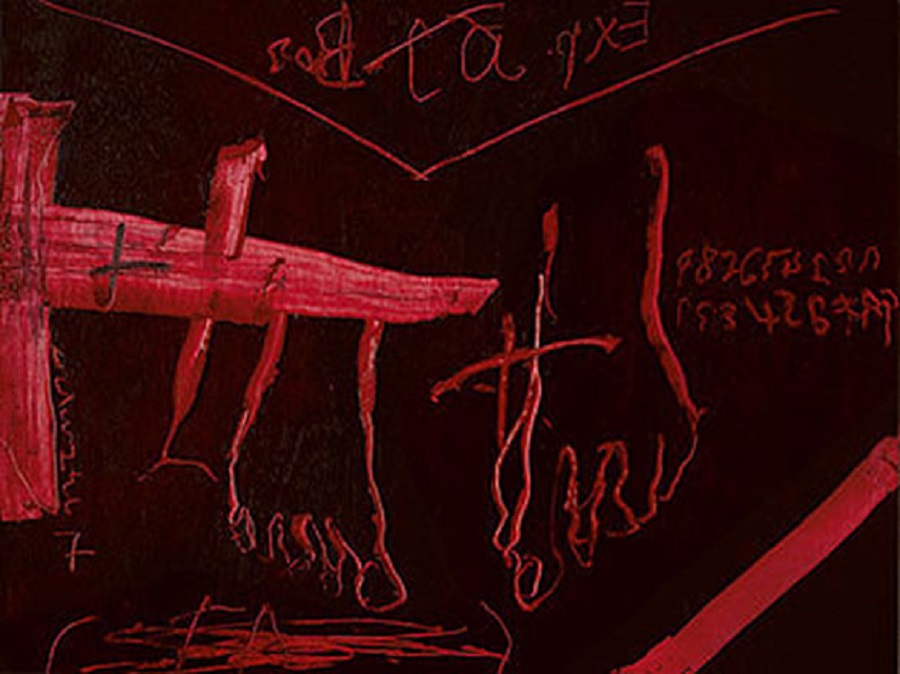

"Grattage Rojo" (Red grattage). Image available at www.tiempodehoy.com

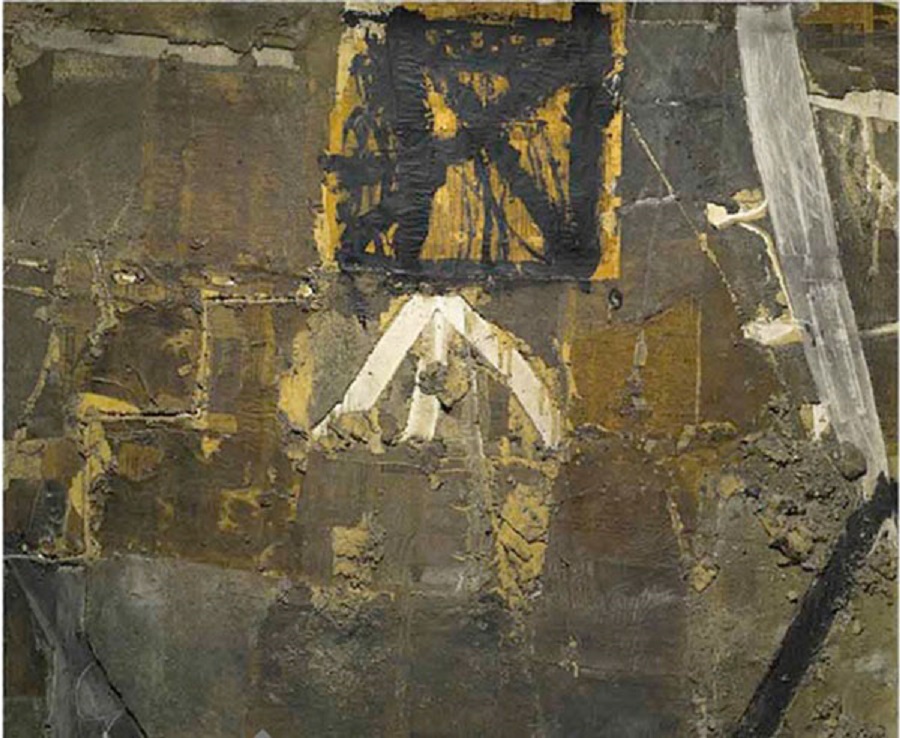

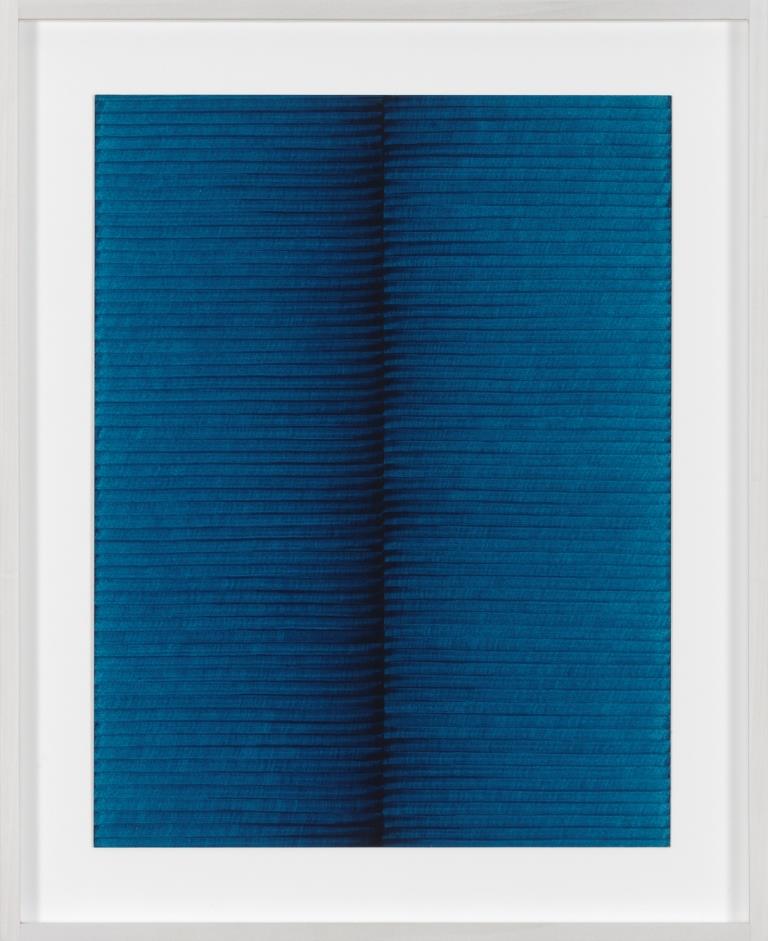

"Azul LXIX" (Blue LXIX). Image available at www.tiempodehoy.com

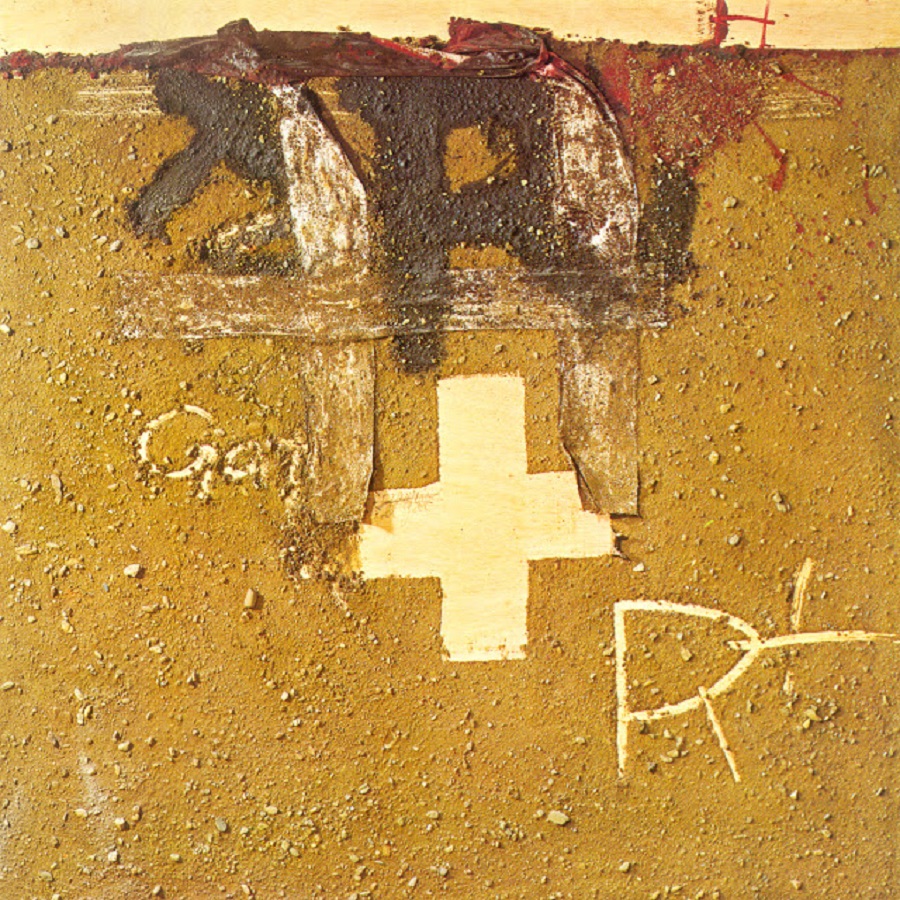

"Cruz y Tierra" (Cross and Soil). Image available at www.repro-arte.com

{youtube}K3pbV4GmDLA|600|450{/youtube}

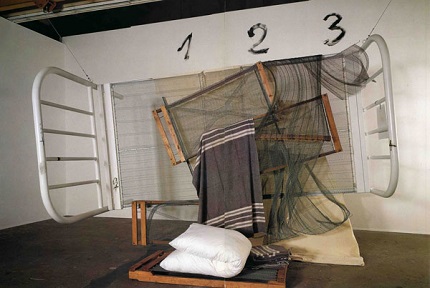

Image (right): Bed, available at www.tallerdecartasdeamor.wordpress.com

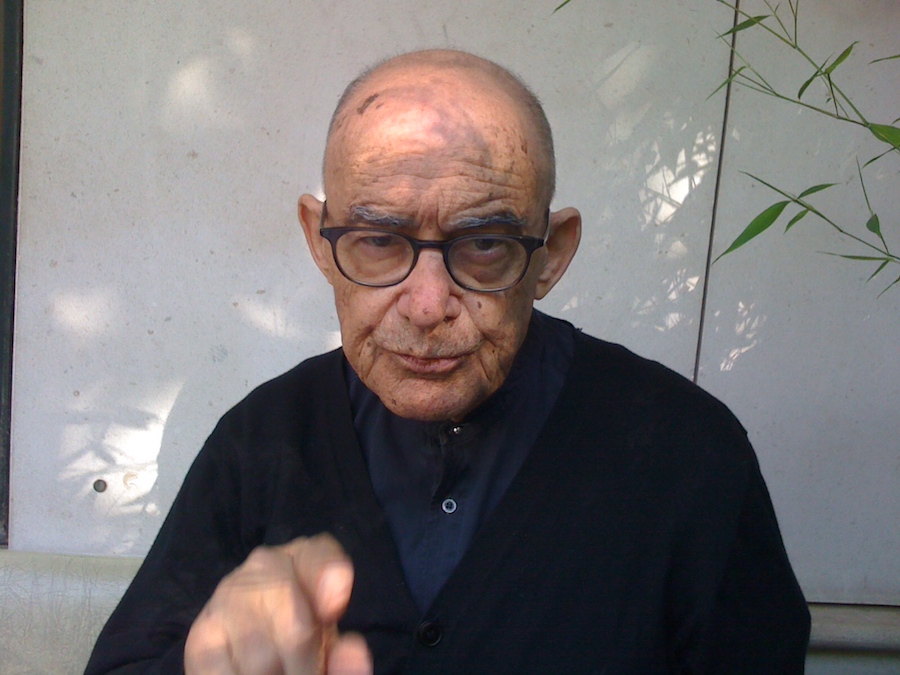

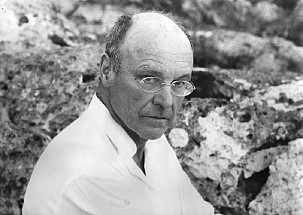

Image: Antoni Tàpies, available at www.trianarts.com

Image: Antoni Tàpies, available at www.trianarts.com

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Antoni Tàpies: Biography, Works and Exhibitions - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Maira Herrero

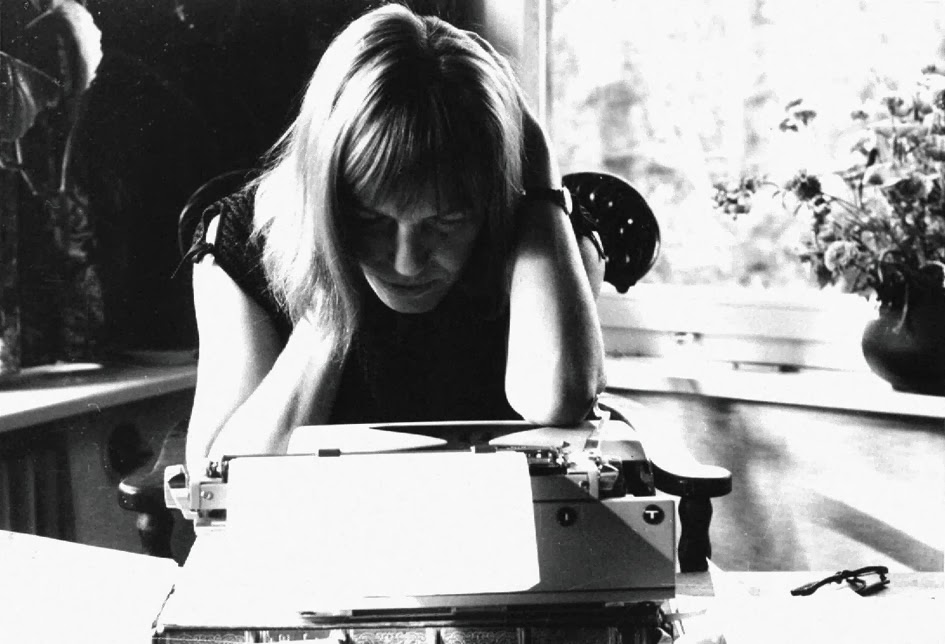

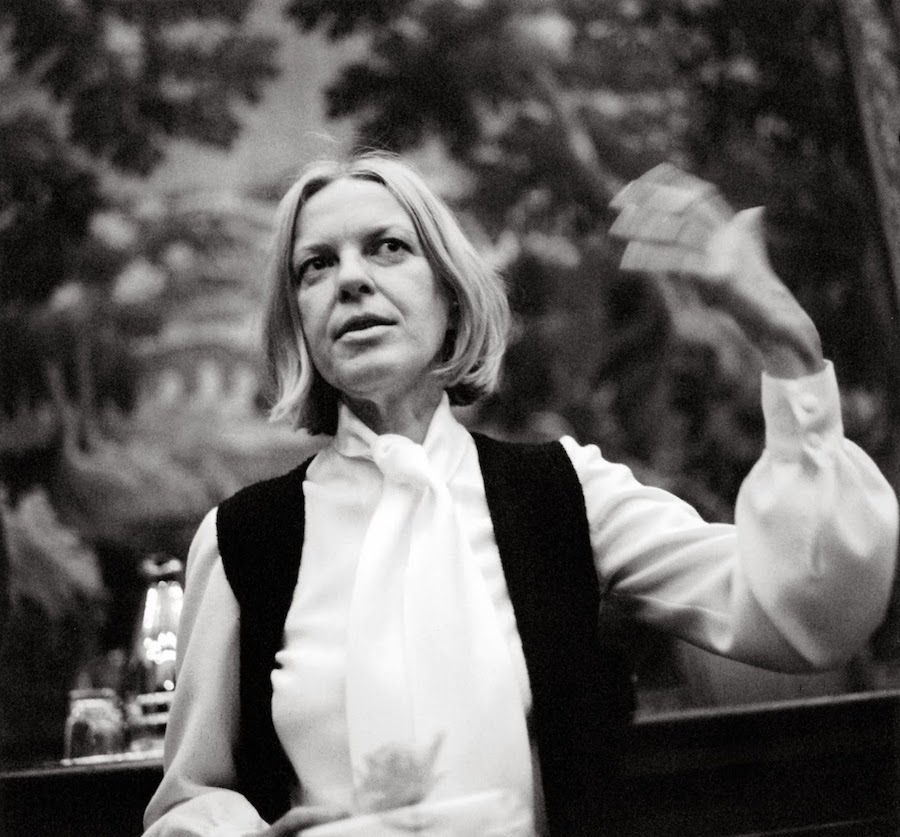

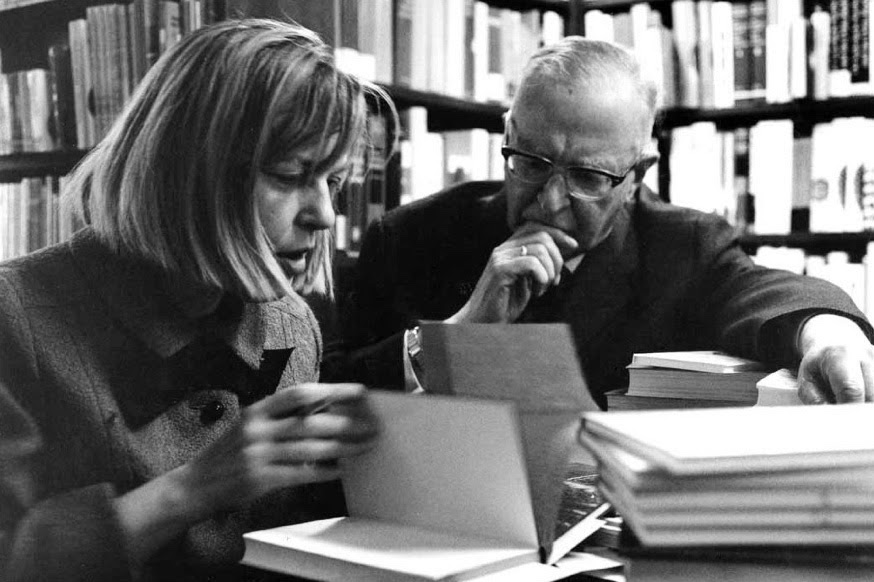

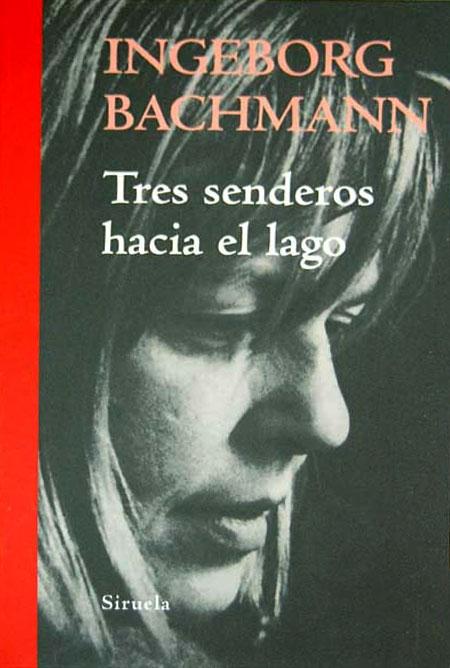

"The most intelligent and most important poet our country has produced this century has died, in hospital in Rome, as a result of the burns she suffered, apparently, at home in her bath according to the Italian authorities' investigations. I have travelled with her and during our travels, she shared many of her philosophical opinions as well as her concerns about the way the world was heading and about the course of history, both of which frightened her throughout her whole life." With these words, Thomas Bernhard summed up the death of his dear friend, Ingeborg Bachmann. Bachmann died on the 5th May 1973 of burns sustained during a fire at her house in Rome. She had chosen to settle there definitively in 1969 for its Southern European warmth and sunlight.

|

Author: Maira Herrero, |

|

"The most intelligent and most important poet our country has produced this century has died, in hospital in Rome, as a result of the burns she suffered, apparently, at home in her bath according to the Italian authorities' investigations. I have travelled with her and during our travels, she shared many of her philosophical opinions as well as her concerns about the way the world was heading and about the course of history, both of which frightened her throughout her whole life." With these words, Thomas Bernhard summed up the death of his dear friend, Ingeborg Bachmann.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- Three Paths To The Lake by Ingeborg Bachmann - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

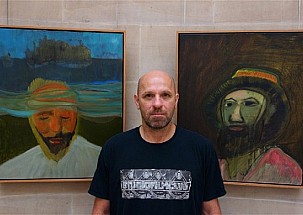

The art of Lita Cabellut (Barcelona, 1961) is pure feeling, like the haunting voice of flamenco singer Camarón de la Isla whom she so greatly admires. The colossal format of her paintings and subjects, whom she endows with great psychological potency, are the clamor of an artist who needs her voice to be heard. Her work exudes the wisdom of life that runs through her gypsy veins. She portrays souls with expressionist strokes that spring from forces underlying all thought. Their gaze is by turns defiant, nostalgic, beseeching, proud, sensual, wise… Every portrait tells stories: the stories of the artist, our own, and universal stories of the human condition. Gaze, gesture, and skin convey the scars of life’s wounds but also all its beauty. A constant dichotomy exists in her life and work: the formal and the wild, light and dark, reason and passion, but always there is beauty.

Author: Elena Cué

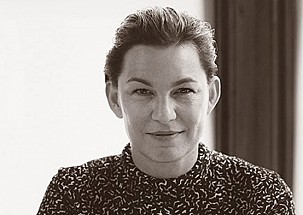

Lita Cabellut. Photo: Elena Cué

The art of Lita Cabellut (Barcelona, 1961) is pure feeling, like the haunting voice of flamenco singer Camarón de la Isla whom she so greatly admires. The colossal format of her paintings and subjects, whom she endows with great psychological potency, are the clamor of an artist who needs her voice to be heard. Her work exudes the wisdom of life that runs through her gypsy veins. She portrays souls with expressionist strokes that spring from forces underlying all thought. Their gaze is by turns defiant, nostalgic, beseeching, proud, sensual, wise… Every portrait tells stories: the stories of the artist, our own, and universal stories of the human condition. Gaze, gesture, and skin convey the scars of life’s wounds but also all its beauty. A constant dichotomy exists in her life and work: the formal and the wild, light and dark, reason and passion, but always there is beauty.

We begin our conversation in her studio and home in The Hague.

Elena Cué: You were abandoned by your mother just months after you were born, taken in by your grandmother and lived on the streets of Barcelona until you were adopted at age thirteen. You knew you wanted to be an artist at that age, when your adoptive family took you to the Museo del Prado for the first time. In your earlier life, before you began to paint, how did you channel your artist’s energy?

Lita Cabellut: Through fantasy, I think. You aren´t aware of what you are living or doing at the time. But what I do remember is that I was a ghost: I sold stars, for example. Now I think about it, and the artist was already present. Though of course, talent that isn´t developed doesn´t grow.

What do you think art is about?

It’s a way of conceiving, seeing and feeling about life. Art is much more than material. It is a great empathy for the world, for life. That is what art really is, because much of it is ethics, and fundamentalisms. It’s unavoidable: freedom and dictatorship at the same time, life and death. It’s so complicated and so simple at the same time. We always want to idealize art, isolate it, and make it individual.

Which it isn’t.

Which it isn’t, and that’s why art is suffering right now. We’re determined to isolate it and make it individualistic. Plato said that beauty was love materialized. I think that´s sort of it. Art absorbs, because it is a constant death and rebirth in the same day. You have to give it everything, and that’s why there’s a lot of risk in my work. The line between good and excellent is so fine, and that excellent has a risk. Not to be better, but to overcome what you don´t know. When we love and cherish what we don´t know, that´s when we start to understand what art is. Because art is ugliness as well, and it is beauty, and hardness. Art is velvet on the outside and bleach on the inside, because it burns you.

Lita cabellut. Impulse. Courtesy of the artist's studio.

Why did you choose figurative painting as a means of expression and focus on portraiture?

It´s an obsession. In reality, my great passion has always been psychology. When I was a small child I was already aware that by studying people you could prevent calamities. I knew very well what my next three hours were going to be, what the situation might or might not be. And then that turned into a form of survival, and then a way of living. What interests me most are human beings, because humans are so complex, so beautiful and ugly at the same time, so much so that it is fascinating. So I began to pay attention to figurative artists, and then I switched over completely to Saura, Tàpies and abstract artists. And you can see it in my work. It’s a communion of figuration and abstraction.

What is the importance of abstraction to you?

Abstraction is very important to me. I went back to the museums, to study Velázquez, Goya... I realized that they were the great abstract artists, and that they used it as a means for illusion to give form to a figuration that did not exist. That´s when I began to see abstraction as interesting, from that philosophical point of view. The great masters use figuration as an illusion of something that doesn´t exist and that our brain finishes. For example, if you look closely at a clothing in Velázquez, with its cuffs and fabrics, it’s totally abstraction. It´s an illusion of what you are seeing. It is points of light, of matter, placed in such a chaotic and anarchical way that from a distance they form an image that forces you to see. So if the artist has the power to manipulate the eye of the person who is seeing, and takes the eye to another place where it would not normally see, that’s art. That seemed very interesting to me, and I began to use figuration much more. At first without faces, just bodies. Because I wanted to study position for people to see gesture.

Lita Cabellut. Photo: Elena Cué

How do you choose your subjects?

They´re models. But first is the theme. I always work by themes.

And how do these themes come up?

For example, the trilogy of doubt came to me one night when I was talking with a friend who told me that she was having a legal problem. And I thought, there is so much doubt in knowing who is right, and truth is so difficult to find. And suddenly the title came to me: the trilogy of doubt. It will be about power, impotence and ignorance. Because through ignorance, tremendous things are done.

And in what way are you in each one of these portraits?

All portraits are great self-portraits. They are a way to relive distant, hidden, present and latent emotions every time. Every portrait is me. In the trilogy of doubt, where there is the great dictator, a victim and an ignorant, I’m all three. When I paint, I am in the painting. It´s me. You know what happens? You can only paint or create what you know. Empathy happens because we recognize ourselves in something. We cannot feel something we don´t know. It´s impossible, just an illusion.

Is art a cure or a palliative?

It´s difficult for me to imagine life without art. It´s as if God had turned out the lights of the world. The sadness I feel at living without art is so deep that it makes me dizzy. Art has cured me a lot. I am a happy woman, so to speak, of course. But I am a woman who lives, and I love life, and my children, and I love who I am and what I am not. I see possibility in everything. I owe all that to the possibility of dying every day and being reborn: I’ve been able to do away with so many things that weren´t good for me, so many emotions, and give that form in these images.

Lita Cabellut's studio. Photo: Elena Cué

Has art helped you forget or remember?

I’d say acknowledge. Provide a place. Listen, for example I painted monsters, images that were monstrous. I painted everything that frightened me and was still in my subconscious, and would suddenly appear like a capricious dog that sits in an unexpected spot. Feelings and images would come to me that I didn´t know what to do with. These days I don´t title my works, though I used to, because I wanted to identify them, I wanted to see all of those feelings. And it´s really interesting, because once you give those names and see them, they become very small. The more intelligent you are, the more fears you have. For children, who dream about that, it´s a kind of active intelligence. There is so much risk in the world, so many dangers, that intelligence needs to calculate those dangers in order to survive. It´s the law of the strong. I´ve always had many fears, like not being able to sleep with the lights off. Now I sleep with the lights off in the house, but not in the garden.

In other words, you’ve been getting rid of those demons through art, by giving them form and getting them out of your unconscious…

Exactly. I´ve been able to paint it all: ugliness, cruelty, tenderness, all of those elements… You have to think that you´re like an octopus, with tentacles that need to touch all kinds of emotions. If you are unlucky, some of those tentacles will be stunted, because they haven´t been able to recover or have not had the right space. I´ve been able to use them extensively in my own work. I´m certain that are has cured me. I have a foundation for children so there can be art. Because I´m absolutely sure that art goes much further than psychiatric methods. These are necessary as well, but art goes much further.

Art... and love?

I remember when I was small how difficult not feeling loved was. It was really tough. I’m a mother and I know what that is. No one can imagine how important the love of family is for so many things to grow. It´s true that tragedy, for artists, is like a box of jewels. You can´t paint suffering or pain if you haven´t lived it. It will always be an imitation, a caricature.

Lita Cabellut. Silence of the white. Courtesy of the artist's studio

Do your paintings tell your story?

In reality, they are all my stories. For example, Impulse is a series about the ultimatum of female beauty. You see how I threw puddles of paint on those paintings; they are really violent attacks. Impulse is always an act of violence, but an act of violence is also an act of love. I´ve lived a lot of violence, I´ve seen a lot of female violence. For me, it´s also a way of dealing with this topic, and of letting it go. It´s not that I am trying, through my work, to better the world, but that I simply try to show the world that these aspects must be considered, must be seen, named and above all given a voice.

Everything about you is learning and overcoming.

That is what I always try for. Elena, in everything that is ugly, you have to find that spot of beauty. Because it´s there, it´s always there, in the most horrible things that happen to you. I always say: if you haven’t walked on the carpet of sorrows, you can´t kiss life. It´s important, so you can know what you love and what you don´t. Imagine getting to the end of life, at an old age, and regretting everything we haven´t done, because we didn´t want to get into trouble, we didn’t want to commit or suffer too much. Can you imagine that?

Courage, that great virtue.

Courage is an act of responsibility. It´s so important, it allows you to change things, to move forward. What frightens us most is to be responsible for our actions. If you are brave, it means you accept that things can go wrong. Do you know how beautiful it is to accept that things might go bad? That´s freedom. Courage is freedom.

Lita Cabellut and Elena Cué during the interview. Photo: Elena Cué

- Interview with Lita Cabellut - - Página principal: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

Jean-Luc Nancy (Bordeaux, 1940) is one of the foremost French thinkers of our time. For many years, he was Professor at the Université Marc Bloch in Strasbourg. His Christian background, present in his beginnings, evolved with his discovery of Heidegger’s philosophy. Another decisive influence was his discovery of Structuralism and his contact with Derrida, which among other things served to strengthen his preference for the contemporary in his philosophical reflections. We began by talking about the challenges that philosophers face nowadays. What would you say are the greatest challenges that philosophical thought faces today? In philosophy, nothing is a given. No meaning can be considered obvious.

Author: Elena Cué

Jean-Luc Nancy. Foto: Aïcha Messina

Jean-Luc Nancy (Bordeaux, 1940) is one of the foremost French thinkers of our time. For many years, he was Professor at the Université Marc Bloch in Strasbourg. His Christian background, present in his beginnings, evolved with his discovery of Heidegger’s philosophy. Another decisive influence was his discovery of Structuralism and his contact with Derrida, which among other things served to strengthen his preference for the contemporary in his philosophical reflections. We began by talking about the challenges that philosophers face nowadays.

What would you say are the greatest challenges that philosophical thought faces today?

In philosophy, nothing is a given. No meaning can be considered obvious. For example, it isn’t possible to talk about “man”, “society” or “science” as if these words designate well-identified realities. The challenge is precisely not to latch on to any acquired identity. For a philosopher, nothing should be taken for granted. Preconceived and established meanings must be constantly reevaluated, and new possibilities opened.

How can a philosopher teach a society to think this way when it is as anxious as ours is for answers and truths that it can cling to?

It is precisely this impatience that can be a trap. In one sense, impatience is right: there is no reason to wait, and the conditions for a decent life can be demanded at any time. On the other hand, there are obscure and complex questions to which emphatic or “radical” answers, as we like to say, can be dangerous. The recent Brexit is a good example: the vote has just taken place, and its supporters have already become nervous and begun to question it. Or Podemos, which started off very strong but has quickly lost strength instead of gaining it. Furthermore, the current complexity is the result of opposing “impatiences”: the one felt by those who are excluded and the impatience of those who fear exclusion (the middle class); the impatience of people seeking refuge and the impatience of those who fear being overrun by refugees; and the impatience of those who miss how things were in the past vis-à-vis those who want to accelerate the arrival of the future.

At present it’s much more difficult to set a course than it was at the time of the workers’ struggles or the end of dictatorships. How did Franco’s dictatorship last so long when many people were against it? Because it was a time of societal transformation and transformation of the European economies, and in turn these transformed the conditions that would prepare the end of the dictatorship. Why are the European Socialisms and Communisms in crisis? Because their motors are too old. We have to find new ways for a new state of affairs in which techniques, powers and expectations have transformed slowly. And in fact, this is what needs to be made understood: a patience that is active rather than passive. An impatient patience and a patient impatience.

You have written often about terrorism, especially after the grave attacks in France. What is your opinion on this subject?

This terrorism is the combined effect of two forces: that of the change in Western dominance and of the assertion of Islam, which has seen its equilibrium destroyed by colonization and the end of the Ottoman Empire. This terrorism reveals an extreme situation created by the very strong contradiction between the Western model of development and wellbeing, and the reality of existence in countries that feel marginalized, and where the upper classes or casts preserve the enormous differences in terms of wealth and status.

At the same time, the West is weak in its own strength. It doesn’t believe in its own civilization any more, it is preoccupied with its own technique and sees how capitalism grows without lessening differences in standards of living, while no Socialist economy has been able to last long (the Soviet economy was a State capitalism). In fact, there is no “West” anymore, and instead there are techno-economic poles of power whose visible heads are the United States of America and the Non-United States of Asia, but whose possessions and actions are found almost everywhere, and wherever there are resources to be exploited. Europe no longer has a consistency of its own, and it is subjected to this division of world powers.

And globalization...

Therefore globalization provokes explosions, tragedies and social and cultural collapses of all kinds. For five centuries we believed that utopias were achievable, and we have believed in their vanity. Now we have to think differently, and reflect on our place in the world. This will take a very long time… centuries, forcibly… But societies have always shown that they are able to overcome considerable challenges.

What are you referring to when you talk about the “surprise of liberty” Do you believe that we are free, or not?

Liberty is not a faculty we possess, or a right that we have at our disposal. Liberty resides in the fact that our existence is not programmed, and must find its own path. However, it has to do so as existence in a world that has conditions and limits. We are not free if that means “to be able to do what one wants” and “be independent of everything” because we depend on a lot of things, and most times our “will” consists only of propensities, hopes and yearnings that come from somewhere else. Understanding this and what that means is the beginning of liberation. And that is why liberty surprises us, because we discover that there is something other than what we thought was obvious.

For example: I become ill and cannot do my job, but I can see my state as an experience; the experience of not being in charge of all of my decisions, or of my preferences. Sometimes the ailing “give lessons” to those who are in good health.

Could you explain how suffering is an opportunity to broaden liberty?

That’s not what I am saying… and above all I’m not saying that it is an “opportunity”. Suffering is not a favorable occasion, it’s a reason to rebel, and especially to look for how to rebel, in the best of cases. In other words, to what end? Surely the aim is to not suffer more, but even that must be defined. For a long time, that goal was grounded in the word “Communism” or “Socialism”. But these concepts were never truly developed, except for in the Soviet form, and that form failed.

Why did it fail?

That analysis has not been done yet, or not sufficiently. Instead of looking deeper into that question, communists are happy to just deplore the dirty capitalism that has supplanted any idea of a fair society with that of consumer freedom. They complain about injustice, but they don´t know where justice is found. For example, we often hear talk today about a universal minimum wage. It seems like a fair and good idea, but it is also a very dangerous idea that would contribute to keeping many people at that minimum. The truth is that nowadays, in order to invent, first we must think. And we must scream as well. Brexit was an outcry by those who have been treated with contempt by the ruling class in Europe. We have to listen to that outcry. But what should we understand from it? That is what remains to be seen.

In your book The Deconstruction of Christianity, you talk about religion in today’s world. Could you tell me a bit more about that?

It isn´t about breaking, or annihilating, but about taking apart or de-structuring an edifice to show what it is made of. Now, Christianity is not made of religion. It was made from a profound mutation of Mediterranean humanity when it needed to emerge from the Ancient World, a world of limits, a finite world, and what we could even call de-finition. Everywhere there were gods with precise functions, rules to comply with, models to imitate and fixed horizons. At some point, that all crumbled. Undoubtedly, with the Roman Empire we saw the first “globalization” – when there was a departure from closed territories and fixed conditions (such as “free man vs. slave”). So then a desire for the infinite, and the promise of infinity began. This attainment produced a change in civilization, culture and society gave rise to the great adventures of the modern world, with all of their risks.

And with this deconstruction of Christianity, what specific conclusions have you come to?

The first conclusion is the most important: the profound transformation of the culture that occurred with the arrival of Christianity was the departure from religion as idolatry, as superstition, towards a cosmo-vision with an infinite horizon. The universal, the “whole” of Christian catholicity means, above all, the unlimited: no more idols, and instead an open infinity. So there is also energy for enterprise: we can and we must transform ourselves, and transform the world, infinitely. Christianity has materialized itself as humanism, as capitalism and as technical progress. This all becomes problematic and obscure, but we are always looking towards infinity. And religion as a collective point of reference has disappeared from the West.

The second conclusion is just the opposite: if Christianity took on the imposing religious form that it has had for centuries, it is because the certainties and references on which it is based are always desirable and highly desired. Then there are those who appropriate these references to construct meaning, as an instrument of power, an ideal of beauty or of the gratification of thought, and those who (and strangely, they are sometimes the same) seek representations, images and legends they can deliver themselves to. Atheism is unable to resolve many doubts. And that’s a shame, because religion as assurance is a lack of liberty, except for mystics and great spiritual men who have, on the other hand, helped many religions evolve as well.

To end, let’s talk about art. In what ways do you think that the meaning of “contemporary art” is different from traditional art?

Traditional art was linked to the possibility of the representation of truth – a religious, political or heroic truth, or a truth of perception, sensation or feeling. The modern world sees truth as an infinite process of searching. There aren´t stable and accessible figures or forms anymore, not even in what art has been able to produces in terms of forms we call abstract or colors without precise forms (Rothko, Newman, Pollock). A whole culture is being invented where the very meaning of “art” is becoming more obscure, precisely because it is no longer about representing given truths.

What would it mean?

The meaning of “art” is, in a way, necessarily enigmatic and elusive, because it does not allow itself to be formulated by language. Think about music: with twelve-tone music, serial music, electronica, jazz, rock and mixes of tonal and atonal music, our panorama of sound has changed considerably (as has our visual landscape, but sound has a stronger sensual penetration; think of electrification, techno, rap, slam, etc.). We look for new sensibilities, and that has its risks, of course. We search for what sensibilities and what enigmas of the senses are becoming “ours”.

Foto: Jean-Pierre Daumard

- Interview with Jean-Luc Nancy: The West is no more - - Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Cristina Ojea Calahorra

Whenever we come across a line, what we see might well be some kind of barrier or boundary dividing one space from one or more others. However, if we think beyond it as that enough to breach it, a whole world of possibilities opens up before us. When we walk the line, the boundaries disappear and another unexplored, unexpected path opens up. Walk The Line: drawing through in contemporary art is a stroll through a collection of artworks dedicated to the delineation of a segment, its texture and its trail. If a line indeed symbolizes the most primitive of artistic expressions, the suite of works exhibited here takes up that original remit: drawing as the essential principal of artwork.

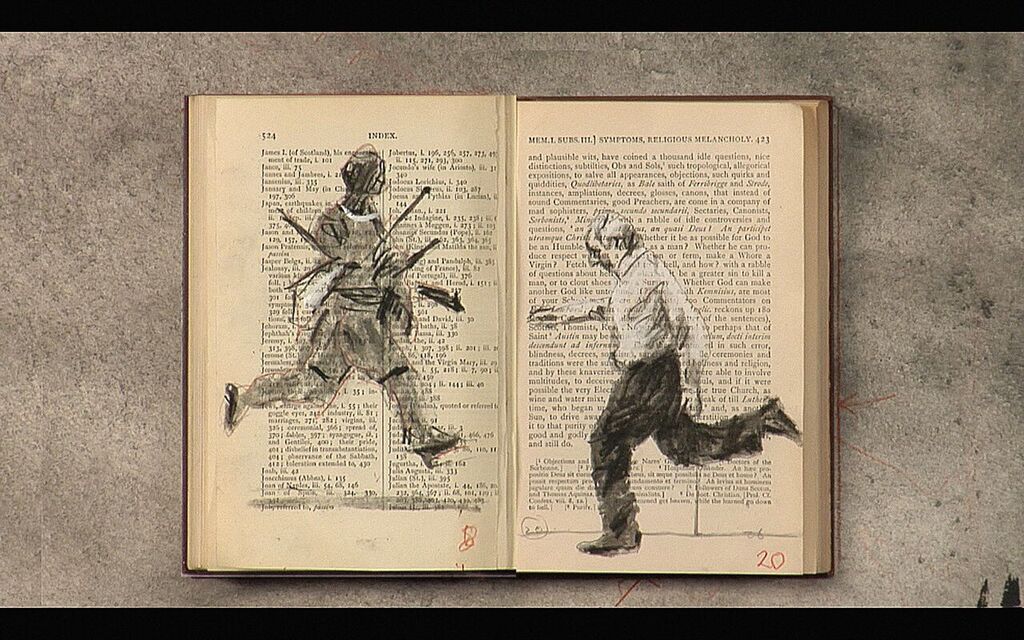

William Kentridge: Tango For Page Turning, 2012-2013. Single Chanel HD video. Picture courtesy of Galleria Lia Rumma Milan/Naples.

Irma Blank. Radical Writings, Vademecum VI, 1994. Ballpoint pen on paper. Courtesy of: Gregor Podnar, Berlin / P420, Bolonia.

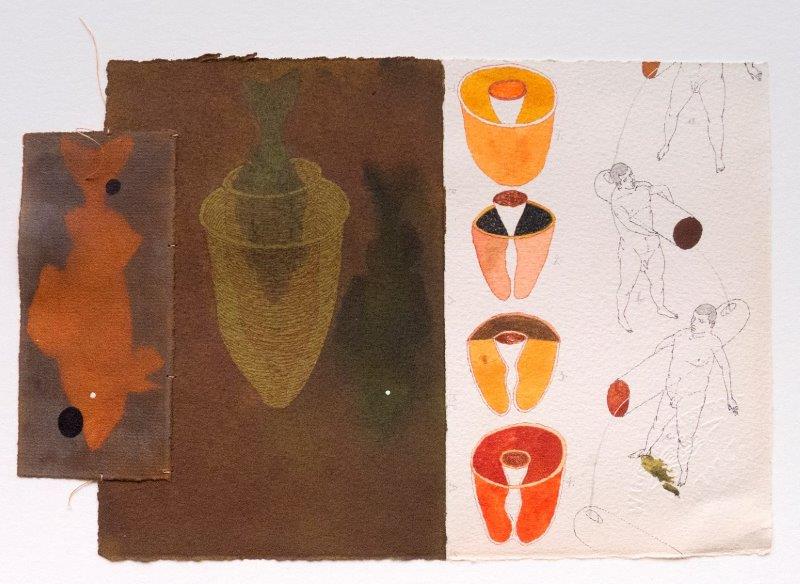

José Antonio Suárez Londoño. Untitled (1), 2015. Mixed media on paper. Courtesy of Bernal Espacio Gallery, Madrid.

{vimeo}153658531|600|350{/vimeo}

Galeria Bernal Espacio. 10 - 29 de February 2016.

(Translated from the Spanish by Shauna Devlin)

- A Question Of Dimension. Contemporary Drawing - - Homepage: Alejandra de Argos -

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

British artist Jenny Saville (1970), one of the Young British Artists, deconstructs the stereotypes of beauty and eroticism of the female body as seen through art and through men, and then broadens them. She experiments with obese women and changes in the body, but above all she uses her own body as a model and means of reflection. She reveals the natural beauty of the individuality of the women she paints, and her own. Through the body, she expresses states of sensibility that bind us to our existence: uneasy, anguished, painful fleshiness… This defines her artistic language as much as her traditional pictorial technique. Figures are the sole focus of attention of her huge canvasses, which often cannot contain the whole figure in the same way that our selves cannot control our bodies. Her painting and her skill at drawing spawn a multiplicity of realities that build movement.

Author: Elena Cué

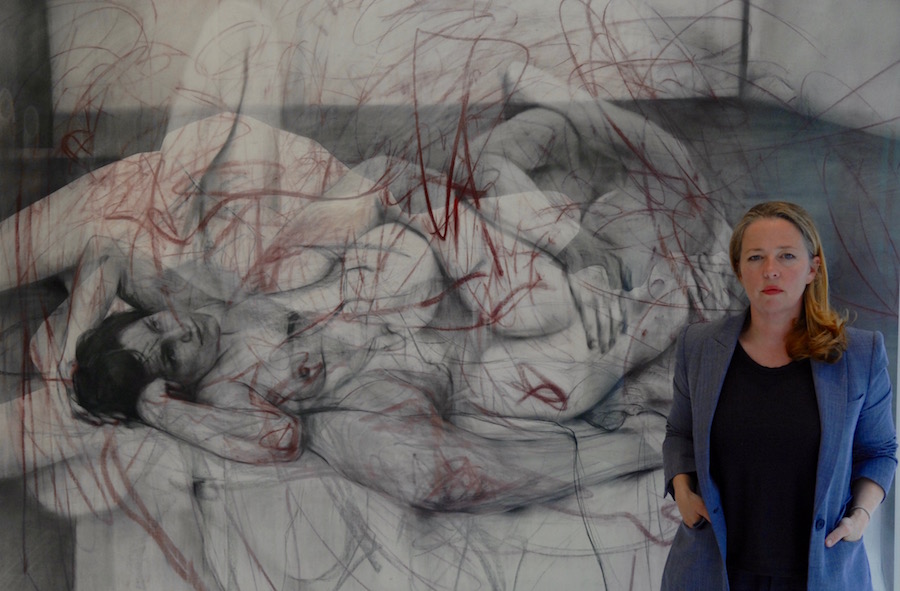

Jenny Saville. Photo: Elena Cué

British artist Jenny Saville (1970), one of the Young British Artists, deconstructs the stereotypes of beauty and eroticism of the female body as seen through art and through men, and then broadens them. She experiments with obese women and changes in the body, but above all she uses her own body as a model and means of reflection. She reveals the natural beauty of the individuality of the women she paints, and her own. Through the body, she expresses states of sensibility that bind us to our existence: uneasy, anguished, painful fleshiness… This defines her artistic language as much as her traditional pictorial technique. Figures are the sole focus of attention of her huge canvasses, which often cannot contain the whole figure in the same way that our selves cannot control our bodies. Her painting and her skill at drawing spawn a multiplicity of realities that build movement.

We begin our conversation in London surrounded by her latest drawings.

Your bodies experience anxiety, strangeness, sorrow... Do you recognize yourself in your multiple representations?

I think you are in everything that you make, to be honest. But I like to include everything, even to show sadness and violence. I want to encompass the whole world when I make art, I don’t want to exclude anything. The best work I’ve ever made has been through my instinct. When I try to be too clever or too analytical, it doesn’t work. I don’t ask myself too many questions during the making of the work because I follow my instinct. It holds a truth which is greater than the truth that I’m trying to get at through over-analyzing something. That was a lesson to me quite early on – that there’s something within that truth; that there are truths greater than knowledge. And if there’s a knowledge, sometimes you have to let go and follow your instinct to get to that greater truth. If you over-analyze or over-critique something, there’s almost no point in doing it. There’s no risk involved. I like the risk and the change and the transformation that’s possible in the making, and for me, that gets you to a greater art. It’s beyond reason. That’s what you’re trying to get… truth beyond reason. Because if you could write it down or you could speak about it, you wouldn’t need to make it.

Jenny Saville. Reverse, 2002 - 2003. Oil on canvas.© Jenny Saville. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian Gallery.

The figures in your drawings overlap as a plurality of identities. Your face is present in most of your portraits. Is identity an important subject for you?

It’s not really my identity… I lend my body to myself, that’s the way I’ve always looked at it. But sometimes people aren’t prepared to put themselves into as painful a position as my body is prepared to be in. I’ve been conscious - since I was very young - that one day I’m going to be under the ground, I’m going to be dust, I’m going to be nothing. So what’s the risk? There’s no real risk. What could it be? Judgment? That I have a different body? That I don’t have an ugly body? I don’t care about that. I care about trying to use my capacity as a human. How far can I go as a human to make something that’s interesting? It’s not really about whether it’s my identity or not. It’s about a human identity. If you look at the Velázquez dwarf paintings, there’s an identity that goes across all of humanity. Or a great Rembrandt portrait – it covers everybody. I’m not an old woman in a Rembrandt painting; I don’t know what it’s like to be a seventy year old woman, but I feel the humanity when I look at that painting, so that’s the way I’ve looked at it.

If my body can offer me the ability to get to something interesting, then I use my own body. If I can’t, then I work with somebody else. So it’s not about this endless self portrait, it’s just that I’m available and it’s the ability to use my body to say something or to get to the emotion that I’m trying to get at in the work.

Jenny Saville. Compass, 2013. Charcoal and pastel on paper on board. Photo: Steven Russell.

Where does your interest or fascination for imperfect, violated, wounded or operated on bodies come from?

I don’t really know. It’s something I’ve had since I was a child. If someone fell over, I wanted to see what had happened. It’s curiosity; I just have a curiosity for that. It’s also an aesthetic interest. I mean, I’m not so interested in a kind of surface beauty, I think there’s a certain humility to getting underneath the surface of something or being prepared to show the reality of something. There’s a humility involved in it that I find in the work that I like. If you look at ancient Greek theatre or Greek tragedy, and you’re harrowed by the emotions on stage and the extreme violence, somehow that gives you a humility in who you are as a human being in the face of gods, or in the face of the universe. You’re so small and nothing. I think that’s the drive, because that’s the kind of art I like across the board – whether it’s in film or music – it’s the art that touches that part of us.

You spoke earlier about the influence that clasical artists from the past have had on your work. There is also a carnal tradition on Western painting. What is your opinion on art from other eras?

I’ve naturally always looked at older art. Especially because if you paint the figure when you’re young and you’re trying to learn, you’re going to look at figurative painting. So I learned by looking at Titian, Velázquez, Rembrandt, Leonardo, Michelangelo… I was very lucky as I had an uncle who, from when I was eight, really taught me to look. Also, if you want to have a hero to look at, choose a really great artist, because that’s your measure. You can think that you’re great in the time that you live in, but you only have to look at really great artists and you’re a long way from that level. I’ve held that very dear to me, it’s become the backbone for the way that I work. However much I try, I’m never going to get to that. It’s a long journey to try and reach anything like that. And then I have had an interest that has switched or moved around… I mean, I have a team of players around me who I’m in constant dialogue with – artists like Picasso, Velázquez, Michelangelo, Leonardo, Titian, Tintoretto, Rubens – and then I have other art which is ancient Greek sculpture that I love, fertility goddesses from the ancient world, all of those. After I had children, I wanted to find an art that felt like the rawness of giving birth. I lived in Sicily for a long time, so being in Palermo around those myths and ancient history really linked me to that and the myths of the ancient Greek world… gods and goddesses and the power of fertility. So that seeped into my work a lot then and it’s a big driving force in my work now, especially in the drawings. A kind of creative urge. I’m much more interested in what the life force is of a creative urge, or how to make something and destroy it and bring it back. Through that cycle, which is basically a cycle of nature, you get to a greater truth, or a more interesting area of the work. I only really managed to do that through looking at ancient art.

Jenny Saville. Propped, 1992.© Jenny Saville. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian Gallery.

You also had a dialog, this time through an exhibition, with Egon Schiele at the Kunsthaus Zürich last year. What held the most significance to you from that experience?

The whole experience was an amazing journey. As a teenager, I absolutely loved his drawings… the honesty and the brutality of his drawings, of both himself and the females that he was drawing. My aesthetic interest led me to Egon Schiele at a very young age, so when I was asked to do a show together with his work, it was a dream. It was an incredible dialogue.

In that exhibition, the Schiele paintings were imbued with a strong eroticism. Is this also an important subject for you, do you think it is implied in your work?

It has become more and more important, I would say. Instead of erotic in a sexual sense, I would say erotic in a life force or drive. That’s really vital to my work, especially in the drawings, because of the way that I work now. It’s almost like a performance when I’m working, so I do sessions of working for four hours for example, where I draw lots of figures and they start to collapse and then I build them back up again. And through that whole physical process, like a game, new forms start to emerge from the nature of the drawing. So it is a sort of game where you get lost, and through it, you’re almost sculpting out a reality from the process of that moment. It’s almost like a dance or something; you create things that you didn’t know were in you.

Instead of one thing that represents what it is, when you multiply you get closer to a greater nature. That’s become very interesting for me and I’ve only really developed that in drawing because I can change so much and have several toes interlocking, or a male body over the top of a female body and that suddenly become a hermaphrodite. But I’m not drawing a hermaphrodite. I’m drawing many bodies together so that the gender becomes fluid. So parts of the male body become the female body, and that becomes really exciting because it almost represents more what we’re like as humans, rather than these separate sexes. We’re made up of masculinity and femininity, so those are the things that become interesting by layering them up.

Do you feel that you have a body or that you are a body?

Some artists like Michelangelo worked almost with God working through him; he was doing God’s work and there was a kind of divinity involved in it. God has been slipping away for most of us, but when we make work, I’m interested in what the drive is. When I’m working in the middle of the night and I’m trying to get to something, am I working with a wager on God’s existence? I don’t make work for an audience. I don’t make work thinking that I’m going to show this to an audience. But it’s definitely a form of communication. So it’s almost as though there is a third person involved, whether it’s God or whatever. That drives me to go further in the work, and I don’t know what that is.

Jenny Saville. Fulcrum, 1998 - 1999. Oil on canvas © Jenny Saville. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian Gallery.

Are you interested in the outside world?

Landscape is hugely interesting to me. Especially the sea… I spend hours looking at the water. I look at the way the light moves on the water. I get up early so that I can see the sun come up. But I don’t want to paint landscape paintings. I’m interested in all of those things. But I’ve never wanted to paint those directly, like I have with the body. And actually, the older that I get, the more closely related to nature I feel, or the more interested I am in depicting that. My mediation is through the body. All of my work really has been a sort of landscape; it’s the landscape of the body, or the architecture of the body in nature, or the nature of flesh, or the way that light affects a body.

What is art to you? What is your definition of art?

I would say the ability to have freedom. That’s fundamental. I really believe in imagination and inventiveness. It’s a combination of factors including humility, incredible hard work – it’s going to take a long time to have any kind of mastery in this – plus being brave enough to take a risk. When, in the work, if I’ve made something look really good and I sit back and think that it is looking good, that’s the moment that I try to destroy it, whereas before I’d polish it off. Now I’ll say well, that was easy access, or an easy journey to get there. Where else can you go? If you’re prepared to do it, you can get somewhere far greater. That takes a lot of hours and a lot of risk, but you’ve got nothing to lose. Why not try to invent something? I have learned through Picasso that the really good art lies in the ability of not knowing how to do something. And the journey of trying to articulate something you don’t know how to do is where the art is. If you know the journey that you’re walking, in a way there’s not much point in walking that journey. It’s in the struggle of trying to articulate something that almost seems impossible, but you’ve got a hint in your initiative to do it, or an instinct, and you follow it. That struggle to articulate it is really where you can find something interesting and Picasso is the artist I’ve found who can do that, so he’s really been a guide for me in the last few years.

- Details

- Written by Elena Cué

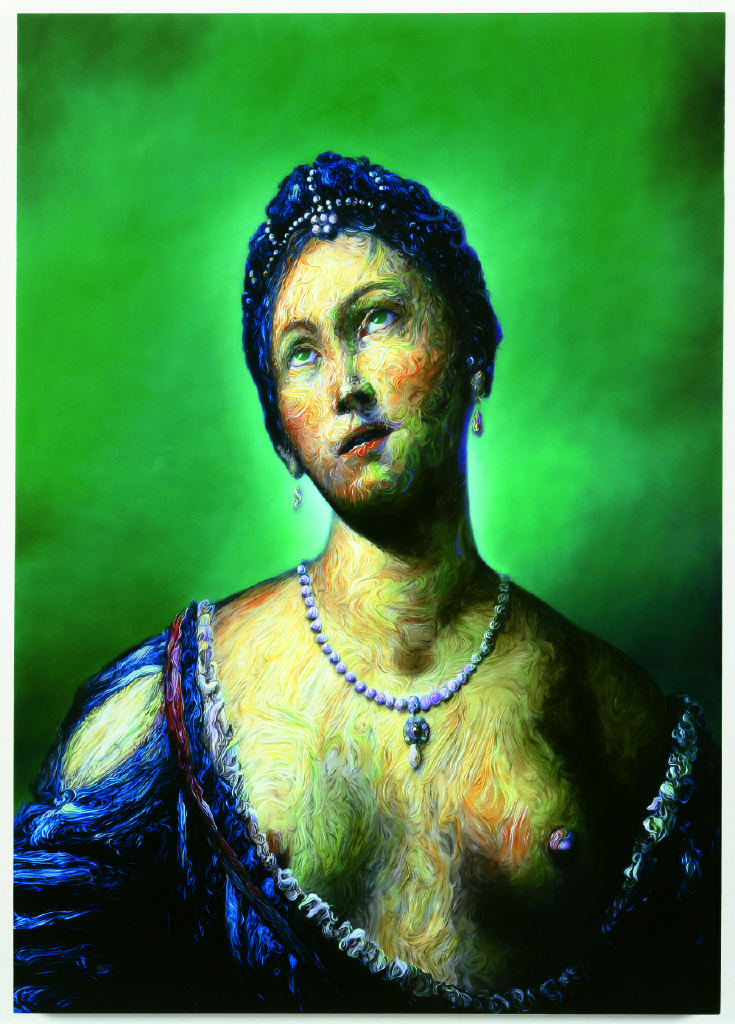

British artist Glenn Brown (1966) himself acknowledges and admits the influence that French Post-Structuralist philosophy has had on both his thought and his works. Too much knowledge when contemplating a work of art can prevent the viewer from seeing and experiencing the emotional content of it, but this is counterbalanced by the great stimulus it poses for the mind. At a time when it is claimed that painting is dead, artists like Glenn Brown prove that it is very much alive. He uses a technique that bestows movement to the essence of the subject portrayed. It is as if, by breaking free from classical linear form, he opens the floodgates of its essence, stripping it from its static state and transforming it into an evolving entity. He takes over iconic works of other artists and transforms them.

Author: Elena Cué

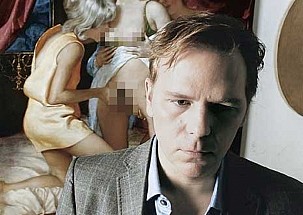

Glenn Brown. Foto: Elena Cué

British artist Glenn Brown (1966) himself acknowledges and admits the influence that French Post-Structuralist philosophy has had on both his thought and his works. Too much knowledge when contemplating a work of art can prevent the viewer from seeing and experiencing the emotional content of it, but this is counterbalanced by the great stimulus it poses for the mind. At a time when it is claimed that painting is dead, artists like Glenn Brown prove that it is very much alive. He uses a technique that bestows movement to the essence of the subject portrayed. It is as if, by breaking free from classical linear form, he opens the floodgates of its essence, stripping it from its static state and transforming it into an evolving entity. He takes over iconic works of other artists and transforms them. He disassembles his images and presents them in a new way. The interconnection and dialogue with artists of the past help develop his own style and render his own interpretation. Opposites, humor, kitsch, even the pleasure of destruction and the fascination for the decomposition of the human form are also characteristic features of this artist.

We begin our conversation surrounded by his paintings in his London studio, where sculptures inspired in the intensity of Van Gogh’s palette will travel to his upcoming exhibition in Arles.

Is the interconnection and dialogue with artists from the past a condition to building your own style and offering your own interpretation?

Obviously, it’s only a one-way reaction. I can only take from them; I can’t give back to them as would happen with artists when they come into the studio. So obviously, artists from the past can’t comment on my work, I can only comment on theirs. But yes, just in the same way that my work is a combination of myself and all of my friends and the people who have helped me make the work, it’s also the case that it is a combination of all the artists that I’ve seen and learned from. And to that extent, you go back to Gilles Deleuze in terms of any individual being made up of the parts of the society that has constructed them. We are part of a rhizome, a structure of society that develops the language with which we think, as if we’re made of language. We can’t exist outside of it.

Where identities are lost and one is with many other...

I’m just trying to make it very clear that all artists borrow from the past and we cannot be wholly original, because to step outside of originality is to step outside of language. To be wholly original would be to be nonsensical. I think the idea of the avant-garde has made people believe that an artist is supposed to return to some childish level of communication, where the inner-self can be expressed directly onto a canvas and the raw emotion that is beyond language and beyond society will come out in some way. Expressionist painting was supposed to be that. Hence why artists like Picasso and de Kooning to some extent were making these thick, grotesque gestural paintings mimicking the work of children, as if they had the real understanding of what it was to be human. I borrow some of their work, as if to say, well yes, you’re partially right that the work of children is raw and interesting and describes something fundamental, but really what you’re doing is a pretence - it’s a game, because you’re being a very sophisticated artist using sophisticated color combinations and nobody really believes that it’s the work of a child. You’re just pretending, like an actor pretending to be somebody. I’m sort of contradicting the idea of the avant-garde, or trying to, which I think is still very prevalent in our understanding of what art is. It’s too dominant in society. Too much importance is given to the understanding of the real, and not enough importance to the idea that there is a shared understanding of society and that we are social beings more than anything else.

Glenn Brown. Led Zeppelin, 2005. Oil on panel. 122 x 86 cm. Copyright Glenn Brown

Do you think then that style is produced by the forces from which thought springs?

To some extent, through my borrowing of artists as diverse as Gray or de Kooning or Rembrandt or Van Dyck, you could say I don’t know who I am myself, or that I have no particular style because I borrow so much from other people. I am partially saying that I don’t have an identity, I just choose.

Yet your work has its own distinct caracter that can immediately be attributed to you…

Precisely, because it is important as an artist, I think, to have an identity. Otherwise, nobody pays any attention. And although I’m saying it’s impossible to be original, I also believe that you have to try and be as original as possible and make objects that have never really existed before. So I am trying to make a painting that, although it’s based on somebody else’s work, you would never think was from the eighteenth or nineteenth century; it feels very twenty-first century and postmodern. I have particular styles of working, I mean the very flatness of the paintings and my obsession with the brush mark and the way that’s led into an obsession with the line and the movement that I try to create on the surface of the image, to make your eye slide around the image and continually feel that nothing is quite solid and everything is vaporous; sliding and moving and animated.

You said that you are not original and of course we are a combination of our pasts, but there is a tension between that and something in your thought process that can only ever be original.

That is the wonderful contradiction of making anything. You really want to present something and people like seeing new things; human beings are hardwired in their brains to want to see something new that they haven’t seen before. Something that is surprising and they can tell all their friends is different, and they now understand the world as being different to the way it was before. We love the idea of progression; that the human race is heading towards some nirvana where it becomes better all the time. I don’t believe that the world becomes better; I don’t believe that we become more intelligent. I just think things change - certainly in art. I can’t look at art from the Northern Renaissance – I’m thinking particularly of Dutch or German or Italian artists from the Renaissance. But I particularly like Northern European fifteenth and sixteenth century art. I really can’t think that art is better than it was four hundred years ago. I have Hendrick Goltzius’s etching over there of the Pietá, and I just can’t really conceive that art has ever got better than that, in depicting the idea of death and mortality and emotion and flesh and relationships and the way that the sky becomes electric with emotion. It almost predicts the idea of radiation in the work, or the idea that we are made up of atoms. There is something very atomized about that image.

You use a singular technique. With the movement that you imprint over the essence of the human being in your portraits, in order to break the linear way, do you intend for us to change our previous conception of understanding ourselves and the world?

The idea of the movement is that we are never fixed as individuals. Gilles Deleuze talks about the idea of the horse and the rider, and the rider, in understanding the horse, behaves like the horse. The horse behaves slightly like the human being because they both have to understand each other, in order for the rider to be able to ride the horse properly. They predict what each other are going to do, and are therefore joined together. There is a fluidity between the horse and the rider; between human beings and animals, just as there is when we have a conversation and we try to predict what the other person is going to say. Or we empathize with somebody else and that means there is a fluidity between one person and another. Brains almost literally become connected. That is why in a lot of the work, the linear form is trying to describe a literal fluidity - a melting, reforming or maybe rotting. The image decomposes, hence why I like painting flowers, because when they’re just at the point of being absolutely beautiful, they are about to die - cut flowers particularly, are already dead. They’re at the point in which they are at their most beautiful and we want to display them, but in order to display them, we have killed them. I love that contradiction of having to kill something in order to enjoy it. The important point is that the people and flowers and animals that I paint are maybe all appearing to be decomposing, but they are just transforming from one thing to another. The person rots away and then transforms into the soil, whose atoms then become part of the tree. Then an animal comes and eats the tree, and the tree becomes part of them. We all transform from one thing to another, we are all made of stars; the atoms that we’re made up of are billions of years old and once formed parts of stars. So it’s that idea that we are all eternal, to some extent. It doesn’t matter what form we take. We never truly die, we just transform continuously. I think that is also the essence of what it feels like to be human. I don’t feel as if I am absolutely aware of my skin the entire time, I’m not fully aware that I’m an isolated individual in the world. I feel like I’m part of the world, because I know what the street outside looks like and therefore part of my brain is out there in the street. I feel that I know what Russia is like, although I’ve never been there – so part of my brain is in Russia. I think to be human is to be fluid. It’s not to feel closed in. I’m trying to get at that idea of the inside and the outside, that the skin of the human being is translucent and things flow inside and outside. It’s as if the individual’s skin and flesh is turned inside out and we see the inner organs on the outside of somebody, or the musculature and the inner workings of the face all turned inside out, so that you start to see the structures that happen within the skin… I’m obsessed with that… the translucency of the flesh and the transmogrification of something turning from one thing into another. Andy Goldsworthy does that extremely well – the breaking down of one thing into another is done very beautifully, the way the line creates fluidity from one shape to another and then connects to each other. It is nothing original that I’m trying to do; artists have tried to do it for centuries.

Glenn Brown. Reproduction, 2014. Oil on panel. 135 x 101 cm. Copyright Glenn Brown

When you appropriate the paintings of other artists, what is your intent? To destruct and rebuild, or deconstruct and transform?

You do destroy, because it’s an act of homage to take somebody else’s work. People often ask whether I like the images that I work from, and I generally do, but not absolutely all the time. Sometimes they’re just paintings where the most important thing is what I can do to them, therefore I will see aspects of them without fundamentally necessarily needing to like the painting.

How do you choose?

It is something that I think I can transform. I see gaps in the work. It is a very disrespectful thing to do to another artist, to take their work and transform it, so it’s partially an act of homage and partially an act of destruction that I think I do. I’ve used a lot of the work of Frank Auerbach, and I like his work extremely, but I don’t think I could do what I do to his paintings if I wasn’t willing to say, well, I think maybe they don’t go far enough, I think maybe I can improve them… they don’t describe the world in the way I want it to be described, so it’s partially an act of criticism and partially an act of homage. I think it is like the relationship between the father and the son, or mother and daughter, where the two criticize each other immensely but they love each other. Families quarrel. Children want to rebel against their parents and tell their parents that they don’t know anything, that they misunderstand the world and that they know better. And all of those things are healthy, because fundamentally, we are our parents - they’re the biggest influence in our lives. So even though we rebel against them and hate them sometimes, they are us. It’s that same relationship of the parent and the offspring that I think I have with artists and art history. I love them and hate them in equal measure. To that end, when my father sees my work, he gets it immediately. He understands my work immediately. He’s my harshest critic, because he will sometimes see a painting of mine and say, you’re not trying hard enough with that one; you’re just trying to get away with it… you think you’ve done something that is good enough, but you can do better. He will point out bits that he doesn’t think works in them, and he is generally right as well. He knows the way my mind works. He is very helpful. It can be quite difficult sometimes, because he’s harsh… but good!

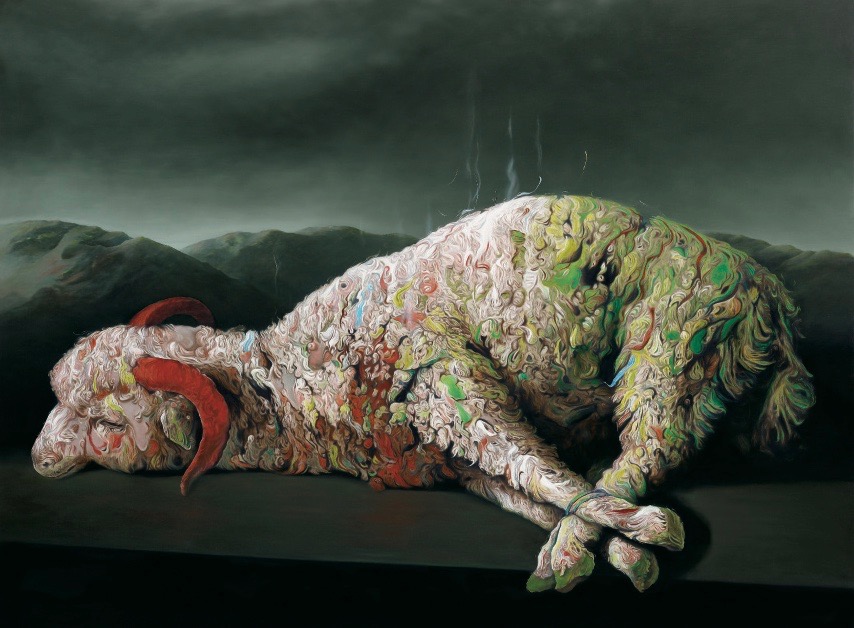

Opposites are very present in your work: figures between life and death, ugliness and beauty, opposite meanings of the paintings and their titles… Do opposites provide greater meaning?

They animate the painting. It is those strong emotions, when you see a film or you read a book and it takes you from a point of absolute elation to absolute disaster, and then back again to being elated. As human beings, we love to be told stories that make our heart beat faster and then calm us down. I don’t know fully why human beings like that; it gives us a sense of adventure, I suppose. I think as hunter-gatherers, we are hardwired to be interested in opposites because extremes can be very dangerous and we know we need to avoid them, very often. It all goes back to dreaming, as well. The reason we dream is to analyze all of the events that have happened in the previous day; to categorize them, to decide which are important and which we need to discard because it’s information we don’t need. It’s a sort of protection that goes back to hunter gathering. We want to know how the animal might behave, therefore we think, I need to think like an animal if I’m going to catch it. Again, going back to that fluidity of one thing flowing into another and the dream world being part of the actual world, and what differences there are between the two. You can’t really have a hierarchy; you can’t have the dream world without the real world.

Glenn Brown. Dark Star, 2003. Oil on panel. 100 x 75cm. Copyright Glenn Brown

The titles of your paintings are opposite to the meaning of the painting. What role does humor play in your work, so obviously present in the recycling of titles?

I like black humor… humor that is quite cruel. It appears to be nonsensical, but it’s about atomization basically, and it’s about the electricity between the couples. It is meant to be playing the game of having nothing to do with it, because there’s the idea of the human scale and the idea of the nuclear scale - which we perceive as either being very big or very small – with the human being in the middle. So there are opposites in scale within the idea of nuclear reaction. But it’s the electricity or the dynamism between the couples relating to the way they fight and argue with each other, yet love each other. And the way the marks are flying off, it’s as if the atoms are starting to break down and the radiation is destroying them. The idea of the destructive but creative power of radiation is in the work as well, because you don’t know whether the lines are flying off and breaking the figures apart, or whether everything is coalescing and forming back into itself again. There is a painting based on Zurbaran’s ram called Spearmint Rhino - it’s very big. Spearmint Rhino is a series of strip clubs, where women take their clothes off. And so you look at the picture of this ram, which appears to be decaying and smelling rather badly, wondering what this has to do with a lot of American strip clubs. And the ram is about entertainment. We have tied up the ram and killed it; it’s been sacrificed and killed for our entertainment. The reason we sacrifice things is illogical.

Glenn Brown. Spearmint Rhino, 2009. Oil on panel. 194 x 260.5 cm. Copyright Glenn Brown

What meaning do you give color?

I do generally take color from other artists. I will look at books by Kees van Dongen or Van Gogh or Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. But certain artists – especially those around the turn of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century – where they just tried their damndest to be as extreme as possible with color and really question what was possible, in terms of representing the world. And what happens if I make a painting where the sky is red, the trees are blue, the sea is purple and everything appears to be the exact opposite of what you’d expect it to be? But somehow by being the opposite, it doesn’t become unreal, it just becomes heightened reality, as if he is describing what is really there and we just haven’t seen it yet. I am just learning and stealing color from other artists, in order to try and heighten the theatricality of the real world. And not all of my paintings have very heightened color in them; for the last few years, I’ve been really concentrating on drawing, which has no color in it at all. Some of my paintings are black and white, where I’ll do the exact opposite, I’ll take all of the color out – or as much color as I possibly can – because even when you make a black and white painting, it’s never purely black and white. You get warm areas and cool areas. But I do like the way color describes emotion.

As a primarily figurative painter, how do you feel about the destruction of form, such as can be seen in your Auerbach-inspired paintings?

In a lot of the paintings, the original has become turned upside down, distorted and made abstract, in essence. You can’t recognize what I’ve painted anymore, though I have destroyed the original form and it’s been broken down into a surreal blob. There are a whole group of paintings that I call my blobby paintings, because they are not one thing. They appear to be renditions of a form, a blob, it’s at the point at which it could change into any one thing. You can’t really decide whether it is figurative or abstract, for instance, in a painting . But there are heads and figures you can see within it, so it’s at once both very figurative and very abstract as it transforms from one thing to the other. It has that fluidity of line, as though it is melting, or like chewing gum.

Glenn Brown. New Dawn Fades, 2000. Oil on panel. 71.5 x 62 cm. Copyright Glenn Brown

What stimulates you more, knowing the world or helping others think through your art?

I like that question. It brings to mind the idea of which is more interesting: experiencing something or reading about it, for instance. Like a lot of people, I would probably say that I like the experience of reading about something. I like the second-hand enjoyment. For instance, I like looking at paintings and portraits, because I like traveling the world through art, in many ways. Especially in the way that painting allows you to travel through time. You can go to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries through paintings, in such a fantastic way. Not just because they’re literal renditions of what it was like to live in those centuries, but also how people felt in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is different to how they feel now. Their ideas of beauty, their ideas of pain and what death meant to them was incredibly different. People were surrounded by death and therefore I probably find the enjoyment of somebody else’s description of something slightly more interesting than actually being there. To travel to China and to go to the Great Wall of China is nice, but to read about it is much more interesting. I can only really appreciate the world through the stories told about it.